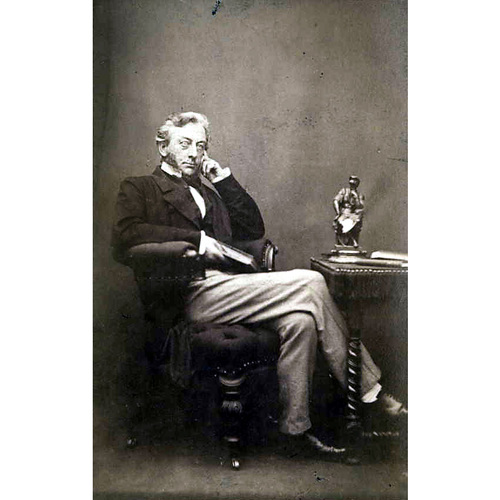

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

WILLIS, JOHN WALPOLE, judge; b. in England, 4 Jan. 1793, son of William Willis and Mary Smith; d. 10 Sept. 1877 at Wick House, Wick-Episcopi, Worcestershire, Eng.

William Willis died in 1809 leaving little estate and John Walpole rose by a combination of ambition, legal talents, and charm. He published his first legal work in 1816 and was called to the bar the following year. Willis’ interest in equity led to the publication in 1820 of a book that long remained an authority, and of a third work in 1827. His increasingly successful practice of the law was matched by a profitable advance into established society. These interests converged in 1823–24 when Willis was retained by the 11th Earl of Strathmore. In August 1824 their association led to his marriage to the earl’s elder daughter, Mary Isabella Bowes-Lyon, aged 22.

As a successful barrister and an authority on equity, Willis might have thrived indefinitely amid the efforts of Sir Robert Peel, as home secretary, to encourage the codification and moderation of English civil law and commercial law. But marriage to Lady Mary did not guarantee solvency or harmony. She brought no great dowry. Her life with Willis in Hendon, a quiet London suburb, offered little excitement; his limited means meant that his mother and sister were forced to share their home. Lady Mary’s consciousness of her rank appears to have grown, rather than diminished, following her marriage; her ambitions and the other financial and professional demands of Willis’ career were propelling him forward at a forced pace.

In 1827 the Colonial Office played briefly with the idea of pressing upon Upper Canada some of the current British legal reforms and of establishing a court of chancery through which remedies could be sought in equity. The Earl of Strathmore suggested that his son-in-law could grace that new bench with authority during the period of necessary adjustment. The reform was not yet finally settled, but on some loose understanding Willis accepted an interim appointment as junior puisne judge on the province’s Court of King’s Bench. Willis, with the entire Hendon ménage, arrived in York (Toronto) on 18 Sept. 1827. He was to be in Canada only nine months – less than half of Robert F. Gourlay*’s stay – but he would cause nearly as much alarm in official circles and stir the reform-minded at a decisive moment in their organization.

Willis discovered immediately that the governor, Sir Peregrine Maitland*, and his Executive Council questioned the Colonial Office’s flirtation with chancery. The attorney general, John Beverley Robinson*, and other Family Compact lawyers, including the solicitor general, Henry John Boulton*, differed over important details of the plan; Maitland’s strong will, thus reinforced, gave way only slowly to Whitehall’s proposals for a provincial enabling act. Robinson was prepared to accede to the proposal and even entrusted the drafting to an opposition lawyer, Dr John Rolph*, but Willis over-reached himself in attempting to force the pace of negotiations. The Reformers were anxious to bargain with the government by log-rolling – an equity court in return for a more independent judiciary. Willis abandoned his natural alliance with Robinson to consort with four lawyers who were then chief opposition spokesmen – Rolph, William Warren Baldwin*, Robert Baldwin*, and Marshall Spring Bidwell. Despite such advocates, Willis’ bill was emasculated and finally abandoned in the Tory assembly. Meantime, the imperial law officers had advised Whitehall not to press the matter further. Thus, the junior puisne judge was forced to reassess his prospects in the less familiar field of common law and in a provincial society.

At the outset Willis and his wife had been warmly accepted into York’s small circle. If Lady Mary thought her charms wasted, Willis quickly joined the round of parties and fashionable charities with the confidence that had served him at home. This goodwill, however, was soon squandered. Willis’ appointment had been deeply resented by aspirants such as Robinson, Boulton, and Christopher Hagerman*, who had prepared themselves through years of service in the common law and in Upper Canada’s legal system. Willis’ contempt for their abilities was expressed plainly, as was his poor opinion of his two superiors on the King’s Bench, Chief Justice William Campbell* and Levius Peters Sherwood*. In part Willis’ cause was sound: he argued, for example, that punishment in criminal cases was inhumane by contemporary English standards. But, by flaunting his own lack of factional spirit, he made the case for equity seem like a call for purity. Neither a demagogue like the earlier Judge Robert Thorpe*, nor a firebrand like Gourlay, he, with his charm and plausibility, seemed a more formidable opponent. Moreover, Governor Maitland’s wife, daughter of a duke, saw a threat to her social position from an earl’s daughter. These social and professional conflicts had developed so quickly that an open conflict must arise when Willis, after being resident only a few weeks, applied, in rivalry with Robinson, for succession to the chief justice’s seat.

On 11 April 1828, taking advantage of the absence of his two colleagues, Willis behaved extraordinarily while presiding over the libel trial of Francis Collins*, editor of the Canadian Freeman. Collins had sought the latitude customarily accorded those appearing without counsel, but Willis permitted and even encouraged him in a prolonged, irrelevant attack upon the law officers, Robinson and Boulton. On Robinson’s interjection, Willis presumed to question from the bench Robinson’s entire record of public office, threatening to make “a representation . . . to His Majesty’s Government.” As John Charles Dent* concludes, “Judge Willis seems to have been wrong in his law, wrong in his etiquette, wrong in his temper, and wrong in his construction of judicial amenities.”

By now, however, an impending general election invited hyperbole and postures of convenience. Maitland hastily assured Whitehall that because no one had before protested against “the laws, or the manner in which they have been administered, I must conclude that the people are content with both.” On the other hand, “the people” – including the most notable Reform lawyers – had already decided for Willis. Memory of the application of the sedition act to Robert Gourlay and Barnabas Bidwell* was fresh. Willis’ legitimate concern for the laws, however, threatened to give way to demagogy – an easy trap for a man of his vanity.

On 16 June Willis displayed a sensitivity for legal technicalities that would not have served him on 11 April by declaring that the act establishing King’s Bench required the presence of the “Chief Justice, together with two puisne justices.” Campbell was still absent on leave, as legal and administrative officers had frequently been of necessity in the past. Willis now presumed to cast doubt upon the entire legal foundation and record of the court for the past generation. The technicality needed to be met: the Baldwins refused to pursue justice further in King’s Bench. But Willis had really sought to indict a society, not a court. Public alarm and confusion might gain him much.

On 26 June, advised by the threatened law officers, Maitland and his council agreed to the “amoval” of Judge Willis; a week later, Hagerman was named to fill the post. Public meetings and messages of condolence encouraged Willis to press his case in London. Trustees, including the Baldwins, John Galt*, and their wives, offered to care for Lady Mary and the family, and Robert Baldwin undertook to act as her solicitor. But committees can only do so much, and when Lady Mary was to rejoin her husband in England, she quietly chose instead to take up residence in Montreal with an officer in the 38th Light Infantry, Lieutenant Bernard, and subsequently to elope to England, leaving her son in a maid’s care.

John Willis’ career and Upper Canada’s fortunes might have improved from that moment. Willis, as a cause, had helped to knit together the Reformers, who in the election of 1828 won their first assembly majority and elected Bidwell as speaker. Willis appealed his removal, lost an initial round, but was rehabilitated by the Privy Council, which overruled his amoval without chance of defence; he was given a new judicial appointment in Demerara (now part of Guyana). His marriage was dissolved, and in 1836 he married Ann Susanna Kent of Wick-Episcopi, Worcestershire, by whom he had three children. In 1841 he received another judicial appointment, in New South Wales, but again he clashed with a strong-minded governor, Sir George Gipps, and was amoved without notice; again, the Privy Council sustained his appeal on the same technicality. This time he received no new appointment. He retired to Wick House and lived privately for another 30 years.

In retirement Willis composed a summary of his colonial experiences, On the government of the British colonies. In it he displayed all that lack of faith in the colonies that had been implicit in his public career. Colonies, he argued like John Graves Simcoe*, only deserved recognition equivalent to English counties; as their highest political ambition they might be represented in the British parliament, but they should be administered by lords lieutenant. Whatever the convenience of the Willis incident to the Reformers of 1828, those future advocates of responsible government could not have lived with Willis for long – nor could most people.

J. W. Willis was the author of the following works A digest of the rules and practice as to interrogatories for the examination of witnesses, in courts of equity and common law, with precedents (London, 1816); Pleadings in equity, illustrative of Lord Redesdale’s treatise on the pleadings in suits, in the Court of Chancery, by English bill (London, 1820–21); A practical treatise on the duties and responsibilities of trustees (London, 1827).

PRO, CO 42/381–42/387; 42/408. G.B., Parl., House of Commons, Hansard, XXIV (1830), 551–55; Parl., House of Commons paper, 1831–32, XXXII, 740, pp.49–58, Upper Canada. Return to several addresses to his majesty, dated 31 July 1832 . . . ; Parl., House of Lords, The mirror of parliament . . . for the session . . . commencing 29th January 1828 . . . , ed. J. H. Barrow (36v., London, 1827–37), III, 1610–11, 14 May 1829. Papers relating to the removal of the Honourable John Walpole Willis from the office of one of his majesty’s judges of the Court of King’s Bench of Upper Canada ([London?], 1829). Upper Canada, House of Assembly, Journals, 1829, app., “Report of the select committee on the case of Mr. Justice Willis and the administration of justice.” “Willis v. Gipps [1846],” Reports of cases heard and determined by the Judicial Committee and the lords of the Privy Council, 1845–47, ed. E. F. Moore, V (The English Reports, XIII, Edinburgh and London, 1901, 379–91). DNB. “Willis-Bund of Wick Episcopi,” in Bernard Burke, A genealogical and heraldic history of the landed gentry of Great Britain (12th ed., London, 1914), 270–71. Craig, Upper Canada. Dent, Upper Canadian rebellion, I, 162–94. Aileen Dunham, Political unrest in Upper Canada, 1815–1836 (London, 1927),110–15, 157. William Kingsford, History of Canada (10v., Toronto, 1887–98), IX, 258–79. Roger Therry, Reminiscences of thirty years’ residence in New South Wales and Victoria . . . (2nd ed., London, 1863), 341–45. G. E. Wilson, The life of Robert Baldwin; a study in the struggle for responsible government (Toronto, 1933).

Cite This Article

Alan Wilson, “WILLIS, JOHN WALPOLE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/willis_john_walpole_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/willis_john_walpole_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alan Wilson |

| Title of Article: | WILLIS, JOHN WALPOLE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |