Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HINDENLANG (Hindelang), CHARLES (sometimes known as Lamartine and as Saint-Martin), Patriote; b. 29 March 1810 in Paris; d. 15 Feb. 1839 in Montreal.

Charles Hindenlang, whose family were Parisian merchants of Swiss Protestant descent, enlisted in the French army in 1830, at the time of the July revolution. He became an officer, by slow degrees moving through the lower ranks. In the autumn of 1838 he was in New York, where a French businessman by the name of Bonnefoux (Bonnafoux) recruited him for the Patriote army in Lower Canada and introduced him to Ludger Duvernay*. He took up service at the same time as another French officer, Philippe Touvrey, and two Polish officers, Oklomsky and Szesdrakowski. They were sent to Rouses Point, N.Y., where Théophile Dufort received them before sending them across the border with Robert Nelson*.

On the night of 3–4 Nov. 1838 they reached Napierville in Lower Canada. Cyrille-Hector-Octave Côté hailed Nelson as “president of the provisional government” and introduced Hindenlang as “Brigadier-General Saint-Martin.” Hindenlang was to teach tactical manœuvres to the Patriotes assembled at Napierville. But time was short. After the uprisings at Beauharnois, La Prairie, and Caughnawaga (Kahnawake) failed, Lieutenant General Sir John Colborne* decided to march towards the American border with 5,000 men. Nelson, along with Hindenlang and 600 men, hastily departed for Odelltown, a strategic point near the frontier. On 8 November they were at Lacolle and by the next morning at Odelltown, where some loyal volunteers had barricaded themselves in the church. Without even one cannon, indeed almost without arms, the Patriotes could not lay siege to the church for long and had to beat a retreat late in the afternoon. Arriving back in Napierville, they received the order to scatter. Hindenlang went off with 14 men, but he was exhausted and wound up alone with Adolphe Dugas, a young medical student. Before he could cross the border he was taken prisoner. When the British found out his identity, they sent him to Montreal, where he was put in jail on 14 November.

During the next three months Hindenlang adopted an ambiguous, even contradictory stance. When he arrived in Montreal he signed a long “declaration” stating that he had been misled by rebel leaders and harshly denouncing Nelson in particular, whom he called a rogue, coward, and traitor. He ended his confession by offering to serve the right cause to make amends for his brief aberration. This document, surprisingly, was made public in L’Ami du peuple, de l’ordre et des lois on 17 Nov. 1838, as were two letters from Hindenlang, one to his companion Touvrey and the other to a friend by the name of Henri, both thus appearing in print before the two could have received them. Hindenlang repeated to Touvrey the accusations he had levelled against Nelson, and he even spoke of magnanimity on the part of the British. Hindenlang had signed his confession at the request and in the presence of Pierre-Édouard Leclère*, a well-known justice of the peace. Touvrey, however, denied in the New York paper L’Estafette Hindenlang’s claim that he had come to New York to deal with family business. According to Touvrey, he had decided to come and fight for liberty as soon as news of the insurrection in the autumn of 1837 reached Paris. It may well be asked how the confession had been forced out of Hindenlang. Côté was to assert in the North American (Swanton, Vt) on 30 Oct. 1839 that Leclère had written a portion of it, in particular the paragraph concerning the offer to collaborate.

On 22 Jan. 1839 Hindenlang came before a court martial, with Irish lawyer Lewis Thomas Drummond* in attendance. Among the prosecution’s nine witnesses were four Canadians; one, the curé of Saint-Cyprien parish at Napierville, Noël-Laurent Amiot, stated that Hindenlang had called the Canadians cowards after the battle of Odelltown. The young Frenchman was found guilty on four counts, but the judges gave him two days to prepare his defence. On 24 January he presented two legal arguments for having the trial declared invalid: the writ summoning him before the court had incorrectly spelled his name Hindelang, and he could be tried only by his peers – a jury – since he was in a country under English criminal law. The two legal points were rejected. He then made a speech, saying that his sole mistake was to have been unsuccessful, but he refrained this time from denouncing the Patriote leaders. He was sentenced to death. Two days later he wrote a long letter to Governor Colborne, reminding him that some British subjects in Spain had done the same thing as he had, and that when they were captured, they had been considered prisoners of war and were not executed as rebels. In this letter he again excoriated Nelson for his conduct.

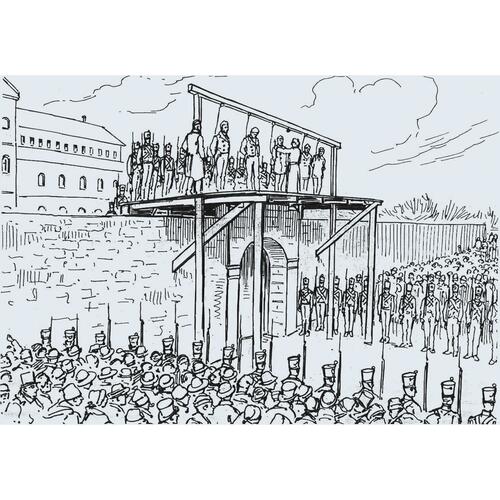

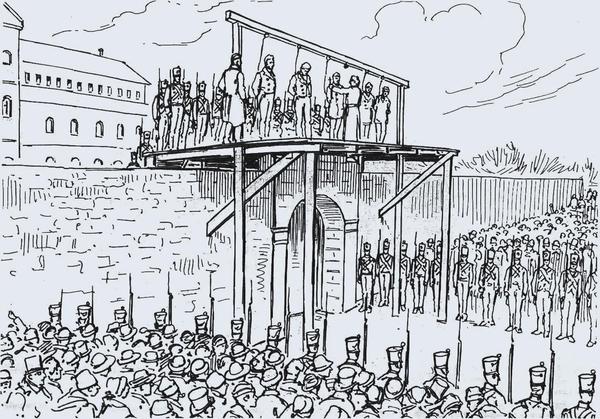

News that executions were imminent reached the Montreal jail on 12 February, and the list of the five condemned men was known the following day. At 9:00 a.m. on 15 February, Hindenlang mounted the scaffold bravely, attended by Dr John Bethune*, rector of Christ Church, Montreal. He made a short speech and cried “Vive la liberté!” From 6:00 a.m. he had been making copies of his speech for other prisoners to transcribe and pass around. Historian Mason Wade claims that Hindenlang was executed because he “refused to save his neck by turning state’s evidence.” This is quite conceivable, but there is no way of knowing whether he had indeed come to fight for freedom or to set up his father’s business. In the event it is his courageous death alongside Chevalier de Lorimier, Amable Daunais, François Nicolas, and Pierre-Rémi Narbonne that has been remembered.

Hindenlang’s activity in Lower Canada raises the question of the role played by France and the French in the rebellions of 1837–38. It is certain that the French government never took any part, from near or from afar, in the insurrections. The French ambassador to Washington, Édouard de Pontois, followed events closely, as was his duty. In the summer of 1837 he came to the valley of the St Lawrence, taking care to meet the civil authorities. He also attended a Patriote meeting at Saint-Constant, near La Prairie, and even had a meal with Louis-Joseph Papineau*. After Hindenlang’s capture he requested his British counterpart in Washington, Henry Stephen Fox, to ask Colborne to treat Hindenlang humanely. A few other natives of France in Lower Canada came out personally for or against the rebellion, most of them being sympathetic to the Patriotes. Among the latter were businessmen Victor Bréchon and Bonnefoux, actor Firmin Prud’homme, Joseph Lettoré, and others. On the English party’s side were the superior of the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice in Montreal, Joseph-Vincent Quiblier*, and journalists Alfred-Xavier Rambau* and Hyacinthe-Poirier Leblanc* de Marconnay.

The story of Charles Hindenlang in Lower Canada has a final episode. According to parish priest Étienne Chartier*, Papineau wanted to take legal action against Colborne when he learned that “le Vieux Brulôt” was returning to England. He reached an agreement with the former agent in England of the Lower Canadian assembly, John Arthur Roebuck*, to institute criminal proceedings for murder in the Court of King’s Bench. Guillaume Lévesque*, a young Montrealer who had shared Hindenlang’s cell, and Hindenlang’s own brother thought of instituting a civil action. According to Chartier, having got wind of the matter the British cabinet informed Queen Victoria and she hastened to raise Colborne to the peerage. This, to all intents and purposes, put him beyond reach of the law. Roebuck and Papineau had to give up the idea of taking legal action against Lord Seaton.

ANQ-M, P1000-3-298. ANQ-Q, E17/31, nos.2331–450; E17/37, nos.2941–3040; E17/51, nos.4101–52; P-68, nos.3–4; P1000-49-976; P1000-65-1291. AUM, P 58, U, Hindenlang to L. T. Drummond, 9, 13 Feb. 1839. PAC, MG 24, B2, 3: 3346–49, 3567–69; B143; MG 30, D56, 18: 16–17. “Confession de Charles Hindenlang (d’abord connu sous le nom de Lamartine),” BRH, 42 (1936): 622–28. “Papiers Duvernay,” Canadian Antiquarian and Numismatic Journal, 3rd ser., 5: 182–84; 7: 77–86. F.-X. Prieur, Notes d’un condamné politique de 1838 (Montréal, 1884; réimpr. 1974). Report of state trials, 2: 5–35. L’Ami du peuple, de l’ordre et des lois (Montréal), 17 nov. 1838; 9, 16 févr. 1839. North American, 30 Oct. 1839. Le Patriote canadien (Burlington, Vt.), 4 déc. 1839. Le Populaire, 10 juill. 1837. Caron, “Papiers Duvernay,” ANQ Rapport, 1926–27: 145–258. Le répertoire national (Huston; 1893), 2: 190. Christie, Hist. of L.C. (1866), 5: 250–56. David, Patriotes, 171–237. Jean Ménard, Xavier Marmier et le Canada, avec des documents inédits: relations franco-canadiennes au XIXe siècle (Québec, 1967), 179–88. Mason Wade, Les Canadiens français, de 1760 à nos jours, Adrien Venne et Francis Dufau-Labeyrie, trad. (2e éd., 2v., Ottawa, 1966), 1: 215–17. L.-O. David, “Les hommes de 37–38: Charles Hindenlang,” L’Opinion publique, 5 févr. 1880: 61–62. Ægidius Fauteux, “Les carnets d’un curieux: Charles Hindenlang ou le Lafayette malheureux du Canada,” La Patrie, 2 juin 1934: 40–41, 43. Robert La Roque de Roquebrune, “M. de Pontois et la rébellion des Canadiens français en 1837–1838,” Nova Francia (Paris), 3 (1927–8): 238–49, 273–78, 362–71; 4 (1929): 3–32, 79–100, 293–310.

Cite This Article

Claude Galarneau, “HINDENLANG (Hindelang), CHARLES (Lamartine, Saint-Martin),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hindenlang_charles_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hindenlang_charles_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Claude Galarneau |

| Title of Article: | HINDENLANG (Hindelang), CHARLES (Lamartine, Saint-Martin) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |