GIROUARD, JEAN-JOSEPH, militia officer, notary, politician, Patriote, portrait painter, and philanthropist; b. 13 Nov. 1794 at Quebec, son of Joseph Girouard and Marie-Anne Baillairgé; d. 18 Sept. 1855 in Saint-Benoît (Mirabel), Lower Canada.

Jean-Joseph Girouard’s forebear, François Girouard, came to live in Acadia during the 1640s. Following the deportation, a small number of his descendants, including Jean-Joseph’s grandfather, Joseph Girouard, went to Quebec, settling there during the Seven Years’ War. In his youth Jean-Joseph’s father was apprenticed to Jean Baillairgé*, a master carpenter. He worked subsequently as a shipbuilding contractor at Quebec. There he married Baillairgé’s youngest daughter, Marie-Anne, in 1793, and they had three children: Jean-Joseph, Angèle, and Félicité. From his paternal ancestors Jean-Joseph retained an instinctive and lasting distrust of England. From his mother he inherited the artistic tradition of the Baillairgé family.

In September 1800, at the age of five, Jean-Joseph lost his father, who was drowned while sailing off Wolfe’s Cove (Anse au Foulon). After Joseph’s death the boy, his mother, and his two sisters were given shelter in his maternal grandfather’s house, where he remained from the age of six until he was ten. It was during this period that the young boy learned something of the skills of the Baillairgé family, whose name was already well known at Quebec. In the diary that he kept later with his second wife, he described how he learned from his grandfather “the rules of finding cubic content.” He also recalled seeing his uncles François* and Pierre-Florent* busy at their saw-horses while he tried his own hand, almost in fun, at the various tasks undertaken in the Baillairgé workshop.

After her father’s death in 1805 Mme Girouard met Jean-Baptiste Gatien, one of his close friends, who was priest of the parish of Sainte-Famille on the Île d’Orléans. Gatien proposed that she become the housekeeper in his presbytery and bring her children to Sainte-Famine. She agreed, and Gatien looked after their material needs; he also assumed responsibility for the children’s intellectual and religious instruction. He could find no praise great enough for his young pupil Jean-Joseph, whom he thought exceptionally talented. None of the subjects he studied – music, painting, architecture, physics, or mathematics – gave any trouble to Jean-Joseph’s gifted mind. The boy was also well behaved, thoughtful, and reflective, as the portrait painted by François Baillairgé suggests.

Mme Girouard and her children followed Gatien when he was sent to take charge of the parish of Sainte-Anne at Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines in 1806, and again in 1811 when he became priest at Saint-Eustache. Having assimilated the general knowledge imparted by his tutor, in 1811 Girouard began training as a notarial clerk under Joseph Maillou at Sainte-Geneviève (Sainte-Geneviève and Pierrefonds), on Montreal Island. At the beginning of the War of 1812 he was too young to be called up for militia service but became a volunteer in a corps at Lachine. When Maillou was called to the colours, Girouard left the corps and continued his training under Pierre-Rémi Gagné at Saint-Eustache. In November 1812, having reached enlistment age, he served at Montreal as an adjutant in the Lavaltrie Battalion of militia under Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph-Édouard Faribault. After his return to Saint-Eustache at the end of the war he finished his clerkship and took his examinations. On 13 June 1816 he received his commission as a notary, and that year settled in Saint-Benoît, a village adjoining Saint-Eustache, where he spent the rest of his life.

That a man such as Girouard was to become a rebel can be explained only by the environment in which he lived. Girouard opened an office in the house of Jean-Baptiste Dumouchel*, a merchant in the village with whom he soon became friends. On 24 Nov. 1818 he took as his first wife Dumouchel’s sister-in-law Marie-Louise Félix, whose brother Maurice-Joseph was the priest of the parish of Saint-Benoît. Through his marriage the young notary quickly secured entry to the small circle of village society and sealed his friendship with Dumouchel by family ties. From then on, enjoying the high regard of the townspeople and possessing undeniable talents as a notary, Girouard attracted numerous clients, the most regular being Dumouchel, and eventually acquired a sound reputation in his profession.

In the autumn of 1821 Governor Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*] appointed Girouard a captain in the Rivière-du-Chêne battalion of militia, a position he retained until the beginning of 1828. On 7 March 1827 Dalhousie decided to adjourn the House of Assembly because of the conflict which had developed between it and the Legislative Council. During the electoral campaign the following summer, Girouard travelled through York riding with the Patriote party candidate, Jacques Labrie*, and Jean-Olivier Chénier*. In July several Patriote supporters, in particular Dumouchel, Joseph-Amable Berthelot, and Labrie, all three close friends of Girouard, were dismissed as militia officers because they had taken part in election meetings. As a token of protest against these unjust dismissals, Girouard resolutely returned his commission as a militia captain to the governor in January 1828. Meanwhile, Girouard and Chénier had none the less succeeded in getting Labrie elected, in a climate of violence heralding the stormy years before the rebellion.

Following Labrie’s death in 1831 Girouard was chosen by acclamation as member in the assembly for the new constituency of Deux-Montagnes, which had been part of York riding. He set to work soon after arriving at Quebec in January 1832 and became a keen supporter of Louis-Joseph Papineau* and a close friend of Augustin-Norbert Morin*. He had not been blessed with oratorical gifts, however, and rarely contributed to the fiery debates in the assembly. He preferred to sit on committees studying matters such as municipal affairs, regulations governing the notarial profession, and education. In 1834 he supported unreservedly the 92 Resolutions, which outlined the principal grievances and demands of the assembly.

General elections had been planned for the autumn of that year, and it was anticipated that the struggle would be extremely fierce. In these circumstances Girouard, who had a gentle and timid disposition, was reluctant to rush into the political arena, but he finally agreed to run as a Patriote party candidate along with William Henry Scott, the other member for Deux-Montagnes. The English party decided to contest the seat, James Brown* and his brother-in-law Frédéric-Eugène Globensky campaigning as candidates. The electoral struggle, as foreseen, gave rise to violence: in riots at St Andrews (Saint-André-Est) numerous people were hurt, including Scott and Dumouchel, and a veritable street battle developed at Saint-Eustache. As a result of the incidents at Saint-Eustache, Stephen Mackay, the returning officer who was also a brother-in-law of Globensky, quickly stopped the voting, in order, he said, to put an end to the violence constantly erupting around the polling-booth. Fearing that the English party candidates would be defeated, he resorted to a subterfuge. He declared Girouard and Scott elected, although they had 30 votes fewer than Brown and Globensky, the hope being that the English party could contest the election results. However, Girouard and Scott resumed their seats in the assembly and kept them until 1837; no one ever ventured to raise an objection.

On the eve of the outbreak of the rebellion in November 1837, Girouard, who had taken an active part in Patriote meetings at Saint-Benoît and the neighbouring villages during the preceding three years, was regarded by the authorities as a leader of the resistance movement in the Lac des Deux-Montagnes region, along with Chénier and Luc-Hyacinthe Masson*. His name was on the list of outlaws, beside the names of Papineau and Morin. There was a price on his head and a reward of £500 for anyone who turned him in. On 13 December Sir John Colborne* and his troops left Montreal and headed for Saint-Eustache and Saint-Benoît, to arrest in particular Chénier, Amury Girod*, Dumouchel, and Damien and Luc-Hyacinthe Masson, as well as Girouard. At Saint-Eustache, Chénier and his supporters decided to go down fighting. At Saint-Benoît, on the other hand, Girouard persuaded the villagers to lay down their arms and surrender, while the outlawed leaders sought refuge in flight. He himself made his way to Rigaud, where he found shelter with a habitant. Meanwhile Colborne and his troops, along with the volunteers from neighbouring villages, sacked and set fire to Saint-Benoît. Girouard hid for some days at Coteau-du-Lac, but soon learned in his hide-out that his supporters had been arrested and put in jail at Montreal. Rather than pursuing his plan to reach the American border, he decided to give himself up to Colonel John Simpson*, who was stationed at Coteau-du-Lac, and to place his legal knowledge at the disposal of his friends who were accused of high treason.

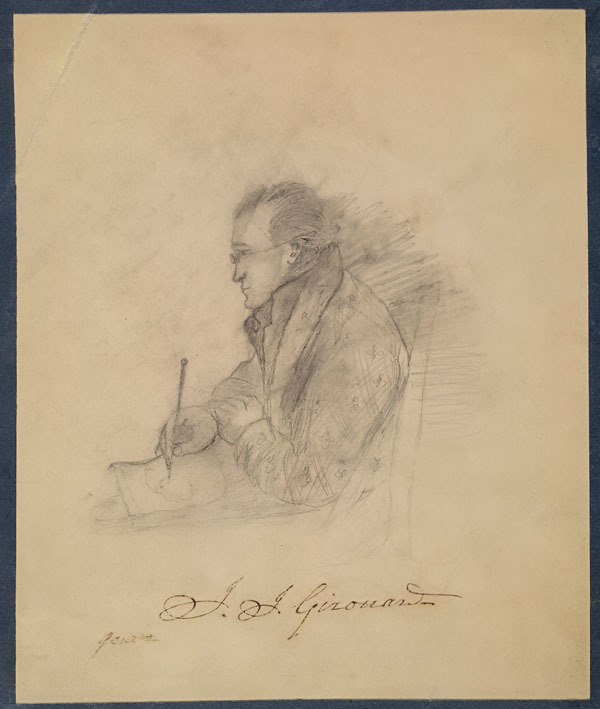

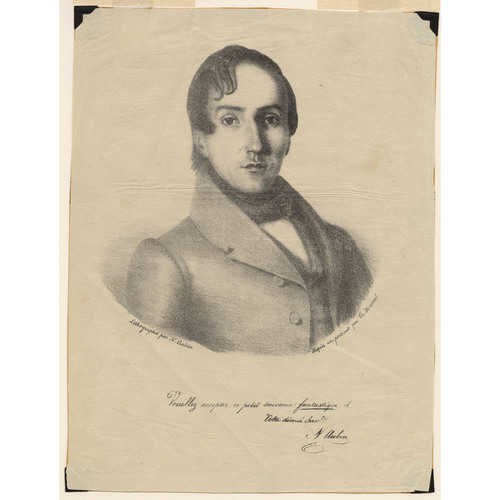

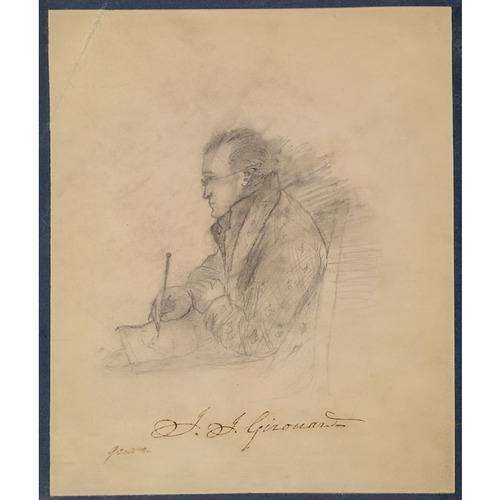

Girouard was taken to Montreal and imprisoned on 26 Dec. 1837. He continued to be active behind bars. He managed to acquire a small table for a desk, and Adèle Berthelot, the wife of Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine*, got pencils and drawing paper for him. There he maintained a notarial “office” and a painter’s studio. Friends came to ask him to paint their portraits and he executed these with the skill of a master. He frequently gave advice and wrote letters, including personal letters to the families of those in custody in which he often included a portrait of the prisoner.

Girouard was quickly reassured as to the prisoners’ lot. After initially harsh treatment, discipline within the jail became much less severe. He was no longer worried about his fate or that of his friends. He kept up correspondence with La Fontaine, who had reached England and who sent encouraging news to the French Canadian Patriotes. Moreover, Girouard’s temperament led him always to attribute kind intentions not only to his friends but even to his enemies. He radiated serenity, a serenity which spread to the other prisoners.

With the arrival of Lord Durham [Lambton*] in May 1838, a general amnesty was expected. Before settling the fate of the prisoners, however, Durham sent Simpson to the jail in Montreal to extract confessions from the chief prisoners. Girouard objected to this procedure and refused to sign any document containing an admission of guilt. In addition he used his influence to dissuade his companions from agreeing to any statement, however honourable in appearance, attesting to their responsibility in the revolutionary movement. Despite Girouard’s advice, eight prisoners signed a confession of guilt and were condemned to be deported to Bermuda. Girouard was released on 16 July, only a few days after Lord Durham’s amnesty, on bail of £5,000. He was imprisoned again at Montreal following the second uprising, because of his past record, and released on 27 December. When he recovered his freedom, Girouard had nothing left: his large house had been burned down, as had another dwelling he owned in the village of Saint-Benoît; his notarial minute-book, his books, and his physics and astronomical instruments had been either looted or burned. His wife had not been harmed, thanks to the charity of her brother-in-law Ignace Dumouchel of Rigaud. Girouard was no longer young. At 44 he could count only on relatively good health and his great personal and professional qualities.

Profoundly embittered by the British army’s attitude at the time of the sacking of Saint-Benoît, and disappointed with his fellow man and with political action, Girouard went back to his village, where he decided to devote himself to his profession as a notary and to the study of science and philosophy. When a group of political leaders of the Province of Canada, notably Simpson, René-Joseph Kimber, Frédéric-Auguste Quesnel*, Joseph-Édouard Turcotte*, Louis-Michel Viger, Étienne Parent*, and Étienne-Paschal Taché*, literally besieged his Saint-Benoît retreat to persuade him to participate in the new ministry proposed by Governor Sir Charles Bagot* in September 1842, they met with a polite but dignified and emphatic refusal. At the risk of offending La Fontaine, the former member for Deux-Montagnes sent the governor a letter of refusal in which he pleaded reasons of health for declining. Girouard was not ill, but he took refuge behind a lofty and contemptuous attitude betraying his scorn for the idea of collaborating with those whom he considered of little faith and integrity. He continued to lead an active professional life centred on his office. Moreover, he was often called to Montreal, Rigaud, and the parishes south of Montreal to deal with estate matters, in which he had become highly skilled. It was he who settled the difficult estates of seigneurs Joseph Masson* of Terrebonne and Charles de Saint-Ours*.

On 2 April 1847 Girouard lost his wife; they had had no children. On 30 April 1851 he took as his second wife Émélie Berthelot, the daughter of his longstanding friend Joseph-Amable Berthelot, a notary of Saint-Eustache. They had two daughters, one of whom died at birth, and two sons. Émélie Girouard had always dreamed of becoming the founder of an almshouse. She realized this dream with the help of her husband, who fully shared her enthusiasm for the project. In one of her three diaries, Mme Girouard devoted many pages to describing the ups and downs that she and her husband experienced in building the Hospice Youville in Saint-Benoît. Girouard allocated all the income from the indemnity he had received in January 1853 for his losses during the rebellion, £924 (he had claimed £2,424 7s.), to the construction of a convent for the education of girls and the care of the elderly. In addition to endowing this establishment, he and his wife personally shared in the work, carrying out as many tasks as they could. Girouard, the grandson of Jean Baillairgé, designed the hospice and the decoration of the chapel himself. He donated the land for the building, hired the contractors, and with his wife’s help supervised the construction work.

Girouard and Émélie truly put their hearts and souls into the building of the Hospice Youville, which they considered the crowning achievement of their lives. When Bishop Joseph La Rocque*, the administrator of the diocese of Montreal in the absence of Bishop Ignace Bourget*, came on 9 Nov. 1854 to preside at the opening of this convent, which was committed to the care of the Sisters of Charity of the Hôpital Général in Montreal, it was indeed a supreme moment for the couple. For Mme Girouard this event seemed a mystic consecration of her union with her husband. The building still stands; instruction is no longer given to young girls, but it does provides a home for the elderly.

Girouard died, most likely of pulmonary tuberculosis, on 18 Sept. 1855 in Saint-Benoît, at the age of 60. He was buried three days later in the chapel of the hospice he had founded. He might be judged to have had a narrow existence because he confined his talents to his family and his parish, when everything destined him for a brilliant political career. In public life he never had any title higher than that of member for his riding in the House of Assemblet this likeable figure deserves a place in the historical record for several reasons, as notary and Patriote, as portrait painter and artist, and as the philanthropist who endowed his parish with a home for the elderly. From all these points of view Girouard is memorable. But he himself would have liked his name to be remembered especially for his charitable works. After his death, to honour his memory, the habitants in the Lac des Deux-Montagnes region called Girouard “the father of the poor.”

Jean-Joseph Girouard’s minute-book was destroyed by fire during the sack of Saint-Benoît in December 1837, and only part of its index has been preserved. This document, which lists the titles of 4,025 instruments notarized by Girouard from 27 June 1816 to December 1830, is held at the ANQ-M, CN1-179.

Girouard is the author of Relation historique des événements de l’élection du comté du lac des Deux Montagnes en 1834; épisode propre à faire connaître l’esprit public dans le Bas-Canada (Montréal, 1835; réimpr., Québec, 1968). He is also the co-author, along with his second wife, of the “Journal de famille de J.-J. Girouard et d’Émélie Berthelot,” composed between 1853 and 1896. This 193-page journal is full of minor incidents in the life of the Girouard family. The first 23 pages are in Girouard’s hand. The second part of the journal, pages 23 to 193, is entirely the work of Émélie Berthelot, who after the death of her husband in 1855 continued the account of family events. This document forms part of the Coll. Girouard in ANQ-Q, P–92.

Girouard drew a portrait of the Patriotes who were held in the Montreal jail on charges of high treason at the end of 1837 and the beginning of 1838. In 1846 he also presented a carefully detailed inventory of the losses he had suffered in the looting of Saint-Benoît to the Rebellion Losses Committee, established to compensate the victims of 1837. These documents were published by Paul-André Linteau in “Documents inédits,” RHAF, 21 (1967–68): 281–311, 474–83.

Girouard also sketched a great many portraits, especially during the period when he was a member of the House of Assembly of Lower Canada, and while he was behind bars in the Montreal jail. A collection of 102 of these pencil sketches is now in the possession of his great-grandson, Pierre Décarie, of Dorval, Que., and consists for the most part of portraits of Patriotes imprisoned in 1837–38 and of several members of the Baillairgé family. Girouard’s artistic works also include a view of the ruins of Saint-Benoît, a plan of the Montreal jail, a self-portrait, a magnificent portrait of Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine, and the plans for the Hospice Youville in Saint-Benoît.

ANQ-M, CE6-9, 24 nov. 1818, 21 sept. 1855; CE6-11, 30 avril 1851; CN6-15, 29 avril 1851. ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 5 févr. 1793, 14 nov. 1794; E17/12–14, nos.646–840; P-52/13. Arch. de l’Institut d’hist. de l’Amérique française (Montréal), Coll. Girouard. Arch. des Sœurs Grises (Montréal), Dossier Saint-Benoît, historique. PAC, MG 11, [CO 42] Q, 239: 373; 259-2: 265–66; MG 24, A27, 34; A40, 27; B2, 32; B4, 8: 525; RG 4, B8, 4: 1386–88; B20, 32. R.-S.-M. Bouchette, Mémoires de Robert-S.-M. Bouchette, 1805–1840 (Montréal, 1903). Alfred Dumouchel, “Notes d’Alfred Dumouchel sur la rébellion de 1837–38 à Saint-Benoît,” BRH, 35 (1929): 31–51. Placide Gaudet, “Généalogie des Acadiens, avec documents,” PAC Rapport, 1905, 2, iiie part.: 60. Amury Girod, “Journal tenu par feu Amury Girod et traduit de l’allemand et de l’italien,” PAC Rapport, 1923: 408–19. “Lettre de M. Girouard à M. Morin, sur les troubles de 37 dans le comté des Deux Montagnes,” L’Opinion publique, 2 août 1877: 361–62. Rapports des commissaires sur les pertes de la rébellion des années 1837–1838 (s.l., [1852]). L’Aurore des Canadas (Montréal), 28 août 1841. Le Canadien, 1831–37. La Gazette de Québec, 1821–38. La Minerve, 1827–37; 29 déc. 1855. F.-J. Audet, “Les législateurs du Bas-Canada.” F.-M. Bibaud, Le panthéon canadien (A. et V. Bibaud; 1891). Desjardins, Guide parl. Fauteux, Patriotes, 253–56. Quebec almanac, 1822–27. P.-G. Roy, Fils de Québec, 3: 71–73. G.-F. Baillairgé, Notices biographiques et généalogiques, famille Baillairgé . . . (11 fascicules, Joliette, Qué., 1891–94), 1–2; 6. Auguste Béchard, Galerie nationale: l’honorable A.-N. Morin (2e éd., Québec, 1885). L.-N. Carrier, Les événements de 1837–38 (2e éd., Beauceville, Qué., 1914). Béatrice Chassé, “Le notaire Girouard, Patriote et rebelle” (thèse de d ès l, univ. Laval, Québec, 1974). Christie, Hist. of L.C. (1866). David, Patriotes, 53–64, 79–90. Émile Dubois, Le feu de la Rivière-du-Chêne; étude historique sur le mouvement insurrectionnel de 1837 au nord de Montréal (Saint-Jérôme, Qué., 1937), 61–62, 66, 118–19. [Albina Fauteux et Clémentine Drouin], L’Hôpital Général des Sœurs de la charité (Sœurs grises) depuis sa fondation jusqu’à nos jours (3v. parus, Montréal, 1916– ), 3: 25–34. Filteau, Hist. des Patriotes (1975). Désiré Girouard, La famille Girouard en France (Lévis, Qué., 1902). [C.-A.-M. Globensky], La rébellion de 1837 à Saint-Eustache avec un exposé préliminaire de la situation politique du Bas-Canada depuis la cession (Québec, 1883; réimpr., Montréal, 1974). A.[-H.] Gosselin, Un bon Patriote d’autrefois, le docteur Labrie (2e éd., Québec, 1907). Laurin, Girouard & les Patriotes, 5–20. Meilleur, Mémorial de l’éducation (1876), 295. Monet, Last cannon shot. P.-G. Roy, La famille Berthelot d’Artigny (Lévis, 1935). R.-L. Séguin, Le mouvement insurrectionnel dans la presqu’île de Vaudreuil, 1837–1838 (Montréal, 1955). Taft Manning, Revolt of French Canada. André Vachon, Histoire du notariat canadien, 1621–1960 (Québec, 1962). F.-J. Audet, “Les députés de la vallée de l’Ottawa, John Simpson (1788–1873),” CHA Report, 1936: 32–39. L.-O. David, “Les hommes de 37–38: Jean-Joseph Girouard,” L’Opinion publique, 19 juill. 1877: 337–38. Bernard Dufebvre [Émile Castonguay], “Une drôle d’élection en 1834,” Rev. de l’univ. Laval (Québec), 7 (1952–53): 598–607. [Désiré Girouard], “La famille Girouard,” BRH, 5 (1899): 205–6. Léon Ledieu, “Entre nous,” Le Monde illustré (Montréal), 5 nov. 1887: 210–11. “Quelques Girouard,” BRH, 47 (1941): 350–51. [Arthur Sauvé], “Évocation d’un passé plein de gloire: les trois Girouard,” Le Journal (Montréal), 10 févr. 1900: 5.

Cite This Article

Béatrice Chassé, “GIROUARD, JEAN-JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/girouard_jean_joseph_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/girouard_jean_joseph_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Béatrice Chassé |

| Title of Article: | GIROUARD, JEAN-JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |