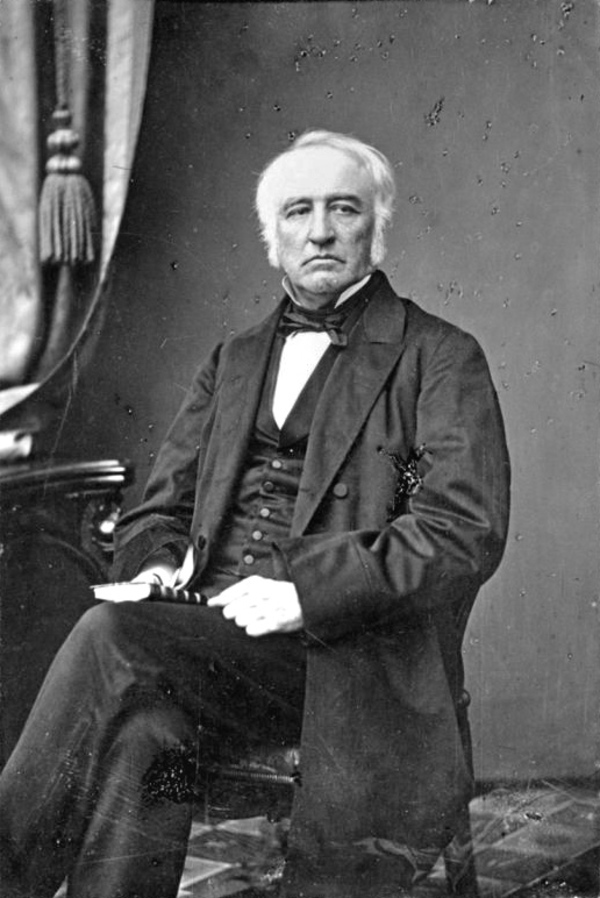

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

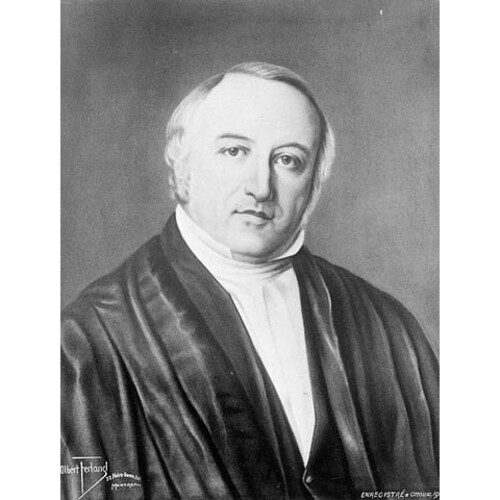

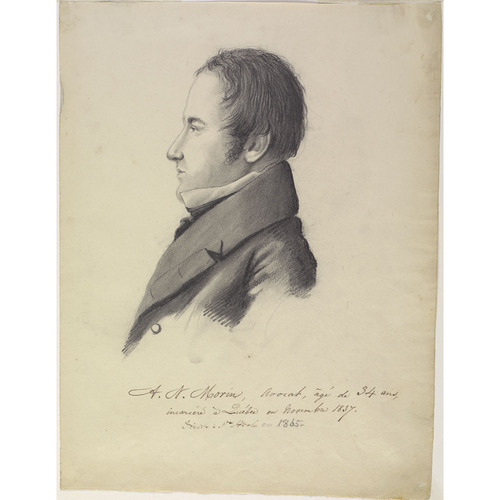

MORIN, AUGUSTIN-NORBERT, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 13 Oct. 1803 at Saint-Michel (Saint-Michel-de-Bellechasse), Lower Canada, eldest son of Augustin Morin, a farmer, and Marianne Cottin, dit Dugal; m. 28 Feb. 1843 Adèle, daughter of merchant Joseph Raymond, and sister of Joseph-Sabin Raymond*, the superior of the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe; they had no children; d. 27 July 1865 at Sainte-Adèle, Canada East.

Augustin-Norbert Morin was the eldest of 11 children who were the seventh generation of Morins in Canada. Despite his impressive height, Morin’s health was delicate and at an early age he was subject to violent attacks of rheumatism which forced him to restrict his activities. The Morin family was not well off, and Augustin-Norbertowed his classical education to the intervention of the parish priest of Saint-Michel, Abbé Thomas Maguire*. The latter discovered that the boy, to whom he was teaching the catechism, had remarkable talent and intelligence. The parish priest sent his protégé to the Séminaire de Québec in 1815. Morin was consistently successful in his studies, according to his teachers.

When he left the seminary in 1822 Morin hesitated between law and the priesthood but finally chose law. In debt and without financial means, he had to earn money in order to study. He began to work for Le Canadien, with a dedication disproportionate to the pittance he received. When the paper ceased publication in 1823, Morin went to Montreal to study law under Denis-Benjamin Viger. His financial worries were by no means over, however, for Viger was not exactly a generous man. The young clerk gave Latin and mathematics lessons in order to survive.

In 1825 he lashed out vociferously at Judge Edward Bowen on French language rights in the law courts of the province. The experience with Le Canadien, far from dissuading Morin from journalism, apparently prompted him to return to this profession. As his duties in Denis-Benjamin Viger’s office left him some leisure time, he decided to start a paper, which he named La Minerve. The first number was published on 9 Nov. 1826, but he had to suspend publication from the 29th of that month since the 240 subscriptions were not sufficient to cover expenses. Three months later Ludger Duvernay* bought the paper, and Morin undertook to continue as editor for six months. The founding of La Minerve was not received with joy by all Morin’s friends. Étienne Parent* questioned whether it was useful for the Parti Canadien to have two papers, Le Spectateur and La Minerve, and also turned down Morin’s offer that he become his parliamentary columnist: “the running of a paper may not be free of gall, but the debates are like the dregs.” For more than ten years, even after he was called to the bar and entered parliament, Morin contributed to La Minerve, supplying Duvernay with well-written perceptive articles on topics as varied as politics, judicial decisions, theatre, literature, and agriculture.

Morin was authorized to practise law in 1828, after taking final examinations under three judges from the district of Montreal: James Reid, chief justice of the Court of King’s Bench, and Louis-Charles Foucher and Norman Fitzgerald, of the same court. Dividing his time between legal practice and journalism, the young lawyer began to become familiar with the workings of the law, took an increasing interest in the public administration of the country with a view to better informing readers of La Minerve, and thus admirably prepared himself for entering politics.

On 26 Oct. 1830 the electors of Bellechasse chose Morin, one of their own, to represent them in the House of Assembly. His entry into politics might appear a paradox in the light of descriptions of him by contemporary politicians. One asserted that “He looked more liken bishop on a pastoral visit than a politician out for votes.” Morin remained true to his temperament, that of an assiduous worker: by 1831 he was able to inform Duvernay that he was a member of seven committees of the house, which required much work and prevented him from devoting time to his articles for La Minerve. In the house few topics failed to engage his interest. In 1831 he took steps on behalf of the widow of Dr Jacques Labrie*, former representative of the county of Deux-Montagnes, to obtain a special gift of £500 to allow her to publish a history of Quebec written by her husband. The next year Morin presented a petition on behalf of his friend Duvernay, who had been imprisoned for publishing statements attacking the composition of the Legislative Council. The sale of lands by Morin in the seigneury of Rivière-du-Sud exposed him to unsubstantiated accusations of embezzlement. Consequently, giving poor health as a pretext, the representative for Bellechasse resigned on 18 Dec. 1833. He was re-elected in a by-election on 25 Jan. 1834 by a majority of 41 votes. Re-election had ended the affair.

The year 1834 gave Morin the opportunity to distinguish himself. On 1 March the House of Assembly passed a resolution instructing the representative for Bellechasse to join Denis-Benjamin Viger in London to present the assembly’s petitions on the state of the province. The work he accomplished in London received the most laudatory comments, both from Louis-Joseph Papineau* and from the whole house. A rumour even circulated that he might be appointed a judge. But with the political climate already overheated, Morin could not avoid taking a stand: it was he who in 1834 drafted the 92 Resolutions.

In February 1836 Morin was still numbered among the moderates. But he rapidly adopted the position of Papineau’s group in their struggle against the Executive Council and over the question of supply bills. The representative for Bellechasse was swept up in the whirlwind of events, and after settling at Quebec towards the end of 1836 took an active part in the rebellion of 1837. Morin’s radical stand conformed neither to his temperament nor to his usual conduct. His leadership in the revolt at Quebec was an undeniable failure. Although, according to Antoine Roy, he was “certainly one of the most level headed of those who took up the cause of the rebellion in 1837–1838, . . . he did not have the qualities of a leader. He lacked the energy and decisiveness essential to those who wish a cause that requires the support of the people to succeed.” When a warrant for his arrest was issued, Morin took refuge in the woods of the parish of Saint-François-de-la-Rivière-du-Sud (Saint-François-Montmagny). Arrested on 28 Oct. 1839 he did not remain long in prison, for the accusation of high treason “was so ill founded that it was not considered necessary to undertake to prove it, even before the most accommodating court of the time.”

The hazards of rebellion left Morin penniless, and more and more afflicted with rheumatism. He returned to the practice of law at Quebec, living alone in humble circumstances in a small house on Rue Desjardins. He had developed rather an aversion for politics, but the plan of union quickly revived his interest in public affairs. Under the personal influence of Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine, who visited Quebec in December 1839, Morin was at first inclined to support the union of Upper and Lower Canada since it would foster an alliance with the Upper Canadian Reformers. But he was opposed to the bill as passed in England, since it did not provide for proportional representation in the assembly and granted neither ministerial responsibility nor control of supply. Morin was elected member of the assembly for Nicolet on 8 April 1841, and although he aspired to the office of speaker he yielded to the suggestion of Francis Hincks* that it was better to consolidate the Reform party by supporting Augustin Cuvillier* as candidate.

Morin resigned on 1 Jan. 1842, and on 11 January became a judge for the districts of Kamouraska, Rimouski, and Saint-Thomas. His first term as judge was brief. Sir Charles Bagot* wanted Morin to take the position of clerk of the Executive Council, but he showed little interest in a post which would be “both too near to and too far from the political scene.” He chose instead to become commissioner of crown lands, although this post necessitated procuring a seat in the legislature and giving up the office of judge. Morin was elected representative for Saguenay on 28 Nov. 1842 and resumed his political career.

The commissioner took his new responsibilities seriously. He insisted that his work should be based on personal knowledge. He acquired property and initiated many varied experiments, for example in growing potatoes, stock breeding, crop rotation, maple syrup production, and the experimental cultivation of plants such as grape vines. He made his experiments known to agriculturalists through articles in La Minerve and in specialized American agricultural journals. He also took an interest in the everyday problems of farmers, such as the building and maintenance of roads, the erection of mills, the use of casual farm help, and even the feeding of farmers’ families. To ensure that his experiments would not be ignored, Morin carefully worked out programmes to be used in agricultural schools for farmers’ sons detailing everything from the qualifications of the teaching staff to the syllabus itself. He was not a pure theorist. He assisted in founding new parishes to the north of Montreal: Val-Morin, Sainte-Adèle (from the name of his wife), and Morin-Heights began as a result of his action. His appointment as commissioner of lands had indeed strengthened his interest in agriculture, an interest which continued to grow.

In the general election of 1844 Morin was successful in the counties of Saguenay and Bellechasse. He chose to be member for Bellechasse as much for sentimental reasons as for political security. Although he was no longer one of the executive, Morin was mentioned as the future speaker of the new legislature, but no formal approach was apparently made to him. He devoted his energy to defending the cause of the Catholic clergy in the quarrel over the Jesuit estates, and drafted the School Act of 1845 which established the parish rather than the municipality as the basis of the school system. He also acted as an arbitrator in parochial disputes. His sound judgement and natural level-headedness ensured that in these special legal matters he did not take a radical stand.

In July 1846 the most controversial period of Morin’s political career began. On 31 July he received a letter from William Henry Draper*, which contained an explicit invitation to join the Executive Council. Morin refused the offer on 10 August, affirming his solidarity with the Reform party. The matter seemed closed, but Lord Elgin [Bruce] had not said his last word.

In a final effort to bring Morin and a number of Francophones, including René-Édouard Caron*, into the Executive Council, the governor general sent him a confidential note on 23 Feb. 1847. He expressed again his desire to see Morin join the council. To Morin’s objection concerning his party he replied that he wished “to express his confident hope that objections, founded on personal or party differences (if such exist) will yield to the dictates of Patriotism and public duty.” Morin’s reply was not long in coming. He rejected the new offer but explained his motives more fully. His three years in opposition allowed no room for doubts about his patriotism, but, he clearly stated, he was opposed to the present government. It would be unreasonable in his view not to have a certain measure of unity in the council and his acceptance of a post would not create it. He further declared plainly that his party was ready for a coalition, but not at any price. He concluded by brushing aside the objection that the council lacked Francophone representation confessing he was “convinced that an addition based solely on considerations of origin, and in the circumstances offering all parties concerned only an equivocal position, could not be advantageous to the group for which this arrangement would be made.”

This political document, said to be confidential, did not remain so for long: numerous leaks made it common knowledge. The Reformers were the first to get upset, as the old rivalry between Quebec and Montreal stirred up a lot of malicious gossip. The situation became even more difficult when Le Canadien began on 27 March to publish part of the famous document and garbled quotations from Morin. He was urged to reply to the Quebec paper and its virulent attacks, heavy with implication. Morin refused, for he “had considered that the word confidential imposed on him the obligation to keep private the action he took from the beginning of the negotiations and for several days after.” And his leader Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine declared that he had been perfectly aware of the situation from the outset: “I had to leave Morin free to use his judgement as he thought fit in the interest of the public weal, having always had the greatest confidence in his patriotism, sincerity, and disinterestedness.” The crisis seemed to be resolved by the members’ acceptance of Morin’s interpretation and conduct.

The Reform party was returned to office in the 1847–48 elections, and Morin was elected speaker of the Legislative Assembly over Allan Napier MacNab by an overwhelming majority, obtaining 54 votes against 19 for his opponent, who had held the position since 1844. The newly elected member commanded respect even among his fiercest opponents.

In 1849, during the debate on the Rebellion Losses Bill, Morin displayed remarkable firmness. He had the galleries emptied when uproar persisted, and during the proceedings maintained discipline to an extent he had not shown before [see Bruce]. His imperturbable calm was tested when the parliament buildings in Montreal were set on fire by rioters. The story goes that he even asked for a formal motion of adjournment while the flames were licking the curtains in the hall where the members were sitting! And when the disturbances started again, Morin did not hesitate to have the building in which parliament was meeting guarded by a detachment of soldiers.

In the general election of October 1851 Morin changed counties, abandoning his native constituency of Bellechasse for Terrebonne, where he won easily. Since Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine had given up his position as head of the government, Morin became the colleague of Francis Hincks. But he agreed to be the head of the Lower Canadian section of the government without enthusiasm. He held this post until January 1855, but his profound humility prevented him from being a leader of the stature of La Fontaine.

The legislative activity of the Hincks–Morin government was varied and substantial. Hincks was interested primarily in railways; Morin, as provincial secretary and commissioner of crown lands, was particularly concerned with the abolition of the seigneurial régime, the separate schools of Canada West, and especially the transformation of the Legislative Council into an elective body, a reform he had supported since the 1830s. He was so convinced that an appointed Legislative Council was incompatible with responsible government that in the 1851 election he had announced his intention of resigning if he did not obtain satisfaction on this point. By 24 Sept. 1852 he presented a series of resolutions to make the Legislative Council elective. However, it was not until 1856 that the mlas passed such a bill, and it was accompanied by amendments that limited the effect of Morin’s proposals. By making an elected Legislative Council and abolition of the seigneurial régime part of the Reform programme Morin had removed the most popular weapons from the arsenal of Louis-Joseph Papineau’s Rouges; this action helped to secure the loyalty of the electorate to the Reformers. During these hectic years Morin devoted his leisure to preparing articles for agricultural journals, reading the latest books from France, and checking the standards of the agricultural experiments carried out on his property.

The general elections of 1854 were the first real set-back in Morin’s political career. He was defeated in Terrebonne by a political unknown, Gédéon-Mélasippe Prévost, a “sign of the times,” according to Le Journal de Québec. Bellechasse lost no time in seeking Morin’s candidature, 319 electors from Saint-Michel, Beaumont, and Saint-Vallier signing a petition to that effect. The commissioner of crown lands was ultimately elected unopposed in the united counties of Chicoutimi and Tadoussac. And, from 11 September, Morin and all his colleagues from Canada East agreed to form a team with Allan Napier MacNab.

Ten days after the formation of the new government, Morin was present at the inauguration ceremony of Université Laval; he had had a part in its founding and he was dean of the faculty of law. During the ceremonies he received a doctorate in law, evidence of his fame and his eminence as a jurist.

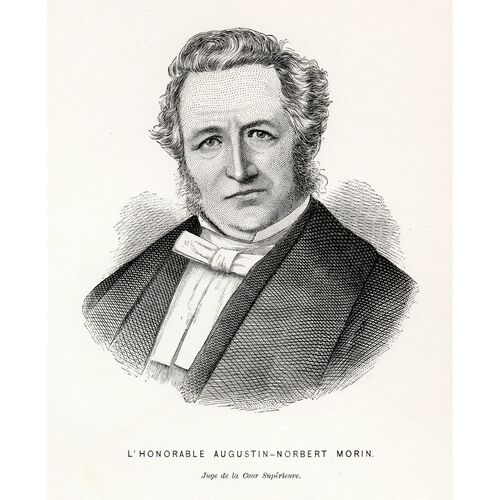

Some months later, in January 1855, Morin resigned from the government because of failing health. He was appointed a judge of the Superior Court, from which he had to take long periods of rest. However, the indefatigable and energetic intellectual managed to found a legal journal, the Law Reporter, with Thomas Kennedy Ramsay*, a Montreal lawyer.

His withdrawal from public activity paved the way for the final work of his life. Because of his competence as a jurist and the quality of his personal judgement, the government asked him to become a member of the commission charged with codifying the civil law of Canada East. Morin consented on 2 Feb. 1858, but he was not officially appointed until 4 Feb. 1859. His colleagues were Charles Dewey Day* and René-Édouard Caron, the latter acting as chairman. Morin attacked this colossal task with uncommon energy. The work books deposited in the Archives du Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe show Morin’s concern for perfection. As the person responsible for civil law, he noted down every possible reference on all pertinent subjects, set out the law as established by judicial decisions based on a library of more than 400 legal works, and drew up a new text. The last report of the commission was submitted in November 1864 to the Legislative Assembly, which studied its seven reports in 1865. Morin was not destined to see the end of his task, for he passed away quietly on 27 July 1865, at Sainte-Adèle de Terrebonne. The new civil code of Canada East, a masterpiece of its kind, came into force on 1 Aug. 1866 [see George-Étienne Cartier*].

Morin was undoubtedly one of the great figures of 19th century Canada. Of indifferent health although unusual stature, he possessed few of the charms that rendered other politicians more attractive to their supporters. Nature had bestowed oratorical talent upon him in miserly fashion, and “art had in no way succeeded in correcting the work of nature.” He was a fervent Patriote, and he had an integrity that was proverbial and undisputed by any adversary. He was a model of the zealous parliamentarian, regular in his attendance in the house, studying all subjects in depth, and assessing the short and long term consequences of every legislative measure. He was alert to developments in his time, neglecting nothing that might improve the economic life of his own people.

Yet “he was too modest and not aggressive enough to become a party leader.” Perhaps also he was too idealistic, too much of a theorist, and too disinterested to feel himself at ease in the game of politics. Although his intelligence and his education set him above the renowned Papineau and La Fontaine, he was not able to command attention, even when he was the head of the Lower Canadian section of the government. His distinction and personal qualities were a drawback politically, and deprived him of a role to which he might have aspired. But no Canadian politician has ever had greater talents for so many diverse disciplines: truly, nothing human was alien to him.

[Documents relating to Augustin-Norbert Morin’s political career are found primarily in PAC, MG 24, which includes the private papers of pre-confederation politicians. Especially useful were the La Fontaine papers (MG 24, B14), the Hincks papers (B68), and the Chauveau papers (B54). The Papineau and Bourassa collections at the ANQ-Q were also consulted. The Duvernay papers at the Château de Ramezay in Montreal (transcript in PAC, MG 24, C3) were helpful for Morin’s activity in journalism. Miscellaneous material on Morin’s studies and his notes in the areas of agriculture and law were consulted at the AAQ, ASQ, and ASSH. j.-m.p.]

L’Avenir, 1848–54. Le Canadien, 1840–55. Le Journal de Québec, 1843–44, 1850–55. La Minerve, 1831–37, 1842–50. Quebec Gazette, 1832–42. Le Jeune, Dictionnaire, II. Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians. Wallace, Macmillan dictionary. Auguste Béchard, L’honorable A.-N. Morin (Québec, 1858). C.-P. Choquette, Histoire du séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe depuis sa fondation jusqu’à nos fours (2v., Montréal, 1911–12), I. André Garon, “La question du Conseil législatif électif sous l’Union des Canadas, 1840–1856” (thèse de des, université Laval, Québec, 1969). Antoine Roy, “Les Patriotes de la région de Québec pendant la rébellion de 1837–1838,” Cahiers des Dix, 24 (1959), 241–54.

Cite This Article

Jean-Marc Paradis, “MORIN, AUGUSTIN-NORBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 3, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morin_augustin_norbert_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morin_augustin_norbert_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean-Marc Paradis |

| Title of Article: | MORIN, AUGUSTIN-NORBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | April 3, 2025 |