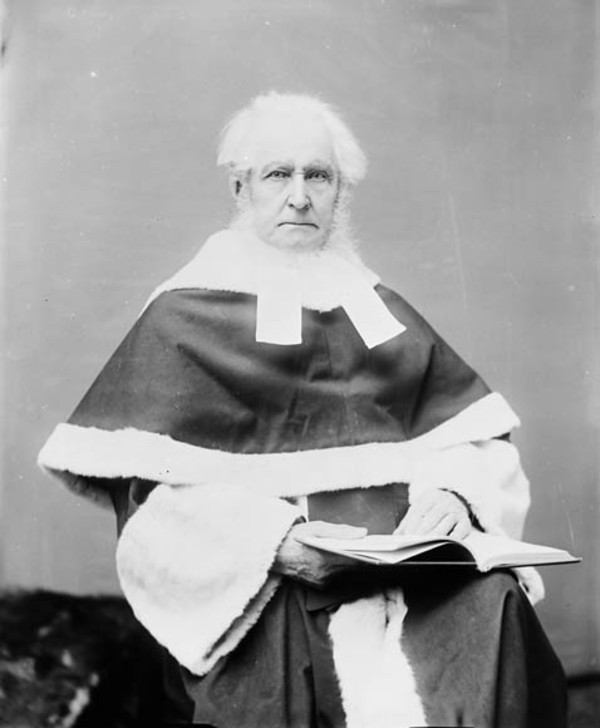

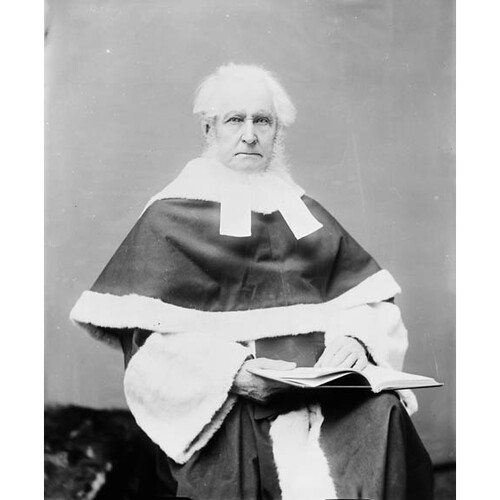

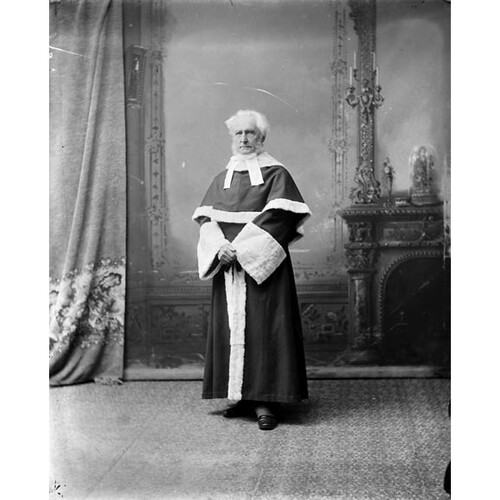

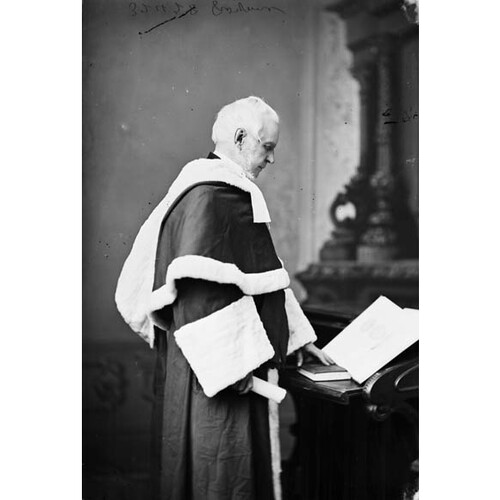

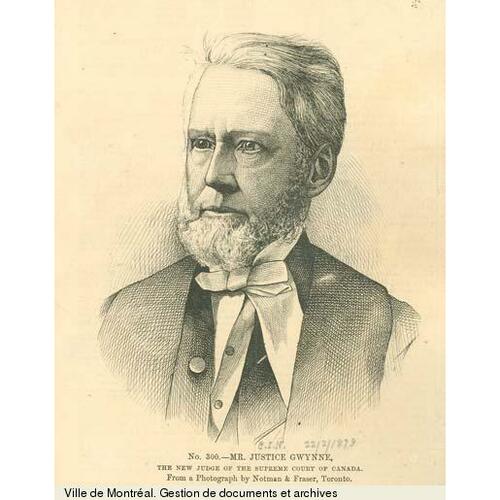

GWYNNE, JOHN WELLINGTON, lawyer, railway promoter, and judge; b. 30 March 1814 in Castleknock (Republic of Ireland), son of the Reverend William Gwynne and Eliza Nelson; m. 14 July 1852 Julia Durie, and they had a son and four daughters; d. 7 Jan. 1902 in Ottawa.

John Wellington Gwynne came from a family of 14 children, 8 of whom lived to maturity. He entered Trinity College, Dublin, in July 1828, but left without taking a degree. With an elder brother, William Charles*, he sailed for the Canadas early in 1832. He took the preliminary examination of the Law Society of Upper Canada in June 1832 and spent two years under articles to Thomas Kirkpatrick* of Kingston. In 1834 he moved to Toronto to complete his articles in the office of Christopher Alexander Hagerman* and William Henry Draper*. After his call to the bar in 1837, his career benefited from his social as well as his professional connections. His brother William had married a granddaughter of William Dummer Powell*, a former chief justice of Upper Canada; John became legal adviser to the Powell family and their relations, the Jarvises. Samuel Peters Jarvis*, chief superintendent of Indian affairs, employed him on departmental business; John Powell, judge of the Home District, appointed him his deputy during an illness in 1842.

In April 1844 Gwynne went to England to study in the chambers of John Rolt, a rising equity practitioner. His sojourn in London coincided with the great British railway boom. He and a friend launched a company in April 1845 to build a line from Toronto to Goderich, on Lake Huron, and interested several capitalists in the project. Named the company’s counsel and solicitor in Canada (though he remained in England), Gwynne undertook to seek the cooperation of certain prominent Upper Canadians, most of whom had been his associates in the Canada Emigration Association, an abortive scheme floated in 1840. On writing to one of them, William Botsford Jarvis*, he learned that the City of Toronto and Lake Huron Rail Road Company, which had been chartered in 1837 but had lapsed, had been revived. The new company offered to cooperate with Gwynne and his associates, but on terms which Gwynne condemned as unacceptable to British investors.

Gwynne’s group was already courting the Canada Company, which owned the harbour at Goderich and a vast tract of land along the projected railway [see Thomas Mercer Jones*]. The Canada Company’s president, Charles Franks, exploited Gwynne’s difficulties with the Toronto firm in order to take over his project. Gwynne remained active in the enterprise, but when the Toronto group sent one of the Canada Company’s commissioners, Frederick Widder*, to London to treat with the English company, Gwynne lost his standing as the project’s Canadian adviser. The Englishmen refused to compensate him for his services or for the losses he claimed to have incurred by prolonging his stay in London in order to promote the enterprise.

When Gwynne left England for Canada in December 1845, the railway boom had collapsed, draining the London money market and stranding the Toronto railway project. Since the Toronto company had committed itself to a terminus at Port Sarnia (Sarnia) rather than Goderich, Gwynne floated a new company to build to Goderich and proposed that the project be subsidized by the provincial government in consideration of the gains to be realized by the opening of crown lands north of the projected route. He linked imperial to domestic necessities, arguing that immigration from famine-struck Ireland would provide labour for the railway, which, when completed, would aid the immigrants’ settlement on the land. In April 1847 he took part in the founding of the Emigrant Settlement Society, which was set up to assist and direct the expected influx.

After securing a charter for the Toronto and Goderich Railway Company in 1847, Gwynne publicized the project incessantly. The government declined to subsidize the railway, but in 1851 it was refloated as the Toronto and Guelph Railway. Gwynne cooperated with the mayor of Toronto, John George Bowes*, to procure first the charter and then, in 1852, statutory authority to extend the line to Port Sarnia. Rival interests thwarted the company’s bid to build to Goderich. Following their marriage that year, Gwynne and his wife honeymooned in Britain, where he sought the Canada Company’s cooperation in marketing the railway’s securities. He also promoted the railway’s absorption into the Grand Trunk in 1853. However, the success of his second railway enterprise left Gwynne more embittered than the failure of his first, and for the same reason: the company that took over his initial flotation denied his financial claims. He did get some recompense from the Toronto and Guelph, but the Grand Trunk refused to pay him anything.

Gwynne’s passion for railways was at least partly responsible for his sole venture into party politics. In the mid 1840s William Charles Gwynne was attacking the predominance of Toronto’s tory élite in medical and university politics. John’s shabby treatment at the hands of the Toronto and Lake Huron and its London counterpart reinforced the brothers’ commitment to Robert Baldwin*’s reform party. In May 1847, in a letter to William that was clearly intended for the reform leader’s eyes, John declared his support for Baldwin’s view of responsible government but confessed his opposition to the idea of converting the clergy reserves into a fund for the support of general education. In December he stood against a cabinet minister, William Cayley*, in the traditionally tory riding of Huron, the chief town of which was Goderich. George Brown* expressed optimism about Gwynne’s chances in private as well as in the Globe, but Cayley won. Although the reformers thought of contesting the return, Gwynne was worried about the expense of such a challenge and the loss of income that attendance at the legislature would entail should he be elected. The return was allowed to stand.

Gwynne was elected a bencher of the Law Society of Upper Canada in 1849 and appointed qc the following year. During the 1850s he established himself as one of Upper Canada’s leading barristers, appearing in several causes célèbres. In Toronto v. Bowes (1853–56) he and George Skeffington Connor* defended J. G. Bowes, Gwynne’s railway companion, in the litigation arising from the scandal known as the “£10,000 job”; in Macdonell v. Macdonald (1858) he prosecuted his old friend John A. Macdonald* and other government ministers for their part in the controversial “double shuffle” manœuvre [see William Henry Draper]. In 1865, as crown counsel at the County of York spring assizes, he took part in the government’s efforts to prosecute certain of the St Albans “raiders” [see Charles-Joseph Coursol*]. It is not certain that, as stated in an obituary, he was ever solicitor to the Great Western Railway, but about 1857 he was briefly in partnership with Æmilius Irving*, solicitor to the railway from 1855 to 1872. He frequently appeared in court for the Great Western about that time, and, as a specialist in railway litigation, was retained by Isaac Buchanan* to advise him in the “southern railway” imbroglio. By the 1860s Gwynne had good reason to think of himself as a leading candidate for the higher judiciary, but that honour eluded him. His disappointment poured forth in a letter of 1864 to Buchanan, an mla, who had recommended him for the vice-chancellorship of the Court of Chancery to which Oliver Mowat had been appointed. Judicial preferment was reserved for politicians, wrote Gwynne; his seven years of public service as a railway promoter counted for nothing. “Responsible Government deals hardly with some of her votaries. I at least feel that my prospects would have been better under the old regime.”

In 1868, when W. H. Draper retired as chief justice of Upper Canada, Gwynne was his first choice for appointment either to the Court of Chancery or to the common-law courts. “I really think Gwynne would make a good Judge notwithstanding he is at times crochetty,” he wrote to John A. Macdonald, now prime minister. “I would as readily make him Chief Justice as Chancellor.” Macdonald’s wish to make Edward Blake* chancellor nearly inflicted another disappointment on Gwynne, but in the end it was a common-law post that had to be filled. On 12 Nov. 1868 Gwynne was appointed a puisne justice of the Court of Common Pleas.

In 1869 Macdonald could still call Gwynne a Reformer. This perception is surprising. Despite Gwynne’s identification with Baldwin’s reformers in the 1840s, his law partnership in the 1850s with Reformer Irving, and the Globe’s support for his railway schemes, it is doubtful whether he ever adhered to the Reform party under George Brown. His views on the clergy reserves were wholly at odds with Brown’s, and he must have resented the Globe’s hostility towards his friend, client, and fellow-countryman Bowes over the “£10,000 job”; Gwynne valued friendship as highly as railways. At the provincial election of 1854 he plumped for Bowes in Toronto, voiding his second vote, although most of the city’s mercantile and professional voters spurned Bowes on account of the scandal. Gwynne had probably known Macdonald since his Kingston days, and both men were friendly with judge James Robert Gowan, proprietor of the Upper Canada Law Journal, who was to be one of Macdonald’s private advisers in his constitutional conflict with Mowat after confederation. During the years 1872–74, several events reflected and reinforced Gwynne’s alignment with these Conservative friends.

In 1871 John Sandfield Macdonald*’s provincial government had appointed a commission of inquiry into the fusion of common law and equity. Its main work was done by Gowan and Gwynne, the latter becoming chairman in July 1872 on the resignation of Adam Wilson*. Fusion was a controversial topic within the legal profession because the majority of the provincial bar, especially outside Toronto, were common lawyers, equity practitioners being a Toronto-based élite. Gowan and Gwynne prepared a draft bill, which included a code of procedure based on the common law, since this was more convenient to most of the bar, but their labours were thwarted in September when the administration of Edward Blake revoked the commission. Blake and his attorney general, Adam Crooks*, were both equity practitioners. Despite the revocation, Gwynne had the draft bill printed and presented it to Mowat, who had become premier and attorney general, as the end product of the commission’s labours, but Mowat suppressed the bill.

In 1874 Gwynne was offended once more when the federal Liberal government of Alexander Mackenzie* appointed him a puisne justice of the Ontario Court of Appeal, newly reconstituted by Mowat’s government. The appointment was technically a promotion, since the puisne justices were to be of equal rank with the chief justices of the courts below. The constituting act also provided, however, that the judges should rank in order of their appointment, and the order in council appointing Samuel Henry Strong was not only dated the day before Gwynne’s but specified (though the statute did not require this) that he was to be “senior Justice.” Strong had been Gwynne’s junior, having been appointed vice-chancellor in 1869; he was also notoriously ill-tempered and had quarrelled with Gwynne during their membership on the fusion commission. Gwynne therefore rejected his appointment, preferring to remain in common pleas. Adam Wilson, a fellow judge, denounced Strong’s elevation as “unwarrantable and unconstitutional . . . a marked and most offensive proceeding,” and declared that Gwynne had had no choice but to forgo his promotion.

Gwynne’s anger at these personal affronts was pale compared with his fury over Macdonald’s defeat in 1873 as a result of the Pacific Scandal. “I cannot tell you how my blood boils at the very notion of our great Pacific Railway being lost to us,” he wrote to Gowan. “I feel as if, sadly maimed and wounded and crippled as I was for life by the cruel hands of those whom most I served, in my early railway conflicts, I could put on my armour again and enter the lists to fight for Canadian railway progress.” He denounced the Liberals for hypocrisy and a treasonous sacrifice of “all our hopes of nationality” and “our iron zone.” Alluding to Mowat’s recent resignation from the bench in order to assume the premiership of Ontario, he declared it would be an honour to be “permitted to renew the spectacle of a Judge descending from the Bench to assume the office not of a first but of the last minister of the crown – I mean the Doomsman or Headsman or Hangman.”

On 14 Jan. 1879, soon after Macdonald’s return to power, Gwynne was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada. Macdonald was almost certainly aware of Gwynne’s idea of confederation; if not, he must have gathered it from Gwynne’s outspokenly centralist judgement in the Niagara election case of November 1878. (The case concerned the validity of the Dominion Controverted Elections Act of 1874, which had transferred the adjudication of controverted federal elections from the House of Commons to the courts.) In an obiter dictum on the nature of the Canadian constitution, Gwynne proclaimed his belief in the dominion’s superiority to the provinces and in its possession of correspondingly ample legislative powers. Between November 1879 and June 1880 he elaborated this construction in three judgements which revealed him as the most committed centralist on the Supreme Court, Henri-Elzéar Taschereau* alone approaching him in this respect. In Lenoir v. Ritchie and The City of Fredericton v. the Queen, the court joined him in rejecting Mowat’s idea of the extent of provincial rights under the British North America Act; in Citizens’ Insurance Co. v. Parsons, it gave Mowat a majority decision. Calling Citizens’ Insurance “the thin end of the wedge to bring about Provincial Sovereignty which I believe Mr. Mowat is labouring to do,” Gwynne advised Macdonald, speaking for Taschereau and himself, to consider intervening if necessary to have the decision appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

Citizens’ Insurance was appealed, but the JCPC gave the first of a series of decisions which progressively established Mowat’s view of the BNA Act. These rulings were a rebuff to Gwynne in particular. That in Citizens’ Insurance was palpably influenced by a brief which Mowat had submitted in rebuttal of Gwynne’s views, and the JCPC’s construction of the final clause of section 91 of the act, both there and in the prohibition reference appeal of 1896, seems to have been made in correction of Gwynne’s. For his part, in 1889 Gwynne had called the Privy Council “the dispensers of the Prerogative . . . of dispensing with the BNA Act”; “Old as I am,” he told Gowan, “I fully expect that both you and I shall be present as mourners at the funeral of Confederation cruelly murdered in the house of its friends.” His last important statement on the subject was his judgement of 1895 in the prohibition reference, wherein he rehearsed all the arguments for provincial subordination to the dominion and especially for the broad definition of the federal power to regulate trade and commerce established by Fredericton. “If ever it should be reversed,” he said of that decision, “it will in my opinion be a matter of deep regret, as defeating the plain intent of the framers of our constitution and imperilling the success of the scheme of confederation.”

Gwynne’s life in Ottawa was marred by his separation from old friends in Toronto and by his continuing feud with Strong, a Supreme Court justice since 1875. In 1885 he confided to Gowan his wish to return to Toronto as a chief justice (provincial chief justices were paid as highly as the puisne justices of the Supreme Court), or even as a justice of appeal if he could retain his higher salary. After Strong’s promotion to chief justice in 1892, Gwynne’s refusal to attend judicial conferences induced Strong (calling the kettle black) to complain of his “extreme senile irritability.” From 1894 on the government occasionally contemplated forcing Gwynne to retire. He was willing to do so on full salary, but successive administrations declined to meet this condition. He last sat in court in November 1901 and died two months later.

Gwynne was a warm friend and a loving paterfamilias, mild of manner though uncompromising in the defence of principle. In religion he was a member of the Church of England. His historical importance lies chiefly in his vision of railways as instruments of national aggrandizement and in the coherence of that vision with his later role as the foremost judicial exponent of Macdonald’s centralist concept of confederation. To this view he was true to the end: the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council described his last important judgement, his dissent in Ontario Mining Company v. Seybold (1901), as an attempt to show that its decision in favour of Ontario in St. Catharines Milling and Lumber Co. v. the Queen (1888) was erroneous.

AO, F 129; RG 4-32, 1873, file C1721; RG 22, ser.225, 3: f.131; ser.354, no.3897. MTRL, City of Toronto and Lake Huron Rail Road Company papers; also a separate collection of City of Toronto and Lake Huron Rail Road Company papers within the William Allan papers. NA, MG 24, D16; MG 26, A; MG 27, I, E 17; RG 2, P.C. 626, 27 May 1874; P.C. 635, 28 May 1874; P.C. 735, 6 June 1874; RG 13, A2, 13, nos.509–12; 1868, file 1639/1874; B1, 797. Globe, 9 Dec. 1846–2 Aug. 1854. P. A. Baskerville, “The boardroom and beyond: aspects of the Upper Canadian railroad community” (phd thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, Ont., 1973). Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1885, no.85. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. Dent, Canadian portrait gallery. National encyclopedia of Canadian biog. (Middleton and Downs). Ont., Legislature, Sessional papers, 1873, no.26. Paul Romney, “From railway construction to constitutional construction: John Wellington Gwynne’s national dream,” Manitoba Law Journal (Winnipeg), 20 (1991): 91–106; “The nature and scope of provincial autonomy: Oliver Mowat, the Quebec resolutions, and the construction of the British North America Act,” Canadian Journal of Political Science (Ottawa), 25 (1992): 1–28; “‘The ten thousand pound job’: political corruption, equitable jurisdiction, and the public interest in Canada, 1852–6,” Essays in Canadian law (Flaherty et al.), 2: 143–99. SCR, vols.3–32. Snell and Vaughan, Supreme Court of Canada. Upper Canada Common Pleas Reports (Toronto), 19 (1868)–29 (1878).

Cite This Article

Paul Romney, “GWYNNE, JOHN WELLINGTON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gwynne_john_wellington_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gwynne_john_wellington_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Paul Romney |

| Title of Article: | GWYNNE, JOHN WELLINGTON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |