Source: Link

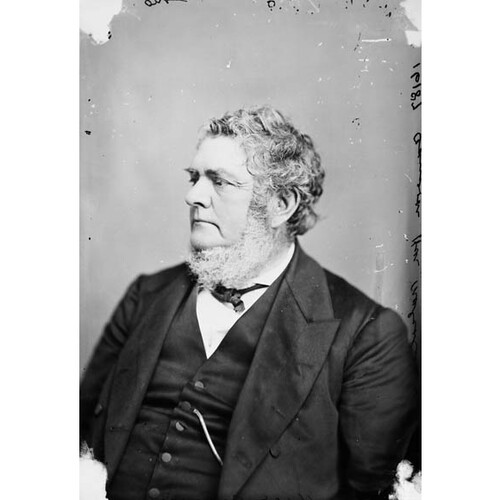

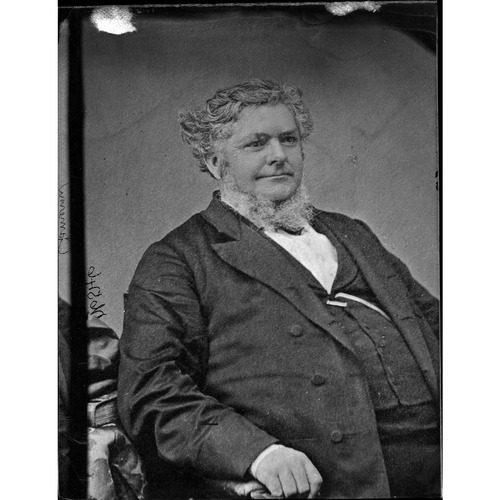

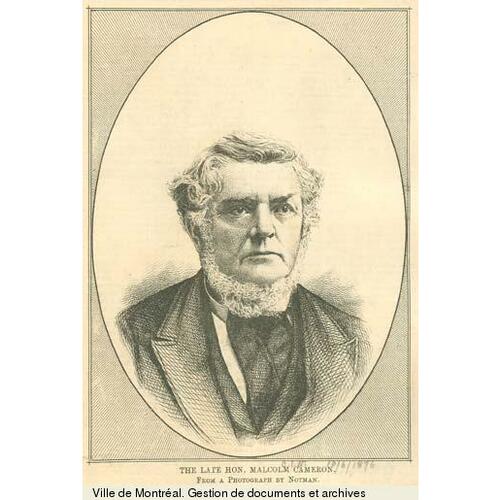

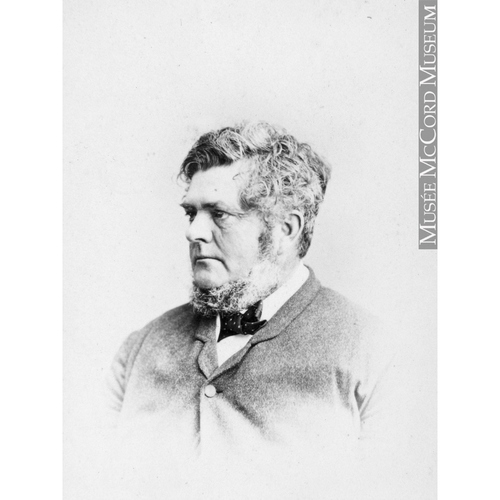

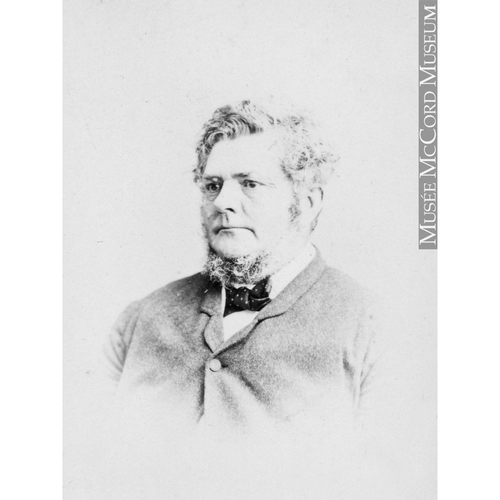

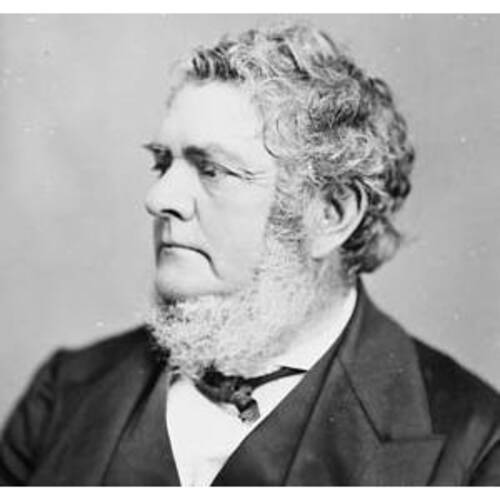

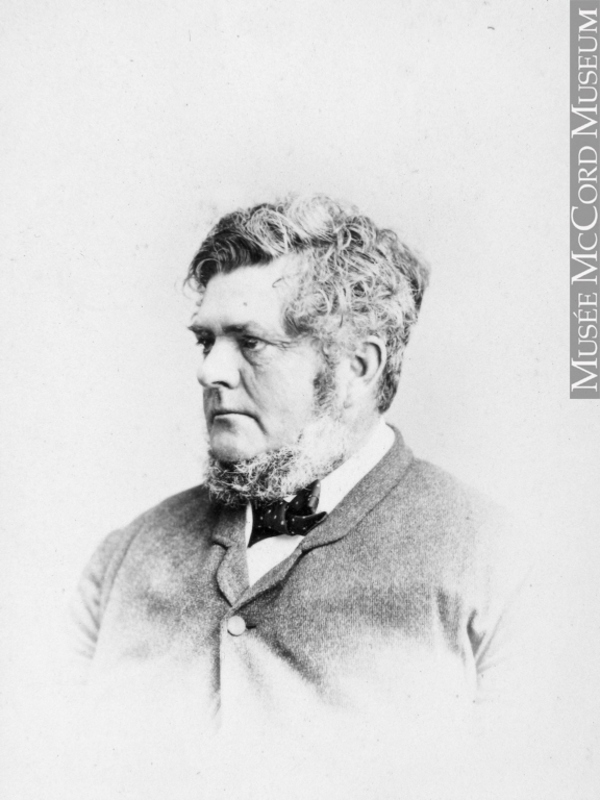

CAMERON, MALCOLM, businessman, politician, and temperance advocate; b. at Trois-Rivières, L.C., 25 April 1808, son of Angus Cameron, a hospital sergeant in a Scottish regiment, and Euphemia McGregor; d. 1 June 1876, at Ottawa, Ont.

Malcolm Cameron, the son of Presbyterian Scots, spent his early years in Lanark County, Upper Canada, where his father settled after the disbanding of his regiment. Angus Cameron established a tavern beside the Mississippi River between Lanark and Perth, and Malcolm, “the barefoot ferry boy,” carried travellers across the river. At 15 he took a position in a store in Laprairie, then worked as a stable boy in Montreal. He returned to Perth where he attended the local school and eventually obtained employment as a clerk in a brewery and distillery.

In 1828 Cameron entered into a short-lived partnership in a general store at Perth with his brother-in-law, Henry Glass. Four years later he, John Porter, and Robert Gemmell set up as general merchants. This business prospered, and while on a purchasing trip to Scotland in April 1833 he married a cousin, Christina McGregor.

Cameron’s business interests expanded in the 1830s. He began dealing in real estate around Perth. In August 1834 he joined with his brother John in establishing the Bathurst Courier; it was to be an independent weekly, the “slave or the tool” of no party, but it was sold one year later because the wealthy and Tory merchants of the area would not advertise in it. Malcolm’s attention had meanwhile moved westward to the St Clair region which had impressed him during a trip in 1833. He established in 1835 a general store at Port Sarnia, which he put under the management of an agent, and purchased 100 acres of what is now downtown Sarnia for £400 from Elijah Harris, deputy of the local Indian agent. The land was divided into lots, some of which he sold in the 1830s and 1840s and at a large auction in April 1857. Conspicuous among those he encouraged to settle were half-pay officers and Scottish weavers who had originally established themselves in Lanark.

Cameron himself moved to Port Sarnia in 1837; on 4 Aug. 1837 the partnership of Porter, Gemmell and Company was dissolved. At Port Sarnia he set up lumber and flour mills and he built ships to transport merchandise along the lakes from Chicago to Quebec City. He also acquired good wooded land in the interior away from Lake St Clair and established a timber business. In 1847 he was a contractor in the building of the Great Western Railway.

Cameron was greatly influenced by Scottish “Radicals” who had settled around Lanark, and in 1836 his interest in politics had led him to run as a moderate Reformer for Lanark. He was elected although he had made no clear statement of his intentions other than to support the connection with Britain and act in the interests of the constituency. He generally sided with Robert Baldwin*, Marshall Spring Bidwell, and other Reformers in opposing Sir Francis Bond Head during the session of 1837. He was in Hamilton when rebellion broke out and he volunteered under Allan MacNab*; 16 days later he resigned when he considered his services no longer necessary. At the end of the 1839 session Cameron exhibited the temper which, along with an unwillingness to commit himself and a tendency to impulsive action, would characterize his later career. On the last night of the session a bill was rushed through to sell the clergy reserves and to place the proceeds in the hands of the imperial government for it to apportion. Judging this action to have been accomplished by force and drunkenness, with “every rule of the House, every pledge of members, every principle of honour in man trampled under foot,” he swore never to enter the house again.

In fact, Cameron did not attend the next session. However he accepted the invitation of a group of friends in Lanark to stand again in the anticipated elections, the first after the union of Upper and Lower Canada (now Canada West and Canada East). He continued his independent stand, making vague promises to support the institutions on which the happiness of the province depended, although he did say he saw in the policies of Lord Sydenham [Thomson*] liberal tendencies he might endorse. He won the seat, and during the session of 1841 supported the administration formed by Sydenham. He had not agreed with Baldwin when the latter resigned, just as the assembly was to convene in 1841, over Sydenham’s refusal to take other Reformers such as Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* into the government. Cameron now consistently voted with the majority against Baldwin, and was placed on a committee to prepare and report on a draft speech in answer to the speech from the throne. It was later said that in 1841 Cameron was offered but refused the post of inspector-general; no proof of this offer seems to exist and observers such as Francis Hincks* questioned the truth of the story. By 1842, however, Cameron returned to his support of Baldwin, and in that year was appointed inspector of revenue under the Baldwin–La Fontaine ministry. He resigned in September 1843 when he could not approve the government bill to move the capital to Montreal instead of retaining it at Kingston. Yet he had not considered that a political principle was involved and he thought that the ministry had been wrong in making it a government question. He felt no reluctance in continuing to recognize Baldwin’s leadership.

Cameron again represented Lanark in 1844 although life now centred on Sarnia. In the 1847 elections he ran in Kent, defeating John Hillyard Cameron, member of William Henry Draper’s Executive Council, by a large majority. When the second La Fontaine–Baldwin ministry was formed in March 1848, Malcolm Cameron became assistant commissioner of public works. He nevertheless continued his pattern of independence, and as early as May 1848 Baldwin was forced to write him a stern letter demanding his immediate presence in Montreal and an explanation of why he had not yet appeared in the assembly. The alternative, he intimated, was dismissal. Then, in April 1849, having prepared a school bill at Baldwin’s request, Cameron tabled it, in the midst of the furor over the rebellion losses bill and before informing Egerton Ryerson*, superintendent of education in Upper Canada, of its contents. Ryerson objected strongly, particularly to clauses forbidding the clergy to act as visitors in the common schools and banning the use of all books containing “controversial theological dogmas or doctrines,” a phrase which he feared could mean the exclusion of the Bible from the schools. The bill passed and Ryerson resigned. Later, however, Baldwin and Hincks, in a calmer atmosphere than had prevailed in April, reconsidered the question; in late December Ryerson was asked to continue in his post as though the act of 1849 had never existed.

Cameron’s unpredictable behaviour was not confined to politics; on one occasion while travelling with Baldwin he disappeared, and when the latter began to search, he was horrified to find his colleague stripped to the waist in an empty bar room having a thorough wash, claiming it was among the best he’d ever had. But Cameron’s reaction to annexation talk was doubtless less awkward for Baldwin. Immediately after the Annexation Manifesto was issued in October, he denounced the movement as a treasonous conspiracy “by a set of disappointed and disloyal men to dismember the Empire.”

Early in December 1849, however, Cameron resigned his cabinet seat, accusing his colleagues of not consulting him on cabinet changes, of not accepting his policies for retrenchment, and of refusing to allot funds for local improvements. He also declared that his post was a useless one. Others saw the affair differently; Baldwin stated that the first time Cameron had spoken of his resignation, he had mentioned only pressing business interests. As for retrenchment, Baldwin, La Fontaine, and James Hervey Price* all attested to the fact that Cameron had found the assistant commissioner’s salary too low. Denying the charge that Cameron had not been consulted on cabinet changes, they concluded, as did many, that his resignation was “the result of personal spleen and mortified vanity,” when he hadn’t been offered the much-desired commissionership of crown lands.

Cameron’s resignation did not remove him from the public eye. Almost immediately he began to act with a new radical faction in Upper Canada – with William McDougall* and those who were becoming known as the “Clear Grits.” He had become restive under discipline and under Baldwin’s leadership. He had also a common interest with the Grit faction. In 1840 he had felt that state support should be removed from all religions or apportioned equally to all that had a regularly constituted ministry. Now, he came out strongly for the Grit position against any church-state relationship at all. When John Wetenhall, his successor in the cabinet, presented himself for re-election in Halton in 1850, Cameron successfully championed the anti-government Grit candidate, Caleb Hopkins. With his bluff manner and hearty enjoyment of debate, Cameron assailed the new minister on numerous occasions with criticisms of the ministry, and relentlessly overpowered the mentally unbalanced Wetenhall.

Later at the founding meeting of the Toronto Anti-Clergy Reserves Association in May 1850, he moved with the support of Grit journalist James Lesslie* that the administration make the settlement of the reserves a ministerial question. The reserves and rectory lands, and the funds derived from them, should, he proposed, be devoted to education “or to such other objects of public utility as may be in accordance with the well understood wishes of the community.” The association, wishing to avoid an anti-ministerialist cast, rejected the proposal, but on it Cameron based his own position in the house. When no reference to the clergy reserves or seigneurial tenure was made in the speech from the throne in May, Cameron moved an amendment that the house regretted the omission; the motion was decisively defeated. He continued to play a prominent role as radical opposition to the ministry developed. In June he proposed that the assembly act on the clergy reserves question first and seek British sanction later. Although the motion was defeated, it and other resolutions drew the support of a large proportion of the Reform element of the Upper Canadian section of the province, demonstrating the growth of opposition in the assembly to the Baldwin–La Fontaine ministry not only from the right but also from the left.

In November 1850 Cameron announced his intention of resigning his seat. His stated reason was his wish to devote more time to business concerns, but privately he seemed disenchanted with parliamentary life. On the one hand the ministry showed no signs of dealing with the reserves, while on the other he had begun to fear that Clear Grit principles would lead to annexation. As a lumberman and a shipper he was naturally interested in expanding business opportunities, and in February 1850 he had been sent to Washington by a group of Toronto merchants in an unsuccessful attempt to interest various congressmen in reciprocity. He was utterly opposed, however, to annexation. He did not resign but he attended the 1851 session only infrequently.

By the time the Hincks–Augustin-Norbert Morin* ministry succeeded Baldwin and La Fontaine in 1851, George Brown’s Globe in Toronto had adopted an independent stance, fearing that Hincks would favour closer church-state relations in order to retain the support of the Roman Catholic Lower Canadian Reformers. Hincks needed a new organ in Toronto; McDougall of the North American saw his chance to advance Grit fortunes and a deal was made. According to McDougall, the arrangement was that two Grits, Cameron and John Rolph*, would join the ministry which would proceed with “all reasonable progressive measures”; the North American would support it, abandoning for the time being the full Grit platform. Hincks’ version differs slightly: he said he asked Rolph first but that Rolph refused to enter without Cameron; when moderate Reformer Sandfield Macdonald declined to accept the post of commissioner of crown lands an opening was available which Cameron could fill. No specific portfolio, it appears, was mentioned when Cameron agreed to take office, but he went home to Sarnia in October 1851 thinking he would become postmaster general. When details of the new cabinet were announced, however, he found himself president of the council. This office he had frequently declared superfluous, and he immediately resigned.

Cameron ran as an independent in Huron in the elections of December 1851 and won, but it is for his activities in neighbouring Kent that he is best remembered. Here Brown, supported by Alexander Mackenzie* and the Central Reform Association of Lambton, was running as an independent. In 1849–50, Brown and Mackenzie had considered the survival of the ministry essential for any Reform progress, and Cameron had aroused their enmity by resigning from it, out of, Brown maintained, bad temper. The animosity remained. Cameron thundered onto the scene in Kent hoping to achieve the same success on behalf of the ministerial candidate, Arthur Rankin, as he had for the anti-ministerial Hopkins in Halton in 1850. He promised Brown a “coon hunt on the Wabash,” circulated letters urging his friends to attend Brown’s meetings to show him what real Reformers were made of, and appealed to the local Irish to drive out the man who had so often taken anti-Catholic stands in the past. Cameron taunted Brown about changing sides and withdrawing support from the ministry, accused him of trying to split the Reform movement and of sowing discord between Catholic and Protestant, and called him a “liar” and a “political prostitute.” Brown, however, was more than able to hold his own. As to the charges of inconsistency, hadn’t Cameron himself, a leader of the Clear Grit movement, suddenly joined a ministry most of whose members he had recently opposed? Brown repeatedly outscored Cameron and won the election; “the Coon” acquired a name which stuck for years.

Although Cameron had run as an independent in the election, Hincks was still anxious to have him in the ministry. As he saw it, Cameron wanted more work for the same pay, and arrangements were made to create a bureau of agriculture and attach it to the presidency of the council. Cameron was offered the position, and in early February 1852 he accepted. Life during the sessions of 1852 and 1853 must have been uncomfortable for Cameron, who was repeatedly put in the position of voting with the ministry against principles he had previously supported. When a government proposal to increase representation within the two sections of the province came up for debate in March 1853, Brown proposed an amendment for representation by population without regard to any division between Upper and Lower Canada. Cameron voted against the amendment, and the North American explained that Grit advocacy of representation by population had referred to redistribution within the sections only. A government-sponsored school bill, passed in June 1853, enlarged the separate school rights in Upper Canada; in the voting only ten Upper Canadian members, including Cameron, supported the measure and 17 went against it. The ecclesiastical corporations question increased the discomfort of the Grit ministers: after a number of bills had been passed incorporating hospitals and charitable, religious, and educational institutions in Lower Canada, the administration introduced a general bill to cover all cases. As for the opposition, neither the Conservatives, under the leadership of MacNab, nor Brown hesitated to point out inconsistencies and to enjoy themselves at the Grit ministers’ expense. And among their Grit allies, disillusionment about Cameron and Rolph was growing; Lesslie asked Alexander Mackenzie in May 1853 if he regarded them as traitors or as men overwhelmed by influences they hadn’t anticipated.

Cameron became postmaster general in August, replacing James Morris*. As such, he automatically served on the Board of Railway Commissioners, and he was named a government director for Canada West when the Grand Trunk Railway Company was formally organized. In November 1853 he was instrumental in persuading J. R. Gemmill, publisher of the Lanark Observer, to establish the Lambton Observer and Western Advertiser (later the Sarnia Observer). During that winter Cameron was also involved in a libel suit brought on when Mackenzie insinuated in the Lambton Shield that he had attempted a shady land deal when a member of the La Fontaine–Baldwin government. Baldwin, Price, and William Hamilton Merritt*, Cameron’s colleagues in that ministry, foiled Mackenzie by declaring themselves bound by an oath of cabinet secrecy. The jury decided for Cameron, but the publicity attracted by the case did him no good.

When the elections were called for July 1854, Cameron accepted invitations to run in both South Lanark and Lambton. His campaigning was restricted to Lambton, however, where a second instalment of the “Coon chase” was taking place between himself and Brown. Brown accused Cameron of engaging in underhanded railway and land deals, using his position as postmaster general to mail election literature, holding out advantageous offers to lumbermen for staves, arranging for jobs, bringing in boatloads of French and Irish-Catholic lumbermen to swell his cheering section on nomination day (in fact opening a tavern for them), and belonging to a corrupt ministry. Cameron protested that he was being slandered, played up his role in the temperance movement, and defended the ministry, saying that it was being as progressive as circumstances permitted. Again Cameron’s temper displayed itself: at one meeting he warned Mackenzie and a friend that they would go to hell with their associates “unless they repented of their slanders against the Ministry.” In the end Cameron was defeated in both Lambton and South Lanark and was out of the assembly for over three years.

During this period Cameron appears to have withdrawn from some of his commercial enterprises. He had acted in 1853 with the Baron van Tuyll* van Serooskerken in selling lots in the Bayfield Estate in Huron County, and in 1857 he was selling town lots in Sarnia. He remained a large land owner but retired from the shipping business and appears to have sold his store. By February 1857 it was rumoured that his finances were “irretrievably embarrassed.”

When it became known that elections would be held in the late fall of 1857, Brown intimated to Mackenzie that he would run in Lambton if the Reform committee wanted him to, but suggested that they consider a local candidate. “If Cameron were only repentant & thoroughly convenanted to go for the points [of the Reform Alliance of 1857] & against the Ministry,” wrote Brown, “it would be no loss to let him in.” At Brown’s suggestion Mackenzie and Archibald Young sought out Cameron to discuss his views, but negotiations failed when tempers flared. Cameron entered the campaign in Lambton as an independent, refusing to support or condemn the moderate Conservative ministry of John A. Macdonald* and George-Étienne Cartier, and promising to judge it on its actions. An anti-ministerial candidate would also be in the fight; when it became evident Brown would not run, Hope Mackenzie was nominated. With few fundamental differences between Hope Mackenzie and Cameron other than support of the ministry, the campaign assumed a bitter personal character. Cameron was narrowly elected amid much hard feeling on all sides.

For the first year after his re-entry into the assembly Cameron voted almost consistently with the government of Macdonald and Cartier, because it was untried, he said, and should be given a chance to prove itself. When Brown proposed a resolution calling for representation by population in March 1858, Cameron voted against it, although he proposed a similar move himself in June. He then defended this apparent inconsistency by saying that he hadn’t wanted to vote a want of confidence in the ministry. Others explained it as a desire to “gratify his spleen” against Brown. In early August he voted against the short-lived Liberal ministry of Brown and Antoine-Aimé Dorion*, claiming that Brown had violated his political principles in his greed for office. It was not until March 1859 that he executed a complete volte-face, removed his support from the government of Cartier–Macdonald, and joined Brown in vigorously condemning Alexander Tilloch Galt*’s higher tariff legislation. He had earlier objected, he said, to William Cayley*’s dismissal and the increase in members’ salaries, but the new tariff had been the last straw. The Globe remarked, “There is one good thing about the member for Lambton – he never does things by halves, and having resolved to go into opposition, he took his stand accordingly.” This stand was reaffirmed in April when he spoke out strongly against government proposals for financing seigneurial reimbursements in Lower Canada.

In September 1859 the western parliamentary opposition met in Toronto to discuss future policy; it was decided that constitutional changes were necessary for the country and that a large convention should be held to consider these and to revive interest and enthusiasm for their cause: “Malcolm was there,” Brown wrote, “and behaved like a Trump. Took capital views & showed a workable spirit.” Mackenzie and the Central Reform Committee, remembering old animosities and Cameron’s erratic political record, were not so enthusiastic. They decided, however, that although they would not commit themselves for the future they would cooperate with Cameron now, “in view of the alarming state of the country.” When the Reform Convention met in November 1859, Cameron served on two committees and led off the debate. After praising the present unanimity of feeling he explained his conversion from ministerial ranks. He had always supported union, he said, but it had become unworkable and with representation by population apparently a remote possibility under the existing system, a federal scheme was the only solution. Here he looked beyond Upper and Lower Canada and advocated a platform on which other territories could enter the federation; they would be creating “the nucleus of an empire extending from the Atlantic to the Pacific.”

Cameron’s last major activity in the assembly was the chairmanship in 1860 of a select committee to consider the University of Toronto. In June of that year he was offered and accepted the Reform nomination for the Legislative Council seat for St Clair; he won by acclamation. For two and a half years in the council he continued to urge federation and expansion. He advocated the construction of railways across the continent, and in 1862 visited British Columbia. Arriving in New Westminster in August, he carried from there to Great Britain a petition of a committee, with William James Armstrong as chairman, formed by persons on the mainland who wanted their own government. He was considered an ideal delegate because of his political experience and connections, and because of his disinterestedness; however, he had already, in fact, asked the Duke of Newcastle in 1861 to remove Sir James Douglas as governor of the colony.

In 1863 Cameron was appointed queen’s printer jointly with Georges-Pascal Desbarats*, and for six years was out of politics altogether. In 1869 he surprised the people of the federal riding of Renfrew by announcing that he would run there in a by-election. He was defeated by John Lorn McDougall*, and was again defeated in the Ontario election for South Lanark in 1871 when he campaigned for an extension of the franchise and against the coalition government of Sandfield Macdonald. He tried again in the federal election of 1872 in Russell, but lost to James Alexander Grant. In 1874 he was elected as a Liberal for South Ontario over Thomas Nicholson Gibbs* and sat in the federal house for two years. He died at Ottawa on 1 June 1876, survived only by an unmarried daughter. At the time of his death he was deeply in debt. His taxes were in arrears, and he owed money to several banks, trust and loan companies, and individuals. In his last years he was a director of the Ontario and Quebec Railway and the railway linking the Marmora Iron Works to Colborne, and of the Royal Mutual Life Assurance Company, and president of the Ontario Central Railway.

Although his political career was erratic, there was one cause to which Cameron was devoted throughout his life, that of temperance. He was on the executive of many societies, including the Sons of Temperance, and introduced a number of bills on the subject in parliament. He is, however, probably best remembered as a businessman, a founder of Sarnia, and an independent and quick-tempered politician, one of the early leaders of the Clear Grit movement in Canada West.

MTCL, Baldwin papers, 35, no.107; 38, nos.5, 8, 11, 13, 24, 39–63; 54, nos.68, 69; 55, no.56; 56, no.56; 58, no.94; 61, no.91; 65, no.86; 70, no.72; 73, no.71; 78, nos.18, 19, 20; 87. PAC, MG 24, B40 (Brown papers), pp.58–60, 147, 167, 195, 202, 206, 283, 443-–44, 456, 519–20, 929–30, 1094, 1787, 1791, 1798, 1799. PAO, Charles Clarke papers, William McDougall to Clarke, 25 July 1851, 2 Feb. 1853; Mackenzie-Lindsey collection, William Spink to W. L. Mackenzie, 29 Jan. 1852; Cameron to Mackenzie, 2 April 1852; Spink to Mackenzie, 22 April 1852; Cameron to Mackenzie, 30 April 1852; Spink to Mackenzie, 7 May 1852; Cameron to Mackenzie, 10 May 1852; Thomas Webster to Mackenzie, 4 Oct. 1852; John Scott to Mackenzie, 27 Oct. 1852; James Lesslie to Mackenzie, May 1853. Queen’s University Archives, Alexander Mackenzie papers, George Brown to Mackenzie, 11 Oct. 1851, 17 March 1853, 16 April 1854, 17 Oct., 25 Nov. 1857, 29 Jan. 1858; Brown to Luther Holton, 24 Sept. 1859; Brown to Mackenzie, 28 March 1860; Mackenzie to Mary Thompson, 29 April 1876.

Canada, Province of, Legislative Assembly, Journals, 1841–60. Charles Clarke, Sixty years in Upper Canada, with autobiographical recollections (Toronto, 1908), 76–78. Francis Hincks, Reminiscences of his public life (Montreal, 1884), 252–56, 263–65, 272. Upper Canada, House of Assembly, Journals, 1836–39. Canadian Illustrated News (Montreal), 2 Oct. 1875, 213. Examiner (Toronto), 5 Dec. 1849; 13, 20 Feb., 13 March, 13 Nov. 1850. Globe (Toronto), 1 Oct. 1844; 1847–60; 2 June 1876. Lambton Observer and Western Advertiser (later Sarnia Observer and Lambton Advertiser), 1853–63; 2, 9 June 1876. North American (Toronto), 1850–52. Perth Courier (titled Bathurst Courier, 1834–57), 1834–41; 8 Nov. 1844; 30 June, 14 July, 4 Aug. 1854; 16 June, 9, 16 July 1869; 21 Oct. 1870; 6 June 1876; 7 Jan. 1943.

C. D. Allin and G. M. Jones, Annexation, preferential trade and reciprocity; an outline of the Canadian annexation movement of 1849–1850, with special reference to the questions of preferential trade and reciprocity (Toronto and London, 1912), 97, 332–33, 336–38, 345, 348. Careless, Brown; Union of the Canadas. Dent, Last forty years. Victor Lauriston, Lambton’s hundred years, 1849–1949 (Sarnia, Ont., 1949), 91–99, 224–27. J. S. McGill, A pioneer history of the county of Lanark (Toronto, 1968), 147, 156–61, 186–87, 191. Moir, Church and state in Canada West. Sissons, Ryerson, II. D. C. Thomson, Alexander Mackenzie, Clear Grit (Toronto, 1960).

Cite This Article

Margaret Coleman, “CAMERON, MALCOLM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cameron_malcolm_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cameron_malcolm_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Margaret Coleman |

| Title of Article: | CAMERON, MALCOLM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |