Source: Link

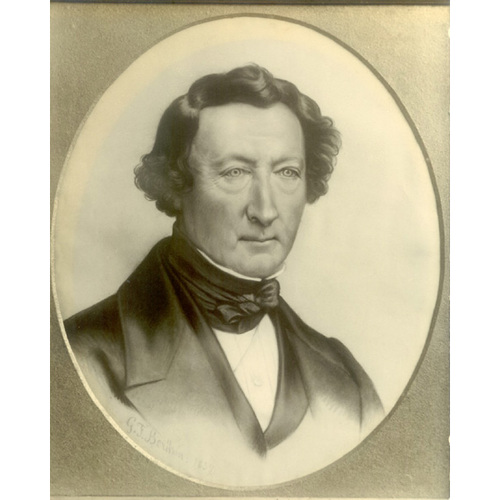

MACAULAY (McAulay), JOHN, businessman, office holder, newspaperman, justice of the peace, militia officer, and politician; b. 17 Oct. 1792 in Kingston, Upper Canada, son of Robert Macaulay* and Ann Kirby*; m. first 23 Oct. 1833, in Montreal, Helen Macpherson (d. 1846), sister of David Lewis Macpherson*, and they had six daughters and one son; m. secondly 1 March 1853, in Kingston, Sarah Phillis Young, and they had one daughter; d. there 10 Aug. 1857.

Young John Macaulay wanted for none of the advantages early Upper Canadian society could offer. His father was a loyalist and one of the earliest merchants at Cataraqui (Kingston). After his father’s death in 1800, John and his brothers, William* and Robert, were raised by their mother and uncle, John Kirby*, also one of Kingston’s leading merchants. The family seems to have been very close and affectionate. The Macaulays were well-to-do and had been left a decent inheritance and excellent connections. John’s particular legacy, as the eldest son in a social set that believed in the virtues of primogeniture, was the expectations and strictures of his mother. Educated by John Strachan* at his grammar school in Cornwall, Macaulay bore the imprint of these early years for the rest of his life. On one occasion Strachan reminded him, “Every person can make more of being good – the practice of the virtues is in every ones power.” In 1808 Ann Macaulay shipped John off to Lower Canada to improve his French. Although his letters to her are not extant, he was obviously unhappy and wished to return. His mother, however, was unwilling to indulge him and she upbraided the serious youth for being “whimsical and unsteady,” cautioning him not “to misapply your time that ought to be spent in study to fit you for the commerce of the world.”

One historian has suggested that Macaulay intended a career in law, like his school chums Archibald McLean*, Jonas Jones*, and John Beverley Robinson*. If true, it was not to be. By 1812 he had set up shop in Kingston as a general merchant and the following year was one of the 14 merchants who established, for the purpose of issuing bills in exchange for specie, the Kingston Association, the first, albeit rudimentary, bank in Upper Canada [see Joseph Forsyth*]. Macaulay became deputy postmaster at Kingston in 1815 and acted, as well, as ticket agent for the Kingston Amateur Theatre, agent for the Saint-Maurice ironworks, subscription agent for the New York Herald, land agent, and, in 1822, vice-president of the Kingston Savings Bank. Although little is known about the scope of his mercantile operations, he prospered; in 1834 Lieutenant Governor Sir John Colborne* described him as “opulent.” He was, primarily, a man of business until his entry into the bruising world of public politics and civil administration in 1836. Unlike his compatriots, Macaulay was a late comer to this arena, although it was not for the want of urging. In 1824 Robinson had tried to ginger him up, “You are one of the regularly bred, and You owe the State some service.” Temperamentally Macaulay was unsuited to the rough-and-tumble fray of electoral politics and he knew it. He had no ambition – or, more correctly perhaps, no liking – for such public exposure. But if his sense of his political role was circumscribed by that predisposition, it channelled him into other, and as important, activities.

Macaulay shared the conventional wisdom of the Upper Canadian élite on politics and society. Although there were periodic disagreements among them, there was consensus on the fundamentals. Macaulay was first drawn into political battle in reaction to Robert Gourlay*’s accusations of abuses by government and his calls for reform. In a letter published in Stephen Miles*’s Kingston Gazette during the summer of 1818, Macaulay expressed alarm at Gourlay’s “novel and alarming steps” – the provincial convention and proposed petition to the Prince Regent. In most respects, the letter is undistinguished, simply the commonplace utterances of counter-revolutionary toryism reacting to a “visionary reformer” and the “wild schemes of turbulent and factious men.” Naturally enough, Macaulay urged redress “in a regular and safe way” and preservation of the British constitution “in all its purity.” More important than his tory waxings was the image he drew of Upper Canada as a cornucopia of nature’s riches. Whether a full-scale myth or simply a metaphor for the province’s prosperity and potential, Macaulay’s statement that Upper Canadians were “the most happy people on the face of the globe, possessing a fertile country, which smiles like Eden in her summer dress, and a free Constitution of Government,” gave symbolic utterance to an inchoate and unlimited faith in the bounty of the province. Farming, development, and prosperity were cardinal articles of the élite’s tory faith. To be sure, it was a naïve belief, especially in one who could without trouble stub his toe on the outcrops of Laurentian granite north of Kingston. Indeed, reproach was not long in coming. Common Sense, most probably a pseudonym of Barnabas Bidwell*, derided Macaulay in the Kingston Gazette in July 1818 for his defence of a hierarchical society in which the “industrious poor” were bent under the yoke of the “rich and the affluent,” and he hooted at Macaulay’s image of the landscape, which was, in fact, a “teeming land choaked with rank and poisonous weeds, and your oozy swamps.”

The Gourlay agitation had a marked effect on Macaulay and not solely because of the Scot’s charges of illegality in the running of the post office at Kingston. Gourlay’s impact had demonstrated the potential of’ the press for fuelling, and confronting, extra-parliamentary agitation [see Bartemas Ferguson*]. Early in December 1818 Macaulay and Alexander Pringle purchased the Kingston Gazette, renamed it, and published the first issue of the Kingston Chronicle on 1 Jan. 1819. The newspaper brought Macaulay to the forefront of the provincial stage, in part by his publication of a torrent of letters from Strachan, Robinson, George Herchmer Markland*, and Christopher Alexander Hagerman* on a host of local and provincial issues. Macaulay, however, was no one’s cipher. At the outset of his editorship he rebuffed Strachan’s proffered pieces on land granting, the first evidence of a resolute, if at times quirkish, independence. On this occasion, Strachan recovered his poise and seduously fostered his former student by counsel and ministrations. Even so, further disagreements were in the offing. Macaulay had little use for the infamous Sedition Act of 1818 and the manner in which it was used against Gourlay, though he later took a harder line on the Scot.

The Chronicle was ostensibly an independent press – independence was the chief virtue of the politics of pre-industrial society regardless of political leanings. The journal soon became, as Robinson put it, a paper that gave the “highest satisfaction to every wellwisher of Church & State.” It was the first so-called administration paper, Robert Stanton*’s U.E. Loyalist and Thomas Dalton*’s Patriot being later examples. Macaulay’s paper lacked the rabble-rousing quality of the latter, which sought to popularize toryism and give it roots in the urban lower classes. But the particular interest of the Chronicle is not simply that it was the first. Macaulay had close ties to Robinson and Strachan – the rising stars in the administration of Lieutenant Governor Sir Peregrine Maitland – and by late 1820 Strachan, then a legislative and executive councillor, had mentioned the importance of the paper to the governor. Maitland was suitably impressed and felt it could be used for the publication of government accounts and advertisements. This favourable impression gave Macaulay direct access to the office of the lieutenant governor through his secretary, Major George Hillier*. By early 1821 Hillier was a conduit for the administration’s views on any number of issues of provincial or local importance. He would, for instance, report to Macaulay on parliamentary activities “from time to time in this loose way” and leave it for him to “dish up for the public according to your own taste.”

Privy to the confidential information of the small coterie of advisers to Maitland, Macaulay became the administration’s advocate. Although he had no use for the public world, he soon became what historian Sydney Francis Wise has called a “back room boy.” Publicly he decried the factionalism of politics yet he could be as partisan and manipulative as the men he inveighed against. During the election of 1820, for instance, Strachan was “much gratified” with Macaulay’s squibs against Barnabas Bidwell, whose possible election in Lennox and Addington would be “a disgrace to the Province.” Bidwell lost the election but was returned at a by-election on 10 Nov. 1821. Eight days later in a letter to Macaulay, Robinson suggested a petition against Bidwell. “I will say further,” the attorney general noted, “that if you have reason to believe, as I firmly do that the old Vagabond has solemnly sworn to renounce fore all allegiance to the King of Great Britain & that proof can be obtained of it I will go your halves in the expence of procuring a certificate of it properly authenticated, but this is of course as Judge [D’Arcy Boulton*] says sub rosa.” Macaulay must have worked quickly. Parliament met on 21 November and the following day Robinson moved for leave to bring up the petition of 126 freeholders of Lennox and Addington protesting Bidwell’s election on moral and legal grounds. Macaulay had, in fact, sent an employee to Massachusetts to get the documents suggested by Robinson. The costs were shared by Macaulay, Robinson, Strachan, Hagerman, and Markland.

Bidwell was expelled from the assembly in January 1822 by the slimmest of majorities. In the Chronicle Macaulay was aghast that “this grand triumph of the cause of correct principle and sound morals” had not attracted greater support in the assembly. Almost a year earlier Robinson had warned him to be “cautious not to speak too freely of the motions or proceedings of the House in yr. Editorial Articles.” Robert Nichol* moved a resolution condemning his editorial of 11 Jan. 1822 as a “malicious libel, and a breach of the privileges of this House.” It was carried with only Hagerman, then an assemblyman for Kingston, in dissent. Hillier reassured Macaulay that there was nothing to fear from the resolution and the issue was held over until January 1823. Hagerman, however, withheld Macaulay’s response to the speaker, explaining in February of that year, “I did not admire your style, it was more in justification than in excuse of your conduct and was therefore scarcely to be received as an apology.” After a resolution had been passed to the effect that the house had asserted its privilege and the author acknowledged his impropriety, Hagerman secured an indefinite adjournment of the debate.

To the tory mind, order was essential to the tranquillity and security of society and that order had its foundation in a hierarchical social structure, a belief which Macaulay articulated in a series of editorials in the Chronicle between 1819 and 1822. The “enemies of tranquility and good order” – restless agitators such as Gourlay or suspected democrats such as Bidwell – had brought Macaulay into the political fray with much force. In an early editorial he defended the relationship between natural inequality and political inequality; in short, he upheld the primacy of the rule of gentlemen. An unapologetic élitist, he quoted Blackstone’s amazement that only in “the science of legislation the noblest and most difficult of any” was “some method of instruction . . . not looked upon as requisite.” The prime example of such folly was the United States, where, Macaulay believed, “even the common street beggar thinks himself qualified to give gratuitous opinions, on the science of legislation, though his abilities and judgment have been totally inadequate to the task of devising ‘ways and means’ for keeping himself from rags and starvation.” Turbulence was natural to any society but organized agitation was essentially seditious and the work of unbalanced or disturbed minds. Casting a glance at Europe and the apparent widespread “love for a constitutional government,” he wished success where it could be gratified by “the blessings of rational liberty,” but he feared the desire was “mixed up in many instances, [with] a spirit of Jacobinism or Radicalism, a sort of wild theory which can never be reduced to practice.” In contrast, the balanced or mixed constitution of Great Britain hallowed rational liberty. But the key to its preservation was balance. Democracy, not monarchy or aristocracy, threatened Upper Canada and Macaulay had “no particular penchant” for it, even in its “most alluring shape.” He was particularly alarmed by the tendency evident in some of the American states to push the elective principle to extremes and was chary of a constitution that allowed “all men except perfect vagrants and mendicants and slaves” to vote. Democracy meant that “the interests of the public are often sacrificed to the furtherance of private interests – and that there is too great a temptation for men in official situations, to profit by the passing opportunity of grasping at the publican loaves & fishes, of thus paying due respect to that venerable maxim which suggests the wisdom of making Hay while the sun shines.”

Macaulay’s defence of the balanced constitution was real inasmuch as he upheld the independence of each of its constituent parts, including the House of Assembly. He disapproved, for instance, of a suggestion to introduce executive councillors into that body as an “impolitic, unwise & odious innovation on the Constitution.” He was concerned “that the democratical principles of our neighbours are making large inroads on the purer democratical principles of our constitution – & that consequently . . . the influence of the crown has diminished & is diminishing [and] it ought to be increased.” Rejecting Jonas Jones’s tag of “a High Monarchy man,” he admitted to “being a little aristocratical in sentiment.” He favoured longer parliaments (hence fewer elections) and a much higher property qualification for voters. “I take it as an axiom that no man in this country who is worth less than £500, is fit, to make laws, or to be trusted with a power of meddling with the Laws fixing the rights of property.”

More important than Macaulay’s defence of a balanced constitution was his use of the Chronicle as an organ for popularizing the idea, which had been taking shape in the Canadas since the 1790s, of economic improvement and development. The late 1810s ushered in economic depression, extraordinary concern over the commercial impact of a canal system in New York State, and the discontent of the Gourlay episode. These developments cohered in Macaulay’s mind. As a merchant and resident of Kingston, which was more intimately connected to the Laurentian trade than York (Toronto), he had a more practical grasp of the mechanics of the Upper Canadian economy than a Strachan or a Robinson. He was the first to sense and then to articulate the imperative of wedding prosperity to the constitution, and the relation of both to a contented polity. Here was a particularly British North American faith, a combination of British conservatism and American technology, first expounded in Upper Canada by Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe* and given quintessential expression in Nova Scotia in Thomas Chandler Haliburton*’s Sam Slick novels. In the shadows of depression and discontent, Macaulay and his friends, particularly Strachan and Robinson, put forward, in a somewhat desultory fashion, a strategy for provincial economic development which became increasingly identified with the governing tory élite and which it quickly shaped into a legislative priority of first importance.

The underlying assumptions were straightforward. Upper Canada’s economic character was fundamentally and immutably agricultural. Upon the province had been bestowed the rich bounty of providential dispensation; men had but to turn their hands to cultivation to reap prosperity. Macaulay and his set loathed what Macaulay called the “lonely forest and dreary wilderness,” which indicated the absence, rather than the presence, of civilization. Viewing society as organic, he could despair of antagonisms between its various orders and argue that its fundamental harmony could be improved by agricultural societies. These, he believed, would not only introduce and promote new agricultural methods among farmers but would excite a “spirit of emulation and enterprise” among them and demonstrate “how far their interest is connected with that of commerce, & how much depends upon them for promoting the general prosperity of this new country and their own advantage at the same time.”

The basic strategy for development was to link the agricultural regions bordering lakes Erie and Ontario to markets in Great Britain. The major obstacles were Niagara Falls and the rapids of the St Lawrence River. Thus, the chief requirement was canals connecting Prescott to Montreal and linking the two lakes, thereby opening up the province’s economy. Much is made by historians of the anti-American impulses behind the toryism of Upper Canada, but men such as Macaulay were awed by American achievement, especially in the field of canal building. In his editorial of 29 Jan. 1819 he praised New York governor DeWitt Clinton for his remarks on the “grand internal improvements” of his state and hoped parliament would “make some efforts towards accomplishing the projected improvements on the navigation of the St. Lawrence.”

In a series of long letters on internal improvement published in the Chronicle in March 1819 (probably written by Strachan), the drum beating for economic development began in earnest. The letters suggested an innovative and positive role for the press as promoter of improvement rather than harbinger of discontent. Later in the year a discursive essay on the “happy art of anticipation,” attributed to Robinson, defined the progressive, commercial nature of American civilization. The Yankees regulated “all their schemes and plans, not according to what is, but to what they hope and suppose will be.” Here was the path for Upper Canada. Heretofore “great designs and brilliant specifications” only elicited ill favour from the populace in a colony that offered “fair scope” for anticipation. “Those who venture to shew a little public spirit and rational enterprise, will assuredly not be disappointed in the result of what they undertake.”

In editorial after editorial, Macaulay returned to this theme, offering a host of suggestions and policies on topics such as canals, imperial duties, manufacturing, farming, banking, provincial tariffs, and regulations on trade. Within the framework of tory assumptions, he put forward, in collaboration with his friends, a positive role for government in fostering prosperity by means of important public works and complementary statutes. The depression was only temporary and Macaulay, following the analysis of Clinton, looked to “the enterprising spirit of the country” supported by the provincial treasury for a quick and sustained recovery. A comprehensive program of internal public works – canals mainly – would provide the fundamental framework. The economy was essentially agricultural, but it must be diversified, the range of native manufactures increased, and the dependence on imports reduced. Such independence from the American republic was necessary for the prosperity so keenly sought.

In 1818 a joint Upper and Lower Canadian committee had recommended the construction of canals on the St Lawrence equal in size to those in New York State. Progress was slow, however, and Macaulay lamented the delays in completing the Lachine Canal, begun in 1821, “the want of which is so much felt by every person whose produce descends to the Montreal market.” In 1821 the Upper Canadian assembly took a major, albeit fledgling, step to come to grips with the province’s economic destiny when it formed a select committee to examine the agricultural depression and the collapse of British markets. The resulting report, probably the production of the committee’s brilliant and mercurial chairman, Robert Nichol, provided a framework for economic development which would last a generation: the linking of agriculture, imperial markets, and canals. Yet although it set the strategy for the province in motion, its tone was less than hopeful in view of the “limited power and deficiency of pecuniary means of the Provincial Legislature, [which] almost preclude the possibility of legislating on the subject.” Recommendations on the specifics of canals, the report stated, should be the purview of a commission on the improvement of internal navigation. An act providing for such a body was approved on 13 April 1821. It was an auspicious moment in provincial history. Maitland, in his remarks at the closing of parliament the next day, called it “the commencement of an important undertaking eminently calculated to advance the prosperity and greatness of Upper Canada.” It was exactly this newly developed sense of economic possibilities and an increasingly interventionist government that provided an outlet for Macaulay’s now evident abilities.

Within the limited political circles of Upper Canada, Macaulay quickly gained, and would long retain, a reputation as an authority on the economy and public improvement. In early December 1822 Strachan, a director of the newly established Bank of Upper Canada, offered him the job of agent at Kingston. He doubted whether it would be “wise to continue Your Paper” but stated, “We have so much confidence in you that we shall part with you with the greatest reluctance.” Strachan took it “for granted” that his former student would accept and proceeded a week later to offer him another plum, the post of secretary to James Baby*, who had been appointed an arbitrator for the division of customs duties between Upper and Lower Canada. A gentleman of charm and affability, Baby was, according to Strachan, “rather slow of apprehension and will proceed entirely by your superior intelligence as you will communicate it in that modest unobtrusive manner which will still leave him in his place.” Strachan urged him to accept the position, as “I have not seen a chance of bringing you forward in so honourable a way since I had any thing to say in the Govt. nor will such an opportunity soon offer again.” Macaulay accepted both positions and at the end of 1822 gave up the editorship of the Chronicle, although he almost certainly retained a proprietary interest in it for a few more years.

Macaulay early showed a disinclination to remain a merchant. He yearned for independence and probably for the security of a fixed income. The bank agency would help but he had also sought the rumoured appointment of deputy postmaster general for Upper Canada. In March 1823, however, Strachan warned him that William Allan, the bank’s president, had reportedly lost his fortune and “if Allans loss be what it is conjectured you are better off than he is.” Meanwhile Macaulay offered his resignation as agent of the bank over a row with its head cashier, Thomas Gibbs Ridout*. Strachan intervened to mollify him, reminding him that a permanent office might soon be set up in Kingston and he would become cashier there. Allan offered the full backing of the directors; Macaulay withdrew his resignation. The support for Macaulay was not simply an act of favouritism. The young Kingstonian had enormous ability and both Hillier and Strachan intended to make full use of it. Macaulay’s work on customs arbitration, which lasted until the summer of 1823 and possibly later, was vital in the short term. His report to Maitland on the matter drew praise all round; Strachan pronounced it “simple clear and modest.” A fervid advocate of union with Lower Canada as the cure for the upper province’s financial ills, Macaulay did not think the Canada Trade Act of 1822 went far enough in expanding Upper Canada’s jurisdiction in matters of revenue sharing with Lower Canada and economic development. Still, his report settled the issue of arrearages and established, for purposes of arbitration under the act, a new formula for revenue sharing.

Macaulay’s work for the commission on internal navigation, to which he had been appointed in the spring of 1821, had a far greater impact on provincial policy. Ever concerned about propriety, Macaulay wondered about potential conflict with his work on the arbitration. Both Strachan and Hillier, who was “quite anxious” on the matter, assured him the two positions could be reconciled “very easily.” By September, Macaulay had become president of the commission and hence directed its work. Its various reports, the first of which was published in 1823, were submitted in 1825 to a joint committee on internal navigation, co-chaired by Strachan and Robinson. It published all the reports a year later. The joint committee accepted them “as containing the best, and in truth, the only satisfactory information” as to the means of improving internal navigation and of establishing parliamentary priorities on which canals to proceed with and on what scale.

In the last issue of the Chronicle edited by Macaulay, on 27 Dec. 1822, he had reviewed favourably “the manifest improvements effected in the internal condition of Provincial affairs with the last four years,” but found scant cause for celebration when he compared Canadian progress to public works under way in New York. In 1825 he marvelled at the change that had taken place in popular attitudes, a transformation that owed much to the efforts of Strachan, Robinson, and especially Macaulay. Surveying the past seven or eight years he pronounced in the commission’s report that “within this short period . . . is to be dated the happy nativity of that spirit of public enterprise, which . . . is destined to guide and quicken our march in the highway of prosperity.” Major concern about the ability of the province to finance large-scale public works disappeared, for a decade at least, after Nichol’s death in 1824. Robinson, who later claimed “the glory of laying the foundation of our public debt,” had broken the psychological limits with his 1821 bill providing for the deficit financing of arrearages in militia pensions. The province consequently backed into deficit financing and the use of debentures but, once adopted, they were allotted almost exclusively to the advantage of public works, particularly canals. A concrete manifestation of this change came in 1826–27 when the province lent £75,000 to the Welland Canal Company [see William Hamilton Merritt*]. A few years later the faith in canals became a mania. The man primarily responsible for the development of this climate of opinion was John Macaulay.

His influence, now that his newspaper was in the background, stemmed from his counsel on local and provincial matters, his proven capability and intelligence in handling committees and preparing reports, and his participation in local institutions. Hillier, for instance, often consulted him on matters such as the appointment of coroners and sought his aid in placing certain items in the Chronicle. Locally Macaulay was associated with a host of lay, benevolent, and religious organizations. He was, as well, a steward for the Kingston races, a trustee of the Midland District Grammar School, a leading magistrate and chairman for many years of the district’s Court of Quarter Sessions, president of the mechanics’ institute, a member of the building committee and later warden of St George’s Church, and an officer in the local militia. His pursuits were all in addition to his business, the bank, the post office, and his work for the government. Moreover, Macaulay generally attended meetings regularly, participated actively, and offered clear, simple, and constructive suggestions.

In 1828 he suffered a bitter disappointment. The collectorship of customs at Kingston became vacant upon Hagerman’s temporary elevation to the Court of King’s Bench. That summer Macaulay anxiously solicited the appointment through Hillier, Robinson, and Strachan. He wrote to Robinson: “I have fagged for years in editing a paper – the only one which defended the administration at the time, & though I had great trouble, I had not profit – and on every occasion I have endeavoured to make myself useful – not particularly . . . from any idea of reward, for that I never did think of . . . as from a feeling that I was acting rightly. . . . The place in question peculiarly comports with my situation & views. . . . It is the only one I care about – My ambition rises no higher[.] If I am disappointed, it is for the life – and the mortification will be severe.” It was. The new lieutenant governor, Sir John Colborne, gave the job to Thomas Kirkpatrick* and, more important, Robinson had been unable, for complicated but proper reasons, to support Macaulay’s application. Robinson had reminded his friend of the burden “of being thought able to render services to my friends which are in truth beyond my power.” Strachan pointed out to Macaulay in December 1828 that the reasons for his rejection had their origins in Maitland’s administration: “Nothing could be worse in taste and heart than Sir P. or rather Perhaps Col Hilliers conduct for the last year in the way of appointment.” Though Maitland, in a letter to Colborne in March 1830, would describe Macaulay as “a gentleman . . . [of] superior talents and information . . . capable of rendering to the Province services of the highest order, and whose claims . . . I should . . . certainly have considered as irresistible,” it was clear that a misunderstanding of Maitland’s intentions had transpired.

In the aftermath of the political crisis wrought by the imbroglio surrounding Judge John Walpole Willis* and the election of radicals to the tenth parliament (1829–30), Macaulay became increasingly disgusted with politics. His friends wanted him at York and in one of the councils. Early in 1830 Hagerman, a favourite of Colborne, discussed with him Macaulay’s elevation to the Legislative Council. In 1831 Colborne appointed 13 men to the council including Zacheus Burnham and James Crooks. Strachan, who quickly fell from favour in Colborne’s administration, reported to Macaulay that many people commented that he “would have been worth them all.” Through the early 1830s Macaulay was dispirited yet entranced by the political trends of society in Europe, Great Britain, and the Canadas. He was certain that what seemed to be movements to separate religion and education, church and state, had proven that “infidel and democratic ideas are in unison and are spreading far & wide.” Early in 1832 Strachan and Macaulay discussed the usefulness of sending a representative to England to discuss with authorities there the problems of the colony. Strachan judged him “better fitted” to perform the task than Robinson, Hagerman, or Jones; “the truth is you are the very best political writer in the Province,” the archdeacon confided to Macaulay. In fact Strachan considered Hagerman and Jones unable to handle such a task satisfactorily either “singly or combined.” Hagerman and Colborne discussed the council’s composition again in April 1832 and the lieutenant governor stated his intention to recommend Macaulay before leaving office. Although the recommendation was not immediately forthcoming, Colborne had, nevertheless, changed his mind on the usefulness of Maitland’s old advisers, at least Robinson and Macaulay. Returning to the public harness, Macaulay in December 1833 wrote to his wife that he had handed in reports on a lighthouse, the provincial penitentiary, and the Welland Canal, and was working on two more, a major report for the St Lawrence canals commission and one on the northern section of the boundary between Upper and Lower Canada. As well, he was assisting in the revision of the province’s road laws.

By the mid 1830s the political temper of the province had changed considerably from that of a decade earlier. Macaulay had changed too. His ambition was no longer confined to Kingston. To accept high office entailed moving to Toronto and up to this point in time he had been unwilling to do that, probably out of personal reserve and his close attachment to his mother and uncle. What had changed? First, he was now married with a family, who could and would accompany him. Secondly, he was keenly aware of Kingston’s economic decline. His once breezy confidence in his beloved town’s future was being eroded by the slow development of its hinterland and by the town’s loss of commercial leadership to Toronto. Late in 1834 Macaulay had taken the lead in suggesting manufacturing as the basis for a prosperous municipal future, but he was all too aware that the possibilities were bleak. Finally, it is probable that the cholera epidemic of 1834 had brought home the vulnerability of human life. In short, he was by 1835 ready to make a change, unthinkable a decade earlier.

The move to Toronto took place in two steps. The first was Macaulay’s appointment to the Legislative Council, which was announced in May 1835. The possibility of the surveyor generalship was mentioned indirectly but nothing happened initially. There were rumours that Macaulay might not take his seat “in Consequence of the Directors [of the Bank of Upper Canada] being against your absence from the office,” but this obstacle was quickly scotched by William Proudfoot*, the bank’s president. On 3 Oct. 1836 Macaulay was offered the surveyor generalship with a salary of £600 and a small fee schedule; he was, almost simultaneously, nominated a customs arbitrator for the province. Three days later he accepted both positions. Like others, including friends such as Robert Stanton, Macaulay was “never . . . more taken by surprise than on this occasion.” To William Allan he explained that he was not an office hunter. He had no need of employment and would not gain financially by the move. Indeed, his major concern was financial loss. His present income was £650 to £700 and “I occupy my own House in a town where domestic expenses, are far more moderate.” It would be a “trial” being separated from his home, family, and town. Still, political affairs had changed with the election of 1836, which produced a tory majority [see Sir Francis Bond Head*], and the “King’s Service should always be looked up to as an Honourable Service, and be the object of proper ambition with all.”

Macaulay set off immediately to take up his new duties. In spite of a demanding work schedule, to say nothing of finding permanent accommodation for his family, Macaulay was homesick. He had a busy social calendar, which he found somewhat tedious, but was buoyed up at discovering his income would be about £800. The state of affairs at the surveyor general’s office was chaotic [see Samuel Proudfoot Hurd] and he predicted it would “require my steady attendance during office Hours & some labour for many months to see arrears of work brought up & the office placed in an efficient state.” Indeed the magnitude of the problems was such that they interfered “much with my Legislative Duties. . . . I find that my life will be devoted to the remedying of the injuries inflicted on individuals by the careless work of the early Surveyors.” A typical day when parliament was in session saw Macaulay rise before 8 o’clock, get to the office by 10, work till 3, go to the council chamber until adjournment, return to quarters about 5:30, then dine, write, and read until retiring between 11 and 12. He disliked the round of parties and entertainment that marked the gentle life of the capital; on some occasions he was not invited.

In March 1837 the Bank of Upper Canada wanted to know whether he would resign his cashiership at Kingston. He had put off making a decision on permanent residence in Toronto while awaiting confirmation of his surveyor generalship from London. Although his salary was greater, he discovered living expenses were higher in Toronto and his duties there were “far more responsible” than he had expected. The exigencies of the surveyor generalship, such as the need to supervise his six clerks constantly, made it “a disagreeable office” and his inability to take leave when he wanted to amounted to “gilded slavery.” Both his mother and his uncle urged him to return to Kingston. None the less, he could not make up his mind and remained “in a state of great doubt and perplexity.” A superb administrator and councillor, Macaulay found “on the other hand I am not cut out for a Courtier, & do not like attending at levees – or being liable to the intrigues & jealousies of a Provincial Metropolis.” He remarked to his wife, “A Medium elevation we shall prefer to the tip top rank as well for comfort, as interest.” He remained close, however, to Robinson, Hagerman, and Markland, but “several of the great men here have never called on me! . . . others are all frigid.” By April he had decided to remain for the present, “I find every one recommends it.” He was beginning “to take a fancy to the Employment & will probably in time like it.” The surveyor generalship was nevertheless “a sadness & requires a thorough Reform.” He hoped to set it right within a year or two, but it is not known if he ever achieved any administrative reform. Towards the end of April 1837 Macaulay decided to stay in Toronto. Even his mother had conceded that he could not give up his post with honour. At the end of the month he returned to Kingston and resigned his office with the bank. Committed to the administration, Macaulay was quickly burdened with more work. On 25 May he was named, along with John Solomon Cartwright* and Frederick Henry Baddeley*, to carry out the provisions of an 1836 statute to survey the country between the Ottawa River and Lake Huron.

During the summer of 1837 Macaulay was preoccupied with parliamentary affairs, particularly Head’s refusal to allow banks to suspend specie payments in response to the international commercial crisis of 1836–37. He was also discovering the “great expence” attendant upon living the gentle life. He gave up an “extensive and aristocratical premises” rented from John Henry Dunn for a “snug” brick house on College Avenue. In order to preclude suspicion that he had used his “office to my own advantage,” he sold off, at a premium, land he had purchased on speculation. Finally, in mid September, he received confirmation of his appointment as surveyor general. Through the fall he busied himself with decorating and furnishing the family home. After almost a year of “bustle and discomfort, and expence” he looked forward to a respite. The political horizon, however, looked stormy and he confided to his mother that unless conservatism gained ground in England, “our general political prospects will become gloomy.” What worried him was radicalism in Lower Canada. The only hope was to act decisively, annex Montreal to the upper province and the Gaspé to New Brunswick, and leave the French with a military governor and a council to make laws. The effect would be to “render Canada quite English at last.”

Macaulay never expected an armed uprising in Upper Canada. When it came in December 1837 [see William Lyon Mackenzie*] he considered it “a worse than Catalinian rebellion.” Its defeat was a narrow “escape from frightful miseries.” In the immediate post-rebellion period he expected “great changes in the Government of these colonies.” By this time too his unqualified faith in deficit financing and public debt had been transformed. He discerned “the elements of a new sort of opposition” in the assembly and, like William Allan, feared the government’s “heedless” practices in money matters. A particular and prescient apprehension was his observation that “great political discontent will result from this heavy debt.” The future was “uncertain” and the province “can never return to our former state of security & repose.” He saw the debt driving the province straight into union with Lower Canada, an end which he now deplored.

Macaulay applauded the initial actions taken by Head’s successor, Sir George Arthur, particularly the execution of Samuel Lount* and Peter Matthews* in April 1838. Arthur had retained Head’s secretary, John Joseph, but felt the need for a new appointment. In May he broached the subject with Macaulay, who was reluctant. Meanwhile, George Herchmer Markland’s hold on the inspector generalship was, as Robinson put it, “shaking in the wind,” and Robinson urged Arthur to appoint Macaulay, the “best man” in the province, to that office. On 16 June, Macaulay was gazetted as Arthur’s civil and private secretary, with Robert Baldwin Sullivan succeeding him as surveyor general. In spite of Markland’s strong rearguard action to absolve himself, his homosexual activity brought him down. He resigned on 30 September and Macaulay acceded to the inspector generalship the next day. He was secretary for a year, the most able and powerful secretary since George Hillier. It is difficult to assess the extent of Macaulay’s influence. What is certain is that he brought order and organization to the office, kept Arthur thoroughly briefed on all aspects of the administration, and may have given him the idea to initiate a parliamentary investigation in 1839 into the state of government offices.

Macaulay had “great dread” of the consequences of the much-touted remedies for the Canadian crisis – union and responsible government. None the less, he voted with the majority in the Legislative Council in favour of union on 12 Dec. 1839. There had always been a quirkish bent to his actions; his reasoning seemed odd to friends such as Robinson. With far less experience in government administration, Macaulay believed it “my duty to give up my own opinions, & do all in my power to forward the views of the Government whose Servant I am” – a view which contrasted sharply with Arthur’s statement that crown officers in Upper Canada “were left by the Government at liberty to act as they pleased, in their Legislative Capacity.” The age of gentleman administrators was over; Governor Charles Edward Poulett Thomson*, later Lord Sydenham, would bring them to heel if necessary, as he had Hagerman, and Macaulay knew it. His decision caused a rupture with Strachan, who thought “such a principle carried out would justify the Servants of Queen Mary in condemning Ridley Latimer Cranmer &c to the stake.” One by one the boyhood friends who had been so close to power since the War of 1812 were deprived of their political influence. Jones, McLean, and Hagerman joined Robinson on the bench; only Macaulay retained office. Sydenham had understood the position of inspector general would evolve into that of “a kind of Finance Minister” and judged Macaulay to have “first claim to it, as well as from his Character . . . as a Man of business.” But because of the new stipulation that ministers must have seats in the assembly, Macaulay resigned the post in June 1842, not wishing “to attempt to play a part for which neither art nor nature has qualified me.” He retained his seat on the Legislative Council, however, until his death.

During the last months of Arthur’s administration, in early 1841, Macaulay had prepared for his return to Kingston, the new seat of government, and eventually to private life. By January 1842 Arthur had forwarded Macaulay’s last official report, a massive general report on Canada, to London and wrote concerning his future employment. Macaulay hoped at least for a pension following his resignation that June but was humiliated by Sir Charles Bagot*’s offer in August of the shrievalty of the Midland District. He continued to press his claim for some years and was finally rewarded with the collectorship of customs at Kingston on 31 Dec. 1845. A stipulation was added that he give up his seat on the council. Macaulay refused and resigned the customs office the following May.

Macaulay was independently wealthy and spent the remainder of his years superintending a large portfolio of investments and speculating in land. He was an agent for several companies and, for a few years in the 1840s, was president of the Commercial Bank of the Midland District. In spite of the comparative ease of his public life, his domestic life was a series of tragedies. His first wife was a carrier of tuberculosis. During the 1840s Macaulay lost his infant triplets, his wife, his daughter Naomi Helen, his uncle, and his mother. Early in 1852 he received a telegram from his eldest daughter’s finishing-school in England asking him to take her home. Ann was too ill to stand the voyage back. The distraught father took a suite of rooms and watched his beloved daughter die. During this period he kept a diary which provides the only real glimpse of the repressed emotionalism that was John Macaulay’s. This kind and loving man, once scolded by his mother for spoiling his daughter, sat at her bedside talking and reading the Bible to her. This man, so deeply conscious of propriety, could only find relief by running in the streets while she slept, until he dropped from exhaustion. Macaulay was sustained, although his spirit was blasted, by an unfaltering faith that “God will be the strength of my heart and my portion forever.” The following year he married the daughter of Lieutenant-Colonel Plomer Young*, assistant adjutant general of the Kingston garrison. In October 1855 Macaulay suffered a stroke. Two years later he died in Kingston.

Macaulay’s name rarely, if ever, appeared in the reform critiques of the so-called “family compact.” Because he shunned the electoral world, he never acquired the prominence of Robinson, Hagerman, or Jones; because he avoided the councils for so many years, he lacked the profile of a Strachan or a Markland. Not a permanent resident in Toronto and not given to ostentatious living, he could not be compared to a Henry John Boulton* or Samuel Peters Jarvis. Indeed, men such as William Allan, who lacked Macaulay’s political clout and presided over less important institutions, have been considered by most historians to be much more important. But Macaulay probably ranks close to Robinson and Strachan and certainly surpassed the others in terms of his ability. Possessed of an agile, analytical mind, a clear writing style, a genius for organization and administration, a conscientious temperament, and a capacity for hard work, he was an indispensable figure who forged and popularized many of the key, and enduring, policies of successive administrations from Maitland to Arthur. His early and longstanding concern with the development of a provincial strategy for economic prosperity was an embodiment of the consensus that underlay the political, social, religious, national, and geographical solitudes of Upper Canada.

[The major source of information on John Macaulay is the collection of his papers held in AO, MS 78. The Macaulay papers held at the QUA relate mainly to his business affairs. Other major archival sources include the Upper Canada Sundries (PAC, RG 5, A1); the Colonial Office correspondence (PRO, CO 42); the William Allan papers at the MTL; the Robinson and Strachan papers at the AO (MS 4 and MS 35 respectively); and the records of the Commission for Improving the Navigation of the St Lawrence (PAC, RG 43, CV, 1). Among printed primary sources, the Arthur papers (Sanderson), and the Kingston Gazette (1810–18), Kingston Chronicle (1819–33), and Chronicle & Gazette (1833–47), are especially useful.

Macaulay’s official reports may be found in the appendices of the Journal of the House of Assembly of Upper Canada, the most important of which were also published separately as U.C., Commissioners of internal navigation, Reports of the commissioners of internal navigation, appointed by His Excellency Sir Peregrine Maitland, K.C.B. &c. &c. &c. in pursuance of an act of the provincial parliament of Upper-Canada passed in the second year of his majesty’s reign, entitled, “An act to make provision for the i[m]provment of the internal navigation of this province” (Kingston, [Ont.], 1826). His statement on Kingston’s economic ills was published in pamphlet form as The address delivered by John Macaulay, esq., to the public meeting convened in Kingston, Dec. 2nd, 1834, to “consider the expediency of ascertaining by a survey of the country between Loughborough Lake and the town, and also between the town and the Rideau Canal, the practicability of establishing water privileges at Kingston” (Kingston, 1834).

Genealogical and historical information on Macaulay’s family is provided in Margaret [Sharp] Angus’s article “The Macaulay family of Kingston,” Historic Kingston, no.5 (1955–56): 3–12. S. F. Wise’s seminal article, “John Macaulay: tory for all seasons,” in To preserve & defend: essays on Kingston in the nineteenth century, ed. G. [J. J.] Tulchinsky (Montreal and London, 1976), 185–202, is a superb analysis and account of Macaulay’s Kingston career. My own thesis, “Like Eden in her summer dress: gentry, economy, and society: Upper Canada, 1812–1840” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1979), emphasizes Macaulay’s role as a promoter of a provincial strategy for economic development. r.l.f.]

Cite This Article

Robert Lochiel Fraser, “MACAULAY (McAulay), JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 28, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macaulay_john_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macaulay_john_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert Lochiel Fraser |

| Title of Article: | MACAULAY (McAulay), JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | January 28, 2026 |