Source: Link

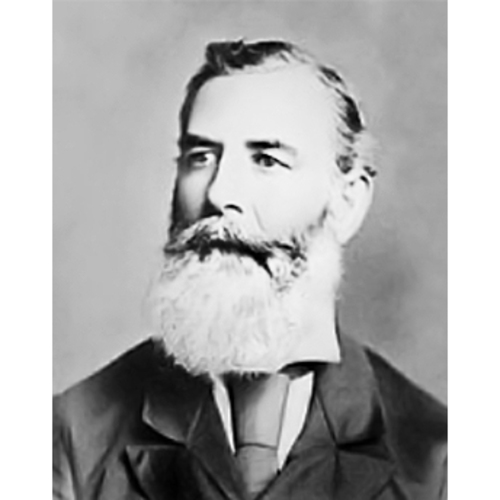

CANNIFF, WILLIAM, physician, medical educator, author, school administrator, and civil servant; b. 20 June 1830 in Thurlow Township, Upper Canada, son of Jonas Canniff and Letitia Flagler; m. first 20 June 1857 Grace Hamilton (d. 1858), and they had a son; m. secondly 15 Sept. 1859 Elizabeth Foster (d. 1908) in Toronto, and they had six sons and a daughter; d. 18 Oct. 1910 in Belleville, Ont.

A grandson of late loyalist settlers on the Bay of Quinte, William Canniff grew up in relative affluence on the family farm north of Belleville. (His father and elder brothers also owned and operated a grist-mill and a sawmill.) As the youngest surviving child in a family of nine, he was able to persuade his Wesleyan Methodist parents to send him to Victoria College in Cobourg, after he had completed his primary education in local schools. In 1852 he enrolled in John Rolph*’s Toronto School of Medicine, where he would study under William Thomas Aikins* and Joseph Workman*. With medical education in transition from apprenticeship to formal classroom training, Canniff and his schoolfellows were encouraged to seek further clinical education in the United States during summer breaks and to continue their studies in Europe after qualifying to practise.

Following his successful examination by the Medical Board of Upper Canada on 2 Jan. 1854, Canniff attended the University of the City of New York, completed his medical degree, and served as a house-surgeon in New York until the spring of 1855. He studied next at St Thomas’s Hospital in London, England, and qualified for membership in the Royal College of Surgeons of England later in 1855. Drawn to military medicine, he passed the examinations of the British army’s medical board to obtain a commission as an acting assistant surgeon in the Royal Artillery. The end of the Crimean War in 1856 left him free to visit hospitals in Edinburgh, Dublin, and Paris. In 1857 he returned to Canada, married, and set up practice in the Belleville area.

After his wife’s death from tuberculosis the following year, he agreed to join the teaching staff at Rolph’s school in Toronto, which had become the medical faculty of Victoria College. Initially appointed an instructor in pathology, he quickly became a professor of surgery and one of the staff responsible for serving clients at the dispensary Rolph and his second wife had established in 1861. By late 1862, however, he found himself embroiled in conflict with Rolph over its use for clinical education and in March 1863 the 33-year-old teacher resigned under duress.

Canniff had remarried in 1859 and was now left without a secure economic base for his growing family. The outbreak of the American Civil War had led to his drilling with the militia during the Trent affair [see Sir Charles Hastings Doyle*]. But it was to the Army of the Potomac that Canniff, who had visited Northern field hospitals in 1862, turned following his resignation. In May 1863 he received a surgeon’s commission with the army. His service was brief, however, for in June he resigned and returned to Belleville, to re-establish his practice. He subsequently published one of the first Canadian medical textbooks, A manual of the principles of surgery, based on pathology for students (Philadelphia, 1866); helped care for the wounded after the Fenian raid at Ridgeway in 1866 [see Alfred Booker*]; attended the International Medical Congress of 1867 in Paris, where he presented a paper on tuberculosis mortality among North Americans; and participated in the organizing meeting of the Canadian Medical Association in October of that year.

The early 1860s had witnessed the first stirrings of Canadian nationalism, and in 1861–62 Canniff had participated in attempts with George Coventry* and others to set up an Upper Canadian historical society. In the years that followed he completed the research and writing of his History of the settlement of Upper Canada (Ontario), with special reference to the Bay Quinte (Toronto, 1869), a project he claimed to have undertaken in 1862 at the instigation of the short-lived society. In this monumental study, Canniff’s developing interests in loyalist history and “the future prospects of the Dominion” fused, producing a distinctly British Canadian sense of nationality. The Red River rebellion of 1869–70 [see Louis Riel*] led to his active involvement with his brother-in-law William Alexander Foster* in what would become the Canada First group. An ardent believer in Canada’s northern destiny, Canniff helped organize Ontario’s opposition to the murder of Thomas Scott* at Red River (Man.) and became president of the North West Emigration Aid Society in August 1870. This society pressured the federal government of Sir John A. Macdonald* for a dominion lands policy that would attract Ontario farmers to the west and ensure that it reflected the new national values. In 1872 Canniff published in Toronto his History of the province of Ontario . . . , which, like his history of Upper Canada, he dedicated to Macdonald. A year later, however, the literary surgeon assisted Foster in organizing the Canada First party as an antidote to partyism, an example of which was the Pacific Scandal. Canniff’s pamphlet Canadian nationality: its growth and development (Toronto, 1875) was an impassioned plea for a pure Canadianism that would allow Canada to take its rightful place as an equal partner in the British empire.

In the medical field Canniff’s generation of doctors had begun in the 1860s to develop a more professional approach to education and practice [see William Thomas Aikins]. Journals, societies, and alumni associations were established to promote cohesion among orthodox practitioners, whose status was being challenged by splinter groups such as homoeopaths and eclectics [see Robert Dick*]. Conscious of John Rolph’s declining health and the imminent reestablishment of the medical faculty of Trinity College, which threatened his alma mater, Canniff returned to Toronto in 1868 to become professor of surgery and sub-dean of the medical faculty at Victoria. The following year he was appointed to the staff of the Toronto General Hospital and in 1870 he was made a consulting surgeon to the Toronto Eye and Ear Infirmary. When Rolph was forced to retire in 1870, Canniff was appointed dean. In spite of a dynamic program to construct a new school near the TGH, Victoria lost students, and the revenue it needed to survive, when many of its senior staff joined the rival Trinity Medical School. In 1874 Canniff’s career as a medical educator came to an end with the mass resignation of the Victoria staff, after the trustees of Victoria declined to support the reorganization of the medical school as a joint-stock company. He nevertheless retained his consulting position at the TGH and continued to present medical papers and publish articles describing his cases.

Canniff displayed both progressive and reactionary responses to aspects of medical professionalization. As chairman of the medical section of the Canadian Institute in 1870–71, he had begun to campaign for federal, provincial, and municipal public-health legislation. Like other conservative surgeons, he openly expressed, in articles and addresses from at least 1868, his scepticism about the effectiveness of Listerian antisepsis. Such opposition did not prevent his colleagues from electing him president of the Canadian Medical Association in 1880. From this position Canniff continued his long-running efforts to obtain federal funding for the collection of urban mortality statistics, in emulation of British practice. He was rewarded in 1882 when the Macdonald government introduced conditional grants for this purpose. To qualify, cities had to have local boards of health and salaried health officers. Appointed Toronto’s first permanent medical health officer on 12 March 1883, Canniff spent the next seven years slowly educating his fellow citizens in basic principles of sanitation and disease control. His efforts to modernize the city’s sewer system and waterworks, regulate its food supplies, and promote vaccination and isolation of the sick threatened many vested interests, including those of medical colleagues [see Alexander Milton Ross*]. Disillusioned and frustrated, he resigned on 17 Sept. 1890, but not before he had made preventive work an integral part of urban life.

In addition to his work as health officer, Canniff continued to pursue his interests in Canadian history and military medicine. In 1884 he presided over the loyalist centennial celebrations at Adolphustown and Toronto and started to collect the material for his final major work, The medical profession in Upper Canada, 1783–1850. . . (Toronto, 1894). At the time of the North-West rebellion, in 1885, he joined the Sisters of St John the Divine in setting up a hospital in Moose Jaw (Sask.) to serve the wounded from Fish Creek – a group that included his eldest son, William Hamilton.

After his resignation from the medical officership, Canniff tried to rebuild his private practice but was unsuccessful as a result of the depression of the early 1890s and, presumably, his traditional approach to curative medicine. By July 1894, having failed to obtain a federal position as a quarantine officer, Canniff had left Toronto and was starting up in the Muskoka region. Family lore suggests that alcoholism contributed to his departure. In spite of these difficulties and increasing physical infirmity, Canniff had retained his interest in Canadian history. In 1893–94 he served as chairman of the Canadian Institute’s historical section and in his keynote address of November 1893 he argued in favour of provincial funding for a museum to house artefacts of Ontario’s past. He contributed an article on the rebellion of 1837 in Upper Canada to John Castell Hopkins*’s Canada, an encyclopædia and sought republication of his Settlement of Upper Canada. Although the United Empire Loyalist Association of Ontario made him an honorary member in 1898, neither it nor the Ontario Historical Society had the money to support publication. Shortly after 1900 Canniff and his elder brother, Philip Flagler, returned to Belleville, where they lived together until William entered the newly opened House of Refuge in 1908. He died there two years later, leaving an estate valued at $500.

William Canniff’s story reflects some of the forces which shaped life in Ontario during the mid and late 19th century. His medical career demonstrates the growing importance of professional training and organizations, and the development of new areas of specialization, most notably public health. As a researcher and writer, he exemplifies the idealistic, visionary, and slightly naïve nationalism that characterized the confederation generation. Nevertheless, in the course of his historical work he preserved many important documents. In his history of Upper Canada he argued forcefully that “the importance of history cannot be questioned; the light it affords is always valuable, and, if studied aright, will supply the student with material by which he may qualify himself for any position in public life.”

In addition to the works mentioned in the text, William Canniff’s publications include The effects of alcohol upon the human system; an essay upon the cause, nature and treatment of alcoholism (Toronto, 1872); a second edition of the History of the province of Ontario (Toronto, 1874); “Fragments of the War of 1812: the Rev. George Ryerson and his family,” Belford’s Monthly Magazine (Toronto), 2 (1877): 299–308; and “An historical sketch of the county of York . . . ,” Illustrated historical atlas of the county of York . . . (Toronto, 1878), v–xxii. Three reprints of the historical atlas have been produced: ([Toronto], 1969), (Belleville, Ont., 1972), and ([Port Elgin, Ont., 1975]). Canniff’s History of the settlement of Upper Canada has been reprinted with an introduction by Donald Swainson as The settlement of Upper Canada (Belleville, 1971), and a reprint of his Medical profession in Upper Canada with a new introduction by Dr Charles G. Roland has been issued by the Hannah Institute for the Hist. of Medicine ([Toronto], 1980).

Reports by Canniff in contemporary medical journals include “Experience among some of the wounded who fell at the battle of Limestone Ridge, June 2nd,” “Tuberculization in various countries and its influence on general mortality,” and “Some remarks upon carbolic acid as a remedial agent in the treatment of wounds,” in the Canada Medical Journal and Monthly Record of Medical and Surgical Science (Montreal), 2 (1865–66): 529–34 and 4 (1867–68): 97–101 and 307–11, respectively.

Academy of Medicine (Toronto), W. T. Aikins papers. AO, F 1052, MU 2562, nos.7–9; F 1390; RG 8, I-6-B, 66: 78; RG 22, ser.340, no.3991; RG 80–8, no.1910-014494. NA, MG 25, 255; MG 29, D61: 1497–500; RG 5, B9, 68; RG 17, A I, 781, file 91191; 1662: 36. National Arch. (Washington), RG 94 (records of the Adjutant General’s Office), personal papers of medical officers and physicians prior to 1912, William Canniff file. St Thomas’s Hospital Medical School Library (London), “Pupil entry book,” no.991. UCC-C, Victoria Univ. Arch., 87.042V, items 27, 29, 32, 33b, 36. Daily Intelligencer (Belleville), 19 Oct. 1867. Daily Telegraph (Toronto), 21 Jan., 23 May 1870. Daily Times (Hamilton, Ont.), 26 Aug. 1870. Globe, 26, 31 Aug., 3 Sept. 1870. Hastings Chronicle (Belleville), 8 July 1857. Leader (Toronto), 9 July 1870.

Carl Berger, The sense of power; studies in the ideas of Canadian imperialism, 1867–1914 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1970). “Canada First movement: scrapbook of clippings relating to that movement and its founder and leader William Alexander Foster” ([Canadian Library Assoc. mfm., Ottawa], 1956). Canada Lancet, 15 (1882–83): 33–38. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. W. A. Foster, Canada First: a memorial of the late William A. Foster, q.c., intro. Goldwin Smith (Toronto, 1890). D. P. Gagan, “The relevance of ‘Canada First,’” JCS, 5 (1970), no.4: 36–44. R. D. Gidney and W. P. J. Millar, “The origins of organized medicine in Ontario, 1850–1869,” Health, disease and medicine; essays in Canadian history, ed. C. [G.] Roland ([Toronto], 1984), 65–95. J. J. Heagerty, Four centuries of medical history in Canada and a sketch of the medical history of Newfoundland (2v., Toronto, 1928). Lancet (London), 28 Feb. 1863: 251–52. H. E. MacDermot, One hundred years of medicine in Canada, 1867–1967 (Toronto, 1967). Heather MacDougall, Activists and advocates: Toronto’s health department, 1883–1983 (Toronto and Oxford, 1990); “‘Health is wealth’: the development of public health activity in Toronto, 1834–1890” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1982). Morgan, Bibliotheca canadensis. C. G. Roland, “The early years of antiseptic surgery in Canada,” Journal of the Hist. of Medicine and Allied Sciences ([New Haven, Conn.]), 22 (1967): 380–91. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.1. Toronto, City Council, Minutes of proc., 1883: 65; 1890, app.: 1959–60.

Cite This Article

Heather MacDougall, “CANNIFF, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/canniff_william_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/canniff_william_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Heather MacDougall |

| Title of Article: | CANNIFF, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | April 24, 2025 |