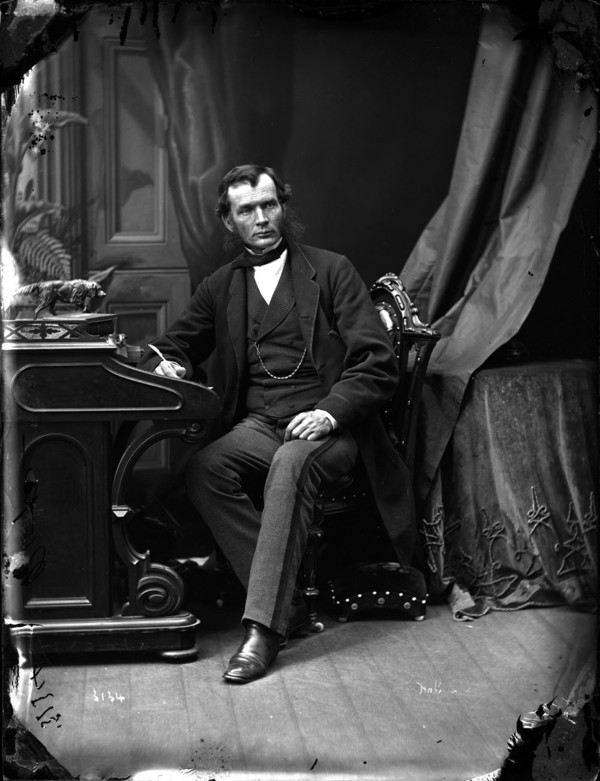

POPE, JOHN HENRY, farmer, lumberman, railway entrepreneur, and politician; b. 19 Dec. 1819 in Eaton Township, Lower Canada, son of John Pope and Sophia Laberee; m. 5 March 1845 Percis (Persis) Maria Bailey, and they had three children, two of whom survived infancy; d. 1 April 1889 in Ottawa, Ont.

John Henry Pope’s paternal grandparents had moved as loyalists from Massachusetts to the Eastern Townships and his father had eventually settled on a farm in what is now the town of Cookshire. Pope went to local schools, but his education was unsystematic; his writing, doubtless like his speech, always retained a highly original syntax and force. His main ambition as a young man was to have the best farm in the district, and by the time of his marriage in 1845 he had probably taken over the main work on his father’s farm. The family land was situated in a country of broad valleys and rolling uplands heavily forested in maple, birch, larch, pine, and cedar. Throughout his life, Pope continued to work on his farm and was noted for his improvement of cattle breeds through the importation of thoroughbred stock.

He took an active interest in local affairs, representing Eaton Township on the Sherbrooke County Council in the 1840s. During the rebellion of 1837–38 he had been a member of the Eaton Township militia and had done guard duty at the court-house in Sherbrooke. He continued his military interests by joining a cavalry company in the Eaton militia and under the Militia Act of 1855 was named captain of the Cookshire Troop of Volunteer Militia Cavalry. As an officer, he preferred good local men who knew the countryside and its ways rather than imported Britishers. At the time of the Trent crisis in 1861 [see Sir Charles Hastings Doyle], Pope told Alexander Tilloch Galt* that he did not want to run the risk “of being thrown into the hands of some half-witted retired officer of the Army, or some pampered Frenchman, or some old fogy like Colonel – of this district.”

Like his forebears, Pope was generally anti-American. In 1849 he took a firm stand against the strong annexationist movement in the Eastern Townships, a choice which put him in opposition to such regional notables as Galt, John Sewell Sanborn*, Hollis Smith*, and John Joseph Caldwell Abbott*. In July 1849 Pope attended the meeting in Kingston, Canada West, of the British American League, many of whose members favoured annexation to the United States. His purpose in attending was to attempt to keep the debate within constitutional limits, and there he first met John A. Macdonald*, who was to become his friend and political chief in the Liberal-Conservative party. In the general election of 1851 Pope unsuccessfully opposed Sanborn, who had been elected for Sherbrooke County in 1850 as an avowed annexationist; Pope again ran without success against Galt in an 1853 by-election in Sherbrooke Town and against Sanborn in the new riding of Compton County in the general election of 1854. Sanborn was not a candidate in Compton in 1857–58 general election, and Pope was elected by acclamation. He continued to represent the county without interruption in the assembly of the Province of Canada until confederation and in the House of Commons until his death in 1889. He frequently ran unopposed and, when he did face challengers, received at least two-thirds of the votes cast. In June 1864 he and Alexander Morris acted as intermediaries between George Brown* and John A. Macdonald in the initial discussions that led to the formation of the “Great Coalition.”

Pope combined his duties as a politician with work on his farm and a wide variety of important business interests. With a partner, Cyrus S. Clarke of Portland, Maine, Pope owned the Brompton Mills Lumber Company which operated large sawmills at Brompton Falls (Bromptonville) in the eastern part of Compton County. One of his first acts as a legislator was to sponsor a bill to amend the charter issued in 1855 for the Eastern Townships Bank, so that it could begin operations. The Montreal banking community was unsympathetic to this Eastern Townships venture, but Pope and other promoters of the bank managed to subscribe almost half the capital locally and he remained a director of the successful bank until his death. Pope was an incorporator in 1866 with Andrew Paton of the Paton Manufacturing Company, a woollen mill in Sherbrooke. In 1868 George Stephen* joined them, thus beginning Pope’s long acquaintance with Stephen and the leading capitalists of the Bank of Montreal. By 1872 the Sherbrooke mill employed 500 workers. Pope was a director, as well, of the Sherbrooke Water Power Company, the Sherbrooke Gas and Water Company, and the Compton Colonization Society, and the honorary president and a large stockholder in the Eastern Townships Agricultural Association.

Late in the 1850s Pope had become involved in exploiting copper mines in Ascot Township, Compton County, and in the 1860s acquired lands in Ditton Township, also in Compton, which yielded gold until they were virtually worked out in the early 1890s. In the 1870s it was charged that Pope had obtained 4,200 acres in Ditton Township by misrepresentation or even fraud. A provincial government investigation in 1877, however, cleared Pope by maintaining that he had bought the lands from a man who had acquired them without the usual settlement duties and the customary crown reservation of gold rights. There is evidence that the form of patent was varied to suit the circumstances, and that Pope had probably acquired the lands legally, but only just. In addition, the investigator named by the province was Richard William Heneken, a fellow director of Pope’s in several Eastern Townships businesses. That Pope knew he had done well is probable. He always was to wear a massive gold chain and used to say, “I worked a good many years to get this chain – and got it at wholesale figures, too.”

Perhaps the most significant of Pope’s varied business dealings was the construction of railways. By the end of the 1860s short lines were frequently chartered in order to bring products to markets, but Pope had in mind a larger railway that would connect Sherbrooke, through Compton County, with Maine, and then continue to Saint John, N.B. The railway, of course, would serve his own constituency and his own lumber interests. The St Francis and Megantic International Railway was thus chartered federally in 1870 and the following year was given land and a construction subsidy by the government of Quebec. But competition from rival lines and difficulty in attracting capital impeded the railway’s construction. Pope felt it essential that local governments participate and succeeded in having the Compton County Council subscribe over $225,000 to the project. The appropriation was annulled when it was put to the rate-payers, but a new by-law was passed by council and ratified by the rate-payers favouring the county’s participation. This decision in turn was challenged in the courts and no railway bonds could be issued. Pope then put his own money into the company and 22 miles of track were laid by 1875. The project almost ruined Pope in health and purse, however, and in the same year the railway’s land grant reverted to the province. In 1883 the railway received a federal subsidy and in 1887 became part of the Canadian Pacific Railway. George Stephen, Pope’s business associate and the president of the CPR from 1881 to 1888, later said that the only reason the CPR took over the “Short Line” between Sherbrooke and Saint John was to relieve Pope of his personal commitments in the railway.

At the same time that he was heavily involved in business in the 1870s and 1880s, Pope was a leading cabinet minister in Sir John A. Macdonald’s governments. He was first appointed minister of agriculture in October 1871 and retained the office until the government’s resignation over the Pacific Scandal in November 1873. His view of Canada was not unlike Sir Charles Tupper*’s, that the country was a horizontal national market. Pope spoke frequently in parliament on the necessity of keeping a proper balance between expanding population and available markets and was opposed to accepting immigrants more quickly than they could be absorbed. In 1876 he endorsed Macdonald’s and Tupper’s views of what would become the National Policy: if the Americans were determined to keep Canadian products out of American markets, then Canada should restrict American access to Canadian markets.

Macdonald was to find Pope a valuable ally. Pope was impressive, tall, incisive, and commanding; but if he was at times terse, he was rarely hasty, and he was in general tolerant of opponents. Like the “practical lumberman” he once described himself as being, he gave a strong impression of powers held in reserve. A sure-footed and shrewd man of action, he had a tremendous capacity for work and little for leisure. His speeches in parliament called for fair play and no special favours. He disliked clerical interference in elections, even if eliminating it meant compromising a Conservative victory. In January 1875 he supported Alexander Mackenzie*’s proposal of amnesty for Louis Riel and Ambroise-Dydime Lépine*, although he argued that even their five-year banishment was stupid. He wanted them granted “a full and complete pardon” because there was “no reason why they should be persecuted if the country would gain nothing thereby.”

On Macdonald’s return to power in 1878, Pope again became minister of agriculture, a portfolio that now included responsibility for the Library of Parliament, the infant public archives, and the census. His departmental work was done well, even if he frequently took on additional responsibilities as acting minister of railways and canals during the absence of Tupper. Pope became identified as one of the strongest supporters in the government of a railway to the Pacific. In 1879, when there was no one yet ready to undertake the project, he even thought of organizing a company to do it himself. After the fruitless attempts in 1879–80 of Macdonald, Tupper, and himself to find capitalists in London to build the railway, Pope suggested that George Stephen, Donald Smith*, and their partners in the St Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railway be invited to build it. In 1878–79 the group had scored a financial coup in acquiring this railway, and Pope urged that their evident interest be encouraged before they invested their profits elsewhere. The move was successful, and on 21 Oct. 1880 the CPR construction contract was signed. As a friend and associate of Stephen, Pope was a strong advocate of the CPR throughout the five-year period of its construction and its financial difficulties. He did not hesitate, however, to criticize Stephen and his partners in 1882 for the steep freight rates they charged western farmers to transport grain over their Minnesota-Manitoba line. Yet it was largely owing to Pope that the CPR survived the major financial crisis of January 1884 when he persuaded a desperately reluctant Macdonald to brave the opposition of the Liberals, some cabinet ministers, and a large part of the Conservative caucus to aid the CPR with a $30 million loan. Stephen was grateful and on 4 Sept. 1884 wrote Macdonald in concern about Pope’s health: “He is criminally careless of himself & unless you take him in hand . . . he will break down. His life & services to Canada at this moment can hardly be overestimated, second only to your own.”

In September 1885, two months before the completion of the CPR, Pope was appointed minister of railways and canals. He took up the portfolio with his usual tenacity, but when Stephen resigned as CPR president in 1888 Pope was forced to deal with William Cornelius Van Horne*, an American. The two men were both fiercely determined and they quarrelled bitterly during the long arbitration over the British Columbia section of the transcontinental which had been built in the early 1880s by the government and which the CPR was to take over. Pope was also ill by this time. His family had been trying since 1887 to persuade him to retire, but he found that there was too much work to be done. In August 1888, holding the fort as he did so often while Macdonald was with his family at Rivière-du-Loup, Pope crawled to Montreal more dead than alive. There George Stephen saw him, looking “shrunk and worn beyond description.” Pope none the less stuck to his office until two weeks before his death from cancer of the liver on 1 April 1889.

Pope left a substantial estate of $130,000 in cash, as well as lands, farm stock and buildings, and his home. The legatees were his wife, his son Rufus Henry*, who succeeded his father as mp for Compton, and his daughter Elizabeth, the wife of William Bullock Ives*, Conservative mp for Richmond and Wolfe since 1878. Elizabeth received the money “for her own use and absolutely free from the control of her husband.” His three grandsons and the Church of England in Cookshire also received bequests.

John Henry Pope was a man of unusual capacity. His unprepossessing face concealed a mind of great penetration and judgement. His manner in the House of Commons, although not elegant, was very effective. Like Macdonald, he was no reformer, and he regarded men and situations as realities which must be bent to one’s purpose. His arguments were telling, and few men had such enormous influence on Macdonald. During the CPR crisis in 1884, for instance, Pope was ruthless and unsentimental. “You will have to loan them the money,” he told Macdonald, “because the day the CPR busts, the Conservative party busts the day after.” It was perhaps the only argument that would have influenced Macdonald.

[Professor Andrée Désilets, Université de Sherbrooke, has made several useful suggestions in the preparation of this biography, and the bibliography she and her colleagues have compiled, Bibliographie d’histoire des Cantons de l’Est ([Sherbrooke, Qué.], 1975), is an essential beginning for any work on the history of the region.

There is no major collection of Pope papers. All the family papers seem to have disappeared, and this loss accounts in part for the dearth of information about Pope. The largest single source is Pope’s correspondence with Sir John A. Macdonald in the Macdonald papers at PAC (MG 26, A). There is a limited but interesting collection of Pope letters in the Morris family papers at the McCord Museum, Montreal, mostly concerning the St Francis and Megantic International Railway, 1871–73. There are Pope letters in the Sir A. T. Galt papers at PAC (MG 27, I, D8) and in the Fonds Langevin at ANQ-Q (AP-G-134). Newspapers of the Eastern Townships report Pope’s speeches: Stanstead Journal (Rock Island), Sherbrooke Gazette and Eastern Townships Advertiser, Sherbrooke News, and Le Pionnier de Sherbrooke. Le Franc-Parleur (Montréal), 2 févr. 1877, raises some questions about Pope’s land transactions.

There is a considerable correspondence in the records of the Quebec Crown Lands Department (ANQ-Q, PQ, TF) on Pope’s acquisition of land in Ditton Township alleged to be valuable for gold. The land records of Compton County, at the registry office in the county town of Cookshire (BE, Compton (Cookshire)), contain a wealth of references to Pope’s purchases and sales of land and Pope’s will.

There is an extended sketch of Pope by his friend Charles Herbert Mackintosh*, editor of the Ottawa Daily Citizen and later lieutenant governor of the North-West Territories, in L. S. Channell, History of Compton County and sketches of the Eastern Townships, district of St. Francis, and Sherbrooke County . . . (Cookshire, Que., 1896; repr. Belleville, Ont., 1975), 155–65, a work valuable as well for the farming and railway background of Pope and of his constituency. Mackintosh also gives an appreciation of Pope in an obituary in the Ottawa Daily Citizen, 2 April 1889. For Pope’s marriage certificate, consult: AC, Saint-François (Sherbrooke), État civil, Épiscopaliens, Episcopal Church (Eaton), 5 March 1845. On Eaton Township, see: C. S. Lebourveau, A history of Eaton; being an historical account of the first settlement of the township of Eaton . . . (n.p., 1894; repr. Sherbrooke, 1965); for references to the Eastern Townships in general, The Eastern Townships gazetteer and general business directory . . . (St Johns [Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu], Que., 1867; repr. Sherbrooke, 1967), is useful.

It is fair to say that Pope has been neglected in more recent times, though there are numerous references to him in Cornell, Alignment of political groups; Creighton, Macdonald, old chieftain; J. Hamelin et Roby, Hist. économique; M. Hamelin, Premières années du parlementarisme québécois; W. K. Lamb, History of the Canadian Pacific Railway (New York and London, 1977); Terrill, Chronology of Montreal; and Waite, Canada, 1874–96. The only modern work on Pope is W. S. Laberee, “Hon. John Henry Pope, Eastern Townships politician” (ma thesis, Bishop’s Univ., Lennoxville, Que., 1966). p.b.w.]

Cite This Article

P. B. Waite, “POPE, JOHN HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pope_john_henry_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pope_john_henry_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | P. B. Waite |

| Title of Article: | POPE, JOHN HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 24, 2025 |