Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

DRAPER, WILLIAM HENRY, politician, lawyer, and judge; b. 11 March 1801 near London, Eng., son of the Reverend Henry Draper and Mary Louisa Oliver; m. 1826 Augusta White in York (Toronto), Upper Canada; d. 3 Nov. 1877 at Yorkville (Toronto), Ont.

Educated by private tuition, William Henry Draper ran away to sea at age 15. He made at least two voyages to India with the East India Company and in the spring of 1820 emigrated to Upper Canada. Settling in Hamilton Township, he lived with John Covert*, a prominent Orangeman of the Cobourg area. He appears to have intended at one point to return to England, but he moved to Port Hope, taught school briefly, and then began to study law. After a period in the office of George Strange Boulton*, Draper was called to the bar in 1828. He was also for a time assistant registrar for Durham and Northumberland counties. In 1829 he was given a position in the York office of John Beverley Robinson*, who was soon to be chief justice, before entering into a legal partnership with Solicitor General Christopher Hagerman*. He was also appointed reporter for the Court of King’s Bench and named a bencher of the Law Society of Upper Canada. His reputation as a particularly fluent Tory barrister grew rapidly. He early achieved considerable success in the courtroom, and his eloquence gained him the sobriquet “Sweet William.”

Good fortune, ability, and a pleasing personality thus brought Draper quickly into the society of the group so influential in governing the colony – the “Family Compact.” He was soon acquainted with the most formidable man of them all – John Strachan*, later the first Church of England bishop of Toronto. It was Robinson, however, who actively persuaded Draper to enter politics; this course was directly against the young lawyer’s wishes, but it was no doubt suggested to him as the quickest route to where his ambitions lay: the judiciary.

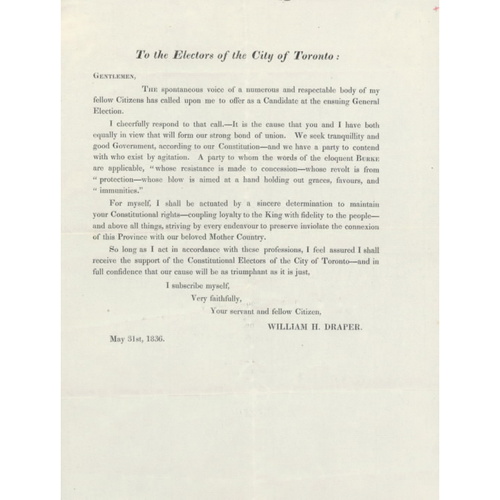

Draper’s political debut was made in the election of 1836 when he handily defeated the Reform candidate in Toronto, James Edward Small*. He took his position among the Tory majority gained in Upper Canada that year through the unprecedented intervention in party politics of the governor, Sir Francis Bond Head. In his first session in the House of Assembly, Draper was active, and his position on such thorny problems as the clergy reserves and the charter of King’s College early indicated a man less intransigent than the majority of his Tory colleagues. In matters pertaining to the Upper Canada Academy (later Victoria College) in Cobourg his favourable report gained him the friendship of Egerton Ryerson* and the Wesleyan Methodists, which was to be one of the constants of his political career. Yet Draper was by no means alienated from his Family Compact friends, and because of their influence with Head his rise was swift. In December 1836 he was made a member of the Executive Council, and, in the following March, solicitor general. Shortly afterwards, Head dispatched him to London to present the governor’s position in the acute financial crisis of 1836–37. This, however, was a painful episode: Draper’s awkward reception by the Colonial Office officials possibly reflected their dislike of Head.

Shortly after Draper’s return, the colony was immersed in the rebellion of 1837. It was to his house, on the night of 4 December, that Head brought his wife and other women and children of the little colonial elite to seek refuge from the expected assault of William Lyon Mackenzie*’s “army.” After the failure of the rebellion Draper organized many of the prosecutions that took place in the next two years when raids by rebels kept the border in constant turmoil. The internal political situation of Upper and Lower Canada was going through an even more basic upheaval with the arrival of Lord Durham [Lambton*] and the British government’s decision to implement that part of his report recommending a union of the two Canadas, the appointment of Charles Poulett Thomson* to make that union a reality, and Lord John Russell’s dispatch of 16 Oct. 1839, which meant in effect that executive councillors could be removed at the will of the governor.

It was during this period of trouble that Draper first began, consciously or not, to tread the pathway towards what was to be the cherished, though unfulfilled, goal of his political career – the formation of a new political party. A conservative party, it would stand ideologically between the old Family Compact Tories, whose system was failing, and the Reformers under Robert Baldwin*, whom Draper believed were endangering the connection with Britain. It was a course that would lead to much vilification. Most of it was undeserved, but Draper soon found himself in an undoubtedly compromising position.

He supported the union of the two Canadas in the Upper Canadian assembly on economic grounds. This action alienated many Tories, but he defended his position by pledging himself to the resolutions introduced by John Solomon Cartwright* in March 1839, which would have heavily weighted the union against the French Lower Canadians and assured a loyal and probably Tory majority in the assembly. Draper ultimately gave up his adherence to the resolutions in the face of Thomson’s determination to force through the union without any such restrictions. However, the publication soon afterwards of Russell’s dispatch of 16 October led most of Draper’s enemies, Tory and Reformer, to look upon it as an explanation of his conduct in changing his position – he was now simply a placeman of the governor. Draper’s denials were not particularly convincing. Though never politically ambitious, he did hope to preserve his place in the government as a route to the judiciary, and there seems little doubt that he bent his principles under Thomson’s iron pressure.

Yet Draper, who succeeded Hagerman as attorney general for Upper Canada in February 1840, did not gain real credit with the governor for his performance. Once Thomson had pushed through the union of the Canadas by February 1841 (and been created Baron Sydenham), he was determined to act as his own prime minister and to destroy the old political groupings, forming a “moderate” party devoted to himself. In the election held in March and April (in which Draper was returned for Russell) Sydenham was successful. The French Canadians stood out against him, but in Canada West (still popularly called Upper Canada) both the old Tories and Baldwin’s Reformers were reduced to a handful of seats by the Moderates committed to the governor. Draper continued as attorney general for Canada West and, as head of the conservative Moderates, was co-government leader with Samuel Harrison* in the assembly. But Draper had only four or five real followers, and Sydenham privately considered him a “poor creature.” It was in Harrison, provincial secretary and leader of the liberal Moderates, that the governor placed his confidence. Unable to comprehend Sydenham’s curious blend of liberalism and autocracy, Draper felt baffled and isolated; he had just written a letter of resignation in the autumn of 1841 when he was informed of the governor’s death.

The arrival of Sir Charles Bagot* as governor in January 1842 marked a new phase in Draper’s career. The two men found both their political views and their personalities compatible, and Draper rapidly replaced Harrison as the governor’s chief Canadian adviser. Also, Draper’s own political philosophy had clarified, and his appreciation of political realities sharpened.

In September 1841, Baldwin had moved resolutions calling for responsible government. These had been parried by Sydenham when Harrison had moved counter-resolutions, ostensibly promising responsible government, in a much vaguer form. It was the Harrison resolutions that were passed, and Draper had supported them. Though he would not have argued that a governor was ever bound to take the advice of his councillors, he now felt himself committed to the principle that executive councillors must have the confidence of a majority of the assembly. This did not necessarily mean a two-party system in the way that Baldwin foresaw; it could also mean a multi-party or a no-party government, and there is no doubt that Draper favoured the last. Now, however, as he began to realize that party government was inevitable, he hoped for a great, loyal Conservative party embracing both French- and English-speaking Canadians – for by now he believed the French to be naturally conservative. He was becoming more convinced that if government were not to founder completely, the French must be brought quickly into it even if they stood by their alliance with Baldwin and the price was a Reform ministry.

It was Bagot who eventually took responsibility for the generous offer to the French assemblymen that led to the formation, in September 1842, of the first government of Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine*. Acclaim for the governor from the French and Reformers, and disapproval from the British government and the Canadian Tories, resulted. Draper’s role in this upheaval was critical: in July he had begun urging Bagot that La Fontaine’s French bloc must be brought into the ministry if the governor were not to be placed in an untenable position by being unable to maintain a council acceptable to the assembly. Other councillors, such as Harrison and Robert Baldwin Sullivan*, were urging this course, but Draper’s advice was the most persuasive. Draper knew that if the French remained committed to Baldwin, their accession to power would necessitate his own resignation. This he magnanimously offered, and advised as well that other Tory councillors be forced out. When Bagot still wavered, Draper and Harrison led the Executive Council in forcing his hand by threatening a mass resignation on 12 September. The following day, to La Fontaine, Bagot made his ultimate offer, to place four French Canadians and Baldwin on the council and to retire councillors in whom they did not have confidence. When Baldwin caused further difficulties, Bagot empowered Draper to read out in the assembly the extent of this offer. Most of the French members had not previously known of the magnitude of the concessions, and La Fontaine’s hold on his party was briefly shaken. A compromise was worked out and the new Baldwin–La Fontaine ministry formed in a way least damaging to the governor’s prestige. Draper resigned from the Executive Council (on 15 September) and from the assembly, and was promised a seat on the judiciary by Bagot.

Draper retired from active politics altogether, taking no great interest in the Legislative Council, to which Bagot appointed him shortly before the governor’s death in 1843. Late the same year, however, a crisis erupted under Bagot’s successor, Charles Metcalfe*, and, led by Baldwin and La Fontaine, the whole of the Executive Council, except Dominick Daly*, resigned. When Metcalfe could not form an administration that had a majority in the assembly, he summoned Draper and gave him a seat in the Executive Council. With only Daly and Denis-Benjamin Viger*, he carried on the administration for nearly a year though he did not hold any portfolio. The non-responsible government of this “triumvirate” was loudly condemned as autocratic, yet Draper was working towards a broadly based “Ministry of Moderates,” like the one that had worked under Sydenham. He failed. In Lower Canada, Viger brought over a few individuals, including Denis-Benjamin Papineau*, to his cause, but no mass support. In Upper Canada, Draper’s appeals to such prominent moderates as Harrison, William Hamilton Merritt*, and Ryerson all foundered, and William Morris*, who wielded great influence with the Presbyterians, was the only notable accession to the Executive Council (as receiver general) that Draper was able to secure.

Yet a government was somehow patched together in time for the general election in the autumn of 1844. A number of factors – the removal of the seat of government from Kingston to Montreal, the secret societies bill, which had outraged the Orangemen under Ogle Robert Gowan, and a general feeling that the French Canadians were being pandered to – had turned much public opinion in Upper Canada against the Reformers before their resignation, and Metcalfe was able to capitalize on this discontent when he entered the campaign and denounced the Reformers as traitors. The result was that, though defeated in the lower half of the province, the government triumphed in Upper Canada and Draper’s ministry had a small majority of four or five.

Draper was now in a curious position for one who had resisted so long the doctrines of Baldwin. From late 1844 until his resignation in May 1847 he was virtually prime minister of Canada, and as he had a majority in the assembly, the Reformers could no longer term his administration irresponsible. At the same time, Metcalfe’s rapidly failing health and the lack of interest in domestic politics shown by his successor Lord Cathcart [Charles Murray Cathcart*] meant that Draper saw hardly any interference from above. Yet this was not the greatest anomaly in his situation. He was also a party leader without a party, a prime minister without a following. His majority in the assembly was made up mainly of Tories who had little love for Draper but had been elected to support the governor, and who were largely excluded from the Executive Council. They endured the attorney general as leader because there was no one else to take his place – he had the support of the governors, and the Tories themselves were split into factions led by Henry Sherwood* and Sir Allan MacNab*.

Under the circumstances, Draper envisaged a period of retrenchment with few controversial issues. In fact, despite the weakness of his position, the last two sessions of the assembly he faced as attorney general saw several important measures. A schools act for Lower Canada drafted by Augustin-Norbert Morin* was passed in 1845. The Upper Canada common school act of 1846, drawn up by Ryerson at Draper’s behest, has been termed the first really workable settlement of that troublesome problem. The voting of a permanent civil list firmly established the principle that it was only the Canadian legislature that had the right to tax Canadians. Perhaps more significant were Draper’s efforts to lay the spectre of the rebellion of 1837. On 17 Dec. 1844 the house addressed the queen, unanimously asking her to pardon all former rebels; two months later, an amnesty was granted. Early in 1845 D.-B. Papineau moved a successful rebellion losses bill for Upper Canada, although the more controversial subject of indemnifying Lower Canadians was not solved until later. Nevertheless, the French Canadians welcomed the repeal of restrictions on the French language, which had been moved by Papineau on behalf of the government, in February 1845. It proved a coup for Draper, who had persuaded Metcalfe to disobey his instructions on the subject in order to forestall an address the Reformers were planning to make on the subject of the French language.

Despite such successes, Draper’s government gave an appearance of chronic weakness. It was defeated frequently on minor issues and retreated ignominiously over the university bill. This measure, which Draper considered important enough to warrant his leaving the Legislative Council and seeking a seat in the assembly (for London), was introduced by him on 4 March 1845. It called for a University of Upper Canada to which Queen’s College at Kingston and Victoria College would be affiliated, as well as the Church of England King’s College (which later became the University of Toronto). Acceptable to the Methodists and the Church of Scotland, the bill aroused the ire of the Church of England, and Strachan managed to rally many of the Tory assembly members against it. Draper persisted, saying he would stand or fall by the measure, and he forced the resignation of his own recently named inspector general, William Benjamin Robinson, on the floor of the house when the latter supported Strachan. Perhaps Draper was hoping for aid from Baldwin’s Reformers, who had previously framed a similar bill. It was not forthcoming. In the end, a group of Tories, led by Sherwood, threatened to bring down the government if the bill had a third reading. This was too much for the ailing Metcalfe who felt that he would not be able to form a new ministry. Following a plea from the governor, Draper’s measure was withdrawn.

From an administrative or legislative point of view, Draper’s ministry could hardly be termed more than a limited success. Politically, it seemed to be a complete failure. Yet the attorney general was working towards something important which would bear fruit after his own political retirement: a modern Victorian conservative party. His plan was twofold – to placate the leading English-speaking Tories while he replaced them with Moderates, and to win the French bloc, or a substantial part of it, away from its alliance with the Reformers.

In this last task Draper came remarkably near to success. There was no longer any hope that Viger or D.-B. Papineau would bring in any mass support, so Draper struck shrewdly at the weakest link of La Fontaine’s supporters, the Quebec City wing, which felt neglected by their Montreal leaders. Negotiations with René Caron, the mayor of Quebec and speaker in the Legislative Council, broke down when Metcalfe refused to eject Daly from the Executive Council and when the correspondence fell into the hands of La Fontaine, who read it in the assembly in April 1846. Further negotiations conducted in the autumn of 1846 came to nothing, but on this occasion Draper managed to drive a wedge between La Fontaine and his chief lieutenant, Morin. In the spring of 1847 approaches were again made to Caron and the Quebec wing of the party, which in turn applied pressure on Morin; in his last approach Draper came closest to success. A large number in the French bloc bypassed La Fontaine and empowered Caron to enter the administration if the “double majority” principle was offered. Acceptance, however, would have given four out of the seven seats on the council to the French members, and it seemed a prohibitive demand. Draper was well content to wait.

The negotiations were never again to be taken up. Draper’s failure to break the French bloc was matched by a more disastrous failure to contain rising Tory opposition to himself. The departure in 1845 of Metcalfe, whom the Tories had pledged to support and who had himself fully supported Draper, was a serious blow. Nevertheless, factions led by Sherwood and MacNab kept the Tories disunited and provided Draper with the opportunity to pursue his hope of filling the Upper Canadian section of his Executive Council with moderate Conservatives. William Morris, John Hillyard Cameron, John A. Macdonald* – these were the type of men Draper wanted and ultimately brought into his ministry. William Badgley* became attorney general east. But they were too few. Attempts to placate the Tories with positions failed. Sherwood and W. B. Robinson had been brought into office but both had to be ejected, and dealings with MacNab proved disastrous. Only a few men such as William Cayley* were acceptable to both right and left wings of the party. The Tory members of the assembly increasingly chafed under the leadership of men whom many of them despised.

That Draper, who had always disliked politics, should begin to look towards retirement under such discouraging conditions was natural. A further inducement came with the appointment of Lord Elgin [Bruce*] as governor in 1847. Since Draper had answered Metcalfe’s desperate summons to office in 1843, he had assumed that British governors would be interested, above all, in avoiding a Baldwin administration. But Elgin and Lord Grey in the Colonial Office were quite willing to accept both responsible government and Baldwin. It was becoming apparent to Draper that he was in the way of everyone – governor, Tory, and Reformer. On 28 May, following the death of Christopher Hagerman, Draper resigned as attorney general and became puisne judge of the Court of Queen’s Bench of Upper Canada. His ministry fell into the hands of Sherwood until the subsequent election returned Baldwin and La Fontaine.

Draper’s legislative accomplishments were real but modest, his efforts to form a moderate Conservative party in alliance with French Canadians failed, and he swam clearly, if obliquely, against the historical tide of responsible government and reformism. Yet it was he, along with Baldwin and La Fontaine, who really dominated the 1840s. Moreover, the formation of a Conservative party linked to French Canadians was to become a reality in 1854. It was the creation of Draper’s ablest follower, Macdonald, who clearly had the political gift in which Draper was most lacking – the ability to organize a national party with wide popular support.

There are other important aspects to Draper’s political career that have rarely been appreciated. Following the conflicts of the 1830s, the 1840s were comparatively quiet, owing partly to a reaction against the rebellion, partly to the Baldwin–La Fontaine alliance. Giving the French Canadians their fair share of political power was a factor and Draper’s critical part in that episode is clear. Similarly his efforts to form a coalition with the French Canadians between 1844 and 1847 undoubtedly helped to convince them that their claims for office would eventually be met.

Draper’s role in the evolution of responsible government was an unwitting one, but perhaps his most important. After the rebellions and the era of Durham and Sydenham, the tide was moving towards acceptance of responsible government. But between 1841 and 1846, when Sir Robert Peel’s Conservative ministry was in power in England, particularly when Stanley held sway in the Colonial Office, a different view prevailed there. An unremitting clash between a Canadian legislature championing responsible government and a British Colonial Office and governor could have had serious consequences in this period, and such a clash appeared about to develop in December 1843 with the resignation of Baldwin and La Fontaine. Draper stepped into the breach, first by supporting Metcalfe with his temporary government, and then from 1844 to 1847 by carrying on a full administration that stood on a majority in the assembly after the election of 1844. Thus he neatly bridged the transition between the era of Metcalfe and Stanley and that of Elgin and Grey. In doing so, he helped allow responsible government to evolve peacefully, and was thus one of the many architects in the development of commonwealth from empire.

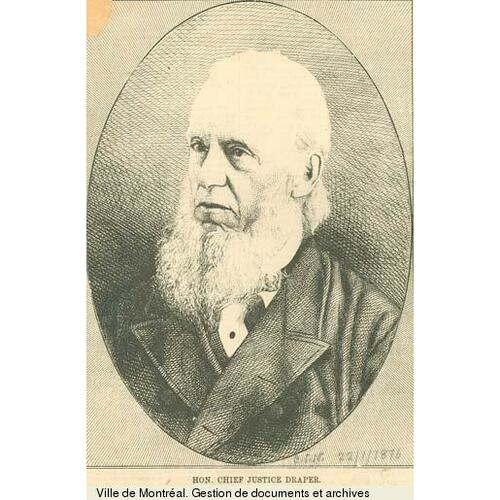

Following his retirement from politics, Draper was at last given the opportunity to advance in what had always been his chosen field of endeavour – the judiciary. After sitting on the Court of Queen’s Bench for nine years, he was created chief justice of the Court of Common Pleas of Upper Canada in 1856, succeeding James Macaulay*. In 1863 he was named chief justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench for Upper Canada; in 1868 he was appointed presiding judge of the Court of Error and Appeal in Ontario, succeeding Archibald McLean*, and the next year became its chief justice.

Though eminently distinguished, Draper’s later career saw none of the turbulence, nor indeed of the constructive innovations that had marked his political life. To Draper himself it was the consummation of a personal preference for a tranquil and ordered existence. He did, however, make two brief reappearances in the public eye in the 1850s – in the question of transferring the Hudson’s Bay Company territories, and as presiding judge over the “double shuffle” trials.

The HBC question arose when problems concerning the colony of Vancouver Island prompted Henry Labouchere, colonial secretary in Lord Palmerston’s administration, to undertake an investigation in 1857 of the company’s charter by a select committee of the British House of Commons [see John Palliser*]. In the Canadas, the Macdonald–George-Étienne Cartier government was weak, and the Clear Grit opposition, led by George Brown, had just hammered “western expansion” into its platform. Though Macdonald was happy to preempt an attractive Grit policy, he knew the difficulties of occupying and defending the lands, and therefore had to pursue a policy combining aggressive expansionism with prudent realism. He chose Draper to represent Canada before the select committee, with no powers to commit the province but with wide latitude of argument. It was a task suited to Draper’s broad legal knowledge and persuasive powers of argument. Labouchere claimed that Draper, who favourably impressed the committee, was one of the ablest men he had ever met. Concentrating on the necessity of preserving the west from American encroachments, Draper argued that only settlement could achieve this but that the company’s interests were inimical to settlement. He suggested that an appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council might be the best way to test the company’s chartered territorial rights.

The work of the select committee bore no immediate fruit, but Draper’s arguments had made their mark, and the principle that Canada would likely be the ultimate legatee of the HBC’s territorial rights became more and more taken for granted.

Draper’s next appearance on the political scene in 1858 was a good deal more controversial. In August the Cartier–Macdonald ministry came back into power after a defeat which had resulted in the famous two-day Brown–Antoine-Aimé Dorion* administration. The new ministers did not resign their seats and face by-elections as was normal procedure. Instead they swore the oaths for one office, resigned, and swore again for another office. The manœuvre was soon dubbed the “double shuffle,” and Brown bitterly attacked both the governor, Sir Edmund Head*, who had accepted it, and the government. Another Reformer, Adam Wilson*, tested the legality of the issue by starting proceedings against Macdonald and two of his colleagues, and the case was heard before Draper and William Buell Richards*. Despite the fact that the judges involved in the hearings were Conservatives, the Grits appear to have hoped for victory. However, it was on the letter of the law that Draper stood in giving judgement for the defendants on 18 Dec. 1858. Yet, though disclaiming any right of the judiciary to guess what the legislators intended in framing the original act [see Harrison], Draper did interpret what they had “meant” in dealing with another, more minor point in the issue. This lent some credence to the charges Brown and his allies soon made that both the governor and the judiciary were in an unholy alliance to subvert the constitution at the behest of the corrupt Macdonald. Draper was singled out for particular contempt, and the Globe expounded: “Mr. Draper has mistaken his place and age. He would have made a very fair Jeffreys and might have served for the Bloody Assize.” The charges by the Grits of a conscious conspiracy were unfounded and unfair, but the whole episode of the “double shuffle” was hardly edifying. The bias in Macdonald’s favour and against Brown must, unconsciously at least, have influenced Head and Draper in making their otherwise unexceptionable decisions.

If the remainder of his years on the bench were quiet, Draper was active in many civic and religious organizations, being at one time president of the St George’s Society in Toronto, of the Canadian Institute (from 1856 to 1858), of the Toronto Cricket Club, and of the Philharmonic Society. He was president of the Church Association of the Diocese of Toronto, formed in 1873 and including as members William Hume Blake*, Casimir Stanislaus Gzowski*, and Daniel Wilson*, which led to the founding of Wycliffe College in Toronto. In 1854, he was made a cb. He maintained a lifelong passion for exercise but became increasingly infirm in the last decade of his life, and he died on 3 Nov. 1877.

Draper had received a licence to marry Augusta White on 10 Jan. 1826, and they wed later that year. She was a lively, enterprising woman who volunteered in the city’s hospitals and cholera sheds during the outbreaks between 1849 and 1854. She maintained a correspondence during her “60 years of uninterrupted friendship” with Edward John Trelawny, the English adventurer, writer, and companion of Percy Shelley and Lord Byron. While in England in November 1876, the Drapers visited Trelawny at his cottage in Sompting, Sussex. Augusta was 90 years old when she died on 25 Sept. 1887.

The Drapers had several children, one of whom, Francis Collier Draper*, became well known as Toronto’s police chief.

MTCL, Baldwin papers. PAC, MG 24, A13 (Bagot papers); E1 (Merritt papers); MG 26, A (Macdonald papers). PAO, John George Hodgins collection; John Strachan letter books; John Strachan papers. PRO, CO 42/437–42/550; CO 537/140–537/143.

Arthur papers (Sanderson). [Bruce and Grey], Elgin-Grey papers (Doughty). Canada, Province of, Legislative Assembly, Journals, 1841–47. Correspondence between the Hon. W. H. Draper & the Hon. R. E. Caron; and between the Hon. R. E. Caron, and the Honbles. L. H. Lafontaine & A. N. Morin (Montreal, 1846). [C. T. Metcalfe], The life and correspondence of Charles, Lord Metcalfe, late governor-general of India, governor of Jamaica, and governor-general of Canada . . . , ed. J. W. Kaye (2v., London, 1854). [Ryerson], Story of my life (Hodgins). [C. E. P. Thomson], Letters from Lord Sydenham, governor general of Canada, 1839–1841, to Lord John Russell, ed. Paul Knaplund (London, 1931). Upper Canada, House of Assembly, Journals, 1836–40. British Colonist (Toronto), 1838–47. Christian Guardian (Toronto), 1836–47. Examiner (Toronto), 1838–47. Globe (Toronto), 1844–47.

Cyclopædia of Can. biog. (Rose, 1886). Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, II. Careless, Union of the Canadas. Creighton, Macdonald, young politician. G. P. de T. Glazebrook, Sir Charles Bagot in Canada; a study in British colonial government ([London], 1929). George Metcalf, “The political career of William Henry Draper,” unpublished ma thesis, University of Toronto, 1959. Moir, Church and state in Canada West. Monet, Last cannon shot. Ormsby, Emergence of the federal concept. D. B. Read, The lives of the judges of Upper Canada and Ontario, from 1791 to the present time (Toronto, 1888). Sissons, Ryerson. George Metcalf, “Draper Conservatism and responsible government in the Canadas, 1836–1847,” CHR, XLII (1961), 300–24.

Bibliography for the revised version:

Ancestry.com, “London, England, Church of England baptisms, marriages, and burials, 1538–1812,” William Henry Draper, 10 Apr. 1801; “London, England, Church of England marriages and banns, 1754–1938,” Henry Draper and Mary Louisa Oliver, 19 June 1798; “Ontario, Canada, marriages, 1826–1937,” Francis Collier Draper and Ellen Teresa Routh, 28 Dec. 1881: www.ancestry.ca (consulted 23 Aug. 2022). Library and Arch. Can. (Ottawa), R233-34-0, Ont., dist. East York (45), subdist. Yorkville (B): 33. Museums of Mississauga, Ont., 2004-2-277 (certificate of baptism, Augusta White, 22 Jan. 1795); 2005-1-87-2 (marriage license, William Henry Draper and Augusta White, 10 Jan. 1826). Globe, 26 Sept. 1887. Shelley and his circle, 1773–1882, ed. K. N. Cameron et al. (10v., Cambridge, Mass., 1961–2002), v.5 (1973).

Cite This Article

George Metcalf, “DRAPER, WILLIAM HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 27, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/draper_william_henry_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/draper_william_henry_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | George Metcalf |

| Title of Article: | DRAPER, WILLIAM HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | April 27, 2025 |