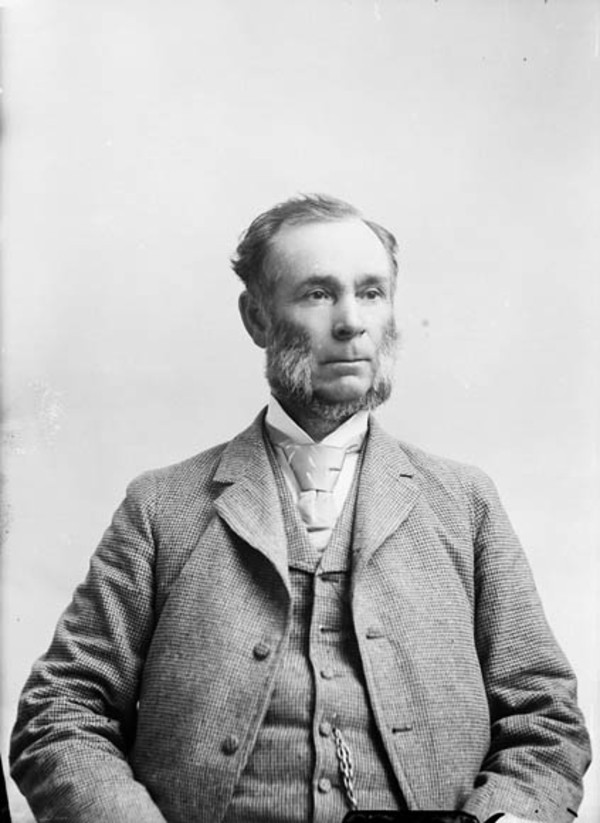

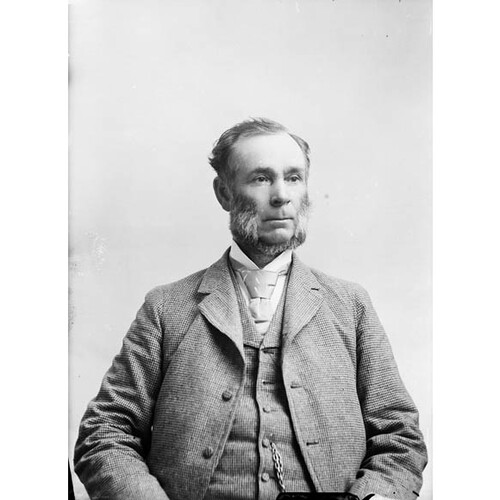

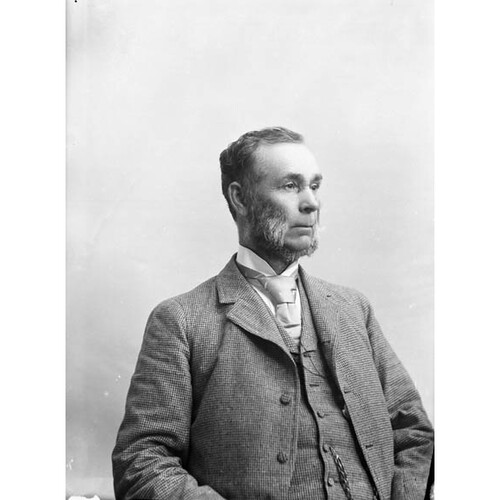

CAMERON, MALCOLM COLIN, politician, lawyer, businessman, and office holder; b. 12 April 1831 in Perth, Upper Canada; m. 30 May 1855 Jessie H. McLean, and they had eight children; d. 26 Sept. 1898 in London, Ont.

Malcolm Colin Cameron was always regarded as the son of Malcolm Cameron*, politician and businessman of the union era, who probably adopted him. He attended Knox College in Toronto, intending to join the Presbyterian ministry. However, he later chose to read law (in Renfrew), was called to the bar in 1860, and became a qc in 1876. In 1855 he had moved to Goderich, where he built a lifelong legal, business, and political career. He rose to be senior partner in Cameron, Holt, and Cameron, and invested in at least one salt-works in Huron County. (In 1865 salt had been discovered at Goderich, which quickly became the salt-manufacturing centre of Canada, in part because of its accessibility to cheap lake transport.) Beginning in 1856 he served a 12-year apprenticeship in local government, successively as councillor, reeve, and mayor of Goderich.

Cameron was elected as a Liberal to the House of Commons in 1867 for South Huron, and was re-elected in 1872 and 1874. The last victory was voided in 1875 “because of the acts of over-zealous friends.” He did not contest the subsequent by-election, at which Thomas Greenway* was returned. In 1878 Cameron was again elected for South Huron. Following the notorious electoral redistribution of 1882, he switched to West Huron, which he won that year. Narrowly defeated there in 1887, he was elected four years later only to see the result voided; he lost the 1892 by-election to Secretary of State James Colebrooke Patterson by 25 votes. Cameron took the seat back in a January 1896 by-election and held it at the general election in June. His ten campaigns over nearly 30 years were always fiercely fought and usually settled by narrow margins.

In parliament Cameron, a staunch Liberal, only occasionally showed his severely partisan side. He was most often the principled critic on a bill’s second reading, ready to move or support constructive amendments. His two constant concerns were harbours and salt. From 1867 to 1897 he argued for the development and maintenance of Goderich as a free harbour of refuge (one operated primarily for the shelter of small craft rather than as a commercial port charging fees for docking), as well as the development of nearby Bayfield as a commercial port. Largely because of his effort, the federal government spent more than $600,000 on Goderich harbour. That the work began in 1872 under Sir John A. Macdonald’s Conservative government is testimony to Cameron’s effectiveness. He also repeatedly urged the protection of Canadian lake shipping from unfair American competition.

From his first session Cameron called for the protection of Canadian salt against cheaper salt imported from Britain and the United States. He was conscious of the conflict between liberalism and protectionism, but in 1870, citing John Stuart Mill, he defended retaliatory tariffs: “Salt stood in a particular position from the wealth of the manufacturers who had resolved to crush the infant manufacture of Canada.” He called for a “national policy and protection of native industry,” with Liberal leader Alexander Mackenzie interjecting “No.” During the 1879 budget debate Cameron strove to get in line with party policy, claiming that “he was opposed to the tariff, though he was at one time a Protectionist himself.” None the less, when the budget moved to the ways and means committee, he asked why the salt industry had been “left out in the cold. . . . Our salt interest alone had received no encouragement, no assistance, and no consideration.” He wrung from Finance Minister Samuel Leonard Tilley a promise to consider ways of helping Canadian salt manufacturers. In 1897 Cameron pressed the newly elected Liberal government of Wilfrid Laurier* to impose a tax on American and British salt, but he still maintained that “this is not protection in the ordinary sense of the word, as hon. gentlemen opposite understand it.” On no other issue did his views come so sharply into conflict with those of his party.

The west was the major new interest to emerge during Cameron’s parliamentary career. In 1880–83 he made regular summer trips to Manitoba and the northwest. Macdonald alternately teased and goaded him for his well-known private interest in western lands; in 1885 he accused Cameron of speculating in Métis scrip. In attacks on the government, commencing in 1880, Cameron took particular aim at Indian Affairs (a department under Macdonald from 1878 to 1887). He focused on the waste and corruption that retarded settlement: dominion land guides got settlers lost, land speculation around Regina hindered settlement, the administrative costs of Indian Affairs and the North-West Mounted Police were excessive, and crown land was being sold privately. Aware of agitation in the northwest, he moved a private bill in 1884 and again early in 1885 to provide elected representation for the territories in the commons, but without success. In the 1887 election his charges against Indian Affairs led to a campaign against him, including a government pamphlet to refute his allegations.

Re-elected in 1896 in the midst of debate over federal remedial legislation for Roman Catholic schools in Manitoba, Cameron made only one brief speech, opposing coercion of the province and claiming more could be obtained for the Catholic minority through compromise. The remedial bill he called hypocritical since it was opposed by the Orange lodge yet the government had in the lodge one of the “principal elements” of its strength. Cameron had earlier opposed a federal charter for the lodge and denounced the hanging of Louis Riel* as mere revenge for the death of “Brother” Thomas Scott*.

As prime minister, Laurier found Cameron’s protectionist leanings and his continued, inveterate campaign against the administration of Indian Affairs and the NWMP embarrassing. Still, his interest in the west made him an obvious candidate for the lieutenant governorship of the North-West Territories, into which office he was sworn on 7 June 1898. Less than three months later he took a leave of absence for reasons of health and returned to Ontario. He died at his son-in-law’s house in London on 26 September at the age of 67.

Cameron’s career illustrates the tensions of a Liberal in an era of Conservative dominance. He found it difficult to reconcile tangible personal and local interests with the demands of a party only just coming into being. Perennially in opposition, after the 1896 election he could not adjust to a new role as a member of government. Although a contemporary Goderich journalist, Daniel McGillicuddy, claimed that Cameron had “reduced invective to a science,” his parliamentary career was one of constructive critical opposition.

NA, MG 26, A, T. Greenway to Macdonald, 7 Aug., 17 Sept. 1872; 29 April, 18 Nov. 1874. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1868–97. Globe, 27 Sept. 1898. Manitoba Morning Free Press, 27 Sept. 1898. Winnipeg Daily Tribune, 26 Sept. 1898. Canadian biog. dict. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898), 144. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. Dianne Newell, Technology on the frontier: mining in old Ontario (Vancouver, 1986), 138. Swainson, “Personnel of politics.” Dan McGillicuddy, “M. C. Cameron, as I knew him: a character sketch,” Canadian Magazine, 12 (November 1898–April 1899): 57–60.

Cite This Article

Peter A. Russell, “CAMERON, MALCOLM COLIN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cameron_malcolm_colin_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cameron_malcolm_colin_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter A. Russell |

| Title of Article: | CAMERON, MALCOLM COLIN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |