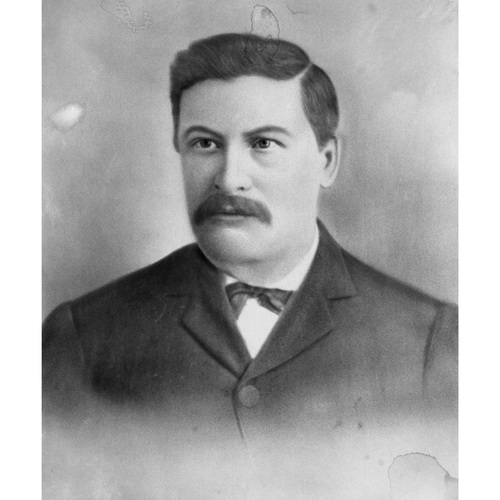

![James Francis Sanderson, Medicine Hat, Alberta. [ca. 1880s]. Image courtesy of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta.

Original title: James Francis Sanderson, Medicine Hat, Alberta. [ca. 1880s]. Image courtesy of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta.](/bioimages/w600.11442.jpg)

Source: Link

SANDERSON, JAMES FRANCIS, interpreter, businessman, rancher, and author; b. 23 March 1848 in Athabasca Landing (Athabasca, Alta), son of James Sanderson and Elizabeth Anderson; m. 16 Sept. 1872 Maria McKay of the Red River settlement, Man., and they had two sons and a daughter; d. 8 Dec. 1902 in Medicine Hat (Alta).

James Sanderson’s life spanned the exciting early years of western Canadian development. He was born into a family which had a long association with the Hudson’s Bay Company. His father worked out of York Factory (Man.) for nearly a decade as a bowsman and steersman for the company. His mother was the daughter of country-born trader John Anderson. James Sr died young and Elizabeth married William Sunderland, a member of another family with close HBC connections. With her children, she and William settled at Portage la Prairie (Man.). Here, young James received a rudimentary and sporadic formal schooling. He did have the opportunity to accompany his family on several buffalo-hunting expeditions across the plains in the late 1860s. This frontier experience would prove valuable in his later years.

By February 1870 word of a Métis insurrection at the Red River settlement had spread through Assiniboia. In that month James, his elder brother, George William, and other young men of the Portage la Prairie district joined the militia group under Charles Arkoll Boulton* that set out to release the men whom Louis Riel*’s people had incarcerated in Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg). Captured and imprisoned in the fort along with Thomas Scott* and others, Sanderson endured crowded, cold quarters and poor food during a month of internment.

Sanderson married Maria McKay in 1872. She was the daughter of Edward McKay, a freeman and patriarch of a large, country-born family. That year the McKay clan settled in the Cypress Hills but they continued their buffalo hunting, and with them Sanderson travelled the western prairies, learning much from his father-in-law as they went. In 1875 a North-West Mounted Police detachment under Inspector James Morrow Walsh established a post, Fort Walsh (Sask.), near the McKays’ headquarters. Sanderson served the police as scout, meat and hay procurer, and interpreter, being able to speak French and Cree. In 1877 he brought in a small herd of cattle from Montana. They were essential to his meat-supply contract with the police since the buffalo were rapidly disappearing.

With the approach of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1882, the McKays and Sandersons moved to Medicine Hat. Sanderson continued to assist the police, serving the Medicine Hat detachment as interpreter and liaison with the native people. When railway construction crews arrived in June 1883, he hired on as freighter and general contractor. He located land near the village where he could run his cattle herd and race his horses, and he soon became an ardent promoter of racing.

As he recognized the economic opportunities awaiting him, Sanderson quickly transformed himself into an entrepreneur. He operated a bull herd for the ranchers of the area: every spring and autumn he collected hundreds of bulls from district ranches and herded them onto his own rangeland. From hunting buffalo he turned his energies to gathering their bleached bones, which were used in the east for fertilizer. During the late 1880s, he hired crews of young Métis to scour the prairies. The industry was a lucrative one in those years, Sanderson himself clearing $1,100 during the 1887 season alone. (The year before, he had brought down the last wild buffalo in the district, he claimed.) He turned his hand to many other activities as well. He became the agent for the local coalmine in 1889, held the ice contract for the CPR after 1892, and became wolf inspector for the district in 1894. His responsibilities in the latter post would have been to keep a tally on the wolf population and to patrol the district to discourage bounty hunters from using poisoned bait. In the 1890s he built and operated a large livery stable in the town. He continued to offer draying services and did road contracting. His numerous pursuits earned him a comfortable lifestyle.

Whatever spare time Sanderson found, he tended to invest in a narrow range of interests. He attended the Church of England. A founder and president of the agricultural society in 1893, he served as president of the local stock growers’ association from 1896 to 1898. He promoted irrigation for the district and in 1894 headed the irrigation league.

Sanderson was a heavy-set, handsome, and robust man whose features strongly suggested his native heritage. His skills and energy brought him the respect of the community, which saw him as one of the last of the great frontiersmen. Considered an authority on native cultures, he wrote a series of articles in 1894 entitled “Indian tales of the Canadian prairies.” These stories, generally based on events that happened between 1850 and 1870, recounted the legends of bold warriors and well-remembered battles between the Cree and Blackfoot tribes. Because the Medicine Hat vicinity had always been a favourite spot for Indians, there were many references to it, and the series, published in the Medicine Hat News, was popular reading among local settlers. Sanderson’s sensitivity to the plight of the natives led him to become an advocate for their cause. In 1896, for example, he circulated a petition in the Medicine Hat district on behalf of a group of Cree who wandered between Medicine Hat and Maple Creek (Sask.). The purpose of his successful crusade was to persuade the dominion authorities to locate a reservation for these unfortunate people.

James Sanderson is a good example of a country-born frontiersman who was able to adapt to an agricultural economy. Many of his compatriots who were of mixed blood, or had married native or country-born women, remained fringe elements in the society of the North-West Territories in the late 19th century. Sanderson, however, earned respect as an astute businessman, a solid citizen, and a glamorous symbol of a bygone romantic age. He never tested the full extent of his community’s tolerance by seeking public office.

James Francis Sanderson’s “Indian tales of the Canadian prairies,” originally printed in the Medicine Hat News (Medicine Hat, [Alta]) in March and April 1894, was republished with illustrations by W. B. Fraser in Alberta Hist. Rev. (Calgary), 13 (1965), no.3: 7–24. An autobiography by his brother dating from around 1934 is preserved in a typescript at PAM, MG 9, A107, and has been published as “The ‘Memories’ of George William Sanderson, 1846–1936,” ed. I. M. Spry, in Canadian Ethnic Studies (Calgary), 17 (1985), no.2: 115–34.

Medicine Hat Museum and Art Gallery, Arch., Biog. file, J. F. Sanderson; M.69.125.25 (Margaret Ireland coll., J. F. Sanderson death notice); M.86.21.1 (L. M. Modien, “The McKay family: people of the Little Bearskin” (research paper prepared for Fort Walsh National Hist. Park, Sask., 1986)), F9; photographs of J. F. Sanderson. PAM, MG 12, B1, no.164 (report of Edward McKay, 21 May 1873). Medicine Hat News, 22 March, 15 Nov. 1894; 27 Feb., 26 March 1896. Medicine Hat Times, 24 Oct. 1889, 21 Jan. 1892. W. H. McKay, “Early days of Medicine Hat” and “The story of Edward McKay,” Canadian Cattlemen (Calgary), 12 (1949–50): 28–29, 32–33; 13 (1950), no.3: 48–49, 52–53; 14 (1951), no.7: 16–17, 20–21, 29; and 10 (1947–48): 76–77, 100–5, respectively. J. W. Morrow, Early history of the Medicine Hat country ([Medicine Hat], 1923; repr. 1964). Morton, Manitoba (1957).

Cite This Article

L. J. Roy Wilson, “SANDERSON, JAMES FRANCIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 23, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sanderson_james_francis_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sanderson_james_francis_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | L. J. Roy Wilson |

| Title of Article: | SANDERSON, JAMES FRANCIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 23, 2025 |