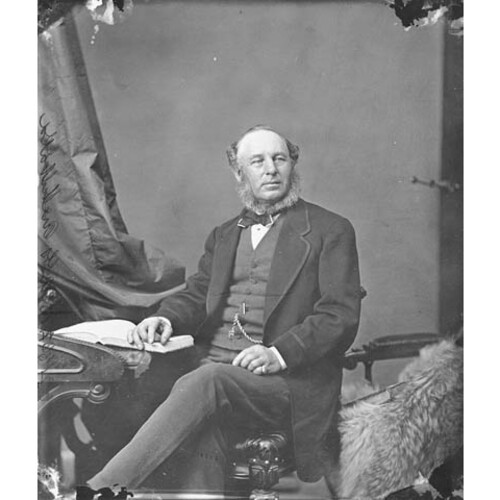

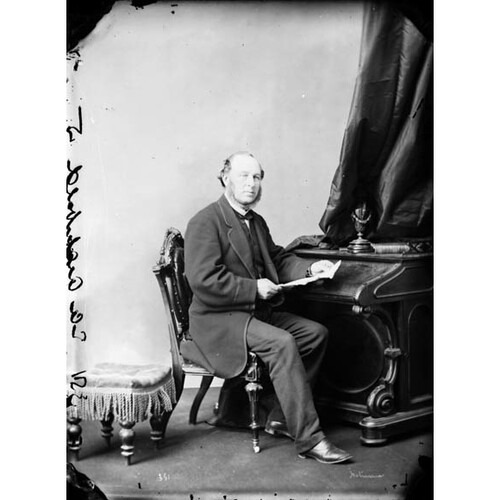

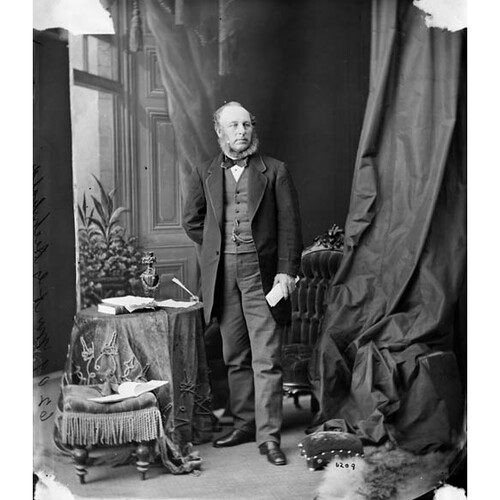

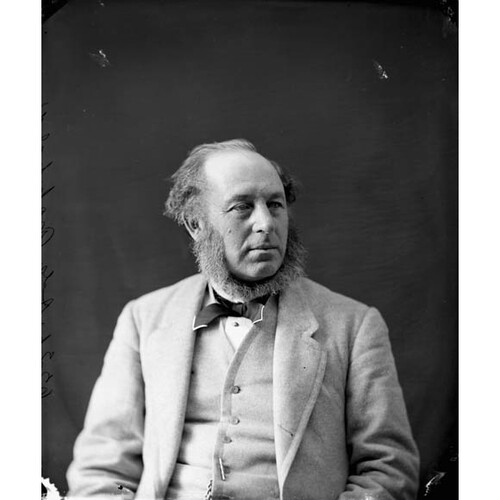

ARCHIBALD, Sir ADAMS GEORGE, lawyer, jp, office holder, politician, and judge; b. 3 May 1814 in Truro, N.S., second son of Samuel Archibald and Elizabeth Archibald; m. there 1 June 1843 Elizabeth Archibald Burnyeat, and they had one son, who died at age 14, and three daughters; d. there 14 Dec. 1892.

Adams George Archibald started his education with a relative in Truro and later studied under Thomas McCulloch* at Pictou Academy. He had some ability for science and spent a summer exploring the Bay of Fundy with McCulloch. He began studying medicine in Halifax under Dr Edward Carritt, but, dissatisfied with that profession, he became a pupil of William Sutherland, a leading barrister in the city. Archibald was commissioned as a notary public in 1836 and as an attorney in 1838. He was called to the bar of Prince Edward Island in June of that year and to the Nova Scotia bar seven months later. Perhaps as early as 1836 Archibald had opened an office, not in Halifax but in Truro, where he could benefit from his extensive family connections. To promote his legal work he deliberately sought public office. He became in turn a justice of the peace (1836), commissioner of schools (1841), and registrar (1842) and then judge (1848) of probate for Colchester County. In 1849 he was appointed one of five commissioners to oversee the construction of an electric telegraph from Halifax to the New Brunswick border [see Frederic Newton Gisborne].

In 1843 Archibald had married Elizabeth Burnyeat, his cousin and the daughter of the Anglican minister of St John’s, Truro. They lived in John Burnyeat’s former home, Longfield Cottage. Archibald was a firm Presbyterian, but two of his daughters married Anglican clergymen.

Although an active supporter of the Reform, or Liberal, party, he waited until his financial position was secure before he sought elected office. In the general election of August 1851 he ran as one of two Reform candidates for Colchester County. Six members of the Archibald family had previously sat in the House of Assembly, and the family had long been prominent politically, economically, and socially. The Conservative opposition tried to exploit any resentment against the family’s domination in the county by pointing out that its hold would be strengthened should Archibald be elected. He led the polls in the election, but the early expectation that he would have a rapid political advancement did not materialize. In his speeches in the assembly he avoided the flamboyance and the rhetorical flourishes popular at the time, dismissing them as mere appeals to sentimentality. Instead, in a barely audible voice, he would try to build cogent, well-structured arguments. His true strength lay in the committees, where most of the business of the house was conducted.

Archibald strove to gain consensus on issues, yet once he had decided on a particular policy he tended to disregard the political consequences. Firmly believing that the government should be controlled by the people, he nevertheless opposed any change from the old 40-shilling freehold provision for enfranchisement, including that introduced by his own party in 1851. He was particularly against the successful attempt to introduce universal male suffrage, made in 1854 by Conservative leader James William Johnston*, who argued that it was necessary in order to counteract the corrupting influence of ministerial government. Archibald’s dislike for tampering with established British procedure was also evident in his opposition to Johnston’s suggestion to balance universal male suffrage with an elective upper house based on a prohibitive franchise of £1,000 real property. However, he was one of the few Liberals in the assembly who supported Johnston’s proposals to introduce elected municipal government in the province and to restrict the role of the magistrates, who were appointed by the cabinet. Archibald had no objection to limiting the power of the executive (Johnston’s primary objective), provided that respectable, responsible elements continued to play their role in society.

In response to any call for political change, Archibald would suggest that it must wait until the economic and moral development of the people had improved sufficiently for them to benefit from it. The first step should be the introduction of state schools. In 1853, in an attempt to raise the money for such a system, Archibald and a few colleagues had tried unsuccessfully to have the legislature implement the necessary taxation. The following year, however, it established a normal school in Truro, and Archibald was named one of the school’s directors.

According to Archibald the second step should be to increase trade with the United States, and in 1852 he had advocated reciprocity with that country. When an agreement worked out in Washington between the United States and the British North American colonies was brought before the assembly for ratification late in 1854, he gave it his full support. Unlike Joseph Howe* and some other Liberals, he felt the fact that Nova Scotia had been inadvertently excluded from the negotiations was not sufficient justification to forgo the benefits of the agreement. Archibald’s desire for enhanced trade led him to support railway construction in the province. Throughout the extended debate, which began in 1851 with a proposal to build a line to Windsor, he contended that the need for railways far outweighed the question of whether they should be built and operated as private or as public projects. He thus differed with Howe in 1854 when the latter insisted that all railways should be built by the government.

Archibald also argued in favour of economic development through the exploitation of natural resources, but he personally did not invest in any project involving industrial development. Instead he put his money in mortgages, especially in the agricultural region of Colchester County, which was the centre of his political strength. This fact does not necessarily reflect a dichotomy in his thinking between a rural society and an industrial one, but rather that he had only a vague concept of industrialization and the social changes it would bring. He assumed that human progress would follow resource development. In 1852, as chairman of a house committee on mines and minerals, he sought to break the control of provincial coalfields enjoyed by the General Mining Association since 1827, and three years later he called for immediate negotiations with the British government to end a monopoly which, he declared, had retarded trade and injured provincial revenues. Negotiations undertaken by Premier William Young* with the British government in 1856 were unsuccessful. The following year the new premier, Conservative J. W. Johnston, who wanted bipartisan support but refused to work with Young, invited Archibald to join him in another attempt. They reached a settlement in England, but only at the cost of agreeing to the maintenance of the company’s monopoly for 25 years and a substantial reduction in provincial royalties.

Archibald’s own political career had taken a step forward with his appointment as solicitor general on 14 Aug. 1856. However, his term was cut short by the resignation of the Young ministry the following February after a defeat in the assembly that in large measure evolved from a sectarian quarrel over the dismissal of William Condon, a minor government employee and president of the Charitable Irish Society, on charges of treason [see William Alexander Henry*]. This affair set the tone of political debate for the next two years as well as for the general election in 1859. Archibald and fellow Liberal Alexander Campbell were elected in Colchester South after a contest marked by bribery and violence. The Liberals emerged with 29 seats to 26 for the Conservatives, who challenged the election of some Liberals because they held minor government offices. Nevertheless the Johnston ministry was defeated on a want of confidence motion and a Liberal government assumed office with Archibald as attorney general. His subsequent victory in the necessary by-election was immediately disputed on grounds of corruption, and a committee of the house, composed of six Conservatives and one Liberal, voted for his expulsion. The Liberal-controlled assembly refused to accept the recommendation.

Although the Liberal ministry survived, the tumultuous and vicious debates obstructed the business of the house. None the less, Howe, who became premier in August 1860, continued his efforts to build an intercolonial railway. In September the following year Archibald and railway commissioner Jonathan McCully* accompanied him to Quebec to meet with representatives of the Canadian and New Brunswick governments and formulate a proposal to present to the British government. Despite early signs of progress, the project collapsed. Falling government revenues, especially in 1862, made it impossible for the provincial government to undertake any further railway expenditures out of its own resources. Archibald, however, remained convinced that the railway was essential for the economic development of the province.

Following Howe’s appointment as imperial fisheries commissioner in December 1862, Archibald was recognized as party leader, although Howe would remain premier until after the general election of May 1863. That year Archibald’s distaste for universal male suffrage led him to introduce a bill to reinstate a property qualification for the franchise. The Legislative Council would agree to the measure only if it were to come into operation after the general election. It was later seen by some, including Howe, as a major reason for the disastrous defeat suffered by the Liberals. Archibald was one of only 14 Liberals elected.

When the legislature met in February 1864 the new, Conservative government had a solid majority, and the economy and provincial revenues were improving rapidly. Charles Tupper*, the provincial secretary, who soon replaced Johnston as premier, was determined to make his mark by establishing a free school system based on compulsory assessment. Archibald supported these measures, but he strenuously objected to the provision that made the Executive Council the Council of Public Instruction on the grounds that politics should be kept out of education in the interest of social harmony.

In August Tupper asked Archibald and McCully to be the Liberal representatives at an intercolonial conference to be held at Charlottetown in September. Archibald had not previously shown any enthusiasm for either a maritime union or a larger colonial union, but his views changed markedly following the Charlottetown meeting and the one held at Quebec in October. He may have been influenced by a belief that it was the only way to obtain a rail link with the Canadas, but of greater weight, perhaps, was a certain weariness with provincial politics and the desire for a broader vision. He may also have come to a belated realization that the changing relationship of the colonies with Great Britain during the preceding 20 years required a readjustment in the relationship between the colonies themselves.

During the drawing up of the proposed constitution in Quebec, Archibald’s instinctive preference was for a legislative rather than a federal union, perhaps because the former was identified with Great Britain and the latter tainted with republicanism. Within the British model there was a strong tradition of localism, and perhaps for this reason he insisted that if the provincial legislatures were retained, there should be no alteration in their form. But his real strength lay in practical affairs, especially in the financial terms of union. Later, in Halifax, it was Archibald who had the difficult task of justifying these provisions.

As the opposition to union in Nova Scotia developed during the winter of 1864–65, Archibald was the sole Liberal in the assembly to support it. Tupper may well have welcomed this advocacy by the leader of the Liberals as speeding a break-up of the party, but the only real effort to supplant him, led by William Annand* in 1866, was unsuccessful. It was certainly not the first time that Archibald had broken with his party on an important public issue.

Following the legislature’s acceptance of the principles of union in 1866, Archibald was named as one of six Nova Scotian delegates to the London conference that was to arrange the final terms. Indicative of Archibald’s support for confederation is the fact that he apparently did not object to the financial terms, even though they were quite disadvantageous to Nova Scotia. During the debate on confederation in the last session of the legislature before union, he argued that favourable concessions had to be made to the Maritime provinces and that they would always be able to claim further concessions in the new dominion. In recognition of his contribution to the cause of union, in 1867 he was appointed secretary of state for the provinces in the first federal cabinet, that of Conservative Sir John A. Macdonald.

As soon as the legislature in Halifax finished its last session, Archibald returned to Colchester County to prepare for the September general election to the federal house. His confidence that resistance to confederation would crumble now that it was law was not entirely misplaced: some avowed anti-confederates indicated that if elected they would support union. But his belief that the confederates would carry at least half of the seats completely ignored the strength of antagonism in the province and the determination of the anti-confederates to defeat him. He spent money so freely that Catholic archbishop Thomas Louis Connolly* of Halifax was convinced the election had brought Archibald to the edge of bankruptcy. Despite his efforts the anti-confederate attack was successful and Tupper was the sole confederate elected in the province.

Macdonald persuaded Archibald to remain in office until he could use the portfolio to attract an anti-confederate. But when it became apparent that opposition to union in the province was increasing, Archibald resisted further pleas and resigned on 30 April 1868. He played little part in securing “better terms” for Nova Scotia [see Howe], but did manage a modest recovery by winning a federal by-election in Colchester in 1869.

Although Archibald did not like Ottawa, he had time to improve his French and to indulge his taste for reading. In May 1870, during the debate on the Manitoba Bill, he defended the government and called for a conciliatory policy towards the people of the Red River region. His speech appealed to Sir George-Étienne Cartier*, who, in the absence of the seriously ill Macdonald, asked him to be the first lieutenant governor of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. Archibald had no real interest in the affairs of the northwest, but his sense of public duty overcame his reluctance and he agreed to serve for one year, on condition that he receive a seat on the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia at the end of his term.

Archibald’s appointment provoked comments in the Montreal papers that a respectable nonentity from the Maritimes had been selected to serve as an arbiter between the interests of Quebec and Ontario. The Ontario press, especially the Liberal newspapers, criticized the appointment on the grounds that a period of military rule was first necessary for the establishment of law and order. Some papers even concluded that the move was part of a Quebec conspiracy to prevent the dispatch of any military expedition to Manitoba. Thus, weeks before he arrived in Manitoba, Archibald was seen as a tool of Cartier, who through a policy of appeasement would prevent the establishment of law and order in Manitoba after the uprising of 1869–70 [see Louis Riel*]. Although the Macdonald government did not believe that a period of military government was necessary, not all members of the cabinet accepted Cartier’s approach and some probably viewed Archibald with suspicion.

In August 1870, in a meeting with Governor General Sir John Young* at Niagara Falls, Archibald was sworn into office. He then travelled west to Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg), where he found that Colonel Garnet Joseph Wolseley*, the leader of the military expedition sent to the area, had arrived before him and appointed Donald Alexander Smith* as acting governor of Assiniboia to preserve the appearance of civilian government in the province.

Archibald proclaimed the new government of Manitoba on 6 September, but he had difficulty finding suitable candidates to sit on his council. The natural leaders among the Métis had nearly all been implicated in the uprising. The degree of antagonism toward them was clearly illustrated on 13 September when Elzéar Goulet*, a member of the court martial that had condemned Thomas Scott*, drowned in the Red River while attempting to escape from pursuers. This incident involved soldiers from the 1st (Ontario) Battalion of Rifles, who until their withdrawal in June 1871 willingly took part in attacks on the Métis. The identity of those soldiers involved was well known, yet local pressure prevented any charges from being laid. Archibald resisted repeated demands that he issue warrants for the arrest of Riel and other Métis leaders, but his attempts at reconciliation were badly compromised by the failure of the British government to issue an amnesty for those involved in the rebellion.

Although hostility in the province to the Métis obviously restricted Archibald’s choice, there is no indication on the other hand that he wanted to work with the leaders among the group that had opposed the Métis in 1869–70. Certainly he had no intention of including in his ministry John Christian Schultz, whom he viewed as the major instigator of trouble in Manitoba. For almost his entire term in the province, Archibald was convinced that he could isolate Schultz and destroy his influence. In this Archibald seriously underestimated the man. Compelled to restrict himself to a bare minimum of ministers, Archibald appointed Marc-Amable Girard as provincial treasurer and Alfred Boyd*, a merchant, as provincial secretary. Although these choices had the appearance of balancing the two ethnic elements, they actually favoured the English-speaking community because Boyd had been an opponent of the provisional government and Girard was a newcomer recently arrived from Quebec. Yet Archibald’s actions earned him little support from the province’s anglophones. One of his priorities was the establishment of a provincial legislature. Before an election could be held, he had first to arrange for a census of the population. When it was completed in December 1870, he was able to settle the boundaries of the 24 electoral divisions stipulated in the Manitoba Act of 1870. Archibald was undoubtedly pleased that a number of the candidates elected that month were moderates in sympathy with his own views on reconciliation, but he could not ignore the fact that Smith’s defeat of Schultz in Winnipeg and St John resulted in a riot by the members of the Ontario rifles. Moreover, among the Métis only those who had kept a low profile in the uprising had been willing to stand, and even some of them were not safe from attack on the streets of Winnipeg.

After the election Archibald in January 1871 added two men from Quebec, Henry Joseph Clarke* and Thomas Howard, to his Executive Council as attorney general and minister without portfolio respectively. Representation of the Métis in the government was achieved with the appointment of fur trader James McKay*. Since he did not have a seat in the assembly, a place was found for him in the Legislative Council, which Archibald, in accordance with the Manitoba Act, organized in March. Archibald’s expectations that his ministry would become an effective force in the province were soon shaken. It failed to provide leadership and did not develop any cohesion; various members, such as Clarke, followed highly eccentric, individualistic courses. Archibald, therefore, continued to be the real leader of the government. Calling on his Nova Scotian experience he provided his ministry with 31 proposals for such basic services as court and school systems. He managed to get his measures through the session, which began on 15 March, but he reserved four acts intended to promote railway construction. He also had considerable difficulty over Clarke’s insistence that lawyers be admitted to Manitoba only with the consent of the attorney general.

There was also work to be done in preparation for the expected influx of settlers, particularly in the dispersal of the crown lands. With the completion of the census in December, Archibald had been able to prepare a lengthy memorandum for the federal cabinet, in which he presented an overview of the land resources and population of Manitoba as well as of existing commitments that affected land held by the province. He assumed that any land grants would be surveyed rectangularly according to the system used in the United States. In advocating that land should be granted in blocks of 160 acres he explicitly ignored the system of common lands followed by the Métis.

Archibald had no wish to preserve the traditional way of life of the Red River area. Indeed, he saw the problems in Manitoba as a clash between a primitive, isolated society and an advanced civilization. The people of the northwest, he had told Sir William Young in July 1870, were but children, with the wilfulness and imagination of children, and must be persuaded to adapt to progress. His continued call for conciliation thus reflected both his sense of public morality and a strong desire to bring about the inevitable transition without further violence.

Archibald none the less remained acutely aware of the possibility that frustrated and angry Métis might well resort to violence. A continuing source of grievance was the question of amnesty, over which he had no control. Nor did he have the authority to distribute the 1,400,000 acres promised the Métis in the Manitoba Act. However, he decided to intervene in July 1871 when a group of Métis complained that while they had been on the plains, settlers from Ontario had staked out claims by the Rivière aux Îlets-de-Bois, which they renamed the Boyne River. Their claims posed a direct challenge to the Métis system of common lands, and their new name for the area emphasized the religious and ethnic nature of the confrontation. Sensitive to the seriousness of the provocation, Archibald attempted to make the Métis aware of the folly of offering any resistance to the settlers. At the same time he advised them to file claims to consolidate their existing communities. He was convinced that they would soon sell off their land scrip to settlers who would be better able to exploit the land. His strategy was designed to placate the Métis in the short term without interfering with the long-term objectives of the federal government. Unfortunately he exceeded his mandate and contradicted a recent policy of the federal government that allowed Ontario settlers to stake claims on unsurveyed lands. He was curtly rebuked by Joseph Howe, secretary of state for the provinces, and Macdonald was unwilling to give serious consideration to Archibald’s opinion. Macdonald may well have been influenced by fears about the Orange vote in Ontario. At the same time he gave no indication of any understanding of or sympathy for the Métis. The incident of the Rivière aux Îlets-de-Bois thus weakened Archibald’s position in Ottawa, aggravated the federal government’s grievance against the Métis, and fed the deeply held conviction of the Métis that they had been betrayed by Ottawa.

By the fall of 1871 Archibald was becoming more and more concerned over reports that Fenians were preparing to invade Manitoba. Since the withdrawal of the Ontario and Quebec rifles in June, Archibald had been forced to rely on approximately 100 militiamen and 70 police constables for the defence of the province. Moreover, he was well aware that the Métis might join any invaders. His request for troops was rejected by Macdonald as an unnecessary expense, until William Bernard O’Donoghue* actually led his small band into Manitoba in October. The raid was a short-lived affair and within a week it had collapsed. O’Donoghue himself was captured by two Métis. Before they were aware of his capture, a council of Métis leaders had decided to take up arms against him. Riel, with the obvious intent of gathering political support, invited Archibald to meet them at St Boniface. In spite of the fact that he must have known it would cause trouble, Archibald shook hands with a number of the leaders, including Riel himself, though no names were given at the meeting.

In Ottawa, Macdonald became convinced that the incidents of the summer and fall of 1871 were part of a conspiracy initiated by Roman Catholic priests who refused to accept Canadian authority. On 25 November Archibald sent in his resignation in order, he said, to give the government a free hand in dealing with the controversy that had developed over his actions. In a private letter, however, he informed Macdonald that the prime minister’s rejection of his conduct reflected a complete lack of understanding of the situation in Manitoba. He went on to read Macdonald a lesson in constitutional procedure. In the tradition of localism he argued that his policies were approved by the majority of residents in the province and according to the principles of self-government their views should be his sole guide. He spiritedly defended his actions in the speech from the throne at the opening of the Manitoba legislature in January 1872. When it passed with an overwhelming majority, he sent in a second and more formal notice of his resignation.

Macdonald had considerable difficulty in finding a replacement for Archibald, who was asked to withdraw his resignation. He agreed to remain until after the forthcoming federal election, but since the tensions in the province were unresolved, he felt that he was in an anomalous position. When problems developed, such as those involving Indian treaties nos.1 and 2, which he had helped negotiate in August 1871, he acted as decisively as possible. The difficulties arose in part from complaints of native leaders that promises of farm supplies made by Indian Commissioner Wemyss McKenzie Simpson had not been kept. A more pressing problem occurred when eastern merchants, refusing to accept Treaty No.2, proceeded to cut timber on lands reserved for the Ojibwas. As lieutenant governor of the North-West Territories, Archibald also had to deal with unrest among the Indians and in some Métis settlements in that region. However, he had little power and few resources to deal with the situation.

The federal election in September 1872 brought additional difficulties, including an attack on the polling station in St Boniface. What attracted particular attention outside the province, however, was the election in Provencher of Cartier (who had been defeated in Montreal East) in the place of Riel. Macdonald had instructed Archibald that under no circumstances should Riel be allowed to stand down in Cartier’s favour, but Archibald, who was convinced that he understood the province better than Macdonald, made little effort to carry out these instructions. When Archibald was finally given permission to return to Ottawa in October, his departure was officially regarded as temporary, but it was widely understood that he would not return. For his work in Manitoba he was made a cmg.

Various complications delayed his appointment to the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia, and in February 1873 he agreed to become a director of the Canada Pacific Railway Company. He travelled to England with John Joseph Caldwell Abbott and Sir Hugh Allan* to arrange financing for the proposed railway. Archibald apparently felt that there was little possibility of success but was determined to explore every lead, in order to prevent Allan from blaming any failure on the government. On his return Archibald found that his judicial appointment had gone through. He remained on the railway board but had no further involvement with its affairs because of Abbott’s determination to operate the company without representatives from the “outlying provinces.”

After the appointment of J. W. Johnston as lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia in June, Archibald was made judge in equity, but within days he was invited to become lieutenant governor when Johnston withdrew his acceptance because of ill health. Archibald resigned from the bench and was sworn in on 5 July. The position he assumed as lieutenant governor in Nova Scotia was considerably easier than that in Manitoba. Yet proceedings in the Nova Scotia assembly in the 1870s were as raucous as any in the history of the province. He had also to deal with ministers who resented his part in confederation.

The role of the lieutenant governor had been altered by the act of union and by the federal government’s attempt to make the office holder its agent. A major limitation on Archibald’s power was that provincial officials usually communicated directly with federal officials without going through his office. Further, provincial legislation considered contrary to federal policy, especially with respect to trade and commerce, was likely, under both Macdonald and Alexander Mackenzie, to be disallowed by the federal government rather than reserved by the lieutenant governor. Archibald did use his power to reserve two bills and refused to sign six others.

Sir Charles Hastings Doyle*, who had been lieutenant governor from 1867 to 1873, had had little interest in local affairs and in 1871 had ceased to attend council meetings. Archibald, as a former attorney general, was better able to evaluate the state of public measures. Moreover, his experience in Manitoba may well have influenced his views on his function. On first taking office he participated in meetings of the cabinet, but he did not continue this practice after 1874. Indeed, by 1876 he had abandoned any overt political role and preferred to remain discreetly in the background. He so successfully suppressed any hint of partisanship that in 1877 Mackenzie offered to renew his appointment when his term expired the following year. Some prominent Liberals in Halifax saw the reappointment as a crude and corrupt means of neutralizing a formidable political opponent. Archibald probably realized that his age and his politics made it unlikely that he would be appointed again to the bench. In any case he decided to remain in office until July 1883. Two years later he would be made a kcmg.

Archibald continued to participate in a variety of public activities. In October 1883 he took part in the inauguration of the Dalhousie law school. In his address he stressed the need for lawyers to understand the moral values that were the basis of civilized society. The following year he was approached by James Ross*, president of Dalhousie University, to spearhead an expansion and reorganization of the university, made possible, in part, by a donation from Sir William Young, and in November was appointed chairman of the board of governors. He was soon deeply involved in negotiations with the city of Halifax, which culminated in an agreement whereby the university received a new site for a campus in exchange for the existing one on the Grand Parade. Archibald also had a hand in arrangements for the affiliation of the Halifax Medical College with the university. Negotiations for a union with King’s College in Windsor, however, proved unsuccessful.

One of the founders of the Nova Scotia Historical Society in June 1878, Archibald served as its president from 1886 until his death and read papers on diverse subjects at its meetings. He was outraged by charges that documents relating to the expulsion of the Acadians from Nova Scotia in 1755 published in a volume edited by provincial record commissioner Thomas Beamish Akins in 1869 had been selected in a biased manner. Archibald presented two papers on the deportation in 1886 in which he contended that the British action was entirely justified and that any blame for mistreatment of the Acadians should fall on the French government and the Roman Catholic clergy. His account reflected a self-conscious patriotism as well as tinges of racism. While he was preparing his essays, he was also helping to establish a Halifax branch of the Imperial Federation League.

The essays were controversial because of both their content and Archibald’s prominence. He was soon exchanging letters with Catholic archbishop Cornelius O’Brien* in the Halifax newspapers. These letters came to the attention of historian James MacPherson Le Moine*, who arranged to have Archibald address the Royal Society of Canada. Archibald also sent a copy of his essays to historian Francis Parkman, who, in an anonymous review, cited Archibald’s work to support his own conclusions.

In July 1888 Archibald received a request to stand as the Conservative candidate in a federal by-election in Colchester County, made necessary by the appointment of Archibald Woodbury McLelan* as lieutenant governor. Both political parties were disorganized and the Conservatives, faced with a potentially divisive contest to select a candidate, turned to Archibald. Perhaps flattered that he could still be of service and supportive of Macdonald’s policies (including the hanging of Riel), he agreed and carried the seat easily. He did not make any speeches in the commons, however, and in 1891 he was too ill to consider standing for re-election. He died in Truro in December the following year. His funeral was attended by a wide array of public figures. Along the route of the procession blinds were drawn and businesses and schools were closed. After the sale of his real property, his estate totalled some $50,000, a modest sum for one of his position.

In his career Adams George Archibald embodied many of the leading ideas of his day, such as a strong belief in education as a means of betterment and the conviction that technology would promote progress, both material and moral. He accepted the concept that society rested on moral principles, which he implicitly identified with Great Britain. He was a firm believer in self-government as expressed in the cabinet system. He was undoubtedly the very model of a gentleman and scholar who had dedicated his life to public service.

Sir Adams George Archibald’s publications include “The expulsion of the Acadians,” pts.i and ii, N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 5 (1886–87): 11–38 and 39–95, and “First siege and capture of Louisbourg, 1745,” RSC Trans., 1st ser., 5 (1887), sect.ii: 41–53.

DUA, ms 1-1, A4. Mount Allison Univ. Arch. (Sackville, N.B.), Israel Longworth papers (mfm. at PANS). NA, MG 26, A, 518; RG 6, C2, 136, 353; RG 15, DII, 1, vols.228, 230. PAM, MG 12, A (mfm. at NA). PANS, MG 1, 244, no.236; 279, no.3; 771, no.7; 1798, F/15; 1840, F/4–5; MG 9, 2, 41; MG 100, 7, no.7; 104, nos.4–8C, 15, 18–20A; 138, no.5; 208, no.6A; 250, no.1; RG 3, 1, no.128; 2, no.302; RG 5, GP, 10, no.69; 11, no.34. Can., House of Commons, Journals, 1874, app.6. Manitoba: the birth of a province, ed. W. L. Morton (Altona, Man., 1965). N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 9 (1893–95): 197–201. Acadian Recorder, 1856, 1864–74. British Colonist (Halifax), 1864–75. Citizen (Halifax), 1864–73. Evening Express (Halifax), 1864–75. Evening Reporter, later Reporter and Daily and Tri-Weekly Times (Halifax), 1864–75. Halifax Herald, 29 Nov. 1892. Morning Chronicle (Halifax), 1864–75. Morning Herald (Halifax), 25 Dec. 1891. J. M. Beck, Joseph Howe (2v., Kingston, Ont., and Montreal, 1982–83); Politics of Nova Scotia (2v., Tantallon, N.S., 1985–89). A. D. Brannen, “Sir Adams George Archibald,” Colchester Hist. Soc., Proc., reports and program summaries, 1958–1967 (Truro, N.S., 1967), 21–28. R. S. Craggs, Sir Adams G. Archibald: Colchester’s father of confederation ([Truro, 1967]). Israel Longworth, Life of S. G. W. Archibald (Halifax, 1881). Morton, Manitoba (1967). The new peoples: being and becoming Métis in North America, ed. J. [L.] Peterson and J. S. H. Brown (Winnipeg, 1985). K. G. Pryke, Nova Scotia and confederation, 1864–74 (Toronto, 1979). N. E. A. Ronaghan, “The Archibald administration in Manitoba – 1870–1872” (phd thesis, Univ. of Man., Winnipeg, 1986). I. [M.] Spry, “The great transformation: the disappearance of the commons in western Canada,” Canadian plains studies 6: man and nature on the prairies, ed. Richard Allen (Regina, 1976), 21–45. Stanley, Birth of western Canada. Waite, Life and times of confederation. R. S. Bowles, “Adams George Archibald, first lieutenant-governor of Manitoba,” Man., Hist. and Scientific Soc., Trans. (Winnipeg), 3rd ser., no.25 (1968–69): 75–88. Chronicle-Herald (Halifax), 18 July 1959. Daily News (Truro), 29 June 1967. C. B. Fergusson, “Sir Adams G. Archibald,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 36 (1968): 4–58. Rosemarie Langhout, “Developing Nova Scotia: railways and public accounts, 1849–1867,” Acadiensis (Fredericton), 14 (1984–85), no.2: 3–28. Mail-Star (Halifax), 27 Oct. 1966. D. A. Muise, “Parties and constituencies: federal elections in Nova Scotia, 1867–1896,” CHA Hist. papers, 1971: 183–202. Elizabeth Parker, “Manitoba’s first lieutenant-governor,” Dalhousie Rev., 10 (1930–31): 519–24. D. N. Sprague, “The Manitoba land question, 1870–1882,” Journal of Canadian Studies, 15 (1980–81): 74–97.

Cite This Article

K. G. Pryke, “ARCHIBALD, Sir ADAMS GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/archibald_adams_george_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/archibald_adams_george_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | K. G. Pryke |

| Title of Article: | ARCHIBALD, Sir ADAMS GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |