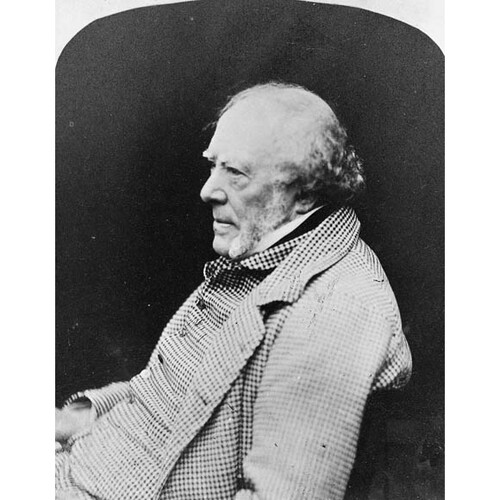

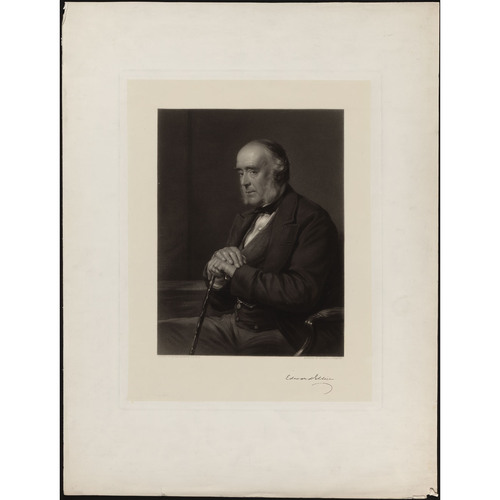

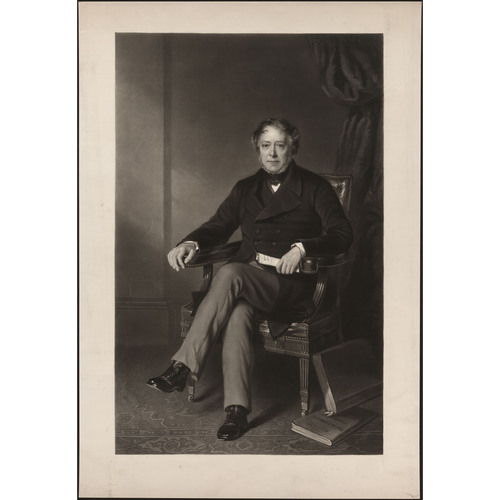

ELLICE, EDWARD, merchant-banker, landowner, and politician; b. 23 or perhaps 27 Sept. 1783 in London, England, second son of Alexander Ellice* and Ann (Anne) Russell; m. first on 30 Oct. 1809 Lady Hannah Althea Bettesworth, née Grey, daughter of Charles, 1st Earl Grey; m. secondly on 25 Oct. 1843 Lady Anne Amelia Leicester, née Keppel, daughter of the 4th Earl of Albemarle; d. 17 Sept. 1863 at Glen Quoich, near Glengarry, Scotland.

Edward Ellice (nicknamed “The Bear,” probably for his financial acumen) derived his North American ties from the commercial interests and landholdings he inherited. His Scottish father and four uncles, having established themselves in the fur trade and other ventures in Schenectady (N.Y.), extended their operations in the 1770s to London and Montreal. Though amassing and retaining large investments in New York, increasingly the family business was conducted by Robert Ellice and Company in Canada and by Phyn, Ellice, and Company in England. These firms concentrated on the financing, provisioning, and marketing aspects of the fur trade, as agents for the North West Company, the XY Company, and the reorganized North West Company. Alexander Ellice established other important links with Canada when, in 1780, he married Ann Russell in Montreal, and when, on 30 July 1795, he purchased the seigneury of Villechauve, commonly called Beauharnois, a largely undeveloped estate of 324 square miles, west of Montreal on the south shore of the St Lawrence.

Little is known of Edward Ellice’s early life within his family, which “commuted” between London and Montreal. He was enrolled in the public school at Winchester, and in 1797 he matriculated at Marischal College, Aberdeen, from which he graduated in 1800 with an ma. He entered his father’s London establishment as a clerk and soon became its principal figure; after his father’s death in 1805, he acquired control of the estate and the family’s commercial empire. Ellice quickly became a prominent merchant-banker and shipowner in the City, trading in furs, fish, sugar, cotton, and general merchandise in North and South America, the East and West Indies, and Europe. With his special interests in North America, he emerged as a spokesman for the “Canada Trade” and helped found the Canada Club in 1810 to pressure the government on behalf of colonial commerce.

Ellice made extended visits to Canada and the United States between 1802 and 1807. Noting the ruinous rivalry among the Montreal trading houses, and their competition with the Americans and the Hudson’s Bay Company, he unsuccessfully offered in 1804 to purchase the outstanding shares of the HBC for £103,000, hoping to amalgamate and rationalize the Canadian trade and thus to profit personally. The incident is evidence of Ellice’s sharpness and rapid ascent in the business world. Similarly indicative is the facility with which he borrowed £150,000 in 1813 from the Bank of England to ease a war-induced cash shortage in his business dealings.

The “empire of the beaver” was a source of personal wealth, and, in Ellice’s view, strategically important to Britain in her evolving rivalry with the United States. Between 1805 and 1820 Ellice augmented his role in the fur trade, extending large lines of credit to the NWC, and personally disposing of its furs on the London market with great shrewdness. Although there was occasional friction with the wintering and Montreal partners, the relationship with Forsyth, Richardson, and Company and with McGillivrays, Thain, and Company was generally good, that with Mackenzie and Company less satisfactory. In 1815 Ellice offered to become the sole London agent for the Montreal-based trade but its persistent divisions prevented such a rearrangement. With a view to hampering the ambitions of Lord Selkirk [Douglas*], Ellice also purchased a small interest in the HBC, enabling him to challenge, albeit unsuccessfully, the Red River grant in 1812. Ellice early questioned the validity of the HBC monopoly; when that proved unassailable, he promoted the merger of the NWC and HBC, waging a propaganda campaign and petitioning the British government to resolve the worsening situation in North America. Finally, in 1820, Ellice (and by virtue of his financial resources, probably Ellice alone) was able to bring to fruition the negotiations which saved both companies from bankruptcy. The arrangement agreed to by Ellice, Simon* and William McGillivray*, and Andrew Colvile resulted in the consolidation of the trade under a reorganized Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821. Their precarious financial affairs made the solution acceptable to the Montreal merchants and the old HBC; by hastening the necessary legislation through parliament and securing the subsequent royal grant licensing the new concern, Ellice presented the wintering partners with a fait accompli which they were powerless to resist. After another reorganization in 1824, and the bankruptcy of McGillivrays, Thain, and Company, Ellice, now a director of the HBC, emerged as the sole representative of the former NWC active in the trade. He was ensured a substantial continuing income, especially after he aggressively assumed the liabilities of the collapsing Montreal partners in exchange for their HBC shares. The most important result of the merger, however, and perhaps the most satisfying for Ellice, was the retention under British control of the western territory, now much enlarged by the terms of the 1821 licence.

Ellice’s intimate connections with the financial and political élite proved valuable to the new HBC. For example, in 1837, taking advantage of Ellice’s influence with the Melbourne government, the company sought a renewal of its licence five years before the scheduled expiration. Similarly, when the initial influx of American settlers into Oregon threatened the company’s operations there, Ellice consulted the ambassador of the United States about how to avoid a confrontation. It was suggested that the United States would relinquish its pretensions to the area north of the Columbia River if Britain agreed to concede part of her claim to the contested territory along the Maine-New Brunswick border. An accommodation of these two territorial disputes could not be reached before Melbourne’s ministry fell in 1841, but Ellice, over the strenuous objections of Lord Palmerston, the former foreign secretary, persuaded the Whigs, now in opposition, to accept the Webster-Ashburton Treaty. Then, when the Oregon question appeared ripe for resolution in 1844–45, Foreign Secretary Aberdeen sought Ellice’s advice, which was that the HBC had no absolute need for the territory between the Columbia River and the 49th parallel. The British government now had an excellent bargaining lever, for it could appear to compromise with the Americans, allowing President James Knox Polk to secure Senate approval for the Oregon Treaty. It might be questioned whether the conceded territory was unnecessarily abandoned, but the possibility of war and/or incessant riparian boundary disputes suggests that Ellice’s advocacy of the artificial boundary had much to recommend it. His support of compromise in both disputes was based upon a realistic perception of the position and long-term interests of Britain. The maintenance by the HBC of its position, and hence a British presence, in what became British Columbia served the interests both of the company and of Canada.

In the 1850s substantial challenges to the HBC appeared; in Canada, dissatisfaction was aroused because the company’s control over the Red River area was a barrier to settlement; in England, envy of its exclusive trading privileges and ideological objections to monopoly, which was regarded as anachronistic in the era of free trade, kindled antagonism. In and out of parliament Ellice successfully turned back repeated attempts to test the validity of the HBC charter. Using his access to the cabinet, his parliamentary seat, his City connections, and his carefully cultivated liaison with the press, Ellice guarded the company’s position. British administrations, by no means hostile to the company, found Ellice a useful intermediary. As unofficial spokesman for the HBC – he refused an invitation to become governor for personal reasons and for fear of adding fuel to the controversy – Ellice laid out the terms which, after much delay, settled the company’s status. In response to a petition of the Canadian ministry, the Colonial Office succeeded in having the famous select committee of the House of Commons appointed in 1857. Ellice employed customary behind-the-scenes legerdemain. The committee’s report upheld the charter and recommended renewal of the licence with the understanding that some territory would be ceded, if and when desired by Canada, providing Canada undertook to maintain order in the transferred area. No mention was made of compensation for the company – Ellice had earlier informed the government that £1,000,000 would be required – but in other respects the report endorsed Ellice’s previous position. In June 1863, after political mismanagement and confusion, a settlement satisfactory to the HBC governing board was made whereby the chartered rights and territorial claims were sold for £1,500,000 cash to a group of investors headed by Edward William Watkin. Ellice now disposed of his remaining interest in the company which, he was fond of saying with modest exaggeration, “I built . . . as it now is.” No longer as optimistic about the maintenance of order and authority in the west, he looked back on the not inconsiderable achievements of the HBC with pride. It was left to others to arrange the transfer of the territory to Canada, thus ensuring that it remained out of American hands.

Edward “Bear” Ellice, the fur baron, was also the grand seigneur of Beauharnois. For 60 years, he was concerned with the management of the inherited lands in Canada and New York, which at maximum exceeded 450,000 acres. Ellice, an absentee landlord, personally inspected his property only twice, in 1836 and 1858, yet he tried to give as much personal direction as he could, especially to the seigneury. From all appearances, the censitaires were satisfied with Ellice as seigneur. Actual management of all his holdings, and of the income derived from them, was necessarily entrusted to resident agents and to Ellice’s commercial connections in Montreal and New York. It was difficult for Ellice to cope with legislative restrictions and judicial challenges, and with agents who occasionally ignored his instructions, but he could never bring himself to emigrate to end these frustrations.

Ellice gradually sold parts of his New York and Upper Canadian lands but the seigneury at Beauharnois and adjacent land in Godmanchester and Hinchinbrook townships were not as easily disposed of. Ellice’s expenditures to develop his estates prior to the 1830s often exceeded his income; for example, on the seigneury alone he built numerous mills, schools, churches, post offices, taverns, a court house, stage depots, and steamboat wharves. He underwrote road construction and surveys in 1834 for a canal on the St Lawrence (the Beauharnois) and in 1836 for a railway south from Montreal via the seigneury toward Albany. The resident agent at Beauharnois ran a model farm, complete with imported breeding stock.

Such outlays for the seigneury could only be profitable with sufficient settlement. In the 1820s Ellice began to try to eliminate the system of feudal tenure which prevented him from disposing of individual parcels in fee simple. This was the aim of the Canada Tenures Act of 1825, an outgrowth of the Union Bill of 1822 which Ellice had unsuccessfully promoted. Under the act, Ellice chose to effect a re-grant of the seigneury in 1830. This permitted lands to be sold outright, although only 10,000 acres could be sold in the ensuing decade. The tenure issue remained a bone of contention until 1854, when Canadian legislation was passed establishing workable financial arrangements. In the interim, Ellice sold the entire seigneury in 1839 for £150,000. However, the purchaser, the North American Colonial Association of Ireland [see Edward Gibbon Wakefield], suffered from inefficient management and insufficient capital, and Ellice had to repossess the seigneury to protect his investment.

Ellice had other business interests in North America. His largest and most profitable investments were in the United States, but at various times his portfolio included investments in Canadian harbour and railway bonds, government securities, the Welland Canal Company, the Canada Company, and the Bank of Upper Canada. He regularly took back mortgages on lands he sold. In the last 25 years of his life, all of his North American investments, including the fur trade and land, probably generated a gross annual income approaching £20,000, no mean fortune for the times. Various expenses reduced this figure by at least 25 per cent, and a significant portion of the remainder was reinvested in North America.

Ellice was often accused in the press of exploiting his political and financial position to benefit himself and his fellow investors at the expense of the Canadian population. Certainly he never neglected his own interests – he told his son: “Politics must never be allowed to interfere with business” – but the criticism was not entirely warranted. In some cases, such as the Welland Canal Company and Canada Company, Ellice’s holdings were small, and taken up contrary to his business judgement. Indeed, in these two instances and others, he was highly critical of the management and deplored the consequences for Canada. Moreover, despite the low rate of return which his British North American investments yielded, Ellice for more than 60 years made significant efforts to improve economic conditions.

The most important contributions made by Ellice, moreover, did not appear in his account books; rather, they lay in the reformulation of British policy towards North America during this crucial period. Ellice possessed three assets which gave him an almost unique influence: his knowledge of the North American situation was unmatched among his contemporaries in Britain; he had a large and sustained personal incentive in seeing that nothing of importance affecting North America went unnoticed in London; and, by virtue of his ready access to the councils of decision over some 50 years, he enjoyed unusual political leverage by which he repeatedly pressured the British government to take action he judged necessary for the Anglo-American-Canadian situation.

Ellice’s first marriage, to Lady Hannah Althea Grey, gave an entrée to the Whig aristocracy and the means to embark on a lifelong career in politics. Elected to the House of Commons in 1818, he became the principal Whig spokesman on finance, banking, and trade. A leading liberal or “Radical” in the party, Ellice became chief election manager, party publicist, and chief whip in the House of Commons when the Whigs took office in 1830 under his brother-in-law, Earl Grey [Charles Grey]. Ellice’s success in these party endeavours was the result of strenuous exertion, discretion, numerous contacts with all shades of political opinion, and innovative party management. He insisted on the adoption of a general caucus of the Whigs, devised the party Registration associations – two lasting features of British politics – and played an active role in the adoption of the Reform Act of 1832 and the Emancipation Act of 1833. As secretary of the Treasury (1830–32) and secretary-at-war (1833–34), and as a private member until his death, he furnished a liaison between the numerous factions, such as that of Lord Durham [Lambton*] and his “Radical” supporters, which made up the Whig and, subsequently, Liberal parties.

In the two decades after the collapse of Lord Melbourne’s ministry in 1841, Ellice refused repeated requests to enter the cabinet or accept a colonial post, or to go to the House of Lords to augment party strength there. He became instead the “Nestor” of his party. Financially secure, the owner of an extensive estate in the Scottish Highlands and a luxurious town-house in London, he refused to retire from politics. He attended parliament regularly, and was actively concerned about all the major issues under debate. Leaders of both parties called upon him for assistance and advice.

The precarious balance of political power in Britain enabled Ellice to exert a measurable influence on the re-orientation of British imperial policy on behalf of freer trade, stimulation of colonial economic development, and gradual devolution of the empire. For instance, he was highly critical of the government’s policy towards the Canada Company, pointing out on several occasions how a more realistic system of land sales might speed development. His most notable early effort to remedy the slow pace of Canadian development came in the abortive Union Bill of 1822 [see John Beverley Robinson and Louis-Joseph Papineau*]. Ellice persuaded the ministry to draft a bill largely along lines he suggested and to introduce it in the House of Commons. He had previously secured what he regarded as a commitment from other members to forego extensive debate, believing that only a fait accompli could succeed in preventing further French obstruction and in fostering English predominance in Lower Canada. When criticism was unexpectedly voiced in the house, the embattled ministry abandoned the scheme. Only the Canada Trade Act (1822) and, ultimately, the Canada Tenures Act (1825) were salvaged from the original proposal, measures which sought to meet some of the problems confronting the English minority. An important result of the episode – an ironic one in view of mounting criticism of Ellice as a malevolent “conspirateur” – was Ellice’s growing realization of the difficulties of legislating for the colonies from London, and a reinforced determination to contemplate self-government for them. This advanced position is clear from his testimony to the Canada Committee of the House of Commons in 1828, and from his advice to the Colonial Office and to colonial governors such as Sir James Kempt* in the 1820s and 1830s. Unfortunately, successive ministries “cared nothing for Canada except as an occasional makeweight in the political game.” It required the rebellions of 1837–38, which threatened the Melbourne government, to create a situation that could no longer be ignored.

Ellice made an extended visit to North America in June-October 1836, and in the wake of the 1837 rebellions he saw an opportunity to pressure the government into decisive action. In early January 1838 he first presented to Sir Henry George Grey a concise proposal for a federal union of the two Canadas, and a limited measure of ministerial responsibility. He revived the suggestion that Lord Durham be sent as governor general, with “large powers both for the exercise of authority and conciliation.” After consulting Ellice, Durham agreed to undertake the mission. Ellice gave Durham advice and introductions to colonial society, and safeguarded in parliament and the cabinet Durham’s freedom of action. Ellice also persuaded his son Edward to accompany Durham as his private secretary. In the course of Durham’s mission, Ellice continued his liaison between the Melbourne ministry and its mercurial representative, and tried to cushion the impact of some of Durham’s actions (such as the appointments of Thomas Edward Michell Turton and Wakefield). When the ministry abandoned Durham over the banishment of the leading rebels, Ellice continued his efforts to ensure that Durham would produce recommendations and to prevent Melbourne’s ministry from collapsing under political pressure. But while Durham was still in Canada, Ellice denounced in the press the reported proposals for a highly democratic, all-inclusive federation of the North America colonies as too difficult to achieve. When Durham returned to London in anger at the end of November 1838, Ellice succeeded in persuading him to abandon such a scheme, and to adopt several features from his own memorandum, “Suggestions for scheme for the future government of the Canadas” (21 Dec. 1838), recommending a federal union of the two provinces. Each of the principal recommendations of Durham’s famous Report, semantic differences notwithstanding, had been advanced in Ellice’s memorandum.

The leaking of the Report in early February 1839, in which Ellice may have had a hand, forced the ministry to move. It was a politically explosive issue for Melbourne’s tenuous coalition. The cabinet first considered Ellice’s “Suggestions,” agreed upon them as a basis for legislation, and ordered printing of a bill based on them. However, this decision was reversed two days later. Finally, after two aggravating months, Lord John Russell, the new colonial secretary, proposed two measures, providing for temporary continuation of the emergency power in the hands of a new governor, and recommending Ellice’s scheme of union; the first narrowly passed, and it was agreed that consideration of the second would await dispatch of Durham’s successor.

Despite the severe strain these events imposed on his relations with the cabinet, Ellice continued his efforts. He provided Charles Edward Poulett Thomson* (Lord Sydenham), Durham’s successor, with “advice and assistance” and he reiterated to Russell the need to give Thomson adequate authority to deal with the pressing financial and political crisis; he insisted that “the principle of union being determined upon, it is infinitely better to allow people to settle for themselves, the conditions and provisions, on which it may appear most expedient for the interests of both provinces to carry it into effect.” Thomson’s instructions and Russell’s famous dispatch of 16 Oct. 1839 testify to the imprint of such thinking, when the government remained opposed in principle to “responsible government.”

Thomson established a coalition ministry in February 1840; the British government reintroduced its bill in March, and Ellice gave the measure his “unqualified approbation” though he had some doubts about the legislative union now proposed. In June, Ellice (using the leverage of Tory pressure) induced the ministry to drop certain “municipal clauses” deemed a threat to property holders, and the act was finally passed. The measure, which paved the way for responsible government as it evolved in practice under Sydenham, Sir Charles Bagot*, Sir Charles Theophilus Metcalfe*, and Lord Elgin [Bruce], represented the consummation of Ellice’s efforts to force upon a most reluctant ministry some realistic proposals for colonial reform and confederation. It was Ellice’s hope that with this step Canada would remain a British state, with sufficient economic self-reliance to resist the dynamic encroachment of the United States, and would advance politically to the point of managing its own destiny effectively. Such hopes might not be fulfilled until at least 1867, but the decisions taken in 1839–40 came at an important, possibly critical, juncture in the transformation of the British colonial system. In these decisions Ellice made his greatest impact on imperial policy.

After 1841 Ellice took a less dramatic but not insignificant part in the making of imperial policy. He proved sympathetic, for instance, to Bagot’s efforts to bring Robert Baldwin* and Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine into the government. When the implications of freer trade and responsible government were revealed in the increases in Canadian tariffs and the passage of the Rebellion Losses Act, Ellice accepted the colonial action in principle but questioned the perpetuation of British governance. Fear of possible civil strife and possible American intervention, however, persuaded him against Britain’s precipitate withdrawal. Rather, Ellice urged that the British government consider again a federation of the North American colonies, and pursue reciprocal trade arrangements between them and the United States.

In the 1850s Ellice further suspected the efficacy of British colonial policy, in the face of ever increasing colonial self-confidence. He became convinced that “no British administration can be tempted again to dispute the sovereign will of the Canadian people, fairly represented in their legislature.” Yet he hoped that Britain would still act to guard against “their passions and impulses” and preserve individual rights and liberties. But in the latter years of the decade, with the Canadians opting for what Ellice considered excessive democracy, leading to political deadlock and fiscal insolvency, he found less virtue in maintaining the imperial connection. He saw no reason to subject the British crown to unnecessary embarrassment and responsibility, though he insisted that the colonists themselves should cut the “silken thread.” These views found resonance in both Conservative and Liberal administrations.

Ellice’s last visit to the United States and Canada in 1858 reinforced his impression of the growing strength of the former and its impact on Anglo-American relations. His concern was evident in his approach to the HBC, and explicitly set forth in a lengthy and perceptive memorandum on the colonies submitted at the Duke of Newcastle’s request in 1861. He urged again the adoption of a federal system comparable to his 1838 scheme which he alleged had been rejected as “too great a parody on the American Constitution.” Some such step he saw as the only means of preventing the annexation of British North America to the American union, an eventuality made more likely, he argued, by the American Civil War.

Death brought Edward Ellice’s long career to an end shortly before confederation, preventing him from seeing his goal achieved. In his final years Ellice’s only son, Edward, and his daughter-in-law, Katherine Jane Balfour, were his frequent companions. Edward, who was an mp almost as long as his father, was also a businessman, with interests ranging from the HBC, of which he became deputy governor in 1858, to financially disastrous Scottish railways. Though he assisted for a time in the management of the Ellice North American investments and acted as interrogator for his father on the HBC select committee, Edward Jr had but slight contact with North American affairs in later life. The sale of the seigneury in 1867 to the Montreal Investment Association marked the passing of that Ellice connection with North America.

Edward “Bear” Ellice may never have forgotten his immediate self-interest when Canada was involved, but it would be hard to argue that the policies he recommended, and the information he supplied to British and Canadian ministries and to American cabinets, was inimical to their long-term mutual interests. Far from being simply an entrepreneur concerned with profits and power, he proved consistently broadminded, perceptive, and determined to pursue a policy solely on its merits. If he shared prevailing British and American assumptions about the place of the French populace in an English colony, he was at least able to temper the prejudices of his colleagues (Lord Durham included) and insist on a measure of equity for both founding peoples. Much of what he proposed was not taken up immediately; the results of the delay – rebellion, bloodshed, financial distress, and retarded political and economic maturity – were the very consequences Ellice worked so hard to avoid. Edward Ellice was a man with a passion for anonymity; yet the letters of condolences which poured in to Glen Quoich from people in all walks of life bear eloquent testimony to the wisdom, warmth, and generosity of a man whose important contributions to the expansion and survival of the British empire in North America ought not to be overlooked.

[There has been to date no complete biography of Edward Ellice. The material contained herein is drawn largely from my thesis, “Edward Ellice and North America” (unpublished phd thesis, Princeton University, Princeton, N.J., 1971) and from research on Ellice’s career after 1841 undertaken for that dissertation but not included therein because of limitations on length. The only other studies of Ellice are one now in progress by John Clarke, fellow of All Soul’s College, Oxford, and one by D. E. T. Long, “Edward Ellice” (unpublished phd thesis, University of Toronto, 1941).

Of necessity, the above account relies largely on primary materials. The major source of manuscript material on Ellice is the Ellice papers, National Library of Scotland (Edinburgh). Copies of a portion of this collection are found in PAC, MG 24, A2. Other important British manuscript sources are the Grey of Howick papers at University of Durham, Dept. of Palæography and Diplomatic (2nd Earl Grey, box 13; 3rd Earl Grey, boxes 84–88, 142); the Lord John Russell papers at the PRO (PRO 30/22), and at the British Museum (Add. mss 38080); the Holland House papers and 1st Viscount Halifax papers at the British Museum (Add. mss 51587 and 49531–93); the 1st Lord Brougham papers and Joseph Parkes papers at University College Library, University of London; the 1st Viscount Halifax papers (A 4/103/1) in the archives of the Earl of Halifax, Garrowby (Yorkshire, Eng.), and the Lambton papers in the archives of the Earl of Durham, Lambton Castle (County Durham, Eng.). Other scattered (but occasionally important) sources in Great Britain, Canada, and the United States are listed in the bibliography of my thesis.

Ellice, by inclination a man with a passion for anonymity, has largely escaped the sustained attention of previous historians. Different aspects of his career are touched upon in: J. S. Galbraith, The Hudson’s Bay Company as an imperial factor, 1821–1869 (Toronto, 1957); Arthur Aspinall, Politics and the press, c. 1780–1850 (London, 1949); Austin Mitchell, The Whigs in opposition, 1815–1830 (London, 1967); D. H. Close, “The general elections of 1835 and 1837 in England and Wales” (unpublished d phil thesis, Oxford University, 1967); R. H. Fleming, “Phyn, Ellice and Company of Schenectady,” University of Toronto Studies, History and Economics, Contributions to Canadian Economics, IV (1932), 7–41; W. S. Wallace, “Forsyth, Richardson and Company in the fur trade,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., XXXIV (1940), sect.ii, 187–94. Passing reference is made to the non-North American aspects of Ellice’s multifaceted career in studies of British and Continental politics, economic development, imperialism, and in many contemporary diaries, journals and other accounts, cited in my bibliography. j.m.c.]

Cite This Article

James M. Colthart, “ELLICE, EDWARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ellice_edward_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ellice_edward_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | James M. Colthart |

| Title of Article: | ELLICE, EDWARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | December 19, 2025 |