Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

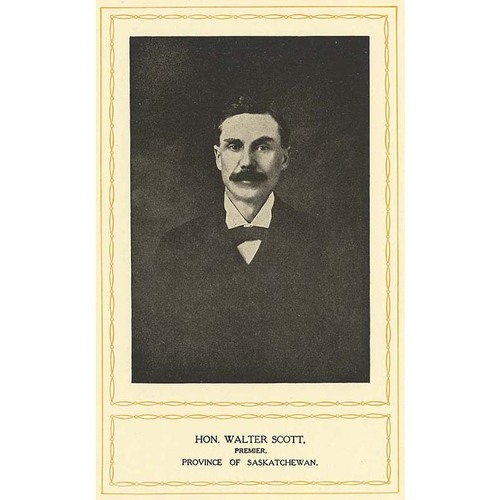

SCOTT, THOMAS WALTER, newspaperman and politician; b. 27 Oct. 1867 near Ilderton, Ont., son of George Scott and Isabella Telfer; m. 14 May 1890 Jessie Florence Read (d. 22 April 1932) in Regina, and they adopted her niece; d. 23 March 1938 in Guelph, Ont.

Walter Scott, Saskatchewan’s first premier, was a visionary with big ideas in a big land, but he came from humble roots. Born out of wedlock, a fact he hid from the public and even his friends for his entire life, he was raised by his mother and grandmother, Mary Telfer, on a small acreage outside Ilderton. In 1871 his mother married a local farmer, and Walter became part of their family. As a youth, he went west in 1885 to work on his uncle’s farm near Portage la Prairie, Man. His uncle, however, was at Batoche (Sask.) helping to suppress the Riel resistance [see Louis Riel*], so he took a job in Portage la Prairie with Christopher J. Atkinson of the Weekly Manitoba Liberal. Scott did manual chores but soon taught himself the art of journalism. He moved with his boss to Regina in 1886 and ultimately became half owner of the Regina Standard. In 1894 he purchased the Moose Jaw Times and the following year the Regina Leader from Nicholas Flood Davin*. Through his newspaper work he rubbed shoulders with local politicians and developed an interest in public affairs, including the controversial issues of the North-West school question [see Adélard Langevin*].

In 1900 Scott, a Liberal, ran against Davin in Assiniboia West for a seat in the federal House of Commons, and he won. He fast gained attention. In the commons, his attacks on the Canadian Pacific Railway and on Edmund Boyd Osler*, a Toronto mp and capitalist, over his railway dealings in the west, were notable for their unbridled partisanship. Returned in 1904, the outspoken Scott was in the thick of the debates in 1904–5 about the creation of new provinces out of the North-West Territories. Frederick William Gordon Haultain*, the territories’ premier, advocated a single province that would stretch from Manitoba to British Columbia. Liberal prime minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier*, on the other hand, wanted two provinces on the grounds that one would be too large. Public lands and natural resources, normally areas of provincial jurisdiction, constituted another area of disagreement. Laurier favoured continued control of these assets by the federal government so that Ottawa could manage the flood of immigrants who were settling in the west under the programs promoted by interior minister Clifford Sifton*. A third issue was the rights of minority religious groups, including Roman Catholics, to have their own separate schools.

There was some backing in the west for one province with its own land and resource rights and no separate schools, but Scott sided with Laurier and supported the formation of Alberta and Saskatchewan, with federal rights and legislated protection for separate schools. Haultain, in contrast, spoke out against Laurier’s plan. Even though he had been largely non-partisan as territorial leader, he campaigned for the Conservatives during two by-elections in June 1905 in Ontario, amid heated Protestant reaction to the intended provision for separate schools in the Autonomy Bills setting up the new provinces. Laurier concluded that Haultain was not a suitable candidate for premier of either of them.

On 16 Aug. 1905, at a convention in Regina, the 37-year-old Scott was unanimously chosen leader of the provincial Liberal Party. In his acceptance speech he promised he would provide open and clean government. Saskatchewan formally came into existence on 1 September, and Amédée-Emmanuel Forget*, the lieutenant governor of the North-West Territories, became the viceregal representative of the new province. His first task was to pick a premier. His choice of Scott was controversial because many expected Haultain to continue. Laurier merely said that the decision was Forget’s and that he had no influence, but sceptics in the west believed otherwise.

Scott quickly began the work of governing. Sworn in on the 12th, his cabinet consisted of himself, William Richard Motherwell* (provincial secretary and minister of agriculture), James Alexander Calder* (treasurer and minister of education), and John Henderson Lamont (attorney general). The electoral boundaries of 25 ridings were set by the federal government, and Scott picked 13 December for the first election. Running on the optimistic slogan of “Peace, Progress, and Prosperity” – peace with Ottawa, progress in the development of the province, and prosperity for its people – he campaigned tirelessly that fall. Electors chose 16 Liberals, including Scott in Lumsden; 9 Provincial Rights members were returned under Haultain, who had crusaded against federal control of public lands and resources.

With settlers moving into Saskatchewan by the thousands, the Scott government faced many challenges, notably the fundamental processes of building an infrastructure. The province needed roads, railways, bridges, schools, jails, asylums, courthouses, telephone systems, and statutory frameworks for municipal government. A raft of enabling legislation, much of it initiated by Scott, was passed in the 11 years of his ministry. In addition to his duties as premier, he was responsible for public works (1905–12), railways (1906–8), municipal affairs (1908–10), and education (1912–16).

Two major projects in particular, both instances of Scott’s grand vision for Saskatchewan, captured the imagination of his government. His first big idea was to create a university, not just a local college, that would compete on the national and international stages. In 1907 the Legislative Assembly passed a statute to create the University of Saskatchewan. There was hot competition over its location and ultimately Saskatoon was chosen. (Scott was a keen proponent of distributing major institutions throughout the province.) Walter Charles Murray* from Dalhousie University in Halifax was hired as president. “This is a great country,” Scott said on first meeting the new appointee. “It needs big men with large ideas.” Murray, who would emphasize agricultural science and extension studies for rural students, filled the bill. A college of agriculture, which they both saw as an integral part of the university, formally opened in 1912 [see William John Rutherford*].

The other important project was the construction of a suitably grand building to house the government and the assembly. The chosen site was south of Regina, on the far side of the reservoir created in the 1880s by damming Wascana Creek. Designed by Edward* and William Sutherland Maxwell of Montreal, the new legislature was begun in 1909 and completed in 1912. Scott, who was responsible for the project as minister of public works, had wanted the structure to meet the province’s needs for years to come. Moreover, it had to be built to withstand the prairie’s extremes of heat and cold. At his request, it was fitted with a huge dome, so that Saskatchewan’s monument to British parliamentary democracy would be visible from a distance. The original budget was between $750,000 and $1 million, but with changes and additions the final cost exceeded $1.8 million. Scott maintained the expense was worthwhile. It is still the largest provincial legislative building in the country.

In his aspirations for the province, Walter Scott believed that, if immigrants settled on every quarter section of land in Saskatchewan, its population would surge to about 20 million within 20 years. The population did expand, from 257,763 in 1906 to 647,835 in 1916, and by 1925 the province was the third largest in the dominion population-wise, but Scott could not have foreseen the limitation in growth that would be brought about by the gasoline tractor and the development of larger farms, and by the drought and economic depression of the 1930s.

Agriculture was the cornerstone of his government’s economic priorities. Farmers felt vulnerable to the large railways and grain-elevator companies that conveyed their product to market. Long an opponent of the monopolistic CPR, Scott favoured more local lines in his province and the alternative services offered by the Grand Trunk Pacific and the Canadian Northern [see Charles Melville Hays*; Sir William Mackenzie*]. In 1909 his government passed important legislation supporting branch lines of both these railways. In Manitoba, to provide storage services, the government bought elevators [see Frederick William Green*], but Scott believed that public ownership was not the right approach. Saskatchewan, he reasoned, could ill afford to build these tall statements of prairie existence, and farmers would not feel they had a stake in government elevators. Instead, on the recommendation of a commission headed by Robert Magill*, in 1911 the government established the Saskatchewan Co-operative Elevator Company, which was farmer-owned and -operated. If people worked cooperatively with modest public assistance, Scott felt, great things could be accomplished. A second example of this approach was the rural telephone system begun in 1908. The government could not pay to build a complete system, but it could provide the telephone poles, leaving the farmers to form cooperative companies and do much of the installation. This work was carried out with great success under the direction of J. A. Calder.

Rural Saskatchewan was important to Scott for reasons beyond agriculture’s status as the province’s key industry. His government relied on electoral support in country areas. To sustain it, he brought farm leaders into his government. Like Scott, W. R. Motherwell, his first minister of agriculture, had been involved with the Territorial Grain Growers’ Association. George Langley, another influential leader, joined the cabinet in 1912 as minister of municipal affairs. Scott’s inclusionary approach worked, and the Liberals gained healthy majorities in the elections of 1908 and 1912, with Scott winning both times in Swift Current.

The tasks facing his government were not just buildings and agriculture. The century’s first decades were times of transformation and upheaval, and Scott, if seemingly slow, was sensitive to social demands. World War I increased the pressure for social change such as Prohibition and the franchise for women. On both issues, Scott had prevaricated. With an eye on the next general election he was determined not to outpace public opinion. Prohibition was instituted in northern Saskatchewan in November 1914. The war, however, forced further action. Prohibitionists argued, with patriotic fervour, that grain should be used to feed soldiers, not to make alcohol. In the spring of 1915 Scott’s administration moved to close Saskatchewan’s remaining liquor outlets and control sales through government-run stores. Total Prohibition, enacted provincewide in 1917 by the succeeding administration, did not last long after the war. As Scott had judged, popular opinion did not support the complete ban.

The Prohibitionists and suffragists often tended to be one and the same: if women could get elected and influence law-making, perhaps they could also curb alcoholic consumption. The government felt pressure from both groups. Scott had encouraged women first to canvass the province to build consensus and gain electioneering skills. John Ernest Bradshaw*, a persistent critic of alleged malfeasance in Scott’s party, raised the issue of suffrage in the assembly in 1912. Pressure continued through the petition campaign headed by Violet Clara McNaughton [Jackson*] in 1913 and sponsored by the Saskatchewan Grain Growers’ Association. In wartime, women stressed their familial sacrifices and support and asked how foreign-born male immigrants could vote when they could not. The decision by Manitoba in 1915 to grant the vote to women [see Winona Margaret Flett*] finally spurred Scott to take action. On 14 Feb. 1916 he announced that his government would grant the vote and the legislation received assent a month later, making Saskatchewan the second province to enfranchise women.

The Great War prompted a surge of Anglocentric patriotism in Saskatchewan, which in turn intensified nativist reaction to the province’s ethnic immigrants. This reaction took solid hold in the debate over education, the portfolio held by Scott from 1912 to 1916, and quickly overshadowed achievements in the field. School districts had been organized at a rapid rate, a provincial superintendent of education appointed in 1912, and a normal school opened in Regina in 1913. In addition, school-funding problems had been addressed, and in this area problems had flared. In November 1912, to correct errors in a court ruling on assessments and funding, Scott introduced amendments to the School Act that required the religious-minority ratepayers to support the separate school in their district. Passed in January, the measures generated a sweeping backlash, made worse by wartime sensitivities, against separate schools, the Catholic Church, non-English instruction, and European immigrants. The tolerant Scott nevertheless moved forward in his development of the education system. Further amendments to the School Act, in 1915, included a clause to confirm existing practices of bilingual instruction. This amendment only refuelled the debate. The premier withdrew it on the grounds that such instruction would persist, but attacks on Scott and his government continued, hastening the worrisome decline of his health and political control.

Even though the Liberals had embarked on many successful initiatives, privately Walter Scott had a dark cloud over his head. From 1906 until his retirement as premier in 1916, he had to leave the province every year for up to six months. Although key decisions and programs had to be delayed until his return, the public never became overly concerned about his absences. The party was able to cover up the fact that Scott was away so much, and deputy premier J. A. Calder, who was content to stay in the background, capably looked after day-to-day government.

Scott suffered from depression, and he found that he needed to escape the long, dark nights of Saskatchewan’s winters. At this time there were no medications to help the depressed. Instead, it was believed that special diets, massage, steam baths, and seaside vacations in warm climates were the answer. Scott thus travelled to the Caribbean and the Mediterranean and consulted doctors around the world, but his illness could not be cured. To help cope, he also took up horseback riding and golf, outdoor activities meant to promote relaxation. An avid baseball fan since his days as a player in Regina in the 1880s, he read newspapers from all over North America for their sports stories and political coverage. Photographs of Scott while cruising, as in public in Saskatchewan, show a moustached, well-dressed man of medium height. His wife, who rarely accompanied him abroad, remained in the background but patiently supported him in politics and through the depths of his illness and long absences.

The rest and travel did seem to do Scott some good, and each spring he would return to Saskatchewan filled with optimism and fresh ideas about what his government could do to improve the province. His study of German banking in 1912, for instance, led to an examination of low-interest loans for farmers and then, the following year, to the incorporation of the Saskatchewan Co-operative Mortgage Association. Gifted with an ability to relate to people and make them feel he cared, he was a prolific letter writer when well, and he gained in popularity as the years went by. The Scott–Calder team was a good one. However, as Winnipeg journalist John Wesley Dafoe* privately observed in 1916, from at least 1912 “Walter has been neither physically nor mentally capable of carrying the premiership.”

The challenges faced by Scott peaked during the war years. In the winter of 1915–16 he had been stung by vituperative attacks on separate schools in sermons by his Presbyterian pastor in Regina, Murdoch Archibald MacKinnon. Scott insisted on taking this nasty spat into the assembly on 24 February. There, uncharacteristically, he flayed MacKinnon and then he bolted for the Bahamas. At the same time his government was facing accusations of widespread scandal, many of them emanating from the tenacious J. E. Bradshaw. Three commissions of inquiry were named in March to investigate bribery and liquor-licence charges, fraudulent highway contracts, and the maladministration of some public buildings and the telephone department. But there was no strong spokesman present constantly to defend the government’s record. Though Calder did his best, Scott was often away or, when at home, unstable. He had become a liability to the party. On 20 Oct. 1916 he resigned as its leader and as premier, and was succeeded by William Melville Martin*. As it turned out, the commissions found no fault with Scott and his cabinet, though several officials and mlas were punished.

Walter Scott lived for another 21 years after his retirement, but he was never able to return to politics or take up any useful employment. Buoyed up by court support in 1918 of his 1913 amendments, he revisited the dispute with MacKinnon, although such former associates as George Langley counselled him to back off. He tried to resume writing for his newspaper, the Moose Jaw Evening Times. In a letter published on 25 Nov. 1918 he opposed the federal Union government of Sir Robert Laird Borden, but journalism was no longer Scott’s calling. The following year, when, refreshed by a trip, he campaigned for his old colleague W. R. Motherwell in a federal by-election, it was clear from Scott’s criticism of the involvement of the Saskatchewan Grain Growers’ Association, which had opposed him in the schools debate, that a chasm had opened in his relations with agrarian leaders. His depression seemed to increase; life became dreary. He and his wife had retired to Victoria, and Scott virtually disappeared from the Saskatchewan political scene. In 1925 the University of Saskatchewan awarded him an lld in absentia. On 4 Feb. 1936 he was committed to Homewood Sanitarium, a private psychiatric hospital in Ontario for better-off patients. He died there alone two years later, from a blood clot.

The newspapers in Saskatchewan announced his passing but made no mention of the hospital. The Liberal Party, which had largely concealed his true psychological condition while he was in power, was equally determined to prevent the sad circumstances of his final years from becoming known in Saskatchewan. Scott was buried, not in the province of his birth or in the province he had helped to create, but in Victoria, alongside his wife.

The fruits of Walter Scott’s labours in education, agriculture, and public policy continue to be harvested in Saskatchewan today, though few remember who planted the seeds.

AO, RG 80-0-1861, no.36176. G. L. Barnhart, “Peace, progress and prosperity”: a biography of Saskatchewan’s first premier, T. Walter Scott (Regina, 2000). Canadian annual rev. CPG. [W. A.] Waiser, Saskatchewan: a new history (Calgary, 2005).

Cite This Article

Gordon Barnhart, “SCOTT, THOMAS WALTER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 14, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/scott_thomas_walter_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/scott_thomas_walter_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gordon Barnhart |

| Title of Article: | SCOTT, THOMAS WALTER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2013 |

| Year of revision: | 2013 |

| Access Date: | December 14, 2025 |