Source: Link

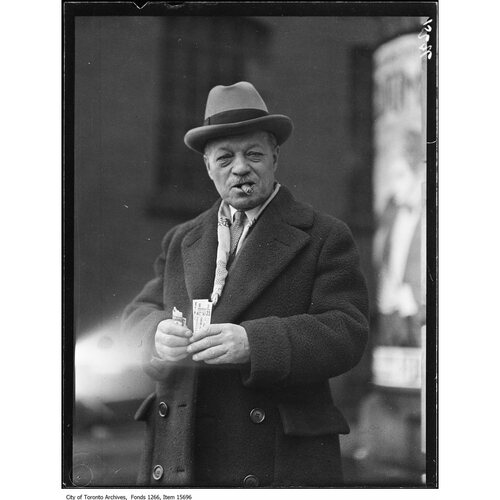

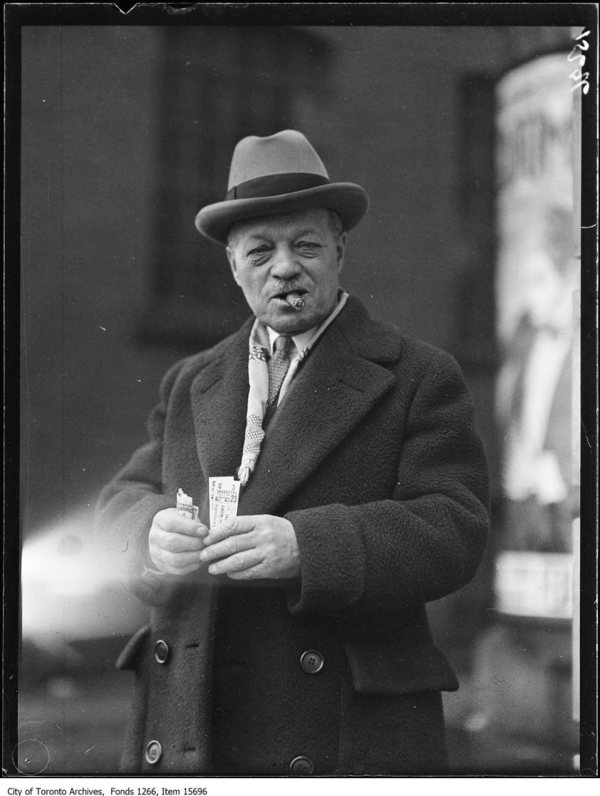

SOLMAN, LAWRENCE, businessman, sports and entertainment entrepreneur, theatre manager, and impresario; b. possibly 14 May 1863 in Toronto, son of Samuel Solman (Soloman) and Marian —; m. first Emily (Emma) Hanlan (1852–1917), widow of John Durnan; m. secondly 16 March 1929 Daisy Gertrude Walsh in New York; no children were born of either marriage; d. 24 March 1931 in Toronto and was buried there in Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

A shrewd, gregarious promoter who earned the nickname Toronto’s Weekend King, Lawrence Solman, known as Lol, was born to parents who hailed originally from London, England. His father, Samuel, was an optician and travelling salesman, and he and his wife, Marian, were active in Toronto’s Jewish community. After attending public schools and the local Mechanics’ Institute, Lol operated a mail-order business in Detroit before returning to his native city. There he started working for Edward Hanlan*, the world-champion oarsman, who owned a hotel at Hanlan’s Point on Toronto Island. By 1891 Solman had married Hanlan’s sister Emily Durnan, a widow with two children (one of whom was Edward John Durnan, who would also become an accomplished rower). The following year Ned Hanlan sold his hotel and Island lease to Edmund Boyd Osler*’s Toronto Ferry Company (TFC), which soon achieved a virtual monopoly on transport to the Island. The TFC enlarged the hotel, built an amusement park, and, in 1897, erected Hanlan’s Point Stadium on ten acres of landfill (later the site of Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport, named for flying ace William Avery Bishop*).

Although Solman is sometimes credited with being the owner and manager of the TFC during the 1890s, it is difficult to determine his position in the company before 26 March 1901, when the Toronto Daily Star reported that Solman (whom the paper describes as “present lessee of restaurant privileges on the Island”) and impresario Ambrose Joseph Small* had leased the TFC’s properties. “Mr. Solman will look after the ferry service and hotel,” the Star noted, “and Mr. Small will secure and manage the attractions.” Small’s involvement appears to have been fleeting, and Solman emerged as the sole manager of the company. He both invested his own profits and secured other backers, and he was always close to day-to-day management, an approach he would take in his future ventures. He ran the TFC until 1926, when it was purchased by the city, a controversial decision (the price was $337,500, of which $120,448.98 went directly to Solman).

To boost his business, Solman took a prominent role in the operation of the Toronto Maple Leafs Baseball Club and the Tecumseh Lacrosse Club; both teams played at the stadium. At the time, professional sports were frowned upon by amateur-sports enthusiasts such as Globe journalist Francis Joseph Nelson, but the Maple Leafs proved popular and helped make the integrated operations at Hanlan’s Point a roaring success: in 1902, for example, 174 baseball games were played in the stadium, as were 68 cricket matches, 38 football games, and 5 lacrosse matches; 192 group picnics were also enjoyed that year on the TFC’s premises. Lol was such a ceaseless promoter that when the stadium burned down in 1903, he ran extra ferries so gawkers could get a closer view of the blaze. The facility would be rebuilt in 1908 and again, after another fire, in 1910. It was there, on 5 Sept. 1914, that the legendary American baseball player Babe Ruth hit his first home run as a professional.

Having secured the lease of the TFC’s properties, Solman branched out to find other opportunities. In 1905 he helped form a syndicate (the other members were businessman Cawthra Mulock*, broker Robert Alexander Smith, and manufacturer Stephen Haas) that built the Royal Alexandra Theatre. The 1,497-seat venue, designed by John MacIntosh Lyle* and opened in 1907, quickly became regarded as the most actor-friendly space in North America, according to Paul Thompson, director general of the National Theatre School of Canada from 1987 to 1991. The Royal Alex’s first production, the musical The top o’ th’ world, included nearly 100 performers and 6 collies. Solman, the general manager, brought in many hits from New York and London; the 1907–8 season, for example, featured 45 productions staged over 44 weeks. He carefully kept the Royal Alex independent of Klaw and Erlanger, the American syndicate that was trying to monopolize the North American theatre scene. When live performances were later challenged by motion pictures, Solman eventually gave in to the financial realities of the Great Depression and became a vice-president of the Canadian operation of Loew’s Theatres.

Solman was part of the group that built the first artificial-ice rink in Ontario, the Arena Gardens, which opened in 1912 and had a capacity of 7,000 spectators. As managing director, he put on week-long opening ceremonies that featured performances by stars from all over North America, including actress Marie Dressler [Leila Maria Koerber]. According to the Star, Solman made the Gardens a “sporting cathedral” that featured the best amateur and professional athletic events. The Stanley Cup, donated in 1892 by Governor General Lord Stanley*, was won by the Toronto Hockey Club (also known as the Blueshirts), the first team in the city to capture the trophy, in 1914. Three years later Solman obtained the franchise, which won the Stanley Cup in 1918 as the Toronto Arenas; it was renamed the Toronto St Patricks in 1919 and then became the Maple Leafs in 1927. The team would continue to play at Solman’s rink until Maple Leaf Gardens opened four years later.

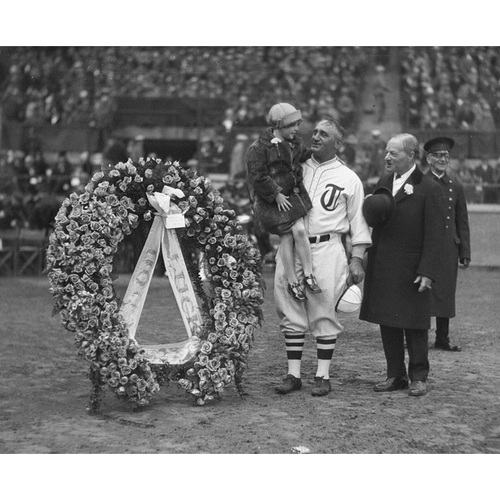

In 1916 Solman had been part of a group that pushed the Toronto Harbour Commission to complete the redevelopment of the beaches in the city’s west end, and in 1922 the Sunnyside Amusement Park opened for business. The rides, games, and hot-dog stands were run by the Sunnyside Amusement Company, of which Lol’s brother Saul (usually called Sol) was president; Lol, one of the directors, was the principal shareholder, owning $416,000 in paid-up common stock. He also purchased land for other purposes. Baseball remained his great love, and in the same year he became president of the Maple Leafs Baseball Club. Recognizing that the advent of the automobile had made travelling to the island less attractive to patrons, he decided to build a stadium on the mainland. His first choice was a spot immediately south of Union Station, but after Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario chairman Sir Adam Beck* objected because he wanted to put a railway link through the site, Solman accepted a location farther west, at the foot of Bathurst Street. Such was his reputation as an entrepreneur that the Toronto Harbour Commission, which owned the land, offered to build the facility in exchange for a guaranteed annual payment and a promise that Solman would serve as manager for one dollar per year. In the end he erected and operated the 20,000-seat Maple Leaf Stadium, completed in 1926, himself. American baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis felt that Solman Park would be a more fitting name, but Solman, with typical modesty, declined his suggestion. The team capped its opening season in the venue by winning the championship.

In addition to being a prominent businessman, Lol Solman became well known in the city as a benefactor to sick children, to whom he regularly gave free ferry rides to the Island, and to TFC employees, whom he hired in the winter to work at a restaurant that lost him money but provided them with year-round earnings. After he died of acute mediastinitis complicated by pneumonia on 24 March 1931, Solman was honoured with one of the largest funerals in the history of Toronto, held at St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, diagonally across from the Royal Alex. (Although his parents were Jewish, his first wife had belonged to a Presbyterian family, and his second marriage was held in a Presbyterian church.) Solman was remembered as a generous philanthropist, a devoted and unpretentious employer, and a father of professional sport and theatre in Toronto. By developing and operating so many of the major performance venues, professional teams, and amusement parks in the city, he had transformed its popular culture. A Star journalist who knew him well, probably Lewis Edwin (Lou) Marsh, noted in an obituary, “Above all things, he loved a great crowd.” Solman was a genius in attracting spectators to his events, and by doing so he helped bring respectability to professional sports in the staid city and encouraged Torontonians to value their waterfront.

The author would like to thank Paul Thompson for providing information about the Royal Alexandra Theatre in an interview on 8 Jan. 2013, and Jeff Hubbell and Victor Russell of the Toronto Port Authority Archives for their assistance.

City of Toronto Arch., Fonds 200, ser.430, subser.1, file 93 (Toronto Ferry Company); Fonds 1047, ser.1822, file 518 (Solman, Lawrence (Lol)). Toronto Port Authority Arch., RG 17/1, box 1, 199211180003, and box 4, 19921123006. Daily Mail and Empire, 25 March 1931. Globe, 25, 26 March 1931. Toronto Daily Star, 26 March 1901, 24 March 1931. Robert Brockhouse, The Royal Alexandra Theatre: a celebration of 100 years (Toronto, 2007). Louis Cauz, Baseball’s back in town (Toronto, [1977?]). Sally Gibson, More than an island: a history of the Toronto Island (Toronto, 1984). James Lemon, Toronto since 1918: an illustrated history (Toronto and Ottawa, 1985). Kevin Plummer, “Historicist: the unknown impresario”: http://web.archive.org/web/20161113045107/http:/torontoist.com/2013/09/historicist-the-unknown-impresario (archived copy, consulted 9 March 2021). [Toronto Harbour Commission, Public Affairs Dept.], Toronto Harbour, the passing years ([Toronto, 1985]).

Cite This Article

Bruce Kidd, “SOLMAN, LAWRENCE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/solman_lawrence_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/solman_lawrence_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Bruce Kidd |

| Title of Article: | SOLMAN, LAWRENCE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2021 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |