WALSH, JAMES MORROW, NWMP officer, businessman, and government official; b. 22 May 1840 in Prescott, Upper Canada, one of the nine children of Lewis Walsh, a ship’s carpenter, and Margaret Morrow; m. 19 April 1870 Mary Elizabeth Mowat, and they had one daughter; d. 25 July 1905 in Brockville, Ont.

Almost nothing is known about James Morrow Walsh’s early life. The pattern of his employment before age 30 suggests a restless and romantic personality. After leaving school, where he had been an indifferent student but had excelled at sports, Walsh tried his hand at being a machinist, working on the railway, clerking in a dry-goods store, exchange brokering, and managing a hotel. Like many other young men of the period he was drawn to the military life, and he took advantage of the few opportunities for it that existed in British North America, attending the training courses offered to militia officers and serving during the Fenian raids of 1866.

During the Red River disturbances of 1869–70 [see Louis Riel*], Walsh obtained one of the highly prized commissions in the 2nd (Ontario) Battalion of Rifles in the Red River expeditionary force. At the last moment he turned down the position, probably because of his marriage on 19 April 1870 to Mary Elizabeth Mowat. The fact that the couple’s only child was born six months later suggests that the union was not entirely planned.

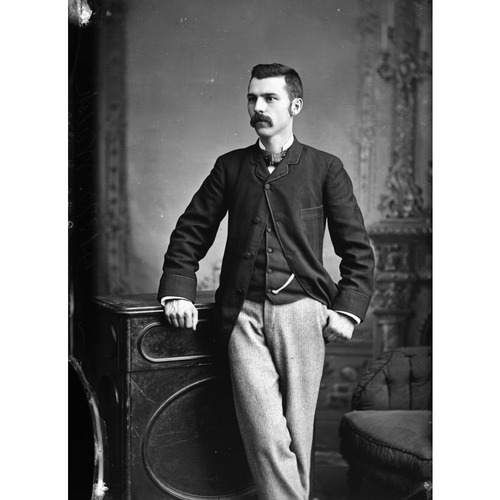

Walsh had excellent political connections with the governing Conservative party in Ottawa. In May 1873 he was offered a commission as superintendent and sub-inspector in the mounted police force being organized for the North-West Territories. After his appointment in September, he helped recruit members of the first contingent and accompanied them to Winnipeg. Walsh impressed Commissioner George Arthur French* sufficiently that he was appointed acting adjutant and riding-master at Winnipeg and promoted inspector in the spring of 1874. The following year he became Superintendent Walsh when the police changed their rank designations. During the strenuous march west in the summer of 1874 Walsh had been given the kind of assignments that make it clear he was regarded as the most reliable of the six troop leaders.

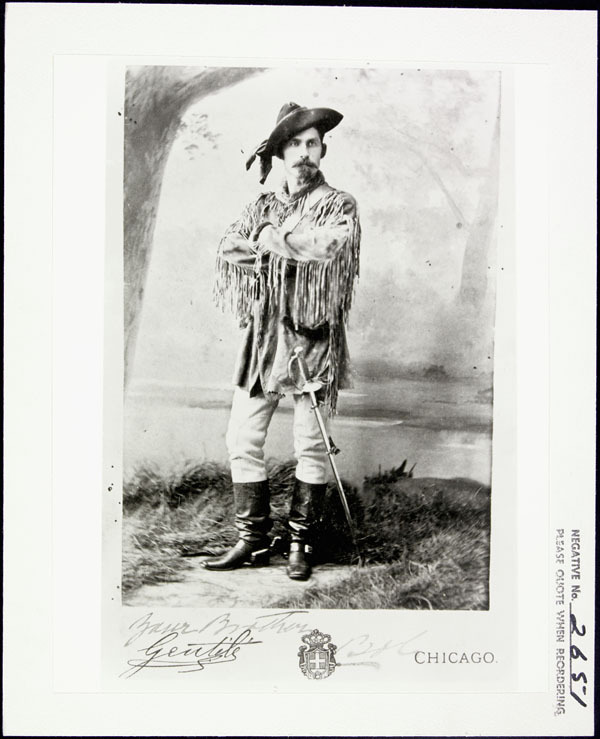

This status was confirmed in the spring of 1875, when Walsh was sent to the Cypress Hills in command of B Division to establish an independent post which he was allowed to name for himself. Fort Walsh (Sask.) was to be the most important North-West Mounted Police establishment for the next seven years. Its significance was largely due to the fact that after the defeat of George Armstrong Custer at the battle of the Little Bighorn River in June 1876, Sitting Bull [Ta-tanka I-yotank*] and several thousand Sioux had taken refuge in Canada. Responsibility for handling this delicate and dangerous situation fell in the first instance upon Walsh. He quickly established a relationship of trust with Sitting Bull and other Sioux leaders. Although the Sioux outnumbered the police many times, they kept the peace within Canada and refrained from making raids across the border. Walsh basked in the glow of American newspaper stories that referred to him as “Sitting Bull’s boss.”

Keeping the Sioux peaceful was only part of Walsh’s mandate. The Canadian government was extremely anxious to encourage them to return to the United States. As the years passed and Sitting Bull showed no sign of readiness to return, Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* began to suspect that Walsh was lukewarm in his efforts to persuade the Sioux to leave, and then that the superintendent was actively working to prevent their leaving. Walsh was transferred to Fort Qu’Appelle (Sask.) in 1880 and later in the year sent to Brockville on leave to get him out of the way. He was not allowed to return to his command until 1881, after Sitting Bull had left for the United States. Two years later he was forced to resign.

Walsh was understandably bitter about his treatment. He had handled a dangerous situation without much more in the way of resources than courage and force of personality. To expect him to persuade the Sioux to leave quickly was asking for a miracle. The Sioux were anxious to remain permanently and the United States authorities were happy to let them stay. Only time and gradual impoverishment created the kind of pressures necessary to resolve the situation. Walsh had nevertheless antagonized his superiors by behaving ostentatiously for the press. He further weakened his credibility within the force by becoming too sympathetic to the native predicament and too close to the Sioux. He appears to have had a child with a Blackfoot woman and relationships with Sioux women. Given the standards of the time, this behaviour was sufficient in itself to bring about his removal.

Almost nothing is known about Walsh between 1883 and 1897. Upon leaving the NWMP he moved to Winnipeg, where he entered the coal business with two partners. He left this venture before long and became manager of the Dominion Coal, Coke and Transportation Company, which exploited the Souris coalfields. At some time he became a close friend of the rising Liberal politician Clifford Sifton*. When the federal Liberals came to power in 1896 Walsh lost no time in writing for Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier* a long memorandum explaining why the NWMP should be drastically reduced in size.

Sifton gave Walsh his revenge on the NWMP in a different fashion. The Klondike gold-rush was well under way by the summer of 1897 and had become the major focus of the activities of the police. In August, Walsh was made commissioner of the Yukon territory and reinstated as a superintendent; in October he was given command of the NWMP in the territory. Under instructions from Sifton, who was minister of the interior, Walsh communicated directly with Ottawa, bypassing police headquarters in Regina and making the Yukon contingent virtually an independent force.

Walsh’s appointment was fiercely resented within the NWMP, but no trouble developed because he resigned in the spring of 1898. His leaving had more to do with his political and administrative difficulties as commissioner than with his police duties. Mining regulations were a tangled mess, and he showed no aptitude for sorting things out. Moreover, by allowing members of his staff to file claims Walsh left his administration open to political attack. When the criticisms began he immediately resigned, and he had to be persuaded to stay until his replacement, William Ogilvie, arrived. Walsh’s retirement may have been in part due to ill health. He returned to Brockville and remained there until his death.

James Morrow Walsh had been an important actor in several of the most dramatic episodes that marked the development of western Canada. Throughout his life he was at his best in situations that demanded physical activity and face-to-face confrontation. More complex and intellectually demanding problems revealed his limitations.

NA, MG 26, G: 7090–91; MG 27, I, 134; RG 18, 3, file 48A–75; 9, file 69–76; 12, files 147–83, 460–80; 148, file 137–98; 616, letter 86; 1004, file 16; 1974, letters 349–52, 354–56, 369, 2342, 2464, 2479, 2567–69, 2581, 2585, 2697, 2760; 1975, letters 40, 345, 531, 620, 674, 967, 977, 2956, 2958; 2231, letters 7, 9. PAM, MG 6, A1. Royal Canadian Mounted Police Headquarters (Ottawa), Hist. Sect., J. M. Walsh service file. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Hall. Clifford Sifton, vol.1. [J. W.] G. MacEwan, Sitting Bull: the years in Canada (Edmonton, 1973). R. C. Macleod, The NWMP and law enforcement, 1873–1905 (Toronto, 1976). Joseph Manzione, “I am looking to the north for my life” – Sitting Bull, 1876–1881 (Salt Lake City, Utah, 1991). W. R. Morrison, Showing the flag: the mounted police and Canadian sovereignty in the north, 1894–1925 (Vancouver, 1985). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.2. C. F. Turner, Across the medicine line (Toronto, 1973); “James Walsh: frontiersman,” Canada: an Hist. Magazine (Toronto), 2 (1974–75), no.1: 28–42. J. P. Turner, The North-West Mounted Police, 1873–1893 . . . (2v., Ottawa, 1950), 1.

Cite This Article

Roderick C. Macleod, “WALSH, JAMES MORROW,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walsh_james_morrow_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walsh_james_morrow_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Roderick C. Macleod |

| Title of Article: | WALSH, JAMES MORROW |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | April 26, 2025 |