Source: Link

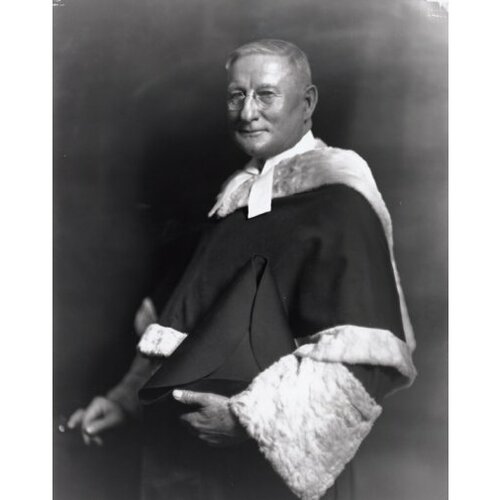

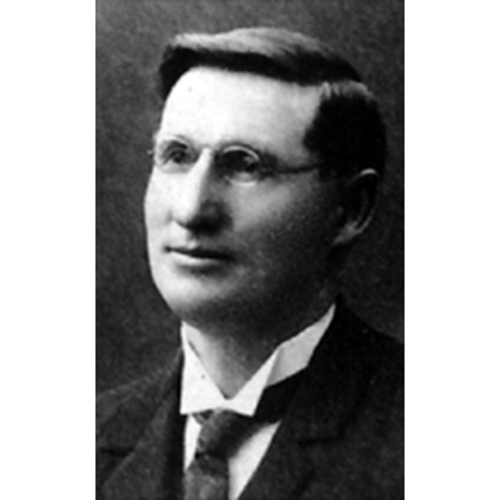

LAMONT, JOHN HENDERSON, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 12 Nov. 1865 near Horning’s Mills, Upper Canada, son of Duncan Carmichael Lamont and Margaret Robson Henderson, farmers; m. 21 Oct. 1899 Margaret Murray Johnston in Toronto, and they had a son, who died young, and a daughter; d. 10 March 1936 in Ottawa.

John Henderson Lamont’s father emigrated from the Isle of Mull and passed on a Scottish love of education to his son, who attended high schools in Brampton and Orangeville, Ont., before studying at the University of Toronto (ba 1892, llb 1893). After further law studies at Osgoode Hall, John was called to the Ontario bar in 1895. He practised in Toronto for four years and then left to seek better opportunities in the North-West Territories. His hopes were soon gratified. On 27 July 1899 he was enrolled as a member of the Law Society of the North-West Territories and he established an office in Prince Albert (Sask.) that year. In 1902 he would be appointed crown prosecutor and three years later he would be made a kc.

In 1904 Lamont was elected to the House of Commons as a Liberal for the territories’ Saskatchewan constituency. When Saskatchewan became a province the following year, he resigned his federal seat, and on 12 Sept. 1905 he was sworn in as attorney general in Premier Thomas Walter Scott’s inaugural four-member cabinet. In the provincial election held on 13 Dec. 1905 he was returned to the Legislative Assembly for the district of Prince Albert City. His relations with Scott, who had also served as a Liberal mp in Ottawa, were excellent. As attorney general, Lamont oversaw the enactment of the statutory framework for the legislature, the courts, and the municipalities. He is also credited with establishing the use of the Torrens system of land registration [see Louis William Coutlée*]. Justice Clifford Sifton Davis remarked that, although Lamont did not found the system, which was first introduced in Australia, “the interpretation and application of it according to the laws of this country was the work of Lamont” and, he added, of William Ferdinand Alphonse Turgeon*, Lamont’s successor.

An unfulfilled aspiration of Lamont’s during his time in office was to have the new province’s boundaries changed to include the port of Churchill on Hudson Bay. Lamont contended that he had a verbal agreement with Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* that Churchill would be given to Saskatchewan, but when the boundaries of Ontario and Manitoba were extended northward in 1912, after Laurier’s defeat, the port went to Manitoba. Saskatchewan was destined to remain landlocked.

After a term of two years, Lamont resigned as attorney general and mla on 23 Sept. 1907 as a result of his appointment to the Supreme Court of Saskatchewan. This court was superseded by the new Court of King’s Bench and Court of Appeal on 1 March 1918. He was assigned to the latter along with Chief Justice Sir Frederick William Gordon Haultain* and justices Henry William Newlands and Edward Lindsay Elwood.

Because Lamont served in the Court of Appeal during the Prohibition era, he dealt with a number of cases that fell under the provisions of the temperance acts of the day. In 1921 he was in favour of overturning the conviction of a drink vendor who had unwittingly come into possession of alcoholic beverages. He argued not only that the appellant was innocent of an intention to violate the legislation, but also that he could not reasonably have been expected to examine his stock when doing so would have destroyed it; however, the guilty verdict was upheld by the court majority. In another case, heard in 1923, the judges agreed that a cold-storage company that had been holding alcohol, which it believed to be temperance beer (or near-beer), had acted in good faith and that the conviction should therefore be quashed. Lamont maintained that a guilty verdict would be unjustified because the appellant could not be expected to test the contents of the bottles.

On 2 April 1927 Lamont was appointed a puisne judge on the Supreme Court of Canada, the first Saskatchewanian to serve on this court. The following year, in the landmark persons case, he agreed with Chief Justice Francis Alexander Anglin that section 24 of the British North America Act did not imply the inclusion of women in the class of “qualified persons” eligible to be summoned to the Senate. Furthermore, it was held that the words used in the act must retain the same meaning in 1928 as had been intended in 1867, when women could neither vote nor hold public office. A year later, however, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, then the court of highest appeal for Canadian cases, reversed the decision [see Emily Gowan Ferguson]. In the radio reference case, decided in 1931, Quebec had sought to know whether the provinces had the jurisdiction to regulate radio communication. Although the majority of the court held that such communication was exclusively a federal responsibility, Lamont and Thibaudeau Rinfret* dissented, arguing that the receiving apparatuses were to be regarded as “local works” and therefore under the control of the provinces.

Because of illness, Lamont was frequently unable to sit during the 1935 session, and he died early in 1936. Personal accounts focus almost exclusively on his political and legal careers. Known to have inherited the robust Presbyterianism of his Scottish forebears, he enjoyed golfing and gardening, and was a member of the Assiniboia Club for more than 20 years. His daughter, Katharine Johnston Lamont, a graduate of her father’s alma mater as well as of the University of Oxford, became head of the history department at Bishop Strachan School in Toronto.

John H. Lamont was an able if traditional jurist who tended to assess legal issues narrowly, taking, for example, a literalistic approach to the BNA Act. He was more creative, perhaps, in his role as a path-breaking attorney general than in his work on the judicial tribunals to which he was appointed.

The DCB wishes to thank Mr Iain Mentiplay for his assistance in verifying some of the information in the text.

AO, RG 80-5-0-265, no.2419; RG 80-8-0-1648, no.10882. Canadian Plains Research Center, Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan: a living legacy (Regina, 2005). W. H. McConnell, Prairie justice (Calgary, 1980). R. v. Ping Yuen (1922), Dominion Law Reports (Toronto), 65: 722–34. R. v. Regina Cold Storage and Forwarding Co., Ltd, [1924] Dominion Law Reports, 2: 286–96. Reference re “Persons” in S.24 of the B.N.A. Act, [1928] Canada Supreme Court Reports (Ottawa): 276–304; reversed (sub nom. Edwards v. A. G. Can), [1930] Dominion Law Reports, 1: 98–113 (Privy Council). Reference re Regulation and Control of Radio Communication, [1931] Canada Supreme Court Reports: 541–78; affirmed, [1932] Dominion Law Reports, 2: 81–88 (Privy Council). W. A. Waiser, Saskatchewan: a new history (Calgary, 2005).

Cite This Article

Howard McConnell, “LAMONT, JOHN HENDERSON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 27, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lamont_john_henderson_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lamont_john_henderson_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Howard McConnell |

| Title of Article: | LAMONT, JOHN HENDERSON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2015 |

| Access Date: | April 27, 2025 |