Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

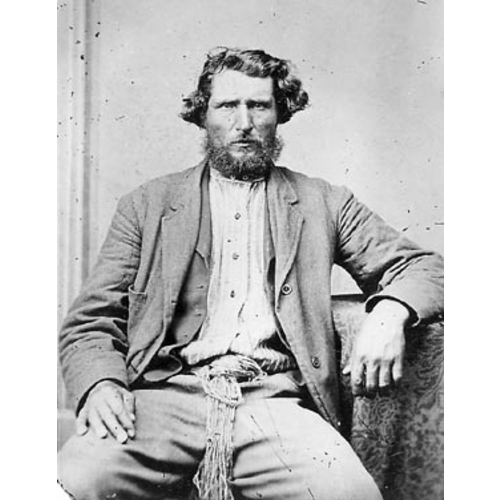

LÉPINE, AMBROISE-DYDIME, farmer, Métis leader, and politician; b. 18 March 1840 in St Boniface (Man.), fifth of the six children of Jean-Baptiste Lépine and Julie Henry; m. there 12 Jan. 1859 Cécile Marion, and they had 14 children, six of whom survived him; d. there 8 June 1923.

Ambroise Lépine’s father, an engagé of the Hudson’s Bay Company, was born in Saint-Jacques-de-l’Achigan (Saint-Jacques), Lower Canada, to Joseph Chevaudier, dit Lépine, and Marie-Anne Pellerin. His mother, the daughter of an English fur trader and an Indian woman, was a native of Ste Agathe (Man.). Lépine was educated at the Collège de Saint-Boniface. After his marriage to Cécile Marion, who was of French Canadian and Métis descent, the couple began farming in St Boniface on river lot 119. Lépine supplemented his income with freighting and hunting.

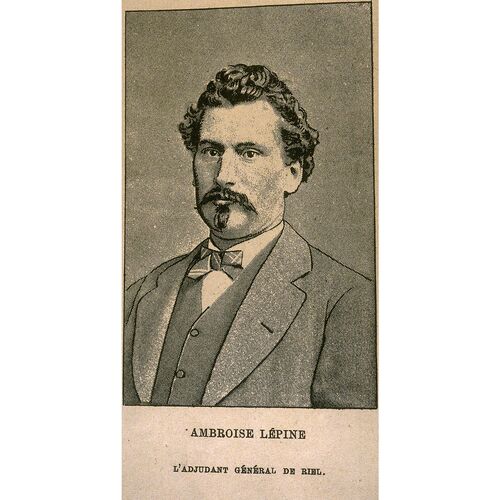

There is no evidence that Lépine was politically active prior to 1869, when the forthcoming transfer of Rupert’s Land from the HBC to Canada was announced. On his return to the Red River settlement (Man.) on 30 October from a freighting expedition to Fort Pitt (Sask.), he learned that the Métis, led by Louis Riel*, had taken steps to delay the transfer and force the Canadian government to negotiate the terms of union with the colony’s inhabitants. Apparently asked by Riel if he was “for or against the Métis,” Lépine replied that he was in favour of Métis rights. Riel immediately ordered him, with 14 others, to ride to Pembina (N.Dak.) to turn back the lieutenant governor designate, William McDougall*, at the border. On 7 December, on Riel’s orders, he led 100 Métis in the capture of Canadians who were garrisoned in the house of one of their leaders, John Christian Schultz*. On 8 Jan. 1870 Riel’s provisional government appointed Lépine adjutant general to administer justice in the settlement. A few weeks later Lépine was also elected to represent St Boniface in a convention of 40 representatives of the settlement and he was subsequently appointed head of the military council, a subcommittee of the convention.

A contemporary speculated that Riel chose Lépine as his military chief because of the respect he commanded among the Métis tripmen and buffalo hunters. The Reverend Roderick George MacBeth* described Lépine as a man of prodigious strength, “standing fully six feet three and built in splendid proportion.” Reputedly a skilled plainsman, he was assumed to have been the natural leader of the soldiers of the resistance. This assessment does not bear careful scrutiny, however. There is no evidence that Lépine was a buffalo hunter and in March 1870 diarist Alexander Begg* noted that there was open revolt amongst the Métis over Lépine’s conduct. Riel patched up the affair, but ordered him not to be so overbearing. A more convincing explanation for Lépine’s advancement in the Riel party involves his loyalty to Riel and their close personal and family ties. Furthermore, Lépine was allied with the Catholic Church and many of Riel’s most trusted advisers during 1869–70 were Catholic priests.

In mid February 1870 Lépine and a group of Métis arrested Major Charles Arkoll Boulton* and a number of men after their plan to capture Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg) aborted. Among the prisoners was Thomas Scott*, whose behaviour soon angered his Métis guards. Riel ordered Scott court martialled on 3 March. As the military leader, Lépine headed the tribunal that tried Scott and found him guilty of rebelling against the government and it was he who declared that Scott should be executed. It was Riel, however, who turned down all pleas to spare Scott’s life.

Scott’s execution would have profound repercussions for both Riel and Lépine. When they later became fearful about reaction to the execution, especially in Protestant Ontario, they were assured by Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché* that an amnesty would be granted covering all the events of the resistance. The arrival of the troops led by Colonel Garnet Joseph Wolseley* on 24 Aug. 1870, along with warnings that their lives were in danger, persuaded Riel and Lépine to flee. They eventually ended up at the Catholic mission of St Joseph (N.Dak.), but over the next year they would move back and forth across the boundary, causing a good deal of excitement in the Red River settlement.

In October 1871 Lépine was chosen captain of the troops from St Boniface who volunteered to defend the settlement against the Fenian invasion led by William Bernard O’Donoghue*. He hoped that these loyal actions would result in amnesty, but it was not forthcoming. Although the government had little interest in bringing him and Riel to trial, fearing the uproar that such a move would cause throughout the country, certain individuals wanted vengeance. Given the increasing danger of their arrest, he and Riel were persuaded by Taché to go into voluntary exile in the United States. Lépine was unhappy there. Alternately bored and afraid for his life, he also worried about the welfare of his family and by May 1873 had resolved to go home.

Back in Manitoba, Lépine returned to his farm. His arrest on 17 September on the charge of murdering Scott was the initiative of two Canadians who had been imprisoned by the Métis during the troubles and it caused a great stir in Manitoba. The trial was delayed several times since the judges were unwilling or unable to decide if the Court of Queen’s Bench had jurisdiction to try the case. The matter was settled in June 1874 by the newly appointed provincial chief justice, Edmund Burke Wood*, who released Lépine on $8,000 bail.

The trial, which began on 13 October, lasted until 4 November, when the jury, consisting of six French- and six English-speaking members, returned a verdict of guilty with the recommendation of mercy. Wood, comparing the execution of Scott to a “savage atrocity,” sentenced Lépine to death by hanging. The conviction and sentencing elicited great excitement and indignation in Red River and the rest of Canada. Le Nouveau Monde (Montréal) [see Alphonse Desjardins*] demanded that the federal French Canadian ministers secure a pardon or resign their seats, and the Legislative Assembly of Quebec passed a unanimous resolution asking for amnesty. The federal Liberal government of Alexander Mackenzie* turned the matter over to the governor general, Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*], hoping that the intervention of the imperial authorities would be useful in reconciling the Orange faction in Ontario to a policy of clemency. Dufferin eventually decided that Lépine’s sentence should be commuted to two years in prison along with the forfeiture of his civil rights. A few months later, in April 1875, both Riel and Lépine were offered an amnesty on the condition that they accept a five-year banishment from Canada. Unlike Riel, Lépine refused the offer, choosing to serve out the balance of his sentence.

After his release from prison on 26 Oct. 1876 Lépine maintained close contact with Riel and Taché and remained active in Manitoba’s French-speaking community. In 1871 he had participated in the formation of the Union Saint-Alexandre to protect Métis interests in the new province and in 1878 he was elected vice-president of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste. The following year, when Riel tried to enlist him in the project of uniting the Métis and Indians of the northwest into a confederacy, he travelled to Montana Territory to meet with Riel. Although he spent the winter with the Métis of the region, he took the advice of Taché, who was worried about possible trouble in the northwest, and left before seeing Riel. This decision, and his siding with Taché over the Métis leader, seems to have been a turning-point. From then on he stayed out of Métis politics.

The Lépine family remained in St Boniface until 1882 when they moved to Grande Pointe, nine miles southeast of Winnipeg. After a fire destroyed their farm there in 1891, they settled amongst relatives and friends at Oak Lake. Lépine’s prospects did not improve. Poor harvests left his family nearly penniless and English-speaking settlers soon overwhelmed the Métis community. By 1902 he was homesteading near Forget (Sask.), close to his sons. In 1908 his wife, Cécile, died and he moved in with his children.

In 1909 the Winnipeg Evening Telegram reported that Lépine, impecunious, was in Winnipeg and was willing to disclose the location of Thomas Scott’s body for money. Lépine at this time also maintained that Roman Catholic priests Jean-Marie-Joseph Lestanc and Noël-Joseph Ritchot* had advised Riel to execute Scott. The church was quick to reject these allegations and silence Lépine, who then denied that he had ever offered to reveal the location of Scott’s body. Sometime after 1909 he sold his land near Forget and bought a summer resort in Quibell, Ont., near Lake of the Woods. He lived there with a granddaughter. Shortly before his death Lépine had his civil rights restored and he moved back to St Boniface. He died at the Hôpital de Saint-Boniface in 1923. His funeral was attended by the former premier of the province, Sir Rodmond Palen Roblin*, and other dignitaries and he was buried in the St Boniface cemetery next to Riel.

Ambroise-Dydime Lépine played a major role in the events of 1869–70, but his contribution was of a different order than that of Riel. Not a natural politician or a strategist, Lépine was a loyal follower of Riel and the church. When the interests of Riel and the church began to diverge in 1879, he sided with Taché and the church. He had, he said, risked his life once for the Métis cause and was not willing to do so again. He did continue to work for the Métis in other ways, helping to establish the historical committee of the Union Nationale Métisse Saint-Joseph du Manitoba in 1909, which would spearhead the drive to publish Auguste-Henri de Trémaudan’s Histoire de la nation métisse dans l’Ouest canadien in 1935.

Arch. de la Soc. Hist. de Saint-Boniface, Winnipeg, Dossiers généalogiques; Fonds de la Corporation archiépiscopale catholique romaine, sér. Langevin; sér. Taché. NA, RG 15, 1322. PAM, HBCA, E.6/2; MG 3, B19; D1; D2; P 4895, Émile Lépine fonds, file 2. Manitoba Free Press, 9 March 1909. Le Métis (Saint-Boniface), 30 nov. 1872. Winnipeg Evening Telegram, 8, 11 Feb. 1909. Alexander Begg, Alexander Begg’s Red River journal and other papers relative to the Red River resistance of 1869–1870, ed. W. L. Morton (Toronto, 1956). Alexander Begg and W. R. Nursey, Ten years in Winnipeg: a narration of the principal events in the history of the city of Winnipeg from the year A.D. 1870 to the year A.D. 1879, inclusive (Winnipeg, 1879). J. M. Bumsted, “The trial of Ambroise Lépine,” Beaver (Winnipeg), 77 (1997–98), no.2: 9–19. Can., House of Commons, Select committee on the causes of the difficulties in the North-West Territory in 1869–70, Report (Ottawa, 1874). The Canadian north-west, its early development and legislative records . . . , ed. E. H. Oliver (2v., Ottawa, 1914–15). Dufferin–Carnarvon correspondence, 1874–1878, ed. C. W. de Kiewiet and F. H. Underhill (Toronto, 1955; repr. New York, 1969). J. A. Kerr, “‘I helped capture Ambroise Lépine’” Canadian Magazine, 79 (January–May 1933), no.5: 13, 40–41. Constance Kerr Sissons, John Kerr (Toronto, 1946). Denys Lamy, “Ambroise-Didyme Lépine,” Les Cloches de Saint-Boniface (Saint-Boniface), 22 (1923): 114–16. R. G. MacBeth, The making of the Canadian west: being the reminiscences of an eye-witness (Toronto, 1898). Preliminary investigation and trial of Ambroise D. Lepine for the murder of Thomas Scott . . . , comp. G. B. Elliott and E. F. T. Brokovski (Montreal, 1874). Louis Riel, The complete writings of Louis Riel, ed. G. F. G. Stanley (5v., Edmonton, 1985). G. F. G. Stanley, Louis Riel (Toronto, 1963).

Cite This Article

Gerhard J. Ens, “LÉPINE, AMBROISE-DYDIME,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lepine_ambroise_dydime_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lepine_ambroise_dydime_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gerhard J. Ens |

| Title of Article: | LÉPINE, AMBROISE-DYDIME |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |