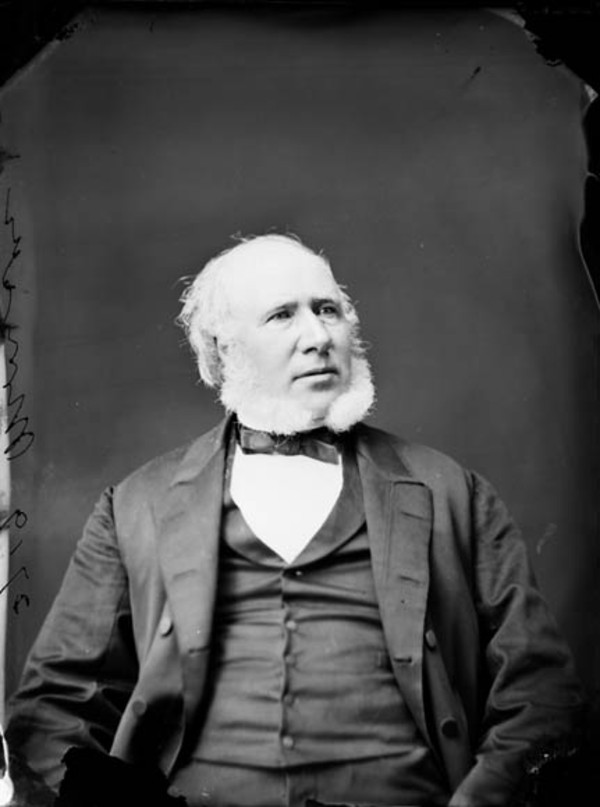

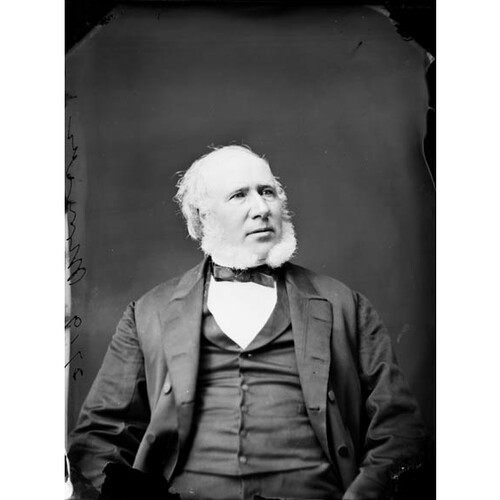

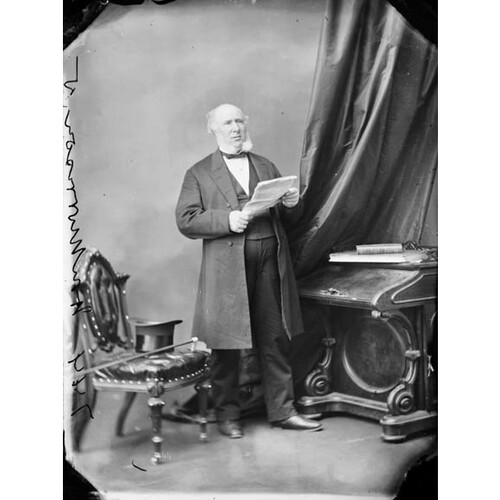

MORRISON, ANGUS, lawyer and politician; b. 20 Jan. 1822 in Edinburgh, Scotland, second son of Hugh Morrison and Mary Curran, and younger brother of Joseph Curran Morrison; m. 5 Aug. 1846 Janet Anne Gilmor, and they had four sons and two daughters; d. 10 June 1882 in Toronto, Ont.

Angus Morrison was brought to Upper Canada by his father, a widower and a discharged sergeant in the 42nd Foot (Royal Highland Regiment). Hugh Morrison settled in Georgina Township in June 1830 with the apparent intention of farming. By January 1831 he had married Frances (Fanny), sister of John Montgomery*, moved to York (Toronto), and opened the Golden Ball Tavern. There is no record of Angus having attended Upper Canada College as is often reported; more likely, he attended a grammar school in Toronto, though after the death of his father in August 1834 and a rift in the family over the estate, he may have received much of his education from his brother. In 1839, when Joseph opened a law office with William Hume Blake*, Angus joined the firm as clerk. Called to the bar in 1845, the younger Morrison established his own practice on King Street, the financial and commercial heart of the city.

Morrison was an extremely popular and well-known young man in the city. Broad-chested, of average height, with thick curly hair and stylish mutton chop sideburns, he was considered a gentleman of fashion. Much of his public reputation, however, was based on his athletic achievements. He competed in the annual sculling races on Lake Ontario, being declared “Champion of Toronto Bay” in 1840 and 1841, and as an avid curler he took part in many of the all-day matches held on the bay. Morrison helped organize the Toronto Curling Club and the Toronto Rowing Club, serving as president of the latter for many years. Consistent with his Scottish background, he was also active in the St Andrew’s Society. Predictably, Morrison parlayed his family relations, social connections, and public image into a substantial legal practice based on corporate affiliations rather than court appearances. He acted as solicitor for many institutions, including the Ontario Building Society, the University of Toronto, and, after it opened in 1867, the Canadian Bank of Commerce. Morrison’s popularity also undoubtedly assisted his election as alderman for St James’ Ward in 1853 and 1854.

In the summer of 1854, following the collapse of the ministry of Francis Hincks and Augustin-Norbert Morin*, Morrison was chosen the Reform candidate for the newly created riding of Simcoe North at a convention held at Barrie. Winning the election in July, he soon proved a capable politician. Although Toronto-based, he maintained a high public profile in his riding and supported popular local issues. Perhaps more important, Morrison shrewdly played a strategic role in the distribution of local patronage whenever the opportunity arose.

Morrison’s popularity in Simcoe North was, however, based on his involvement in, and promotion of, transportation schemes. In these years when both metropolis and hinterland eagerly supported the development of transportation networks, Morrison, as a representative of both Toronto and Simcoe North interests, quite naturally gained much support by encouraging railways, canals, navigation companies, and, of particular interest to his constituents, colonization roads. Not surprisingly, he was returned by acclamation in 1857. In the election of 1861, however, because the transportation developments had not paid the expected dividends, Morrison was forced into a vigorous campaign, and barely managed to retain his seat. By 1863 matters were worse; some of the developments, such as the Northern Railway, of which he had been a director, were deeply in debt, causing financial difficulties for the Simcoe County Council and providing ammunition for his opponents. The election, which Morrison lost, was a riotous one in which it was reported that “Whiskey was sent into the Townships in streams.”

A coalition Reformer, Morrison was recruited by the Conservatives in Niagara for a by-election in September 1864; he won by a slim majority. In the elections of 1867, although unsuccessful in the provincial riding of Simcoe North, he retained Niagara in the federal parliament for the Conservatives and was re-elected in 1872. In the House of Commons he continued to be involved in transportation schemes and, presumably because of his experience, acted as one of the party whips. In 1874 Morrison took on the difficult task of trying to win the federal riding of Toronto Centre from the Liberal, Robert Wilkes*. He was unsuccessful, and although Wilkes’s election was overturned a few months later, Morrison declined to run again.

In December 1874 Morrison allowed his name to be placed on the mayoralty ballot in Toronto, along with Francis Henry Medcalf* and Andrew Taylor McCord, but withdrew from the contest before the poll. The following December, however, he actively pursued the nomination for mayor and after a strong campaign easily defeated the incumbent, Medcalf. The Globe reported that Morrison’s “personal popularity” was the key to his victory; indeed, he lost only one of the nine wards, polling 4,425 votes to Medcalf’s 2,673.

As mayor, Morrison characteristically maintained a high public profile. In 1876 he represented Toronto at the Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition, where he purchased the prize-winning fountain and donated it to the citizens of Toronto; at the same exhibition, he watched Edward (Ned) Hanlan* win the sculling race and presented him with a gold watch. Easily re-elected in 1877 and 1878, Morrison proved to be a capable administrator. He oversaw a reorganization of the standing committees which included the creation of the executive committee. He also completed a long-overdue restructuring of the Water Works Commission, and in 1878 he concluded negotiations with the federal government which allowed the city to take over the exhibition grounds.

As was the case during his first experience on city council in the 1850s, Morrison again found that railways were an important issue for Toronto. Attempting to avoid the financial calamities of earlier promotions, and considering the depressed nature of the economy, men such as George Laidlaw were promoting the construction of narrow gauge feeder lines. The Toronto City Council had supported these schemes, and between 1868 and 1876 had awarded $710,000 in bonuses to several projects, including $100,000 in 1873 to Laidlaw’s Credit Valley Railway. By the beginning of Morrison’s first term many lines were in financial difficulty, especially the Credit Valley. Laidlaw, unable to attract private capital, was energetically pursuing funds at all levels of government. As a director, shareholder, and solicitor of the Credit Valley, Morrison had been regarded by the promoters of the railway as a good choice for mayor, though some had expressed concern that he lacked the “vim” to push a second bonus through the council. Nevertheless, only a few weeks after Morrison’s election in 1875, the city council received the required petitions asking for the granting of a bonus of $250,000. The issue was delayed pending a report by the city engineer, Francis Shanly, and it was not until 7 March 1877, at a boisterous council meeting, replete with resignations of aldermen, that the by-law effecting a bonus was passed. According to provincial statute, by-laws for bonuses required the approval of the ratepayers and Morrison chaired a public meeting to promote the acceptance of this by-law. When the vote was taken on 3 April, it was approved.

Although nominated for a fourth term in December 1878, Morrison declined to stand, and after a halfhearted bid for the mayoralty in 1880 retired from public life. His law firm, by this time styled Morrison, Sampson and Gordon, had flourished and undoubtedly provided him with a more than adequate income. He had been made a qc in 1873. His death, on the night of 10 June 1882, was a shock to the entire community and his funeral, a municipal event, was reported to have consisted of more than 90 carriages.

AO, MU 472, Thomas McCraken to Alexander Campbell, 26 Oct. 1876; MU 508, Alexander Campbell to R. J. Cartwright, 28 June 1873; MU 1376, J. A. Macdonald to Egerton Ryerson, 7 Feb. 1862; RG 1, C-IV, Georgina Township papers, Concession 7, Lot 3; RG 22, ser.6-2, York County, Will of Hugh Morrison, 11 June 1833; RG 49, I-7-B-3, box 8, Credit Valley Railway file. CTA, Angus Morrison information file; RG 1, A1, 1876; 12 June 1882; RG 2, B1, 1876; 1877; RG 5, H1. PAC, MG 24, B40, 5: 237–38. Canadian North-West (Oliver), II: 875. Macdonald, Letters (J. K. Johnson and Stelmack), II: 160, 247. Canadian Freeman (Toronto), 15 June 1863; 8 Sept. 1864; 22, 29 Aug., 19 Sept. 1867. Colonial Advocate (Toronto), 12 Aug. 1834. Examiner (Toronto), 11 March 1840. Globe, December 1874, January 1876. Northern Advance and County of Simcoe General Advertiser (Barrie, [Ont.]), 12, 19, 26 July 1854; 5 Feb. 1857; 12 June 1861; 3, 24 June 1863; 8 Aug. 1867. Canadian biog. dict., I: 419–20. Dominion annual register, 1882: 352. Toronto directory, 1833–34; 1846–47; 1850; 1856; 1871–80. A. F. Hunter, A history of Simcoe County (2v., Barrie, 1909; repr. 1948). Angus MacMurchy, Sketch of the life and times of Joseph Curran Morrison and Angus Morrison . . . (n.p., [1918]). V. Ross and Trigge, Hist. of Canadian Bank of Commerce, II: 10. D. G. G. Kerr, “The 1867 elections in Ontario: the rules of the game,” CHR, 51 (1970): 369–85.

Cite This Article

Victor Loring Russell, “MORRISON, ANGUS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morrison_angus_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morrison_angus_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Victor Loring Russell |

| Title of Article: | MORRISON, ANGUS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |