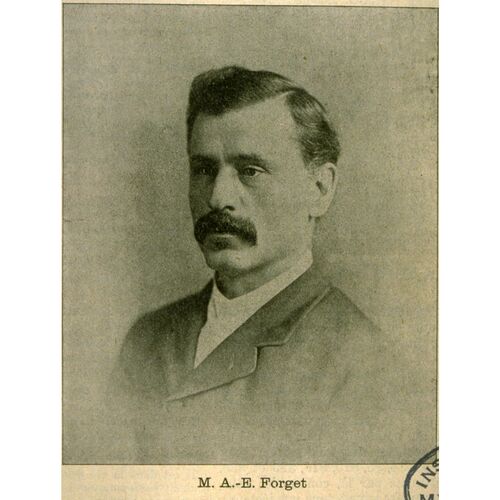

FORGET, AMÉDÉE-EMMANUEL (baptized Emmanuel-Amédée-Marie), lawyer, office holder, civil servant, and politician; b. 12 Nov. 1847 in Marieville, Lower Canada, son of Jacques-Jérémie Forget and Marie-Flavie Guenette; m. 17 Oct. 1876 Henriette A. Drolet in Montreal; they had no children; d. 8 June 1923 in Ottawa.

Born to a devoutly Roman Catholic family, Amédée-Emmanuel Forget attended the village school in Marieville, the School of Military Instruction of Quebec, and the Collège de Marieville. His father, a teacher, sent him on occasion to spend time with a family in St Albans, Vt, to master English. Forget considered entering the priesthood but turned it down for law, which he pursued in the Montreal office of Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau*. Called to the bar in 1871, he continued to work with Chapleau, whom he accompanied to Winnipeg in 1874 for the legal defence of Ambroise-Dydime Lépine and his Métis companions. He became intrigued by the west and the possibility of a career there occurred to him. Tall and slim, he projected a dignified bearing. Those who knew Forget described him as charming and considerate, and he was noted for his wit, ingenuity of mind, and diplomatic skills. Legal colleagues were convinced that he was destined for a brilliant career in the courtroom; many were surprised when he looked to public service.

The triumph of the Liberals in the federal election of 1874 made patronage appointments for party stalwarts possible. Forget, an ardent Liberal, was not slow in forwarding his claim. He pressed his contacts in government for a position, reminding them of his fluent bilingualism and work during the election. The canvassing succeeded: on 21 May 1875 he was made a secretary of the commission to enumerate mixed-blood settlers entitled to land grants under the Manitoba Act. Forget arrived in the western province in June and was responsible, with Commissioner Matthew Ryan, for the French-speaking parishes. Following his return to Quebec after the work ended in January 1876, Forget practised law for a while in Saint-Hyacinthe in partnership with Honoré Mercier*, but it was simply an interlude before taking up another appointment he had been soliciting. Ottawa had moved to establish a new governing council for the North-West Territories and on 7 Oct. 1876 David Laird*, then minister of the interior, was made lieutenant governor and Indian superintendent. Forget became his secretary and clerk of council, a posting that required his immediate move west with his new wife and a winter at Fort Livingstone (Livingstone, Sask.), where on 8 March 1877 council held its first session. Forget’s role involved preparing the initial ordinances and assisting in the government’s move to Battleford (Sask.) that summer.

The Forgets bought a farm and entered into Battleford’s lively social life. In addition to the work of council, Forget assisted Laird in his dealings with the native population, which included travelling to make the annual treaty payments. Laird found such tasks tiresome and he resigned as Indian superintendent in February 1879, though he continued as lieutenant governor. That spring the buffalo disappeared and starving Indians began turning up at Battleford. Their presence alarmed the settlers; Henriette Forget, for one, was afraid to leave her house. Difficult negotiations followed and, when provided with food, the visitors returned to their reserves. These experiences with native affairs would serve Forget well in subsequent years. During a summer visit to Edmonton with Laird, the Forgets met Edgar Dewdney*, who had arrived to take up the new position of Indian commissioner; in late 1881 he became lieutenant governor as well. Although these appointments came from a Conservative government, that of Sir John A. Macdonald*, Forget remained clerk of council.

The decision to build the Canadian Pacific Railway along a southern route across the prairies led to the creation of a new capital, Regina. The Forgets moved there in February 1883. As the number of elected councillors and the volume of legislation grew, Forget’s duties expanded; “a capital officer” in Dewdney’s estimate, he met the challenge easily. One of council’s initiatives was the creation of a system of education. Legislation in 1884 allowed for a board of education divided into Catholic and Protestant sections, each controlling its own teachers, schools, and curriculum [see Charles-Borromée Rouleau*]. Forget, who sat as a Catholic representative from 1886, emerged as a principal defender of the sectarian and bilingual nature of the system, features that came under increasing attack from the Anglo-Protestant element of the population. In 1892 the board was replaced by the Council of Public Instruction, which brought education under a single authority. Forget vehemently opposed this measure and joined the Catholic hierarchy in a futile attempt to have it repealed. Named to the council of instruction without his approval, he nonetheless stayed to fight for Catholic rights, though he was never as intransigent as some clergy. He could find no objection, for instance, to the textbooks prescribed by the council but denounced by Father Hippolyte Leduc and others.

In the summer of 1884 Dewdney had become concerned about reported restlessness among the Métis of the District of Saskatchewan. Their most important grievance was lack of security of land tenure. The arrival of Louis Riel* in July seemed to escalate the agitation and Dewdney decided to investigate. Known to the Métis for his work in Manitoba, Forget was among those dispatched. During his week in September in the area of Batoche and St Laurent (St-Laurent-Grandin), he interviewed Riel and Gabriel Dumont*, among other members of the community, and suggested that Riel be appointed to the territorial council. This proposal, which Riel rejected, had not been endorsed, yet it reflected official thinking on how to neutralize the Métis leader. In his report to Dewdney, Forget noted that the Métis were determined and were expanding their list of demands; appended was a petition outlining Riel’s specific requirements on the land question. Forget’s major concern was the decline of missionary influence since Riel’s arrival. He proposed immediate help with education and agriculture and action on the land issue. The government procrastinated – the commission to settle Métis land claims was not established until March 1885. Forget was one of the three commissioners authorized to confirm existing holdings and offer scrip in compensation for aboriginal title. The North-West uprising was already under way when they began their determinations in April; the struggle and the scattered nature of settlement presented enormous challenges, and work continued into the following year. Meanwhile, the uprising was crushed and Riel was sentenced to hang. Many French Canadians had a certain sympathy for the Métis cause. Forget, who shared the sentiment, visited Riel in his Regina cell a number of times that fall and made no secret of his opposition to execution. When Riel mounted the scaffold on 16 November, he asked Father Alexis André* to convey his gratitude to Forget and his wife for their kindness. Dewdney noted Forget’s subsequent bitterness and felt that he could not be trusted completely.

When Dewdney left office in 1888 to enter the federal cabinet, the position of lieutenant governor and that of Indian commissioner were no longer to be held by the same individual. The former went to Joseph Royal*, a French Canadian mp, while the latter went to assistant commissioner Hayter Reed*. There was some opposition to having French Canadians as lieutenant governor and clerk of council at the same time, so Forget was removed and made assistant Indian commissioner, effective 3 Aug. 1888. After Reed left for Ottawa in 1893 to become deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs, Forget was put in charge of the Indian office at Regina. In October 1895 he became Indian commissioner for Manitoba, Keewatin, and the NWT.

Forget never deviated from the Department of Indian Affairs’ methods of strict surveillance and coercive tutelage with a view to assimilation. His language betrayed the prevailing prejudices against natives, whom he described as “a people who one generation past were practically unrestrained savages.” On reserves he sought out such signs of progress as “the desire to accumulate property” and a decline in paganism and the influence of medicine men. In his report for 1896 he was most optimistic about the potential of industrial schools for “uplifting a savage race and eradicating the nomadic and other inherent tendencies which centuries of a wild and barbarous life have firmly implanted.” The skills acquired in these schools were supposed to lead to self-sufficiency, especially through farming. Forget believed that Indians could be good farmers, but his department’s agricultural policy lacked coherence. Reed had insisted that Indians tend their crops with hand implements rather than modern machinery – they had to become frugal peasants before evolving into prosperous farmers – and on moving to Ottawa he ordered Forget to persist. Forget was dubious about a policy that was opposed by agents and Indians alike, but he dutifully tried to enforce it. When besieged by requests to permit the use of machinery, he sometimes conceded on the understanding that harvesting by hand had been tried and that the crops were in danger of being lost. He was all too aware from agents’ reports that the policy only discouraged Indians from becoming agriculturalists.

Government officials and missionaries were virtually unanimous in recognizing that the continuation of native ceremonies such as the Sun and Thirst dances obstructed cultural and religious transformation. An amendment to the Indian Act in 1895 forbidding the torture and gift-giving segments of these ceremonies gave the authorities some power to combat the practices. Forget urged his agents to invoke the law if “prohibited and revolting” aspects were ever featured and to use the section of the act prohibiting trespass on reserves to keep visitors away and thereby limit the size of gatherings. He ensured that beef tongues issued to the Blackfoot were split to render them useless for the Sun Dance and he approved the withholding of rations from those who danced. Yet he was sufficiently pragmatic to realize that ceremonies could sometimes be condoned under strict conditions. Agreements struck with the Blackfoot were followed by appeals to the “better element” on the reserves to use their influence against future dances. The department approved Forget’s use of “wise discretion.”

The victory of Wilfrid Laurier* and the Liberals in 1896 brought great satisfaction to Forget, who was a friend of the new prime minister. It also opened the door to higher office, especially important to a Liberal who had laboured long in a bureaucracy dominated by Conservatives, and paved the way for Forget’s most enduring contribution to Indian administration: a radical restructuring of western operations. Clifford Sifton, the new interior minister and superintendent general of Indian affairs, was determined to slash the department’s operating budget, especially on the prairies, where treaty obligations and security concerns kept costs high. Happy to oblige, Forget provided the blueprint. The Indian commissioner’s office was moved to Winnipeg in 1897 and made smaller; its role was reduced to inspecting agencies and schools. The Manitoba superintendency was abolished and agencies were eliminated. Within two years 57 employees had resigned or been dismissed, and the salaries of agents, clerks, and farm instructors had been cut. These measures did produce savings, but it became clear that purging Conservatives was also part of the restructuring. As vacancies opened up, they were filled with Liberals. A willing distributor of the spoils, Forget accepted nominations from prominent western Liberals such as Frank Oliver* and James Hamilton Ross*, and he issued a circular instructing agents to contract for supplies only with government supporters. He was irked when a copy was leaked to the press by a disgruntled employee, who he suspected was on the termination list.

Forget had been suffering for some years from a chronic infection of the spinal cord, a condition that baffled his doctors and impaired his work. With the Liberals in power, however, a less demanding appointment was conceivable. Royal’s successor as lieutenant governor, Charles Herbert Mackintosh*, was to retire in 1898. Forget made his interest in the position known to Laurier and Sifton but he was disappointed when it went to Malcolm Colin Cameron*, an Ontario Liberal. His hopes revived when Cameron died in September 1898. This time he was successful and the appointment was made effective 13 October. The news was generally welcomed in the western press, but there was dissent. Conservative papers were critical of Forget’s partisanship in the Indian office and some Catholics felt that his support for the Laurier-Greenway compromise of 1897 on the Manitoba school question had been a “base betrayal.”

Most of Forget’s work as lieutenant governor was routine and ceremonial. With responsible government entrenched by an amendment to the North-West Territories Act in 1897, political initiative had passed from the office. Along with his easy duties came substantial benefits, including residence in Government House in Regina. One of the finest houses in the west, it became the scene of lavish entertainments. Forget enjoyed his new role immensely. Although ill health occasionally kept him from his functions, he made a point of visiting many of the communities in his domain. His appearances at schools, country fairs, and other events were occasions for grand speeches laced with the boosterism and imperialist jingoism that audiences loved. The man who flaunted his credentials as a true Northwester was never slow to praise the prospects of the region, even to the point of stretching his listeners’ credulity. On a visit to Montreal in 1904, for example, he claimed there were no poor people in the NWT.

Forget’s friendship with Laurier was of no small importance after 1898. He was a trusted confidant and Laurier sought his advice on party interests and such delicate territorial matters as language, religion, and schools. As his term drew to a close, there was talk of a senatorship, but he preferred reappointment. He explained to Laurier that he had not managed his finances well and would be better able to plan for retirement were a second term offered. The prime minister obliged and Forget was sworn in on 4 April 1904 in Montreal, where he had gone for medical treatment.

In the general election in November, Laurier was returned with a majority. The NWT were now represented by 10 mps, 7 of them Liberals, a balance that strengthened the prime minister’s hand in determining the region’s political future. The Autonomy Acts of 1905 granted provincial status to Alberta and Saskatchewan. Forget learned in July 1905 that Laurier had chosen him as lieutenant governor of the latter, an appointment he had not solicited but gratefully accepted. His inauguration in Regina on 4 September was attended by Laurier and Chief Justice Arthur Lewis Watkins Sifton. The position allowed Forget to influence the composition of the province’s first government. Former territorial premier Frederick William Gordon Haultain* was the logical candidate for the provincial post, but he was a Conservative and opposed the Autonomy Acts’ allowance for separate schools and federal control of land and natural resources. Forget feared he would stir up trouble over these issues. With Liberals in most of Saskatchewan’s federal seats, he felt justified in calling on provincial Liberal leader Thomas Walter Scott* to become premier. The choice, predictably enough, was not well received in the Tory press; the Toronto Mail and Empire denounced Forget as Laurier’s “instrument” and cartoons showed Haultain facing a firing squad that included Forget. In the election that December, his decision was vindicated by the defeat of Haultain’s Provincial Rights party.

On 29 March 1906 Forget opened the first session of the legislature. Reading speeches from the throne, signing bills, and carrying out other rituals of office were all too familiar to him, and he fulfilled these duties with his customary dignity until the conclusion of his term on 13 Oct. 1910. During these years his health had continued to be a problem and he began to spend summers in Banff, Alta, to avail himself of the sulphur springs. Upon retirement, he and his wife made it their permanent residence. Early in 1911, however, Laurier informed him that a vacant Senate seat for Alberta was his. Forget moved to Ottawa and took his place in the Red Chamber in May 1911, but he made little impact. His only speech of note – a defence of the Laurier-Greenway compromise – was given in 1912, after which illness ate away his strength. He died in 1923 at his home on MacLaren Street and was buried at Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery in Montreal. His wife entered a convent, where she remained until her death in 1928.

Forget was an official of moderate importance who secured a number of noteworthy public positions in Manitoba, the NWT, and Saskatchewan during the pioneer period. His success was due to a combination of competence, charm, and fortuitous configurations in federal politics. He was liked by those he worked with, though his reputation was tarnished by his role of 1896–98 in the spoils system within the Department of Indian Affairs.

ANQ-M, CE601-S35, 17 oct. 1876; CE602-S21, 12 nov. 1847. LAC, MG 26, A: 42921-33, 42938-40, 90090-92, 90697-703; G: 20121-22, 29946-51, 41516-17, 78710-14, 99633-35, 176042-43, 185782-84; H: 18531; MG 27, II, D15: 12029, 12061-62, 12110, 28483, 128683; MG 29, D27; E106, 18: 463; RG 10, 3802, file 50320; 3825, file 60511-1; 3878, file 91837-23; 3964, file 148285. Saskatchewan Arch. Board (Regina), R-2.77 (A.-E. Forget scrapbook) (mfm.); R-39 (A.-E. Forget papers); SHS 21 (Saskatchewan Hist. Soc. files, corr. and biog. sketch on A.-E. Forget). Le Devoir, 11 oct. 1923. Morning Leader (Regina), 16 June 1923. Amy Nelson-Mile, “The Forgets had much to offer,” Regina Sun, 21 March 1999. N. F. Black, History of Saskatchewan and the North-West Territories (2v., Regina, 1913), 1. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, reports of the Dept. of Indian Affairs, 1895–96; Senate, Debates, 1911/12: 602–3, 758–59; 1923: 797–98. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Sarah Carter, Lost harvests: prairie Indian reserve farmers and government policy (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1990). J. W. Chalmers, Laird of the west (Calgary, 1981). T. [E.] Flanagan, Métis lands in Manitoba (Calgary, 1991). D. J. Hall, “Clifford Sifton and Canadian Indian administration, 1896–1905,” in As long as the sun shines and water flows: a reader in Canadian native studies, ed. I. A. L. Getty and A. S. Lussier (Vancouver, 1983), 120–44. John Hawkes, The story of Saskatchewan and its people (3v., Regina, 1924), 1. J. K. Howard, Strange empire: Louis Riel and the Métis people (New York, 1952; repr. 1974). M. R. Lupul, The Roman Catholic Church and the North-West school question: a study in church-state relations in western Canada, 1875–1905 (Toronto, 1974). Pioneers and prominent people of Saskatchewan (Winnipeg and Toronto, 1924). G. F. G. Stanley, The birth of western Canada: a history of the Riel rebellions (Toronto, 1936; repr., intro. T. [E.] Flanagan, 1992). [E.] B. Titley, The frontier world of Edgar Dewdney (Vancouver, 1999); A narrow vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver, 1986).

Cite This Article

E. Brian Titley, “FORGET, AMÉDÉE-EMMANUEL (baptized Emmanuel-Amédée-Marie),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/forget_amedee_emmanuel_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/forget_amedee_emmanuel_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | E. Brian Titley |

| Title of Article: | FORGET, AMÉDÉE-EMMANUEL (baptized Emmanuel-Amédée-Marie) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |

![Le nouveau lieutenant-gouverneur des T.N.-O. M. A.-E. Forget [image fixe] : Original title: Le nouveau lieutenant-gouverneur des T.N.-O. M. A.-E. Forget [image fixe] :](/bioimages/w600.7299.jpg)