Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

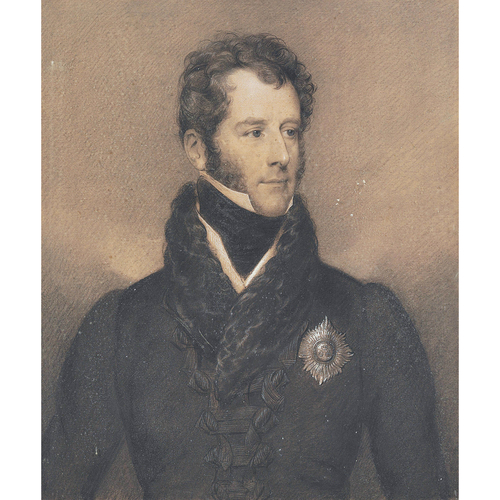

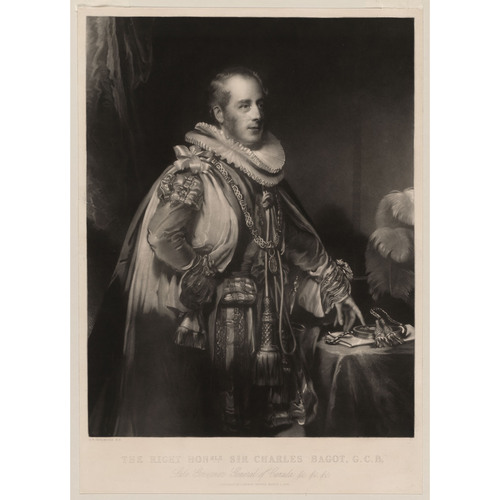

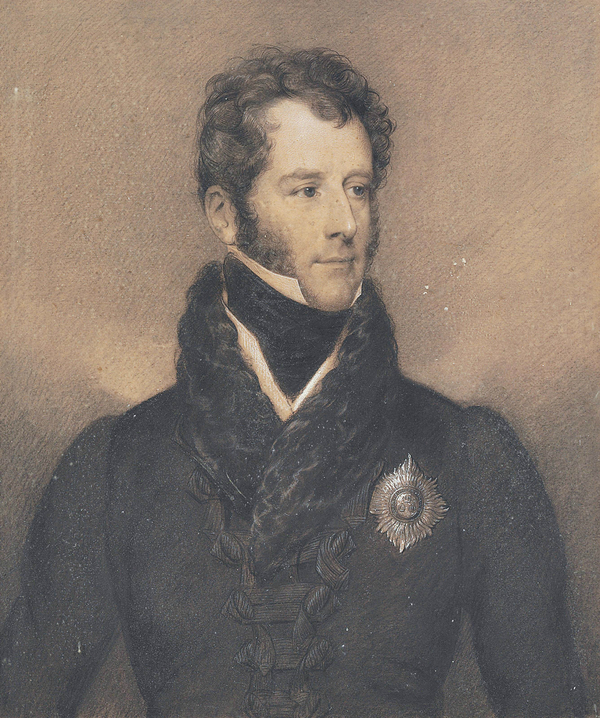

BAGOT, Sir CHARLES, colonial administrator; b. 23 Sept. 1781 at Blithfield Hall, England, second surviving son of William Bagot, 1st Baron Bagot, and Elizabeth Louisa St John, eldest daughter of John St John, 2nd Viscount St John; d. 19 May 1843 in Kingston, Upper Canada.

Charles Bagot was descended from aristocratic English families which traced their lineages to the Norman conquest. His education, at Rugby School and Christ Church College, Oxford, befitted his social position. In 1801 he was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn but, disliking law, he abandoned his studies within a year. He returned to Oxford and obtained an ma in 1804. On 22 July 1806 he married Mary Charlotte Anne Wellesley-Pole, whose father, William Wellesley-Pole, later succeeded to the earldom of Mornington and whose uncle Arthur Wellesley became Duke of Wellington. Bagot and his wife were to have four sons and six daughters.

In 1807 Bagot took a seat in parliament as the member for Castle Rising, a rotten borough controlled by his uncle Richard Howard. A follower of the foreign secretary, George Canning, Bagot became under-secretary for foreign affairs in August 1807. At the end of his mentor’s term of office in 1809 he found himself without a post. He also no longer held his parliamentary seat, for in 1807 he had accepted the stewardship of the Chiltern Hundreds, a legal figment which permitted him to resign from the Commons in order to assume a government office. His association with Canning, however, had developed into a close friendship which, along with his extensive family connections, would launch him on a distinguished diplomatic career.

Bagot was named minister plenipotentiary to France on 11 July 1814, but the appointment was temporary; he was replaced by Wellington later that summer. His diplomatic career began in earnest on 31 July 1815 when he was appointed minister plenipotentiary and envoy extraordinary to the United States. It was a difficult assignment, for the Americans kept grudging memories of the War of 1812, and the issues arising out of the hostilities were complicated. Although Bagot was only 34 and had little diplomatic experience, he handled the assignment with tact and sensitivity, won the respect and friendship of the American administration, and became well liked in the American capital.

He also proved to be an astute negotiator, and left his name to the Rush–Bagot agreement concerning the reduction of naval forces on the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain. Worked out during 1816 with the American secretary of state, James Monroe, the agreement was formalized by an exchange of diplomatic notes on 28 and 29 April 1817 between Bagot and the new secretary of state, Richard Rush, and was later ratified by the American Senate. It limited naval armament on the lakes to vessels of 100 tons maximum, with each side being permitted only one such vessel on lakes Champlain and Ontario and no more than two vessels on the remaining lakes. Bagot was also involved in negotiations with the American government to settle a number of other disputes concerning fisheries and the border from Lake of the Woods to the Pacific. The issues were finally resolved in London by the Convention of 1818. He returned to England the following year and, in anticipation of the coronation of King George IV, he was created a gcb on 20 May 1820. Bagot’s role in the settlement of boundary issues concerning British North America did not end with his assignment in Washington. As ambassador to Russia from 1820 to 1824 he took part in the negotiations leading to the Anglo-Russian treaty of 1825 which fixed the boundaries of what is now Alaska for the next 75 years.

In the fall of 1824 Bagot was sent as ambassador to The Hague, where King Willem I of the Netherlands was attempting unsuccessfully to unify Holland and Belgium in law, language, and religion. There he became familiar with the problems posed by cultural duality within a single state and took part in the negotiations which ultimately established the independence of Belgium in 1831.

It was a measure of Bagot’s high reputation that he was offered the governor generalship of India in 1828. He declined, and after his departure from The Hague in 1831 took part in only one brief mission over the next ten years, to Vienna in 1835. When Sir Robert Peel returned to office as prime minister in September 1841, Bagot agreed to succeed Lord Sydenham [Thomson] as governor-in-chief of the recently united Province of Canada at a time when that province was undergoing a political crisis. His appointment made sense, despite his lack of parliamentary experience, for he had the personality and sound judgement required for colonial politics. Also, his knowledge of the United States was critical given that belligerent expansionism once more inflamed American politics and threatened to disrupt Anglo-American relations. Indeed, as Peel explained in reply to Charles Buller’s letter concerning the selection of a suitable candidate, “the knowledge that [Bagot] was one of the most popular ambassadors ever accredited to the United States” played an important role in his nomination. Bagot was appointed on 27 Sept. 1841 and arrived in the Canadian capital, Kingston, on 10 Jan. 1842, taking office two days later.

In the wake of the rebellions of 1837–38 the Colonial Office had decided on a policy of harmony between the executive and the legislative branches of the government which was designed to accommodate the House of Assembly but not to submit to the demands of reformers for responsible government. This policy was proving increasingly difficult to administer, for cooperation between the French- and English-speaking reformers in the province created a formidable alliance of opposition members. Sydenham had pulled together an Executive Council and maintained harmony with the assembly by offering inducements that transcended party lines, but as his promises ran out, underlying partisan alignments had begun to re-emerge.

In keeping with the strategy of assimilation proposed by Lord Durham [Lambton], Sydenham had taken steps to make Lower Canada essentially British. Although Bagot was to maintain this strategy, he was also instructed by the Colonial Office to try to win the Canadians’ acceptance of the union of the Canadas. As a new governor, Bagot was wise enough to rely on advisers who were more familiar with the colony. Among them were Thomas William Clinton Murdoch, the civil secretary he inherited from his predecessor, who offered an expert assessment of the claims and aspirations of the Canadians, and Sir Richard Downes Jackson, who had served as administrator since Sydenham’s death and had begun a strategic distribution of government offices among Canadians as a means of winning their acceptance of the union. Bagot carried on Jackson’s strategy by appointing prominent Canadians to a number of positions in the government and the judiciary; the appointees included a French-speaking Catholic deputy superintendent of education for Lower Canada, Jean-Baptiste Meilleur*. He also suspended proclamation of a decree that the Special Council of Lower Canada had passed in 1837 to introduce British common law into the courts. Such gestures he knew would reassure the Canadians that their educational and legal systems would be preserved. He then visited Montreal and Quebec, where his respectful manner, his age, grace, and charm, as well as his fluency in French did much to win over the Canadians.

In Upper Canada Bagot took his role as ex officio chancellor of King’s College, Toronto, seriously. He urged an end to the numerous delays in opening the college [see John Strachan*], worked hard to find suitable professors in the colonies and in Britain [see Henry Holmes Croft*], and laid the college’s cornerstone on 21 April 1842.

Early that summer, in an effort to strengthen his executive, Bagot appointed Francis Hincks* inspector general of public accounts. His hopes that Hincks would bring with him the support of moderate reformers and that Henry Sherwood*, sworn in as solicitor general in late July, would rally tories to the administration did not materialize. By the end of the summer it became clear that the Executive Council would barely, if at all, hold the confidence of the assembly in the session due to begin in September. Bagot took the advice of such moderate executive councillors as William Henry Draper* and Samuel Bealey Harrison* that the ministry needed the support of the French bloc. On 10 Sept. 1842 he sent for Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* to discuss terms for his support in the assembly. The Canadian reform leader consulted with his ally, Robert Baldwin*, the most outspoken proponent of responsible government among Upper Canadian reformers. He returned the following day with a demand for four places in the council, including a position for Baldwin. Bagot, wishing to avoid any concession towards responsible government, replied that he could accept Baldwin provided he “consider himself as brought in by the French Canadian party,” not as the leader of the Upper Canadian reformers. He also offered fewer positions than the four demanded by La Fontaine, and on this point their talks broke down. At a meeting of the Executive Council on 12 September, Draper, concerned that this impasse might make possible an alliance of tory and Canadian opposition to the union, offered to resign and indicated that other councillors could be removed if it would help Bagot in his negotiations. He also threatened Bagot with mass resignations if the governor did not accept his advice. The following day Bagot offered La Fontaine the four seats he had demanded but La Fontaine surprised him by rejecting the offer.

Bagot suspected that La Fontaine’s refusal came after consultation with Baldwin and was calculated to force a complete reconstruction of the Executive Council along reform party lines. His fears seemed to be confirmed later in the day when Baldwin introduced a motion of non-confidence in the assembly and reiterated his demand for responsible government. This Bagot was determined to prevent. Hoping that the backbenchers would force a compromise, he had Draper disclose the terms of his second offer to La Fontaine in the assembly. After a lively debate the reform leaders indeed succumbed to the pressure of their followers and agreed to accept Bagot’s offer. Negotiations resumed on 14 September and were concluded satisfactorily. The reconstituted Executive Council eventually included La Fontaine and his supporters Augustin-Norbert Morin* and Thomas Cushing Aylwin*; Baldwin and his follower James Edward Small*; the moderate reformers Harrison, Hincks, and John Henry Dunn*; the tory Robert Baldwin Sullivan*; and the non-partisan Hamilton Hartley Killaly* and Dominick Daly*. Bagot’s skill and personal prestige had salvaged the principle of harmony and, since the new executive had not been formed exclusively along party lines, appeared to have staved off responsible government. Yet Bagot himself admitted to the colonial secretary that “whether the doctrine of responsible government is openly acknowledged, or is only tacitly acquiesced in, virtually it exists.”

In London, Peel was alarmed by Bagot’s concessions and by a public outcry fed by opposition claims that the government of the Canadas had been handed over to ultra-radicals and former rebels who would soon sever the British connection. Bagot, however, was defended by Murdoch, now back in England, and in time the cabinet came to accept the wisdom of what Bagot had called his “great measure.”

Bagot developed an amicable and productive working relationship with La Fontaine and Baldwin, but the strains of the first few months in office seem to have been too much for him. His health had been failing before he came to the Canadas. By late fall he was suffering from a combination of maladies and, too ill to play a prominent role in public affairs, he let much of the responsibility fall to La Fontaine and Baldwin The colonial secretary accepted his resignation in January 1843. His successor, Sir Charles Theophilus Metcalfe, assumed office on 30 March. By that time Bagot was too sick to return home. He died at the governor’s official residence, Alwington House, less than two months later

Bagot’s “great measure” remains the most important accomplishment of his brief tenure of office. He displayed therein a fine sense of parliamentary manœuvre and a firm management of men. He was the first British statesman to bring Canadians into the government of their country, and he thus put a decisive mark on the history of constitutional government in the Canadas. As for the American issues he had been expected to address, they had already faded in the wake of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of August 1842. Bagot deserves the credit, however, for advising the British that month to put an end to the dispute over the Oregon country before American settlement weakened their position. He did not live long enough to see his advice followed in 1845, but for this and also for his earlier contributions to British North American boundary negotiations his name and memory certainly belong to the long story of the “undefended border.”

MTRL, Robert Baldwin papers. PAC, MG 11, [CO 42] Q; MG 24, A13, B14; RG 8, I (C ser.). Egerton Ryerson, Some remarks upon Sir Charles Bagot’s Canadian government (Kingston, [Ont.], 1843). Statutes, treaties and documents of the Canadian constitution, 1713–1929, ed. W. P. M. Kennedy (2nd ed., Toronto, 1930). Burke’s peerage (1890). DNB. J. M. S. Careless, The union of the Canadas: the growth of Canadian institutions, 1841–1857 (Toronto, 1967). G. P. de T. Glazebrook, Sir Charles Bagot in Canada: a study in British colonial government (Oxford, Eng., 1929). Monet, Last cannon shot. Paul Knaplund, “The Buller–Peel correspondence regarding Canada,” CHR, 8 (1927): 41–50. J. L. Morison, “Sir Charles Bagot: an incident in Canadian parliamentary history,” Queen’s Quarterly (Kingston), 20 (1912): 1–22. W. O. Mulligan, “Sir Charles Bagot and Canadian boundary questions,” CHA Report, 1936: 40–52.

Cite This Article

Jacques Monet, “BAGOT, Sir CHARLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bagot_charles_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bagot_charles_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jacques Monet |

| Title of Article: | BAGOT, Sir CHARLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |