Source: Link

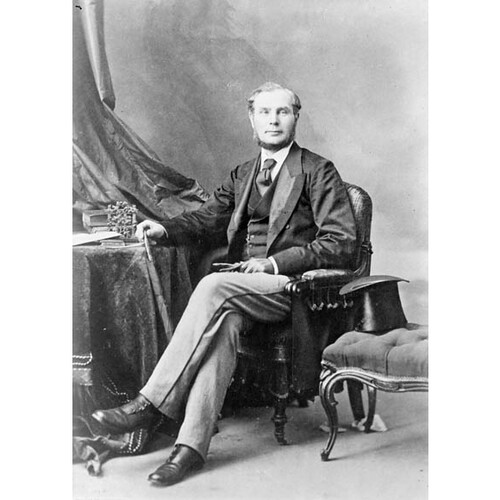

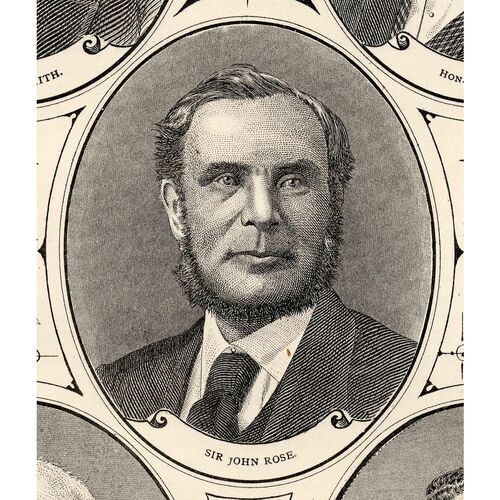

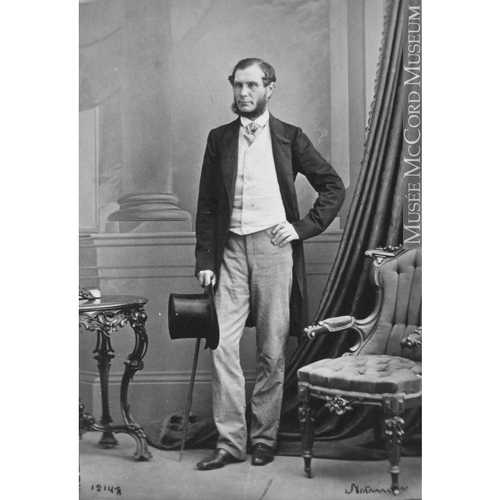

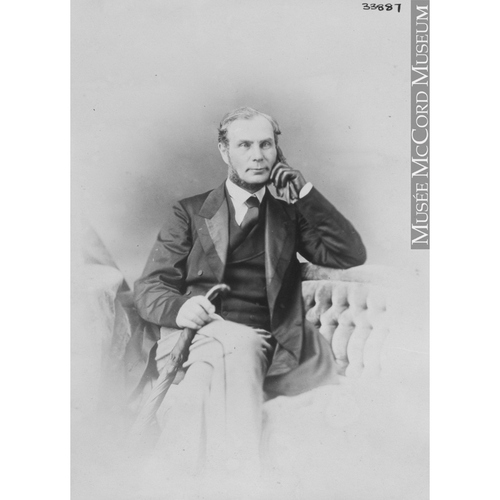

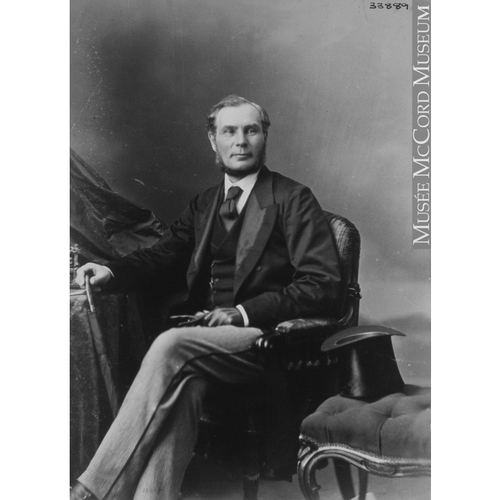

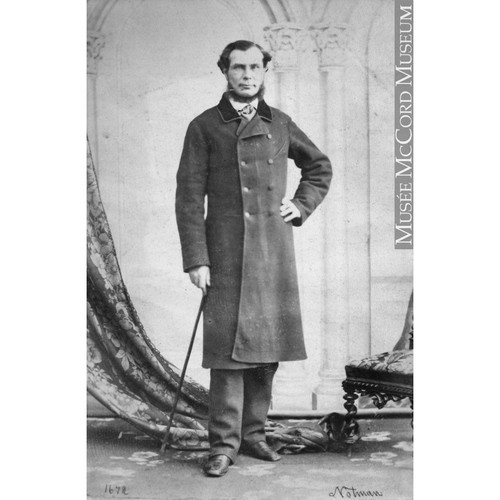

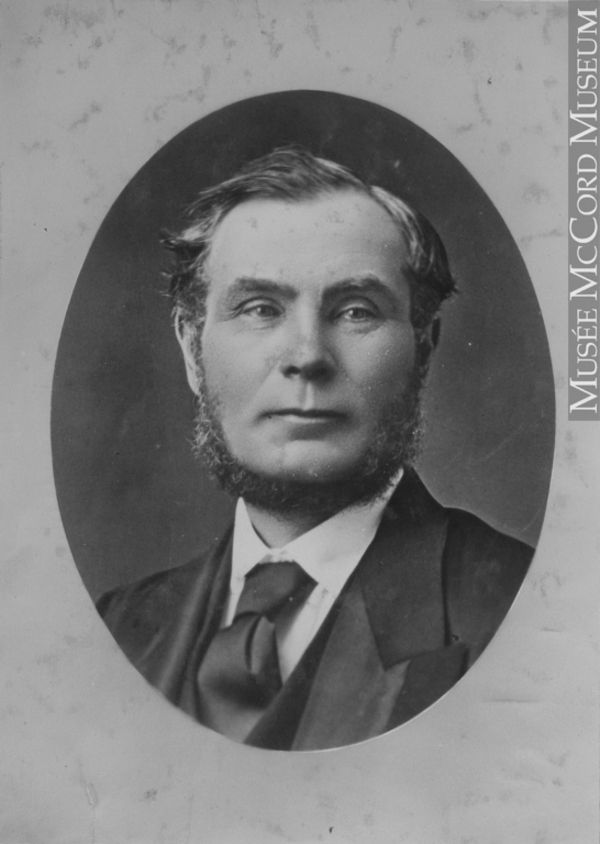

ROSE, Sir JOHN, lawyer, financier, politician, and diplomat; baptized 2 Aug. 1820 in Nether Ordley in the parish of Auchterless, Scotland, son of William Rose and Elizabeth Fyfe; d. 24 Aug. 1888 in Langwell Forest near Ord of Caithness (Highland), Scotland.

A prominent Montreal lawyer

Little is known about his parents but young John Rose was given a solid education at Udny Academy, a grammar school outside Aberdeen, and King’s College, one of the founding institutions of the University of Aberdeen. Rose’s entrance into university at 13 was not uncommon at the time; after one year of study in the arts course, however, he dropped out of King’s College. In 1836 he immigrated to Lower Canada with his parents, settling at Huntingdon, where he was a teacher for a brief period, before acting as tutor for the family of Colonel John By*. During the rebellions of 1837–38 he served as a volunteer and is believed to have assisted in recording court martial proceedings against captured Patriotes. He studied law in Montreal under Adam Thom and then under Charles Dewey Day, and was called to the bar in 1842.

Rose attached himself to the city’s rising mercantile and banking interests and soon built a thriving practice in commercial law. Among his partners were Samuel Cornwallis Monk, later a prominent jurist in Quebec, and Thomas Weston Ritchie. Rose served as legal adviser in Canada to Edward Ellice* and was closely identified with the operations of the Hudson’s Bay Company. His business associates included other members of the board of the Bank of Montreal, with a number of whom he signed the Annexation Manifesto in 1849. This step cost him the qc he had been given the year before, but he soon regained a respected position in Montreal life and was reinstated qc in 1853. In addition to his directorship of the Bank of Montreal, he served on the boards of the City Bank, the Montreal Telegraph Company, the Grand Trunk Railway, the New City Gas Company of Montreal, and the North British and Mercantile Insurance Company. He participated actively in such community enterprises as the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning, the Montreal Protestant House of Industry and Refuge, and the Mercantile Library Association. Intelligent, energetic, and personable, Rose was reputed to possess the largest law practice in Montreal by the early 1850s, his clients including leaders of the business community: Sir George Simpson*, Hugh Allan, George Stephen*, and others.

Early years in politics

Some ten years before, he had made the acquaintance of John A. Macdonald* and the two developed a close, lifelong friendship, Macdonald being five years older. Macdonald would later tell Lord Carnarvon that as young men he, Rose, and a third man had paid a carefree visit to the United States as strolling musicians. “Macdonald played some rude instrument, Rose enacted the part of a bear and danced. . . . To the great amusement of themselves and every one else, they collected pence by their performance in wayside taverns.” Their first collaboration in public affairs occurred in the summer of 1857 when Macdonald, as joint head of the Liberal-Conservative administration, asked Rose to accompany him to London to assist in obtaining financial support for the Intercolonial Railway from the British government. The ministry of Lord Palmerston refused to grant aid and the mission was unsuccessful.

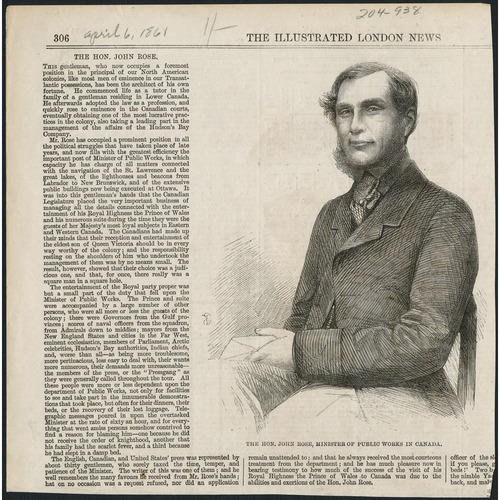

Nevertheless, Macdonald was sufficiently impressed with Rose’s legal and personal capabilities that he persuaded the Montreal lawyer to enter his ministry; although Rose had been importuned to enter public life since the early 1850s, he had decided not to commence a political career until he had acquired independent means. On 26 Nov. 1857 he was appointed solicitor general of Canada East and won a seat in Montreal in the ensuing general election. In the contest for the three-member riding Rose was the only ministerial candidate elected, George-Étienne Cartier* and Henry Starnes* going down to defeat. Rose was never as committed to politics and parties as Macdonald but he saw in government office a means of accomplishing important economic and national projects; in fact Rose was continually regarded with suspicion by members from Canada West as an agent of the HBC. During the “double shuffle” [see Cartier] in August 1858 he was receiver general for a day before resuming his post of solicitor general. On 11 Jan. 1859 he was appointed chief commissioner of public works, a post which brought him to the centre of the controversy regarding the construction of the new Parliament Buildings in Ottawa. Begun in 1860, the project was soon troubled by large over-expenditures as well as a lack of cooperation between the architects and the political and administrative heads of the Department of Public Works. Inevitably Rose’s role in the complicated dispute meant that he was criticized and on 12 June 1861, worn out by ill health and by the heavy demands of his public duties and a large professional practice, he resigned office. He kept his seat, however, and was re-elected in 1861 and 1863 for Montreal Centre.

A more satisfying achievement for him as commissioner of public works was the management of arrangements for the tour of British North America by the 19-year-old Prince of Wales in the summer of 1860, the first visit to North America by a direct heir to the British throne. Rose was responsible for coordinating the myriad details of transportation, communication, and accommodation for the progress of the substantial party of some 250 to 300 people across the Province of Canada. The administrative ability he revealed, as well as his poise in meeting unexpected situations such as the threat of trouble in Kingston [see John Hillyard Cameron*], were widely remarked upon. They laid the basis for the “lasting intimacy” which, according to a biographer of the future King Edward, was to grow up between Rose and the prince. In Montreal, where the party arrived in late August, the prince stayed in Rose’s large residence on Mount Royal, with its fine view of the city and river, before continuing on to the United States on 20 September.

Relations with the Hudson’s Bay Company

Rose did not take a prominent part in the confederation movement, although he was an unofficial delegate from the Protestant minority of Canada East at the London conference in 1866–67. His major public activity during these years was diplomatic, assisting in the settlement of HBC claims for losses incurred by the cession of lands to the United States in the Oregon Territory. The HBC had tried vainly to sell properties that it or its subsidiary, the Puget’s Sound Agricultural Company, had abandoned following the 1846 treaty. In 1857 the British government took up the company’s case, instructing its minister in Washington to discuss with the United States procedures to assess claims for compensation for property and privileges surrendered. The two countries eventually agreed on a joint commission on the model of those previously used for disputes over boundary and commercial claims. A treaty to this effect was signed in Washington in 1863 and Rose, who as counsel to the HBC in Canada had been involved in the question for years, was appointed the British commissioner in April 1864.

The United States appointed Alexander Smith Johnson, a judge of the federal Court of Appeals, as commissioner, an office was established in Washington, and the laborious task of assembling claims and evidence, from Oregon to England, began. It dragged on for three years, until May 1868, when arguments were presented to the commissioners. During this last phase Rose was engaged in discussions with the HBC and the British government to settle on a sum the company would be prepared to accept for its holdings. It was not until 10 Sept. 1869 that he and Johnson were able to announce a mutually acceptable award, granting $450,000 in gold to the HBC and $200,000 to its subsidiary. The Oregon claims settlement, although a minor contribution to Anglo-American accord, was an important experience for Rose. Through its proceedings he became acquainted with several American public men, most notably Caleb Cushing, the American counsel to the commission and a long-time adviser to the Department of State. These links were to be valuable to him in his larger diplomatic undertakings after 1869.

Minister of finance

The dominion’s currency

Rose had stood for election to the first dominion parliament in 1867, winning a seat for Huntingdon as a Conservative. He was a candidate for speaker of the House of Commons but had to withdraw in favour of James Cockburn when another Quebec representative, Joseph Cauchon, was chosen speaker of the Senate. Shortly afterwards he was unexpectedly brought into the Macdonald cabinet upon the resignation of Alexander Tilloch Galt* as minister of finance. Rose’s banking associations made him a natural choice and he was sworn in on 18 Nov. 1867.

His two-year occupancy of the finance portfolio was dominated by a great struggle over the nature of the dominion’s first banking system. At issue was whether the individual Canadian banks should continue to possess the right of free note issue, a profitable activity, or whether there should be a state currency backed by government securities. Rose, worried about recent bank failures in Ontario, favoured the latter plan. He adopted as a model the recent National Bank Act of the United States (1863), which had established a uniform note issue supported by government debentures. This plan was also advocated by the dynamic Edwin Henry King*, the cashier (general manager) of the Bank of Montreal. Much the largest bank in Canada, and perhaps in North America, the Bank of Montreal already possessed dominion securities and notes issued under Finance Minister Galt, which it could use to acquire federal notes. A state currency would oblige the smaller Ontario banks to commit their limited capital to the purchase of securities and they might even have to recall loans to do so. There was also the probability they would have to borrow from Montreal to meet the large cash requirements needed for “moving the crops” each autumn. While Rose preferred a bond-supported currency his proposal, moreover, weakened the branch banking system and encouraged small independent country banks, leaving the financing of major commerce and foreign trade to the large banks. It was clear that the Bank of Montreal, the Bank of British North America, and some institutions in the Maritime provinces would be in a position to carry out the latter function. Thus the issue was joined. The Canadian Bank of Commerce [see William McMaster], the Bank of Toronto, and other Ontario banks, together with banks in Quebec and Halifax, opposed the Rose plan. Their connections with the Liberal party ensured strong political opposition to legislation that Rose might introduce.

The battle raged through two sets of parliamentary hearings, one conducted by the Senate committee on banking, commerce, and railways, the other by the corresponding commons committee, which was chaired by Rose. The unhappiness with Rose’s scheme showed itself clearly in a meeting of Ontario bankers held in Ottawa in April 1868 and in the replies to a commons committee questionnaire, which were largely hostile to state issue of notes. Nevertheless Rose embodied his plan in resolutions he presented to parliament on 14 May 1869; one day of debate, 1 June, confirmed the strength of the opposition. Macdonald’s cabinet was itself divided on the issue and the prime minister wisely decided to withdraw the measure. The struggle has been interpreted as one between Montreal, seeking to maintain its position as the country’s financial centre, and the rising commercial and financial aspirations of Toronto. Rose, always closely identified with Montreal’s interests, felt discredited by the rebuff to his legislation. It led directly to his decision, effective in September, to resign his portfolio, leave Canada, and enter the world of international finance.

Other issues

As finance minister Rose had to supervise the consolidation of the public accounts of the various jurisdictions comprising the new federation. He also undertook the task of assimilating the separate tariffs and revenue duties of the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. His first major budget speech was delivered on 7 May 1869 and showed a conservative approach to the management of expenditures and the growth of the public debt. He established the rule, for instance, that unused appropriations lapsed at the end of each fiscal year. In July 1868 he journeyed to England to place a loan of £2,000,000 for the Intercolonial Railway (his temporary use of the proceeds of this loan, raised partly under an imperial guarantee, occasioned an important constitutional dispute with the British Treasury), and in January 1869 he carried out negotiations with Archibald Woodbury McLelan and Joseph Howe* for “better [financial] terms” for Nova Scotia.

Rose also entered into discussions with the United States concerning issues unsettled since the abrogation of the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854. His discussions with Hamilton Fish, President Ulysses S. Grant’s secretary of state, held in Washington from 8 to 11 July 1869, covered the temporary use of Canadian inshore waters by American fishermen, the free navigation of the St Lawrence River, the enlargement of the Canadian canals, and the assimilation of customs and excise duties with the United States. Rose was also prepared to offer free trade in certain manufactured products, as well as in natural goods, to the United States. This concession was publicly denied after he had left office by his successor, Sir Francis Hincks, and by Prime Minister Macdonald. Given the strong anti-British North American sentiment in Congress after the Civil War, Rose’s projet of a treaty was abortive.

Anglo-American relations

Rose’s conversations with Fish also touched on this larger problem of the unsatisfactory state of Anglo-American relations resulting from the unsettled issues of the American Civil War. Foremost among the differences was the American desire for compensation under the “Alabama claims,” an issue that Senator Charles Sumner, in an electrifying speech in April 1869, had linked to the cession of Canada to the United States. Rose and Fish discussed the state of opinion about Sumner’s demand and considered possible means of adjusting Anglo-American differences. Rose indicated that his impending departure for a private business career in England offered an opportunity for him to be of service in this area.

Although Rose took up residence in London in the autumn of 1869 the opportunity to assist in improving Anglo-American relations did not arise until November 1870, when the British government of William Ewart Gladstone accepted a Foreign Office plan to establish a joint high commission charged with devising a mechanism for settling outstanding issues between the countries. In a memorandum to the foreign secretary, Lord Granville, on 26 November, Rose proposed that the American government might be sounded out on the plan through “some intermediate agency in no way responsible or accredited, but yet possessing in sufficient measure the good-will of each.” Shortly afterwards he was asked to undertake the “agency,” in the capacity of “a private person engaged in commercial transactions” with the United States. Essentially his task was to question, listen, and report back to London. The importance of his mission was underlined by the fact that his instructions were “shown to the Queen, Mr. Gladstone and the cabinet” and the expenses of his trip were borne by the British government.

Rose arrived in Washington on 9 Jan. 1871. There he remained for the next three weeks, conducting conversations with Fish, other members of the Grant administration, and leading senators. Early on, Rose confirmed the assertion of the British minister in Washington, Sir Edward Thornton, that there could be no cession of Canada in compensation for the Alabama claims, nor would Britain admit unqualified liability for the actions of Confederate cruisers. Liability would have to be determined by arbitration based on mutually acceptable rules for the conduct of a neutral state. The discussions, long and involved, were carried out against the knowledge that the formidable Senator Sumner might at any time play the role of “spoiler.” When Rose met him at a dinner party on 20 January he was baited by the senator: “Haul down that flag and all will be right.”

Financial interests and diplomacy

Giving substance to the exchanges was the reality of massive economic and financial benefits to be realized from an Anglo-American settlement. Business and transportation interests on both sides of the Atlantic were pressing for an accommodation while the United States’ plan of re-funding the Civil War debt depended upon substantial European support for a new bond issue. Rose was only too well aware of these considerations through his association with European and American banking groups. Arrangements for the formation of a joint high commission to review Anglo-American differences, and their effects on Canada, were accepted by the time Rose left Washington for Ottawa on 2 February.

Rose’s place in the negotiations was emphasized when Lord Granville proposed his appointment to the joint high commission. Both Sir Edward Thornton and Fish were favourable, but the suggestion was not acceptable to the Canadian cabinet. Macdonald and his colleagues felt that since Rose had severed his formal ties with Canada and held a pecuniary interest in the prospect of transatlantic friendship, he would not be a suitable person to represent Canada’s interests. Governor General Lisgar [Young*] distrusted Rose, believing, in spite of Thornton’s denials, that Rose had been negotiating with the Americans over the fisheries without Ottawa’s approval. The alternative Granville had proposed was Macdonald, who clearly stood in a better position to have an eventual treaty accepted in Canada. Rose accepted the decision with his customary urbanity and returned to London.

This informal mission in 1871 marked the high point in Rose’s diplomatic career. His achievement had been grounded on the crucial fact that he was persona grata in influential circles on both sides of the Atlantic. But Rose’s individual qualities also contributed to the success of his efforts. “A natural diplomat of a high order,” Lord Granville called him; “a man of tact and discretion,” “moderate and fair,” observed Thornton. Yet if Rose’s activity as an expediter must be praised, it should be noted that his discussions with Fish failed to clarify all the points of disagreement between the parties. For example, he did not press Fish on whether the “indirect claims” resulting from the Alabama depredations would continue to be asserted by the United States in the future arbitration. When they were brought forward in further negotiations at Geneva in 1872 the action almost destroyed the arbitration and the entire settlement. Yet the stakes in the restoration of favourable Anglo-American relations were high and ambiguity is often the truest wisdom in diplomacy.

A merchant banker in London

Rose had moved to London in the midst of the effort to meet the needs of North American economic development through the creation of transatlantic partnerships in banking and finance. The utility of these connections was readily apparent. There were American government securities to be sold in Europe, as well as innumerable exchange transactions arising from the revival of commerce with the United States following the Civil War and intensified by the postwar boom in railway building. Rose took over the London office, established in 1863, of the American firm of Morton, Bliss and Company; this major American banking house, operated by Rose’s personal friend Levi Parsons Morton and his partner George Bliss, was noted for its involvement in railway interests. Rose was able to assume the position when Walter Burns, the man in charge, was obliged to withdraw from the firm after marrying the daughter of a competitor, John Pierpont Morgan. Typically, the London firm, styled Morton, Rose and Company after the arrival of the new partner in 1869, was not a branch office but a partnership, a separate legal entity that secured its own business, maintained a separate capital account, and simply cooperated with the American firm. Rose managed the London operation until he stepped down in favour of his second son, Charles Day, in 1876. But the elder Rose remained an active figure on the London financial scene, continuing his influence with his old firm until his unexpected death in 1888. He was a member of the London committee of the Bank of Montreal, a director of the Bank of British Columbia, and the deputy governor of the HBC from 1880 to 1883, and he also had associations with several British banks and insurance companies.

Morton, Rose and Company stood in a strategic position to facilitate the growing volume of public and private investments across the Atlantic. Through Levi Morton it acted as a fiscal agent for the United States government from 1873 to 1884 and participated in the European phase of the re-funding of the American national debt. Through John Rose the company shared many important financial transactions with the Canadian government’s principal financial agents in London, Baring Brothers and Company and Glyn, Mills, Currie and Company. It also handled offerings for the province of Quebec and the city of Montreal. It derived the normal commissions from the flotation and renewal of these public borrowings and also profited from Canadian government purchasing in London. These operations were undoubtedly lucrative for Morton, Rose and Company and for Sir John.

The most active field for Morton, Rose and Company was in railway financing. Here Rose’s association with the Macdonald government was of vital significance. As a personal friend of both Macdonald and George Stephen he assisted in the negotiations that led to the creation in Ottawa on 21 Oct. 1880 of the original Canadian Pacific Railway syndicate, which included his firm, Morton, Rose and Company; the latter was also represented on the CPR board. The syndicate, with Rose’s help, succeeded in attracting Morton, Bliss and Company, as well as other American banks, to aid in the substantial task of raising funds for the transcontinental line. Rose vigorously defended the CPR in London against the attacks of its rival, the Grand Trunk, lobbied for a Pacific steamship service contract for the company, and sought to coordinate land sales between the railway and the HBC, of which he was deputy governor. In 1882 Rose, accompanied by Sir Robert George Wyndham Herbert, permanent undersecretary at the Colonial Office, paid a visit to the Canadian northwest to examine CPR construction and the progress of settlement. Although his personal loyalty to the CPR could not be questioned, that of Morton, Rose and Company was later to be. This occurred well after the management of the firm had passed to his son, whom George Stephen believed to be sympathetic to the Grand Trunk. Desiring more vigorous representation in London, Stephen persuaded Barings to take on a CPR mortgage bond issue in 1885. Thereafter the firm’s relationship with the railway was not as intimate.

Canada’s unofficial representative in London

But Rose in London was always more than a financier. In a functional sense he acted as a quasi-official representative for Canada from 1869 until the office of high commissioner was established in 1880. When Rose left Canada an order in council of 2 Oct. 1869 stated that he was “accredited to Her Majesty’s Government as a gentleman possessing the confidence of the Canadian Government with whom Her Majesty’s Government may properly communicate on Canadian affairs.” His expenses were underwritten by the dominion but he received no salary. He soon proved his usefulness in coping with the problems resulting from Canada’s acquisition of the northwest. “It is impossible to have an abler or more pleasant man with whom to transact business,” Granville reported to Macdonald in 1870. The connection with Ottawa was maintained by the Liberal prime minister, Alexander Mackenzie*, upon whose suggestion Rose became the “Financial Commissioner for the Dominion of Canada” by order in council of 5 March 1875. But the comfortable association between Rose’s financial activities and the informal agency of Canada could not be maintained indefinitely. In the summer of 1879, after the return of the Conservatives to power, Macdonald decided that a full-time official representative was needed in London. In August, on a visit to England, he informed Rose that Sir Alexander Galt would be appointed to the new position. Rose accepted the decision with his usual aplomb, and continued to be consulted by the dominion on financial and other matters even after Galt had taken up his duties. In May 1888, for instance, Sir Richard John Cartwright* complained in the house that Rose had gained commissions on a loan transaction that should have been undertaken by the high commissioner’s office. Sir Charles Tupper*, minister of finance and high commissioner, explained that Rose, as a trustee of Canada’s sinking fund in London, was entitled to remuneration for services.

It is impossible to record fully the subjects with which Rose dealt as an unofficial agent for Canada. Almost every item of substance in the bilateral relationship received his attention. Sometimes this attention was expressed in confidential advice to Macdonald, sometimes in negotiations with the relevant departments of the British government, sometimes in writing to the newspapers on Canadian affairs. In addition Rose was often consulted by the Colonial Office or by British politicians on colonial questions. Here he showed an awareness of the empire as a whole and of what he considered the beneficial and reinforcing relationships between its parts. Not surprisingly he defended the status quo in the constitutional position of the self-governing colonies and in the means of conducting imperial relations. Basically detached from British party politics, Rose carried out his representations “behind the scenes,” skilfully drawing upon his wide circle of connections in government and business for his purposes.

Honours and assets

Colonial affairs did not occupy all of Rose’s time in England. In 1883 his acquaintance with the Prince of Wales led to his appointment as receiver general for the duchy of Cornwall, a historic estate whose income was reserved for the benefit of the heir apparent to the throne. In this post Rose managed an income of about £60,000 a year from properties in Cornwall and others in Kensington and Lambeth (both now part of London). He thus made a contribution to the unprecedented circumstance of Edward VII’s accession in 1901 entirely free from debt. His membership in the prince’s circle also brought Rose service on commissions concerned with various colonial and Indian exhibitions, projects in which Edward took a keen interest. Rose served on two royal commissions, one on copyright in 1875, the other on extradition in the following year. His honours are impressive: kcmg in 1870, shortly after he removed to England; a baronetcy, Rose of Montreal, in 1872 for his role in arranging the Washington conference; promotion to gcmg in 1878; and membership in the imperial Privy Council in 1886 (his friend Macdonald had been the only Canadian to receive this honour before him).

Rose was married twice. His first wife, whom he married on 3 July 1843, was Charlotte Temple of Vermont, widow of Irish poet Robert Sweeney, who had been involved in a celebrated duel in Montreal in 1838; she and Sir John were to have three sons and two daughters. An English friend described Lady Rose thus: “I have in a long life met many women I thought clever, but never one so clever as she was, or with such a genius for society.” She died on 3 Dec. 1883, and on 24 Jan. 1887 Rose married Julia Charlotte Sophia Mackenzie-Stewart, widow of the 9th Marquis of Tweeddale. Rose himself died unexpectedly on 24 August of the following year, while deer stalking on the estate of the Duke of Portland in Scotland. Afflicted with a weak heart, he died in the excitement of shooting a stag. He was buried in Guildford, England, near a country estate, Losely Park, which he had rented for some years.

Rose is the quintessential representative of the North Atlantic community of the middle and late 19th century. Born in one corner of the Atlantic “triangle,” he made his name in another, was closely connected with the third, and returned to his birthplace to fulfil a second career. Much more a financier and diplomat than a politician, he recognized the importance of a favourable political climate for the growth of economic enterprise. Thus he turned his natural gifts to the maintenance of reinforcing relationships between the corners of the “triangle.” He was immensely aided in this task by his orderly mind, his grasp of detail, his discretion, his ability to inspire trust, and his charm and urbanity. These personal qualities were combined with a shrewd appreciation of the possibilities for financial gain and Rose died a wealthy man; his estate was valued at over £300,000. The extent to which his diplomatic and administrative achievements assisted his position as a private financier is impossible to measure but the value of the link cannot be doubted. He possessed a host of acquaintances and some close relationships with men in high places. Of the latter his friendship with Macdonald is uppermost. “Of all Sir John Macdonald’s political associates in his later years,” wrote Sir Joseph Pope*, “I am disposed to consider that, personally, he was most attached to Sir John Rose. . . .” John Morley’s appraisal fairly characterizes the man: “He was one of the many Scots who have carried the British flag . . . over the face of the globe; his qualities had raised him to great prominence in Canada; he had enjoyed good opportunities of measuring the American ground; he was shrewd, wise, well read in the ways of men and the book of the world, and he had besides the virtue of being pleasant.”

[There is no biography of Rose, nor have his private papers been located. A large mass of Rose correspondence extending over many years is contained in the Macdonald papers (MG 26, A) in the PAC. Rose was Barings’ agent in Canada and the Baring Brothers and Company papers (PAC, MG 24, D21) contain his reports to the firm. The Alexander Mackenzie papers (MG 26, B) in the PAC also include Rose correspondence. There are Rose papers for the years 1850 to 1867 in the McLennan Library, McGill University Libraries (Montreal). Rose material may also be obtained in the L. P. Morton papers in the New York Public Library. Letters and memoranda from Rose are to be found throughout Colonial Office (CO 42 and CO 43) and Foreign Office (FO 5, FO 362, and FO 414) records in the PRO and in the files of the Department of State (RG 59) in the National Archives of the United States (Washington). Original material arising from Rose’s reciprocity discussions in 1869 is reproduced in two notes edited by A. H. U. Colquhoun, CHR, 1 (1920): 54–60, and 8 (1927): 233–42. Rose’s activities touched so many branches of government that evidence concerning them is widely scattered. There is also the fact that the unofficial character of his duties after 1869 tended to reduce formal communications.

Biographical sketches of Rose may be found in Canadian directory of parl. (J. K. Johnson); Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose, 1886); Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, IV: 70–72; DNB; Dominion annual register, 1880–85; and Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians, 637–39. Secondary material is also scattered through biographies and memoirs of Rose’s friends and associates in three countries, notably Creighton, Macdonald, young politician and Macdonald, old chieftain, and Joseph Pope, Memoirs of the Right Honourable Sir John Alexander Macdonald, G.C.B., first prime minister of the Dominion of Canada (rev. ed., Toronto, 1930). There are also a few more specialized treatments of phases in his career. Rose’s involvement in the controversy over the construction of the Parliament Buildings is touched on in Hodgetts, Pioneer public service, chap.12. There is a discussion of the genesis of the Oregon Treaty in J. S. Galbraith, The Hudson’s Bay Company as an imperial factor, 1821–1869 ([Toronto], 1957), chap.13. The struggle over the dominion’s first banking legislation is discussed in D. C. Masters, “Toronto vs. Montreal: the struggle for financial hegemony, 1860–1875,” CHR, 22 (1941): 133–46; Shortt, “Hist. of Canadian currency, banking and exchange: government versus bank circulation,” Canadian Banker, 12: 14–35; and Denison, Canada’s first bank. Rose’s financial activities are touched on in Heather Gilbert, Awakening continent: the life of Lord Mount Stephen . . . (Aberdeen, Scot., 1965) and in Dolores Greenberg, “Yankee financiers and the establishment of trans-Atlantic partnerships: a re-examination,” Business Hist. (London), 16 (1974): 17–35, and “A study of capital alliances: the St Paul & Pacific,” CHR, 57 (1976): 25–39. The fullest treatment of Rose as Canadian agent in Britain is M. H. Long, “Sir John Rose and the informal beginnings of the Canadian high commissionership,” CHR, 12 (1931): 23–43. See also D. M. L. Farr, “Sir John Rose and imperial relations: an episode in Gladstone’s first administration,” CHR, 33 (1952): 19–38, and The Colonial Office and Canada, 1867–1887 (Toronto, 1955). There is a chapter on Rose as unofficial agent in London in W. I. Smith, “The origins and early development of the office of high commissioner”

Bibliography for the revised version:

National Records of Scot. (Edinburgh), OPR Births & Baptisms, Auchterless (Aberdeen), 2 Aug. 1820: www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk (consulted 17 June 2024).

Cite This Article

David M. L. Farr, “ROSE, Sir JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rose_john_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rose_john_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | David M. L. Farr |

| Title of Article: | ROSE, Sir JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |