Source: Link

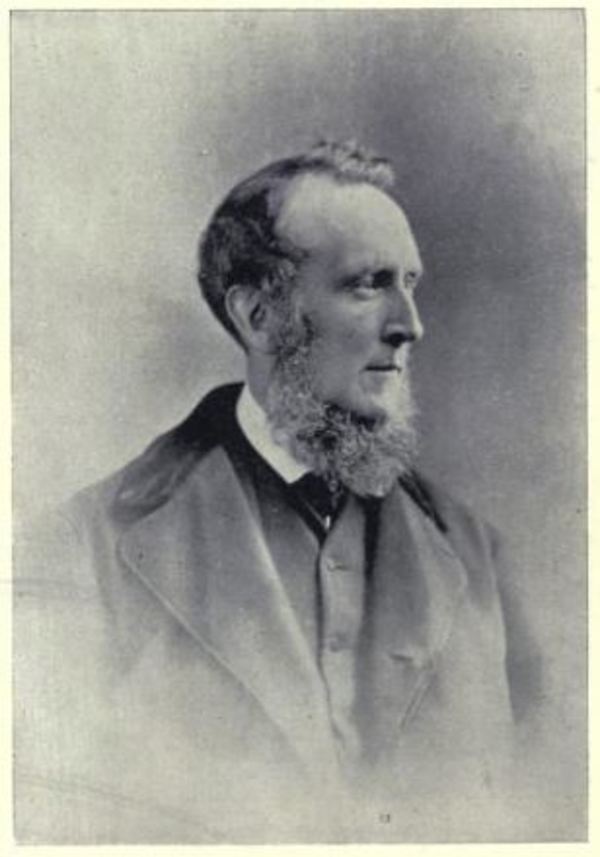

HAGARTY, Sir JOHN HAWKINS, lawyer, teacher, politician, author, and judge; b. 17 Sept. 1816 in Dublin, son of Matthew Hagarty; m. 9 Sept. 1843 Anne Elizabeth Grasett (d. 1888), sister of the Reverend Henry James Grasett*, in Toronto, and they had three sons; d. there 27 April 1900.

The son of an examiner for the Court of Prerogative for Ireland, John Hawkins Hagarty was educated privately and at Trinity College in Dublin, where he stayed for a year (1832–33). He immigrated to Upper Canada in 1834, spending his first year on a farm near Bowmanville. Then, for five years, he was a student-at-law in the office of George Duggan* in Toronto. He was called to the bar in 1840, and from 1846 his law partner was John Willoughby Crawford*, a future lieutenant governor of Ontario. In addition to his busy career as a barrister (he was appointed qc in 1850), Hagarty served as a professor of law at Trinity College in Toronto from 1852 to 1855, the year in which it awarded him a dcl. He was a member of the college’s council between 1857 and 1869.

Hagarty was active among Irish Canadians and in 1846 he was president of the St Patrick’s Society. In January 1847 he was elected an alderman for St Lawrence Ward, but resigned in May of that year; in 1850 he was elected as a public school trustee for St Patrick’s Ward. Hagarty wrote much poetry, most of it published in the Maple-Leaf, or Canadian Annual; a Literary Souvenir, edited by the Reverend John McCaul*. His best-known piece, which does not rise above the mediocre, is a heroic ode, “The funeral of Napoleon, 15th December 1840,” published in the 1849 volume. His literary interests were also shown by membership in the Canadian Institute [see Sir Daniel Wilson], of which he was president in 1861–62.

Hagarty’s major contribution, however, was the 41 years, more than two-thirds of his legal career, he spent on the bench: puisne judge of the Court of Common Pleas (1856–62), judge of the Court of Queen’s Bench (1862–68), chief justice of Common Pleas (1868–78), chief justice of Queen’s Bench (1878–84), and president of the Court of Appeal and chief justice of Ontario (1884–97). As chief justice he served as administrator of the province for short periods in 1882 and 1892. Following his retirement in April 1897, the Canada Law Journal praised his service on the bench. It found that he had “no ambition to extend the area of ‘judge-made’ law but, on the contrary, [was] sincerely solicitous of administering the law as he found it, without usurping or encroaching on the functions of the legislature.” The writer added that Hagarty’s decisions had been upheld more frequently than those of any other judge. A modern observer of his decisions – most concerning the liability of railway companies, insurance, murder, the status of married women, disputed elections, seduction, and slander – could hardly disagree. Yet the writer of 1897 has neglected some of Hagarty’s most engaging qualities as a judge. He wrote with great clarity and showed a meticulous use of language, particularly statutory language. He gave much more thought to statutory interpretation than did his fellow judges. His judgements have a distinctly reflective quality. He often agonized over decision making and frankly expressed his dilemmas. In one case he confessed that he was “much embarrassed” about the state of the law. He dissented in that case; indeed, Hagarty dissented more often than most judges. On another occasion he described a “great regret at being compelled to mention the very great difficulty, I might say impossibility, which the court feels in trying to deal properly” with the issue before it.

Hagarty was involved in only two decisions that can claim to have legal significance. In Drake v. Wigle (1874) the defendant, a tenant for life, was sued for committing waste on the plaintiff’s reversion by cutting down trees on “wild land” for the sole purpose of bringing it into cultivation. Under English law a life-tenant would certainly have committed waste if he destroyed 100-year-old oak trees. The cutting down of fast-growing coniferous trees in the densely forested Canadian bush was different. Hagarty decided that waste was a “flexible term varying with local and other circumstances” and that the arcane real-estate laws of England were not applicable to Canada.

John Anderson*, a fugitive slave who had found refuge and protectors in Upper Canada, was charged by a magistrate’s court in October 1860 with having killed a white man in Missouri who was trying to prevent his escape. That year the Court of Queen’s Bench found Anderson guilty of murder under Missouri law and liable to extradition under the terms of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty with the United States. The following year, on appeal, the case went before judges William Henry Draper*, William Buell Richards*, and Hagarty in the Court of Common Pleas. They decided in favour of Anderson but did so on narrow legalistic grounds related to the formulation of the 1860 charge. Consciously avoiding the larger issues of policy, the judges did not decide that the Webster-Ashburton Treaty could never be applied to fugitive slaves. Hagarty concluded that Anderson should go free because the documentation was faulty, and he justified this narrow approach by its “overwhelming importance to this prisoner’s life and liberty.” In commenting on the larger issues, he said: “Nothing would be easier than to arrive at a conclusion if I had a right to dispose of this case simply on my own ideas of right and wrong, or on the dignity and privileges of human liberty – if, in short, I could ignore my peremptory obligation to decide according to what I believe the law is, and not as I may think it ought to be.”

In recognition of his legal services Hagarty was knighted on his retirement in 1897. A member of the Church of St George the Martyr (Anglican), he died in 1900 and was buried without public ceremony in St James’ Cemetery in Toronto.

In addition to the poem cited in the biography, Hagarty is the author of St. Lawrence Ward: the favour of your vote and interest is requested for John H. Hagarty as alderman for your ward election, on Tuesday, 12th January, 1847, at nine A.M. ([Toronto?, 1847?]), Thoughts on law reform (Toronto, 1850), A legend of Marathon; by an Ontario judge ([Toronto?, 1888?]), and Poems (s.l., 1902).

Trinity College Library, mss Dept. (Dublin), MUN/V/27/7–8 (term/exam books, 1833). York County Surrogate Court (Toronto), no.13897 (mfm. at AO). Richard Armstrong, “Hon. John Hawkins Hagarty, chief justice of Ontario,” Barrister (Toronto), 1 (1894–95): 252–56. Canada Law Journal (Toronto), new ser., 33 (1897): 337–40. “Sir John Hawkins Hagarty,” Canadian Law Times (Toronto), annual digest, 20 (1900), [1st sect.]: 171–78. Daily Mail and Empire, 28 April 1900. Globe, 28 April 1900. Toronto Daily Star, 28 April 1900. Toronto World, 28 April 1900. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. Dent, Canadian portrait gallery. Trinity College, Calendar (Toronto), 1853–55. G. B. Baker, “Legal education in Upper Canada, 1785–1889: the law society as educator,” Essays in the history of Canadian law, ed. D. H. Flaherty (2v., Toronto, 1981–83), 2: 96. Centennial story: the Board of Education for the city of Toronto, 1850–1950, ed. H. M. Cochrane (Toronto, 1950), 30. Charles Clarke, Sixty years in Upper Canada, with autobiographical recollections (Toronto, 1908), 304, 306. Davin, Irishman in Canada. The Royal Canadian Institute, centennial volume, 1849–1949, ed. W. S. Wallace (Toronto, 1949), 193, 306. “Historical value of legal biography,” Canadian Law Times (Toronto), 29 (1909): 450.

Cite This Article

Graham Parker, “HAGARTY, Sir JOHN HAWKINS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hagarty_john_hawkins_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hagarty_john_hawkins_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Graham Parker |

| Title of Article: | HAGARTY, Sir JOHN HAWKINS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |