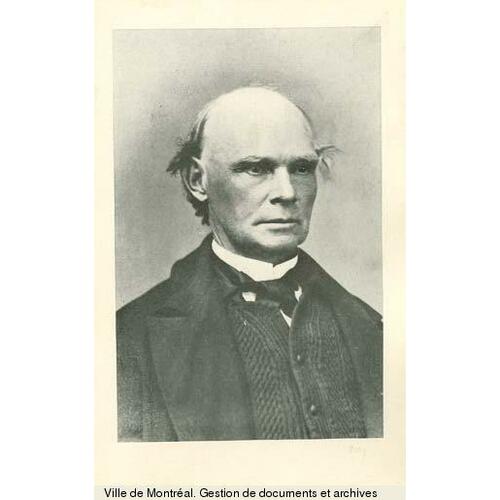

DAY, CHARLES DEWEY, lawyer, politician, judge, and educationalist; b. 6 May 1806 in Bennington, Vt, son of Ithmar Hubbell Day and Laura Dewey; m. first in 1830 Barbara Lyon, and they had three children; m. secondly in 1853 Maria Margaret, daughter of Benjamin Holmes*; d. 31 Jan. 1884 while visiting England.

Charles Dewey Day’s father, “Capitain” Ithmar Day, probably worked with the North West Company before moving his family from Vermont to Montreal in 1812 to begin a retail business in drugs and provisions. Some time after 1828 he moved to Hull where he established a sawmill, fulling-mill, and blacksmith shop. His eldest son, Charles Dewey, was educated in Montreal and, after studying law for five years under Samuel Gale*, was admitted to the Lower Canadian bar on 25 May 1827. Although Day maintained offices in Montreal, he was most active in the Ottawa valley where he acted as counsel for such timber barons as Ruggles and Philemon Wright*. On 4 Jan. 1838 Day was appointed qc.

Day’s growing political prominence may explain his rapid professional advancement. He had begun his political career in April 1834 by publicly protesting the House of Assembly’s endorsement of Louis-Joseph Papineau*’s 92 Resolutions. Papineau’s opponents soon formed constitutional associations and Day became a prominent spokesman in the one at Montreal. At the Montreal Constitutionalists’ initial meeting Day was not only placed on the committee of correspondence, but was chosen to second Augustin Cuvillier*’s resolution endorsing “the continuance of the existing connection between the United Kingdom and this Province.” The commercial bias of Day’s political philosophy is clearly revealed in the speech he gave on this occasion. After condemning the “band of mad revolutionalists” desirous of starting a Canadian civil war, he adamantly defended the continuance of British immigration to Canada and the reputation of the British American Land Company, which the Patriotes had attacked. Subsequently he was among those who favoured the abolition of feudal tenure, equal sharing of the clergy reserves among Protestant denominations, and the establishment of an office of land registry. In 1836 he won a closely contested election to serve as a delegate to a convention called to petition the king and parliament on the state of politics in Lower Canada.

The outbreak of rebellion accelerated Day’s political ascendancy. In 1838 he was appointed deputy judge advocate to preside over the trials of Patriote prisoners, and in May 1840 he entered the appointed Special Council as solicitor general, taking the place of the late Andrew Stuart*. Given Day’s long-standing commitment to a legislative union of Upper and Lower Canada, it is not surprising that Governor General Lord Sydenham [Thomson*] invited Day to continue as solicitor general in the Executive Council constituted to carry union. In the subsequent general election held early in 1841 Day successfully contested the Ottawa constituency, a contest which cost his election committee, composed of timber men like Ruggles Wright, some £1,580. But Day’s Tory past proved obnoxious to the Reform members of Sydenham’s coalition cabinet and in February 1841 Robert Baldwin* demanded Day’s resignation as a condition of his group’s support of Sydenham’s government. In the end Baldwin, not Day, left the cabinet. Yet Day’s victory proved short-lived. On 28 June 1842 Governor General Sir Charles Bagot*, in an effort to make his Executive Council more representative of the will of the lower house, named Day to the Court of Queen’s Bench.

Out of office, Day’s differences with the Reform party were soon resolved. On 1 Jan. 1850 he was raised to puisne judge of the Superior Court by the Reform government of Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* and in the mid 1850s he became a strong supporter of the prominent Liberal, John Young*, and of his schemes to improve transportation facilities on Lac Saint-Pierre. As a judge, one of Day’s most exacting tasks was to help untangle the complex claims created by the abolition of seigneurial tenure in 1854 [see Lewis Thomas Drummond]. In 1859 the Conservative government of George-Étienne Cartier* and John A. Macdonald* named Day to the commission to codify the civil law of Lower Canada, a task which he shared with Augustin-Norbert Morin* and René-Édouard Caron* and which occupied the next six years of his life. Accepting particular responsibility for drafting sections of the code relating to commercial matters, Day accomplished for the commission what probably constitutes his most significant legal contribution. In 1865 he was appointed to a commission to determine the amount of government subsidy to be paid railway companies carrying the provincial post, and in that same year became the Hudson’s Bay Company’s attorney in a lengthy case in which the company pressed claims against the United States government arising out of the Oregon treaties of 1846 and 1863. Meanwhile, in 1868 Day became the province of Quebec’s arbitrator to divide and adjust “the credits, liabilities, properties and assets” resulting from the former union of the two Canadas. Finally in 1873 John A. Macdonald appointed Day to the royal commission to report on Lucius Seth Huntington’s charges of corruption against the Conservative government for its handling of the proposed Canadian Pacific Railway charter.

Apart from law and politics, Day’s principal interest was education. In 1836 he had joined the executive of a small Montreal committee to improve provincial education, which counted among its members many who would become Patriote leaders. In 1841, as solicitor general, he introduced a bill to establish and maintain government-assisted common schools in the united province along the lines first suggested in the Durham Report. One of the original incorporators of the Advocates’ Library and Law Institute of Montreal, he served as its president in 1847–48. He also helped organize the Montreal meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in August 1859. In 1869 Day was named to the Quebec Council of Public Instruction and served as chairman of its Protestant committee from 1869 to 1875; in the following year he was reappointed to the reconstituted council. Even his tenure as vice-president of the Anglican Church Society from 1842 to 1852 may have been motivated by that society’s educational objectives.

But Day’s most important educational work was with the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning, the provincial body responsible for higher education. A member of the institution’s board of governors, he served as its president from 1852 to 1884, and as principal pro tempore of McGill College from 1853 to 1855 and chancellor of the university from 1864 to 1884. With Christopher Dunkin he engrafted the faculty of law onto McGill in 1848, and affiliated to it as well the High School of Montreal, the McGill Normal School (Montreal), St Francis College (Richmond), and Morrin College (Quebec). It was Day, too, who in 1852 insisted on amending the Royal Institution’s statutes, thereby ending the old antagonism between it and McGill College’s directors [see John Bethune*]. Day pressed for the inclusion of science and modern literature in the curriculum and was responsible for the selection in 1855 of McGill’s most distinguished principal, John William Dawson*, who established the university’s academic reputation. Not only was Day the architect of McGill’s mid-century revival, but he also guided it through numerous legal and political difficulties. At his death in 1884 the university’s board of governors declared that McGill’s “progress and present prosperity in a great measure are due to his eminent ability and wise counsel.”

ANQ-M, État civil, Presbytériens, St Andrew’s Church (Montreal), 1830–36; Unitariens, Messiah Unitarian Church (Montreal), 1853; Minutiers, G. D. Arnoldi, 1828–36. McGill Univ. Arch., Minutes of the board of governors, 1848–84. PAC, MG 24, D8. The Arthur papers; being the Canadian papers mainly confidential, private, and demi-official of Sir George Arthur, K.C.H., last lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, in the manuscript collection of the Toronto Public Libraries, ed. C. R. Sanderson (3v., Toronto, 1957–59). Can., Prov. of, Legislative Assembly, Journals, 1841–45. Church of England, Church Soc. of the Diocese of Quebec, Annual report (Quebec), 1843–52. [C. E. P. Thomson], Letters from Lord Sydenham, governor general of Canada, 1839–1841, to Lord John Russell, ed. Paul Knapland (London, 1931). Bytown Gazette [Ottawa], February 1836–September 1837. Canadian Courant and Montreal Advertiser, 13 Aug. 1814–15 April 1816. Gazette (Montreal), January–May 1834, April–July 1836, January–March 1884. An alphabetical list of the merchants, traders, and housekeepers, residing in Montreal; to which is prefixed, a descriptive sketch of the town, comp. Thomas Doige (Montreal, 1819). F.-J. Audet, “Commissions d’avocats de la province de Québec, 1765 à 1849,” BRH, 39 (1933): 584. Canada, an encyclopædia (Hopkins). [G. E. Day], A genealogical register of the descendants in the male line of Robert Day . . . (2nd ed., Northampton, Mass., 1848). J. Desjardins, Guide parl. Montreal directory, 1842–59. Notman and Taylor, Portraits of British Americans. Political appointments, 1841–65 (J.-O. Coté). P.-G. Roy, Les juges de la prov. de Québec. Atherton, Montreal, I–II. N. F. Davin, The Irishman in Canada (London and Toronto, 1877). Dent, Last forty years. R. S. Longley, Sir Francis Hincks; a study of Canadian politics, railways, and finance in the nineteenth century (Toronto, 1943). C. W. New, Lord Durham; a biography of John George Lambton, first Earl of Durham (Oxford, 1929). Rich, History of HBC, II. L.-P. Audet, “La surintendance de l’éducation et la loi scolaire de 1841,” Cahiers des Dix, 25 (1960): 147–69. J. E. C. Brierley, “Quebec’s civil law codification; viewed and reviewed,” McGill Law Journal (Montreal), 14 (1968): 521–89. Olivier Maurault, “Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine à travers ses lettres à Amable Berthelot,” Cahiers des Dix, 19 (1954): 129–60. Maréchal Nantel, “En marge d’un centenaire,” Cahiers des Dix, 17 (1952): 233–44.

Cite This Article

Carman Miller, “DAY, CHARLES DEWEY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/day_charles_dewey_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/day_charles_dewey_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carman Miller |

| Title of Article: | DAY, CHARLES DEWEY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |