NELSON, ROBERT, doctor, member of the assembly, Patriote; b. January 1794 in Montreal, son of William Nelson and Jane Dies; d. 1 March 1873 at Gifford, Staten Island, N.Y.

William Nelson, the son of a commissary in the Royal Navy, and originally from Nesham, Yorkshire, was a teacher in New York, where he married Jane Dies, whose father owned large estates on the Hudson River. After the American Revolution (during which he was probably an officer in the Royal Navy), he moved to Montreal. It was there that his younger son Robert was born.

Robert Nelson studied medicine, first at Montreal under the famous Dr Daniel Arnoldi*, then at Harvard University. On 15 April 1814 he received authorization to practise. War was at its height; the young doctor enlisted in the army and was immediately appointed surgeon in ordinary to the 7th Battalion, called Deschambault’s force (after Colonel Louis-Joseph Fleury Deschambault). Later, in 1824, with these wartime comrades, he was to sign a petition to Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*], to obtain land that the veterans had been promised. On 26 July 1814 he was transferred to the corps of Indian braves, where an epidemic of what was apparently lithiasis was raging. Nelson retained his affection for the Indians after the hostilities were over. At least until 1826 he worked on a voluntary basis among the 3,000 inhabitants of the reserves at Caughnawaga, Lac-des-Deux-Montagnes (Oka), Saint-Régis, and Saint-François. Twice, in 1821 and at the time of a syphilis epidemic in 1826, he asked Lord Dalhousie, in vain, to appoint him surgeon to the Indians. He also spent some of his time assembling material to be used for a history of the aborigines of America, which he seems never to have completed.

Having gone to live at Montreal, the young doctor rapidly acquired an enormous clientele and a more than creditable reputation. Two of his students were Luc-Hyacinthe Masson and Charles-Christophe Malhiot. Nelson was said to be the man for difficult cases, for major operations. He is thought to have been the first man in the country to operate for stones (lithotritis). According to Laurent-Olivier David*, while on a journey in France he interrupted a surgeon who was “perplexed and in danger of following the wrong course,” and completed a delicate operation “to the applause of the doctors and students present.” In 1827 his brother Wolfred* brought him into politics. He was elected with Louis-Joseph Papineau in Montreal West. In the house he did not particularly attract attention, and, judging that his political duties did not fit in with his profession, he resigned in 1830. Two years later, on the outbreak of the cholera epidemic, he gave his services especially to the immigrants at Pointe-Saint-Charles. In 1834, for reasons that have remained obscure, he returned to politics, representing Montreal West in the assembly. He joined with the members of the Patriote party who refused to vote supplies to the government so long as the latter did not meet their chief requests for reforms. Although Nelson was one of the most vehement speakers in the Patriote assemblies of the counties and one of the most active members of the Comité Central et Permanent du district de Montréal, he did not take part in the 1837 insurrection. He was none the less arrested on 24 November as a suspect, undoubtedly because of his close association with his brother Wolfred, who was present at the battle of Saint-Denis. The next day, however, he was released because of irregularities in the warrant for his arrest. He was indignant and furious. Louis-Joseph-Amédée Papineau, in his diary, stated that Nelson wrote on the wall of his cell: “The English government will remember Robt. Nelson.” It was in this state of mind that he went to the United States at the end of 1837.

Among the other leaders who succeeded in evading the English army were L.-J. Papineau, Edmund Bailey O’Callaghan, the parish priest Étienne Chartier*, Édouard-Étienne Rodier*, Édouard-Élisée Malhiot, Cyrille-Hector-Octave Côté*, Thomas Bouthillier*, Joseph-François Davignon, and Julien Gagnon. They all arranged to meet on 2 Jan. 1838 at Middlebury, Vermont, to discuss the possibility of another insurrection. The failure of 1837 had profoundly changed the alignments in the revolutionaries’ camp. The radicals had taken over the leadership of the movement from the moderates. Among the radicals two tendencies appeared. The first favoured direct and immediate action: the setting up of a provisional government, the proclamation of a republic of Lower Canada, and the invasion of Lower Canada. Robert Nelson, supported by a group including Dr Côté and Julien Gagnon, represented this tendency. Other Patriotes, centring around Papineau, were opposed to any precipitate action without having previously obtained the assurance of formal aid from the government of the United States and the border states. The first group prevailed, and Nelson was elected general of the army and president of the future Canadian republic.

The extreme haste and enthusiasm of Nelson and his followers are no doubt to be explained by their revolutionary fervour and their indignation over recent events in Lower Canada. To these must probably be added their belief that large sectors of the American population would spontaneously support them, and that many would march by their side. This belief is understandable. The northwestern states had numerous reformers who were demanding the abolition of slavery and of imprisonment for debts, the emancipation of women, and the extension of liberty to oppressed peoples. Many of these reformers, imbued with the revolutionary excitement of 1776, were sympathetic to the cause of the Canadian, political refugees. Moreover, thousands of American unemployed, who considered the Bank of England responsible for the 1837 recession, were perhaps tempted to take advantage of an opportunity to avenge themselves on Great Britain. At least the Patriotes might believe they would be.

It was with these possibilities in mind that Nelson and his chief lieutenant, Dr Côté, prepared a first invasion for 28 Feb. 1838. After having “obtained” 250 rifles from the Elizabethtown arsenal, Nelson, at the head of 300 to 400 Patriotes, invaded Canada from Alburg, Vermont. As soon as it had cleared the border, the band distributed copies of a declaration of independence. The latter, drawn from the American Declaration of Independence, first enumerated the crimes that Great Britain had committed against Lower Canada, then set forth the right to overthrow the government. There followed 18 declarations, not untinged with propaganda, on abolition of the union of church and state, seigneurial tenure, and imprisonment for debts, the nationalization of the clergy reserves, and so on. The invasion proved to be a total failure. Scarcely had the Patriotes reached Canadian territory when they were attacked and pushed back into the United States. Nelson and others were put in prison for having infringed the American neutrality law. However, they were rapidly acquitted by a jury sympathetic to their cause.

Nelson and his friends realized that even if this failure could be imputed to a lack of preparation and organization, their own lack of discretion was also largely to blame. Hence the formation of a secret society, known as the Frères-Chasseurs. The decision to set this up was also taken with the object of getting round the new neutrality law passed by Congress in March 1838 (but requested two months earlier by the president), a law much more rigorous than the previous one.

The secret society was constituted on the model of an army. At the head of the association was the Grand Aigle, a sort of major-general; under his orders were Aigles of various districts, who were each to organize a company. To do this they chose two Castors – captains, as it were – who in their turn undertook to assume command over five corporals, commonly called Raquettes. The latter each had under their orders nine men, and these formed the corps of Chasseurs proper. The funds necessary for financing the movement were collected from among sympathizers in Lower Canada and the United States.

Nelson entrusted the recruiting to dynamic comrades such as John McDonell, Célestin Beausoleil, and Édouard-Élisée Malhiot, who travelled through Lower Canada setting up lodges and promising arms and ammunition for the great day of deliverance. The wildest and most improbable reports circulated as to the number of Frères-Chasseurs. Sir John Colborne* spoke of several tens of thousands; others commented that each parish in Lower Canada had its lodge.

Whatever the number of Frères-Chasseurs might have been, this army was hardly a disciplined one. Nelson’s leadership was not very firm. Aloof, doctrinaire, uncompromising in his ideas, he did not have the unconditional support of those of his compatriots who were the most devoted to the cause. Édouard-Élisée Malhiot, among others, would not soon forget the fate in store for Papineau. Also, Nelson did not manage to eliminate among his associates the conflicts of personality, the personal rivalries, the ambitions that would forever be obstacles to effective action. Anarchy often prevailed in this association, where each member wanted to achieve the most lofty ends.

After long discussions and numerous compromises, Nelson succeeded in getting the date of the invasion and uprising fixed for 3 Nov. 1838. On the third, according to orders, the Patriotes began to assemble in the parishes along the border, Napierville, Lacolle, and Châteauguay, where arms and reinforcements were to reach them from the United States. Impatient, and without necessarily consulting Nelson, groups of Patriotes tried isolated actions. At Beauharnois some easily occupied the seigneury of Edward Ellice* [see D. A. Macdonell] and others seized the steamship Henry Brougham, with the intention of converting it into a war vessel.

An over-all strategy had, however, been worked out by Nelson and his principal lieutenants. It would seem that after launching an offensive on the American border, by prearrangement with the force of William Lyon Mackenzie*, the Patriotes were to start simultaneous attacks against Beauharnois, Châteauguay, Laprairie, Saint-Jean, Chambly, Boucherville, and Sorel. Nelson himself, at the head of 800 men, was to make use of the Richelieu valley, capture Saint-Jean, and proceed towards Montreal. Montreal, Trois-Rivières, and Quebec were then to be attacked successively. It was hoped that meanwhile the Chasseurs of these towns would revolt from within.

This fine plan was not put into effect. At Montreal the authorities reacted quickly, and arrested several ringleaders. A number of Chasseurs, seeing that the promised arms did not arrive, attacked the Indians of Caughnawaga, with the object of seizing their weapons and ammunition. This was unlucky for them, since many of them were taken prisoner. Meanwhile confusion reigned at Napierville, where Nelson had arrived in the night of 3 or 4 November, not at the head of a band of 800 men but with two French officers: P. Touvrey and Charles Hindenlang*. There he found about 3,000 poorly armed men. And what was more, the American schooner that was coming to bring them arms and ammunition had been intercepted by Canadian volunteers. On the 5th, a detachment of about 400 Patriotes set off for Rouse’s Point, to get arms and ammunition that had been hidden there. The American authorities had confiscated them. When they returned, they were thrashed by militiamen.

The operation was turning into a complete fiasco. Nelson, realizing the danger that these incidents represented, and the threat constituted by the movements of regular troops under Colborne’s command, decided to direct his men towards Odelltown. It certainly seems that at this moment he contemplated flight. The Patriotes left Napierville on the morning of the 8th and arrived at Lacolle at the end of the afternoon. The story goes that Nelson tried to flee during the night, but that he was captured when he was preparing to get across the border and brought back bound hand and foot. He succeeded in convincing the discontented that he had set out on a tour of inspection. On 9 and 10 November the Patriotes attacked the militiamen at Odelltown. During the decisive engagement that followed the arrival of reinforcements for the militia, the Chasseurs lost 50 men; they then made their way back to the United States. Nelson had fled before the end of the fight.

It is harder to keep track of Nelson after these events. We know however that towards the end of 1838 he called Côté, Gagnon, Malhiot, Ludger Duvernay*, and Robert-Shore-Milnes Bouchette together at Swanton, Vermont. Faced with repression in Lower Canada, the firm opposition of the American government, and, within the last little while, of a large section of the American border population, the Patriote leaders had planned to modify their tactics. They decided to exploit or even provoke border incidents between the United States and Great Britain. They hoped to be able to achieve their ends during a conflict between the two countries. To no avail. The Aroostook “war,” and the incident in which Alexander McLeod was implicated, gave them a faint hope, but London and Washington, eager for peace, settled their differences in 1842 by the Webster-Ashburton treaty.

Ruined, saddled with debts, Nelson decided to go to try his luck in California, where the goldrush was at its height: in a few weeks he acquired a large fortune. However, he lost it through the dishonesty of an agent to whom he had entrusted it. Refusing to return to Canada, where he had been pardoned, he practised his profession in the west until 1863, when he took up residence in New York, in partnership with his son, Eugène (the name of Nelson’s wife is not known); Eugène, born on 28 March 1837, had just finished his medical studies in London. In 1866 Robert Nelson published, in New York, Asiatic cholera: its origin and spread in Asia, Africa, and Europe, introduced into America through Canada; remote and proximate causes, symptoms and pathology, and the various modes of treatment analysed. He also translated a medical text and several articles of interest to students of medicine.

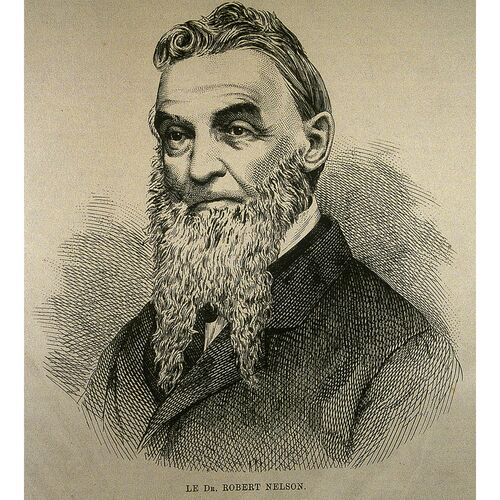

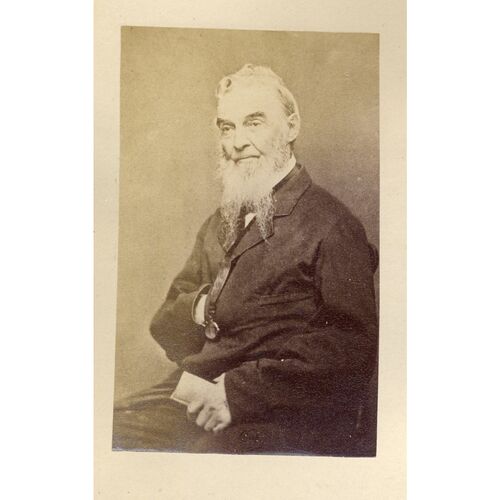

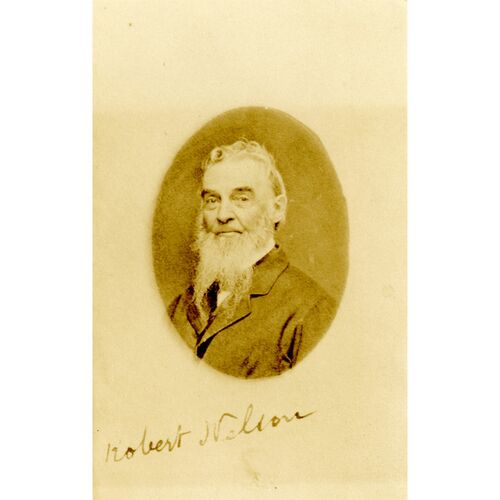

According to David, “Robert Nelson was swarthy, of medium height, but vigorous; he had a piercing eye, a keen, searching glance, a severe cast of features. He was a man of few words; his speeches were concise but energetic, he went straight to the point, openly and without mincing matters. He had a forceful, bold, original, adventurous and independent nature, and was headstrong in his opinions and feelings.” A portrait dating from the early 1870s shows him wearing a long beard.

[The most important genealogical material on Nelson and information about his early career as a doctor and member of the assembly are found in: PAC, MG 30, D62 (Audet papers), 23; RG 8, I, A1, 507, pp.48, 71–72; I, D7 1694, pp.3–4; RG 10, A5a, 18, 19. La Minerve (Montréal), 10 avril 1873. Audet, Les députés de Montréal, 233–34. L.-O. David, Biographies et portraits (Montréal, 1876); Patriotes. Wolfred Nelson, Wolfred Nelson et son temps (Montréal, 1946). L’ Union médicale du Canada (Montréal), II (1873), 188 (obituary). j.m.]

[Information on the events of 1838, the personal rivalries and intrigues that were a continual obstacle to coordinated and effective action, was drawn from ANQ, Collection Ludger Duvernay; the Canadian Antiquarian and Numismatic Journal (1908–1910); and the “Inventaire des documents relatifs aux événements de 1837 et 1838, conservés aux archives de la province de Québec,” APQ Rapport, 1925–26, 179ff. Fernand Ouellet’s article, “Papineau dans la révolution de 1837–1838,” CHA Report, 1957–58, 13–34, also contains material.

Details concerning the period from Nelson’s arrest in 1837 until his departure for the United States are found especially in Louis-Joseph-Amédée Papineau’s journal, “Journal d’un Fils de la liberté, 1837–1840.” The original is in the BNQ and there is a manuscript copy in the ANQ.

Accurate information on the establishing of the Frères-Chasseurs by Nelson is found in: A. B. Corey, The crisis of 1830–1842 in Canadian-American relations (New Haven, 1941). O. A. Kinchen, The rise and fall of the Patriots Hunters (New York, [1956]). Ivahoë Caron “Une société secrète dans le Bas-Canada en 1838: l’Association des Frères Chasseurs,” RSCT, 3rd ser., XX (1926), sect.i, 17–34. Victor Morin, “La « république canadienne » de 1838,” RHAF, II (1948–49), 483–512; “Clubs et sociétés notoires d’autrefois,” Cahiers des Dix, XV (1950), 199–203.

The Perrault papers in the State Historical Society of Wisconsin contain material on the invasion of 3 November, as do the following: Report of the state trials before a general court martial held at Montreal in 1838–9: exhibiting a complete history of the late rebellion in Lower Canada (2v., Montreal, 1839). L.-N. Carrier, Les événements de 1837–1838 (Québec, 1877), 111–16. Fauteux, Patriotes, 65–74.

Carrier’s study and the article by Victor Morin on the “republique canadienne” should be consulted also for the circumstances surrounding Nelson’s flight. r.c. and y.r.]

Cite This Article

Richard Chabot, Jacques Monet, and Yves Roby, “NELSON, ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nelson_robert_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nelson_robert_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Richard Chabot, Jacques Monet, and Yves Roby |

| Title of Article: | NELSON, ROBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |

![[Robert Nelson, M.D.] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis Original title: [Robert Nelson, M.D.] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis](/bioimages/w600.4325.jpg)