Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

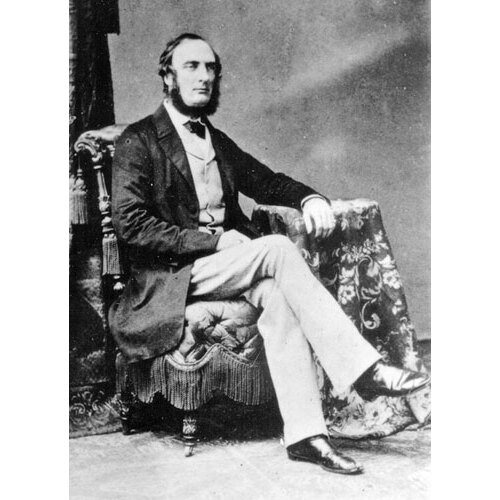

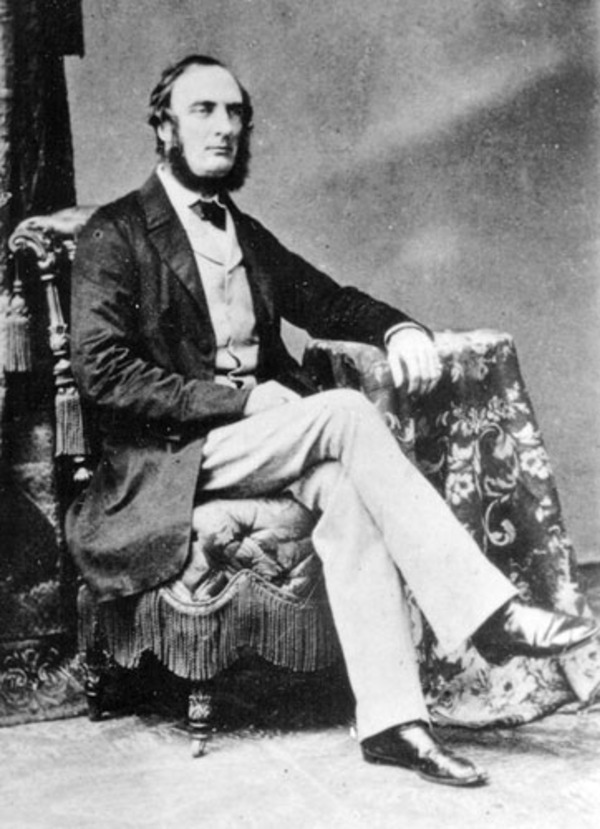

PALLISER, JOHN, landed gentleman, big game hunter, and explorer; b. 29 Jan. 1817 in Dublin (Republic of Ireland), eldest son of Colonel Wray Palliser and Anne Gledstanes; d. 18 Aug. 1887 at Com[e]ragh House, Kilmacthomas, County Waterford (Republic of Ireland).

John Palliser belonged to a distinguished Irish family founded by William Palliser, archbishop of Cashel, who had come to Ireland from Yorkshire, England, to enter Trinity College, Dublin, in 1660. The devoutly Protestant Pallisers combined social eminence and a lively social, artistic, and intellectual life with a tradition of public service and conservative politics. They travelled extensively, living not only in Ireland at Derryluskan House, County Tipperary, at Comragh House, and in Dublin, but also in London, Rome, Florence, Paris, and Heidelberg.

Palliser was largely educated abroad and spoke French, German, and Italian, though in English his spelling was erratic. He entered Trinity College, Dublin, in 1834, attended intermittently, and abandoned his studies in 1838 without taking a degree. Other interests and activities claimed him. His family’s social position carried obligations and he served as high sheriff in 1844, and later as deputy lieutenant and justice of the peace. On 20 Sept. 1839 he had received an appointment as captain in his father’s regiment, the Waterford Artillery Militia, but no record has been found of any active service until the regiment was embodied on 14 Jan. 1855. He was on duty most of that year, attending artillery drill at Woolwich (now part of London), England, from 6 February to 6 May and afterwards commanding a detachment at Duncannon Barracks in County Wexford. When the regiment was mustered in 1857 Palliser was in North America. He saw service again briefly in 1862, but was once more abroad when the regiment was mustered in 1863, and resigned his commission to take effect on 14 July 1864. Though he is usually referred to as Captain Palliser, he does not appear to have had any other military experience.

The ruling preoccupation of Palliser, and most of his brothers and friends, seems to have been travel “in search of adventure and heavy game.” One of these friends, William Fairholme, who was to become his brother-in-law in 1853, went buffalo hunting in 1840 on the “Grand Prairies of the Missouri.” In eager emulation, Palliser set off in early 1847 on a visit to the New World which was to include “the regions still inhabited by America’s aboriginal people . . . that ocean of prairies extending to the foot of the great Rocky Mountains.” He spent 11 months on the prairies hunting buffalo (“a noble sport”), elk, antelope, and grizzly bear, and observing the life of the Indians and fur-traders. He left the west in 1848 and visited New Orleans and Panama before returning home in 1849. Back in London, where he lived with his great friend William Sandys Wright Vaux of the British Museum, Palliser wrote a lively book about his North American adventures, Solitary rambles and adventures of a hunter in the prairies, published in London in 1853, and it went through a number of editions.

Anxious to return to the western plains, Palliser, elected a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society on 24 Nov. 1856, submitted to the society a plan for the exploration of the southern prairies of British North America and the adjacent passes through the Rocky Mountains. His proposal was for a personal journey, with local voyageurs and hunters, across the little known plains and mountains immediately north of the 49th parallel. Keenly aware of official American explorations underway since 1853 to discover railway routes to the Pacific, the society took immediate action. It decided to recommend a more ambitious enterprise which would include scientific assistants, and asked the Colonial Office for a grant of £5,000 to finance the project.

John Ball, under-secretary of state for the colonies and an old friend of Palliser’s, strongly supported the project, but added a third facet to it by insisting that the old North West Company canoe route be examined to help the Colonial Office judge whether or not the western plains were accessible from Canada by a route entirely within British territory. Little dependable information was available about the geographic features of the plains, their geology, climate, flora, fauna, and resources. Moreover, their “capability for agriculture” and settlement was a matter of dispute between the Hudson’s Bay Company and its critics. Palliser was one of the few men with experience of travel on the prairies who was detached from the growing controversy about the future of western British North America. Ball and the colonial secretary, Henry Labouchere, thought that he would be an impartial observer and provide the knowledge for which they had such an urgent need – a need emphasized by the contradictory testimony heard by the select committee of the House of Commons on the HBC which began its hearings on 18 Feb. 1857 and reported late in the summer. The government of Canada was equally concerned about the future of the west and in the same year organized its own exploring expedition, led by George Gladman* in 1857, and by Henry Youle Hind* and Simon James Dawson* in 1858.

Ball worked closely with Palliser on detailed plans, and they consulted the Royal Society and such eminent scientists as Major-General Edward Sabine, Sir William Jackson Hooker, Sir John Richardson*, and Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, president of the Royal Geographical Society. They also consulted the few travellers who had experience west of the Great Lakes, and, most important of all, Sir George Simpson*, governor of the HBC territories in America. The HBC still provided the only means of communication with, and sources of supplies in, Rupert’s Land and the Indian territories beyond; Simpson’s assistance would be vital to the success of the expedition.

The Treasury was at last induced, largely through Ball’s efforts, to make the appropriation of £5,000, which had later to be increased, as the cost of the expedition in the end came to a total of some £13,000. A technical team was recruited consisting of Dr James Hector, geologist, naturalist, and physician, Eugène Bourgeau*, botanical collector, Lieutenant Thomas Wright Blakiston, ra, magnetical observer, who also made ornithological observations as a matter of personal interest, and John William Sullivan, secretary and astronomer. Scientific instructions were formulated individually by the learned authorities concerned, but Palliser, under instructions from the secretary of state for the colonies, was accepted as leader of the expedition – a formidable assignment for a country gentleman without business experience or professional training, though he alone of the party had had any experience in the west.

Palliser sailed for New York on 16 May 1857 with Hector, Bourgeau, and Sullivan. At Sault Ste Marie they picked up two waiting canoes with their voyageur crews and proceeded by steamship across the ice-covered Lake Superior to Isle Royale, Mich. There, on 12 June, they embarked in the canoes and after a month’s arduous paddling and portaging reached Lower Fort Garry (Man.) on the Red River. While organizing men, horses, carts, provisions, Indian presents, ammunition, and other supplies, for which Simpson and the HBC had made preparation, the explorers consulted knowledgeable local people and studied the Red River Settlement.

On 21 July the expedition started on its journey across the plains, heading south up Red River to the American boundary, where they made careful observations in conjunction with a chance-met American land surveyor, Charles W. Iddings. From Pembina (N. Dak.) the party travelled west via St Joseph’s (Walhalla) and Turtle Mountain (Man.) to Fort Ellice where they were joined by James McKay*, a noted mixed-blood guide. They made a quick trip to the boundary at Roche Percée (Sask.) before setting off for the South Saskatchewan River. Near the Elbow they turned northeast to Carlton House (Sask.) on the North Saskatchewan River, which was to be their base for the winter. Palliser went off via St Paul (Minn.) to New York to make application to the Colonial Office for more time and more money. While waiting for a reply he revisited New Orleans, returning to Carlton House for an early start in the spring of 1858. Meanwhile, Blakiston had joined the party at Carlton House, having brought the delicate instruments needed for magnetical observations by way of Hudson Bay, and he carried on hourly observations. Hector had journeyed to Fort Edmonton to recruit men for the next season’s work.

On Palliser’s arrival, the explorers headed west between the two branches of the Saskatchewan River. Near modern Irricana (Alta) the party separated to probe into the mountains for feasible passes. Palliser and Sullivan made a dash to the American boundary before crossing the mountains by the North Kananaskis Pass. Returning by the North Kootenay Pass, they rejoined the rest of the party to winter at Edmonton.

Blakiston, who had traversed both Kootenay passes, now left the expedition because of a quarrel with Sullivan which had widened to include Palliser. Hector had crossed the mountains through Vermilion Pass and returned by the Kicking Horse Pass; he devoted the winter to further exploration. Palliser hunted and examined the country south and east of the fort and then, with two newly arrived friends, Captain Arthur Brisco and William Roland Mitchell, travelled to Rocky Mountain House (Alta) to get to know the Blackfoot and Piegan Indians who frequented it, as he planned to travel through their country the next season. At Fort Edmonton the whole party enjoyed the hospitality of Chief Factor William Joseph Christie* and the highly sociable Palliser, with the aid of Mrs Christie, gave a tremendous ball.

In its final season, 1859, the expedition travelled southeast to the forks of the Red Deer and South Saskatchewan rivers in an attempt to connect with their westernmost point in 1857, and then south to the Cypress Hills, where the party broke up. Brisco and Mitchell went to Fort Benton (Mont.) and down the Missouri. Hector travelled northwest to cross the Rockies by Howse Pass in a final but unsuccessful attempt to discover a way through to the Pacific coast. Palliser and Sullivan journeyed directly west, then north, to cross the mountains by the North Kootenay Pass and follow the Kootenay River down to the Paddler’s Lakes (Bonners Ferry, Idaho). Sullivan took the horses overland to Fort Colvile (Colville, Wash.), while Palliser voyaged down the Kootenay River and Lake in an Indian canoe.

At Fort Colvile Palliser and Sullivan re-equipped themselves to cross the border again for a final attempt to complete exploration of a route through British territory. Palliser sent Sullivan eastward from Fort Shepherd (B.C.) on the Columbia River while he himself forced a way west through difficult country until, near modern Midway (B.C.), he fell in with an American party engaged on the Boundary Survey of 1857–62. He had already encountered Lieutenant Henry Spencer Palmer*, re, who had studied the HBC trail from Fort Langley on the lower Fraser to Lake Osoyoos and assured Palliser that it lay north of 49º. Palliser was thus satisfied that a route through British territory had been established. Back at Fort Colvile, Palliser and Sullivan were rejoined by Hector before beginning the difficult trip down the Columbia and on to Victoria, then home via San Francisco and Panama. Palliser detoured to Montreal to visit Simpson, and reached Liverpool on 16 June 1860.

Before the work of the expedition was finished a final report had to be written and its bills, which greatly exceeded the Treasury appropriations, verified and settled. Members of the party spoke at meetings of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the Royal Geographical Society, the Geological Society of London, the Ethnological Society of London, and the Botanical Society of Edinburgh. The reports, which appeared in 1859, 1860, and 1863, and the great map (1865) provided the first comprehensive, careful, and impartial observations to be published about the southern prairies and Rocky Mountains in what is now Canada. An essential source of information for the precursors of settlement, such as the North-West Mounted Police, the boundary surveyors, railway planners (notably Sir Sandford Fleming*), and other travellers, they are still useful. They added considerably to geographical knowledge of the region, and established that an extensive “fertile belt,” well suited for stock-raising and cultivation, bordered the semi-arid prairie land of the south which is today known as “Palliser’s Triangle.” They emphasized the difficulty and expense of any possible route from Fort William (Thunder Bay, Ont.) to Red River, the old NWC canoe route. Settlers with cattle would prefer the much easier route through the United States; only mineral discoveries would provide economic justification for a route north of the border. They concluded that, though a railway might be built through the Rockies by one or other of the passes examined by the expedition, the cost of pushing road or rail through to the Pacific by any route entirely within British territory would be prohibitive. They urged the importance of providing for the future of the Indian inhabitants of the west before the buffalo disappeared and settlers began to flood into the country. The expedition had itself managed to avoid any serious clash with the plains Indians, but foresaw danger when settlement began.

The detailed records and observations of the expedition are largely attributable to Palliser’s colleagues, but the fact that there was an expedition at all – an expedition which demonstrated to American expansionists the interest of the imperial government in the west – was a result of his initiative, while the extraordinary extent of country covered in three seasons owes much to his skill and zest as a traveller. The expedition earned Palliser the gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society in 1859, and, in 1877, a cmg.

Palliser succeeded to the family estates on his father’s death in November 1862. That same year he went off to the West Indies on a semi-official mission, the nature of which remains a mystery. However, it is known that from Nassau he ran the “Yankee” blockade to visit the Confederate states. In 1869 he undertook yet another notable voyage, this time with his brother Frederick Hugh, in his own specially reinforced craft, to Novaya Zemlya (U.S.S.R.) and the Kara Sea. Again, big game and exploration were twin objectives.

Such ventures were costly. Born to wealth, neither Palliser nor his brothers seem to have been able to adapt themselves to a serious decline in the family fortune. Frequent travel meant that Palliser was not often at home to look after the family estates. These estates were heavily mortgaged, and had to be rescued by Fairholme money. When Palliser died they passed to his eldest niece, Caroline Fairholme. She, with her mother and her sisters, as well as with Frederick’s family, had found a home with her unmarried, dearly loved uncle at Comragh House. There John Palliser died. He lies in a grave in little Kilrossanty churchyard.

[This biography is based essentially on the same scattered and fragmentary sources as were used and recorded in my editorial work on the Champlain Society’s volume, The papers of the Palliser expedition, 1857–1860 (Toronto, 1968). A few new fragments of information have come to light since that work was done, in private, personal papers in Denmark and Ireland. These are of marginal interest in relation to Palliser’s career and do not alter the basic ideas and interpretations recorded and discussed in the introduction, notes on sources, and footnotes of The Palliser papers. They have, however, strengthened my impression of the importance of family ties and responsibilities in the explorer’s life, as well as of the influence of a closely knit group of friends. See also my article, “The Pallisers’ voyage to the Kara Sea, 1869,” Musk-Ox (Saskatoon, Sask.), 26 (1980): 13–20. i.m.s.]

Cite This Article

Irene M. Spry, “PALLISER, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 6, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/palliser_john_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/palliser_john_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Irene M. Spry |

| Title of Article: | PALLISER, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | March 6, 2026 |