Source: Link

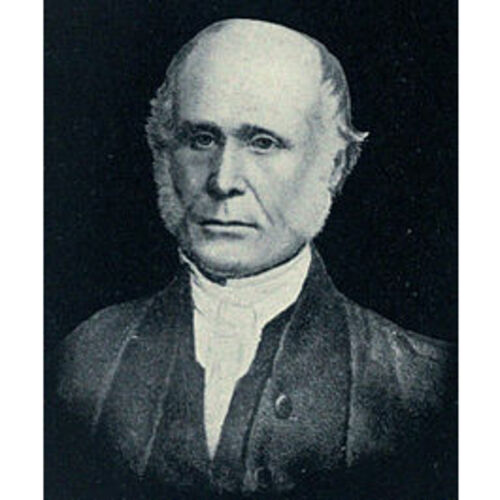

MACAULAY, Sir JAMES BUCHANAN, army and militia officer, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 3 Dec. 1793 in Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake), Upper Canada, second son of James Macaulay* and Elizabeth Tuck Hayter; m. 1 Dec. 1821 Rachel Crookshank Gamble in York (Toronto), and they had one son and four daughters; d. 26 Nov. 1859 in Toronto.

James Buchanan Macaulay was born in the fledgling loyalist settlement of Newark to parents recently arrived from England. His father, a British army surgeon, and his mother enjoyed the personal friendship of the province’s first lieutenant governor, John Graves Simcoe*, to which the given names of James’s older brother, John Simcoe Macaulay, bear eloquent witness. In 1795 or 1796 the Macaulays followed the seat of government to York near which the doctor had been granted a park lot. This land, stretching north into the edges of uncleared forest, rapidly attained the tag of Macaulay Town and as York grew it became a considerable financial asset for the Macaulay family.

In 1805 James was sent off to join other sons of Upper Canadian professional men in the privileged coterie of the Reverend John Strachan*’s school at Cornwall; there he undoubtedly rubbed shoulders with a fair number of his colleagues in later public life, including three future judges: John Beverley Robinson*, Archibald McLean*, and Jonas Jones*. On 14 Dec. 1809, a few days after his 16th birthday, Macaulay was commissioned an ensign with the 98th Foot, then stationed at Quebec. Appointed lieutenant in the Canadian Fencibles during the winter of 1812, that June, as rumours of war with the United States grew stronger, he became a lieutenant and acted as adjutant in the provincially raised Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles. Almost immediately he was thrown into battle, first on 19 July at Sackets Harbor, N.Y., where he was wounded in the left hip, and then in February 1813 at the battle of Ogdensburg, N.Y., where he led a gallant, if not entirely sensible, charge across the frozen St Lawrence into American artillery fire. For this action he received the commendation of his commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel George Richard John Macdonell*, and of Lieutenant-Colonel John Harvey, deputy adjutant general of the Upper Canadian forces. Briefly in command of the garrison at York in June 1814, Macaulay again fought courageously at Lundy’s Lane and Fort Erie later that summer. His military career had little future at the end of the war, however, and when his regiment was disbanded in the summer of 1816, he appears curiously enough even to have flirted with the notion of joining the new military settlement at Perth, Upper Canada, as a pioneer farmer. Instead he turned to that eminently attractive profession in the young province – law.

Macaulay entered his name on the books of the Law Society of Upper Canada in 1816, when he was 22, and began studying in the law office of Attorney General D’Arcy Boulton*. He was soon involved in the litigation following the incident at Seven Oaks (Winnipeg) in June 1816 [see Cuthbert Grant] and prepared charges for the trials of 1817–18, which were held, coincidentally, before Boulton, who had recently been appointed one of the assize judges. Continuing his studies with Boulton’s son Henry John Boulton*, Macaulay became an attorney-at-law in 1819 and served briefly in the office of John Beverley Robinson, who had succeeded the elder Boulton as attorney general. By the beginning of 1822 Macaulay had been called to the bar and had married a daughter of the late John Gamble, one of his father’s medical-military colleagues. Three years later he was admitted to the professionally desirable ranks of the Law Society benchers.

Macaulay’s industrious advocacy at the bar, revealed in the official law reports, and his impeccable social standing brought him to Sir Peregrine Maitland’s attention as an obviously desirable addition to the province’s ruling élite. On 5 May 1825 he was appointed to the Executive Council, an undoubted bastion of the “family compact,” where he joined Chief Justice William Campbell*, James Baby*, and John Strachan. His executive role was to be short-lived for his last appearance in council was on 2 July 1829. The intervening years were not exactly smooth for Macaulay but he weathered them with expected ease. As an executive councillor he had inevitably to suffer William Lyon Mackenzie*’s attacks in the Colonial Advocate, culminating in one on 18 May 1826 which described him as “a stink-trap of government.” That attack had not been entirely unprovoked for earlier in the month Macaulay had issued a pamphlet (of which no copies survive) uncharacteristically replying in kind to Mackenzie’s sniping. The next month, just prior to his official swearing-in as an executive councillor on 27 June 1826, Macaulay acted for Samuel Peters Jarvis, Henry Sherwood, and other young bloods from local society families whom he had seen toss Mackenzie’s type into the harbour on the evening of 8 June. At their trial that October a jury found in favour of Mackenzie and shortly thereafter Macaulay paid to Mackenzie’s lawyer the costs and damages assessed against his clients.

Macaulay was also party to the celebrated decision which removed Judge John Walpole Willis* from the Court of King’s Bench in 1828. During the long acrimonious dispute over his dismissal, Willis characterized Macaulay as “a Lieutenant on half pay, who ceased to be a Judge in consequence of my appointment.” In fact, when Judge Boulton had retired in 1827 prior to Willis’s arrival in Upper Canada, Macaulay had been temporarily appointed puisne judge to officiate during the summer assizes and had returned to his law practice that September when his commission had ended. This experience made him “a most eligible” candidate to replace Willis the following year, but since Macaulay had recommended in council “the measure which had occasioned the vacancy,” the appointment went instead to his brother-in-law, Christopher Alexander Hagerman*. Hagerman’s appointment was not confirmed, however, and in July 1829 Macaulay was elevated to Willis’s seat on the bench. That August he withdrew from the Executive Council in order to confine himself as much as possible “to duties exclusively Judicial.”

During the previous three years, Macaulay had collected several of the commissions necessary for the discharge of justice. As one of the three King’s Bench judges, he became enveloped in the sheer quantity of work both at sittings at York and on circuit when travelling conditions and weather permitted. Along with Chief Justice John Beverley Robinson, he presided over a welter of cases dealing principally, in the absence of a court of equity, with matters of civil litigation. Macaulay’s judgements on the many cases before him in the 1830s cannot be easily categorized but the law reports reveal the majority to be fair if cautious and rather more sensitive to social considerations than those of his fellow judges. He tended to clemency in cases of murder, though he rarely advised it directly. Most apparent from extant reports is his painstaking analysis of a case and the almost extreme lengths he would go to in order to be seen to be fair. His rulings and later recommendations on Orange rioters in the Johnstown District in 1833 [see Ogle Robert Gowan*] and on the murder trial of John Rooney and James Owen McCarthy* at Hamilton in 1834 nicely demonstrate Macaulay’s good sense and his understanding of human failings. A deep-seated concern for the orderly regulation of justice and for prison conditions is evident in his advocacy of provincial supervision of district jails during a charge to the grand jury at the Gore District Assizes on 17 Aug. 1835. With liberal sensibility Macaulay advised that “the Law is neither in a sealed book nor a dead letter” – a statement that might easily be hung as a label upon his legal career.

In 1838 Lieutenant Governor Sir Francis Bond Head*, writing to his successor, Sir George Arthur, highly recommended Macaulay as “most excellent – man & lawyer.” More than 20 years later the writer of his obituary would note that “whether . . . as a soldier, a lawyer, a judge, or . . . a Christian, . . . in all his actions” can be traced “the same entire devotion to the calls of duty.” As a devout Anglican and a warden of St James’ Church for most of his adult life, Macaulay dealt with all sorts of parochial affairs including provision for poor relief. As a former army officer and militia colonel, he had directed the militia in the defence of Toronto during William Lyon Mackenzie’s uprising in December 1837. As a provincial judge with a capacity for hard work and a reputation for clear thinking, he was asked by Lieutenant Governor Arthur in 1839 to complete an investigation of the Indian Department begun by the provincial secretary, Richard Alexander Tucker*.

During March and April of that year Macaulay, though professing uncertain health and overwork, rushed off a lengthy report on the economic and social plight of what he termed “the degenerate races.” This long-winded survey (some 446 manuscript pages) reveals concern and indicts some past practices, but it offered very little for future improvements in handling Indian problems and appears to rely on an extension of “Christian charity” to cope with the “far greater numbers of destitute tribes” that “inhabit the remote regions of the North,” beyond lakes Huron and Superior and certainly beyond the experience or knowledge of James Buchanan Macaulay. The hurried examination was well enough received, however, for he was appointed with Robert Sympson Jameson and William Hepburn to a more formal examination of the Indian Department as part of the general investigation of provincial administration in 1839–40. Simultaneously he served as chairman of the committee investigating the workings of the Executive Council. Though Macaulay’s insight into public affairs is not revealed in these departmental reports, Governor Lord Sydenham [Thomson*], who had known him only for a short time, had no compunction in recording early in 1841 that “in political matters I know of no one whose opinions I would rather consult for I esteem him highly.”

Nevertheless, it was to judicial matters that Macaulay turned for the remainder of his life. Along with commissioners John Beverley Robinson, William Henry Draper*, and John Hillyard Cameron*, he embarked on the first revision of Upper Canadian statute law in 1840 and served on the commissions of 1842 and 1843 inquiring into the Court of Chancery. In 1843 he was appointed to the Court of Appeal and in 1849 he was clearly the most logical and desirable choice for the position of chief justice in the reconstituted Court of Common Pleas. Macaulay held this post until the pressure of unremitting daily work on and for the bench, together with a self-admitted hearing loss, forced him to retire in 1856. That April he received the title of Queen’s Counsel and the following January he agreed to supervise yet another statute revision committee, this time for both Upper and Lower Canada. Fellow commissioner David Breakenridge Read* lauded Macaulay for his amazing attention to details of law and of language and for his refusal to accept any remuneration over and above his pension though he served as chairman for nearly two years. Despite Macaulay’s failing health, another judgeship followed in the summer of 1857, a seat in the Court of Error and Appeal. The next year he was made a cb and on 13 Jan. 1859 he was knighted. That February the Law Society of Upper Canada, which Macaulay had shepherded and served for more than 35 years, conferred on him the office of treasurer, succeeding the late Robert Baldwin. Quite fittingly, perhaps, in retrospect, it was at Osgoode Hall on the morning of his re-election to this position that his heart failed.

James Buchanan Macaulay ended his days in what the young attorney general, John A. Macdonald*, paying tribute to him at a retirement dinner in 1856, had called “an untiring assiduity.” The Upper Canada Law Journal that year noted the “ample monuments” represented by Macaulay’s judgements in the law reports and observed quite accurately that he was the sort of figure whom “men of all parties looked up to as a pattern of judicial purity.” He had, in short, as that journal recorded at his death, quite simply “grown with the country.” A shy, retiring man, hesitant in speech but fluent and eminently rational in his reports, charges, and judgements, Macaulay had developed vast experience in watching over and guiding the new society. His opinions and recommendations were sought on a wide range of issues affecting the machinery of government, his citizenship and private life were exemplary, and his military youth suitably dashing. To his equally reticent wife, who survived him until 1883 when she died in England at the home of a married daughter, Macaulay left the family home in Toronto, Wykeham Lodge, and an estate worth $40,000. To the province he left a legacy of quiet public service and principled professionalism.

A portrait of James Buchanan Macaulay in the robes of chief justice of the Common Pleas, c. 1854, artist unknown, hangs in the Law Society of Upper Canada’s premises at Osgoode Hall, Toronto.

AO, MS 35; MS 78; MU 2197; RG 22, ser.305, J. B. Macaulay. Law Soc. of U.C. (Toronto), “Journal of proceedings of the Convocation of Benchers of the Law Society of Upper Canada” (8v.), I: 93; III: 516–21; Secretary’s notes: 145. PAC, MG 29, D61: 5088–89; RG 1, E1, 52: 239–40, 529; 53: 220; 79: 128; RG 8, I (C ser.), 30: 8, 114; 220: 200; 228: 53; 678: 98–102; 682: 86; 1168: 177; 1170: 107–8; 1706: 62–63; RG 10, A6, 718–19; RG 68, General index, 1651–1841; 1841–67. PRO, CO 42/375: 85–86; 42/381: 34–35; 42/384: 110–13; 42/388: 55–60; 42/389: 124–31, 150–51; 42/390: 414; 42/423: 95–112; 42/427: 249–58. Arthur papers (Sanderson). “The Honourable James Buchanan Macaulay,” Upper Canada Law Journal (Barrie, [Ont.]), 2 (1856): 38–39. “Sir James Buchanan Macaulay,” Upper Canada Law Journal (Toronto), 5 (1859): 265–68. Town of York, 1815–34 (Firth). U.C., Commission appointed to inquire into and investigate the several departments of the public service, Report (Toronto, [1840]). Colonial Advocate, April–May 1826. Globe, 28, 30 Nov. 1859. Sarnia Observer, and Lambton Advertiser, 2 Dec. 1859. DNB. D. B. Read, The lives of the judges of Upper Canada and Ontario, from 1791 to the present time (Toronto, 1888). W. R. Riddell, The legal profession in Upper Canada in its early periods (Toronto, 1916). Scadding, Toronto of old (1873).

Cite This Article

Gordon Dodds, “MACAULAY, Sir JAMES BUCHANAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macaulay_james_buchanan_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macaulay_james_buchanan_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gordon Dodds |

| Title of Article: | MACAULAY, Sir JAMES BUCHANAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |