Source: Link

SCOTT, THOMAS, adventurer; b. c. 1842, probably at Clandeboye, County Down (Northern Ireland); d. 4 March 1870 at Red River (Man.).

Almost nothing is known of the early life of Thomas Scott, whose death during the Red River disturbance of 1869–70 provoked a storm of English-French hostility in central Canada. His youth was spent in Ireland. According to Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*], when governor general of Canada, Scott “came of very decent people – his parents are at this moment [1874] tenant farmers on my estate in the neighbourhood of Clandeboye – but he himself seems to have been a violent and boisterous man such as are often found in the North of Ireland.”

About 1863 Scott turned up in Canada West, where he was probably a labourer. He was a Presbyterian, an active and zealous Orangeman, and a member of the 49th Hastings Battalion of Rifles at Stirling. In the summer of 1869 Scott arrived at Red River and found employment as a labourer on the “Dawson Road” project, a new wagon road connecting Red River to Lake Superior, under Superintendent John Allan Snow* [see Simon James Dawson*]. In August he led a strike against Snow, who wisely capitulated after Scott threatened to throw him into the Seine River near Red River. However, the disgruntled superintendent laid a charge of aggravated assault against Scott and three of his cohorts at the autumn session of the General Quarterly Court of Assiniboia. Scott was convicted and fined £4 in November. Now out of work, he drifted around Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg) and fell under the influence of John Christian Schultz*, leader of the Canadian party, a small Anglophone group which promoted the annexation of Red River to Canada. From this point on, Thomas Scott was caught up in the struggle for the future of the Red River Settlement.

By allying himself with Schultz’s group in the early winter of 1869–70, Scott may have found kindred spirits but he had chosen the losing side. Louis Riel* and the Métis were in effective control of the settlement. An abortive resistance by the Canadian party resulted in the capture on 7 December of Schultz, Scott, Charles Mair*, and 53 others and their incarceration in Upper Fort Garry. Scott was an unexceptional prisoner until the night of 9 Jan. 1870 when he, Mair, and several others managed to escape. Scott fled to the Canadian enclave at Portage la Prairie bearing lurid tales of the treatment meted out by his captors. During the next month he helped to organize a relief expedition of Canadians, ostensibly to secure the release of the remaining prisoners and with a secondary objective of attempting to capture Riel. The latter, meanwhile, had released all the prisoners, as he had promised Donald Alexander Smith*, the emissary from Ottawa.

Scott and the Portage party descended on the Red River Settlement in mid February and tried to enlist the aid of the Kildonan settlers, but without success. Except for the irreconcilables among the Canadians, the people of Red River were prepared to allow Riel’s provisional government, which would be broadly representative, to effect a settlement with Ottawa. A concilatory message from Riel to the Kildonan settlers ended the threat and the opposition melted away.

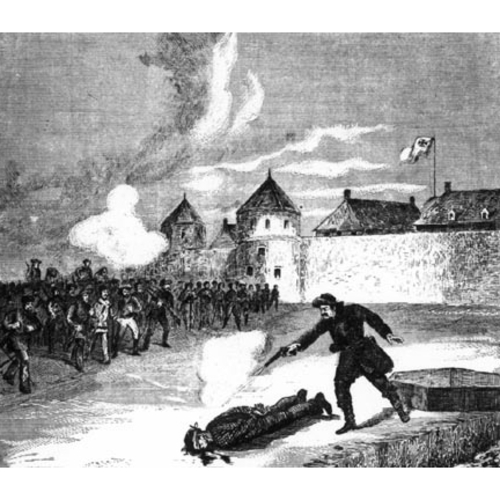

With little alternative but to return to Portage, Scott and his group decided on a last defiant gesture, to pass through Winnipeg under the very walls of Upper Fort Garry where Riel and his Métis followers were established. Unaware that the challenge to the provisional government had dissipated, Riel himself probably ordered the capture of the Portage group, which was accomplished without violence on 18 Feb. 1870. Thomas Scott and 47 others, including Major Charles Arkoll Boulton*, their presumed leader, were confined in the fort. Almost immediately a Métis court martial decided to execute Boulton, but Riel was persuaded to spare his life in return for a promise from Smith that he would do all in his power to evoke support for the provisional government.

Outside the walls of Upper Fort Garry the emergency seemed to be over. But inside Thomas Scott was proving a difficult prisoner. Although the evidence is not completely conclusive, it seems clear that Scott did not disguise his contempt for the Métis. He so insulted and provoked his guards that on 28 February they dragged him outdoors and beat him. The incident marked a tragic turning point.

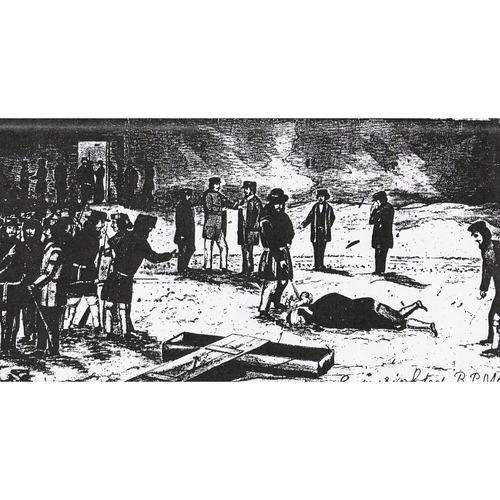

Though there was acquiescence, if not enthusiasm, among most of the inhabitants of Red River in allowing Riel and the incoming provisional government to negotiate entry into confederation with Ottawa, Riel’s leadership depended in the end on the continuing support of the armed Métis. After months of tension and threatened attack by the Canadian party, they were excitable and unruly. The reprieve of Boulton could be interpreted as magnanimity based on strength. To ignore Scott’s challenge might be seen as weakness. There was a growing spirit among the Métis that Scott must be punished. A Métis court martial, an ad hoc tribunal employed frequently on the prairie, met on the evening of 3 March; its members included Ambroise-Dydime* and Jean-Baptiste Lépine*, André Nault*, and Elzéar Goulet. Scott was tried on the charge of insubordination. By majority vote the court martial convicted him and the death penalty was invoked. The following day he was shot by a Métis firing squad.

In the long run the execution of Scott was a blunder. It jeopardized the entry of the Hudson’s Bay territory into the dominion, poisoned relations between English and French Canadians, condemned Riel to the same fate 15 years later, and bedevilled the future development of Manitoba. In justifying his action, Riel explained to Smith that “We must make Canada respect us.” Such respect depended on his abilty to control the local situation and, moreover, to demonstrate that control. We may accurately describe the action as mistaken, but only from hindsight.

Scott, an obscure if volatile figure during his life, became a cause célèbre after death. To a degree quite unconnected with his own tragic fate, he came to symbolize one of the unresolved problems of the new confederation. Was the Northwest to be the patrimony of Ontario or was its settlement to be a joint venture of English and French Canadians? The more extreme reaction may be seen in a resolution of Toronto Orangemen carried by the Globe on 13 April 1870: “Whereas Brother Thomas Scott, a member of our Order was cruelly murdered by the enemies of our Queen, country and religion, therefore be it resolved that . . . we, the members of L.O.L. No.404 call upon the Government to avenge his death, pledging ourselves to assist in rescuing Red River Territory from those who have turned it over to Popery, and bring to justice the murderers of our countrymen.” Thomas Scott thus became a martyr in the cause of Ontario expansion westward, a sentiment implicit even in the pathetic letter of his brother, Hugh Scott, to Sir John Alexander Macdonald*: “my brother was a very quiet and inoffensive young man, but yet when principle and loyalty to his Queen and Country were at stake throughout a brave and loyal man.”

PAC, MG 26, A, 14, 102; MG 27, I, A4; MG 29, E34. PAM, MG 2, B4; C14, 412, 417, 446; MG 3, B17; D1, 616, 619, 629; MG 7, C12, p.7; MG 12, A; B, Ketcheson coll., correspondence, pp.55, 57, 116, 135; telegram book, no.1, 118; Lieutenant-governor’s coll., letterbooks, M, 36, 40. PRO, CO 42/685 (mfm. at PAC). Begg, Red River journal (Morton). Can., House of Commons, Report of the select committee on the causes of the difficulties in the North-West Territory in 1869–70 (Ottawa, 1874). Dufferin-Carnarvon correspondence (de Kiewiet and Underhill). “Letter of Louis Riel and Ambroise Lépine to Lieutenant-Governor Morris, January 3, 1873,” trans. and ed. A.-H. de Trémaudan, CHR, VII (1926), 137–60. Manitoba: the birth of a province, ed. W. L. Morton (Altona, Man., 1965). Preliminary investigation and trial of Ambroise D. Lepine for the murder of Thomas Scott . . . , comp. [G. B.] Elliott and [E. F. T.] Brokovski ([Montreal], 1874). [Louis Riel], “The execution of Thomas Scott,” ed. A.-H. de Trémaudan, CHR, VI (1925), 222–36. Alexander Begg, The creation of Manitoba; or, a history of the Red River troubles (Toronto, 1871). A. S. Morton, History of the Canadian west. W. L. Morton, Man.: a history (1957). J. H. O’Donnell, Manitoba as I saw it from 1869 to date, with flash-lights on the first Riel rebellion (Winnipeg and Toronto, 1909), 40. Stanley, Louis Riel.

Cite This Article

J. E. Rea, “SCOTT, THOMAS (d. 1870),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 31, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/scott_thomas_1870_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/scott_thomas_1870_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. E. Rea |

| Title of Article: | SCOTT, THOMAS (d. 1870) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | January 31, 2026 |