Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

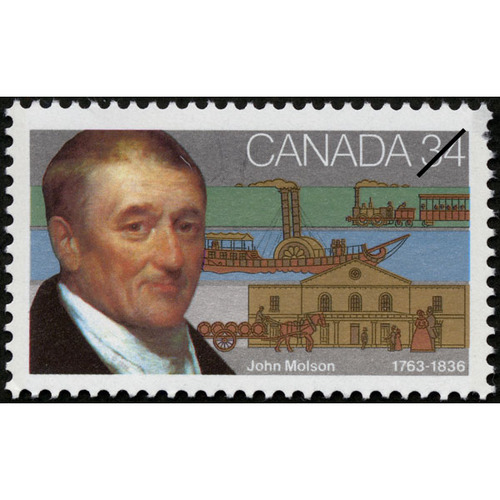

MOLSON, JOHN (John Molson Sr), businessman, landowner, militia officer, and politician; b. 28 Dec. 1763 in Moulton, Lincolnshire, England, son of John Molson and Mary Elsdale; m. 7 April 1801 Sarah Insley Vaughan in Montreal, and they had three children; d. 11 Jan. 1836 in Boucherville, Lower Canada.

Having lost his father by the time he was six and his mother when he was eight, John Molson was put under the guardianship of his maternal grandfather, Samuel Elsdale. Early in July 1782, at the age of 18, he emigrated to Montreal, and immediately became involved in various commercial endeavours with family friends who had arrived at the same time as he. He went into the meat business with the two James Pells, father and son, who were both butchers, and then he joined in a brewing enterprise which Thomas Loid (Loyd) set up that year at the foot of the Courant Sainte-Marie in the faubourg Québec.

Coming as he did from the English gentry, Molson naturally wanted to own a farm. During his first year in the colony he bought 160 hectares of land in Caldwell’s Manor, south of Montreal. He parted with it in the spring of 1786, when he began to run the brewery. He had sued Loid for repayment of a debt in the summer of 1784, and as Loid had formally admitted the justice of the case, the buildings had been seized and put up for auction. At an initial sale on 22 October there had been no offers, but at the second, held on 5 Jan. 1785, eight days after Molson had attained his majority, he was the only bidder. He put James Pell Sr in charge of the brewery and on 2 June sailed for England from New York. He could now settle his business affairs himself.

In England, Molson bought some equipment for the brewery. Returning to Montreal on 31 May 1786, he took over management of the operation. He oversaw the enlargement of the plant and began to buy grain for the coming season of malting and brewing. His first purchase, on 28 July, was an exciting event for him, as the entry in the little notebook he kept for his expenditures shows: “28th, Bot 8 bushs of Barley to Malt first this Season, Commencement on the Grand Stage of the World.” Rarely does the spirit of enterprise find such clear expression but, as a letter from Molson to his business agent in England indicated, it also spurred the Lower Canadians: “People here are more of an enterprising spirit than at home, as it is in a great measure owing to that restlessness that induces them to quit their native shore.”

During the next 20 years Molson dedicated himself to his business. He invested in it all the funds at his disposal in order to enlarge his facilities and production. It is estimated that he received about £10,000 sterling from a succession of inherited properties, including the family home, Snake Hall, which was sold on 11 June 1789. Molson had turned away from the import-export business in 1788 because the risks were too great and the profits too slow; he also foresaw that the large-scale fur trade would run into increasing difficulties. He therefore did not seek to diversify his activities during this period. In 1806 he considered opening a brewery in York (Toronto) and was warmly encouraged to do so by his correspondent D’Arcy Boulton*, who also hailed from Moulton, but nothing came of the idea.

Molson preferred to reinvest continually in his Montreal establishment and for that purpose went occasionally to England, as in 1795 and 1797, to buy equipment. The young immigrant had decided to put his money into a sector which was at the forefront of technological innovation in that country during the late 18th century. The influx of loyalists to the colony, and then the first arrivals of British immigrants, opened a market for him and soon there was a demand even from French Canadians, who had not previously been inclined to drink beer. As there was not much barley being produced in the Canadas, Molson induced farmers to grow it by initially supplying them with seed, to be paid back in kind at the rate of two bushels for one.

After his return from England in 1786, Molson had begun living with Sarah Insley Vaughan, who was four years older than he. They remained together and had three children: John*, born in 1787, Thomas*, born in 1791, and William*, born in 1793. They were married on 7 April 1801 at Christ Church in Montreal; according to the declaration they made in the marriage contract drawn up that day by notary Jonathan Abraham Gray, they wanted to acknowledge their mutual affection and legitimize their three children. Sarah signed the contract and the church register with a cross.

Not much is known about how well the young entrepreneur fitted into Montreal business circles, then dominated by the big fur merchants, most of them Scottish. From June to December 1791 and from June 1795 to June 1796 he is known to have held the masonic office of worshipful master of St Paul’s Lodge, which indicates that he had a connection with a social group who recognized him. Molson had been married in the Church of England because at the time it was the only Protestant denomination legally permitted to keep registers of births, marriages, and deaths. But as early as 1792 he had contributed financially to the building of the Scotch Presbyterian Church, later known as St Gabriel Street Church [see Duncan Fisher*], and he remained an active member until at least 1815. In this way, he associated with the community of important Scottish merchants in Montreal.

During the first decade of the 19th century, conditions arising from the Napoleonic Wars were transforming the economy of the St Lawrence valley and giving it new life: the fur trade economy was gradually replaced by the lumber economy, at a time when agriculture was expanding, particularly in Upper Canada. Steam, the new source of energy, led to technological innovations, and after a great deal of experimenting and testing, ships could be propelled with it, for a time at least, on inland water-ways. In 1807 Robert Fulton began to sail the Clermont on the Hudson; in 1808 some businessmen from Burlington, Vt, commissioned brothers John and James Winans of that town to build a steamboat for the run along Lake Champlain and the Rivière Richelieu to Dorchester (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu); in June 1809 the Vermont went into service.

By a notarized contract on 5 June, Molson became the third member and financial backer of a partnership founded by John Jackson, “mechanic,” and John Bruce, “shipbuilder,” who were building a steamboat to carry passengers between Montreal and Quebec. The most surprising technical aspect of this undertaking was the construction of the engine at George Platt’s foundry in Montreal. On 1 Nov. 1809 the Accommodation left Montreal at two o’clock in the afternoon; it reached Quebec 66 hours later, on Saturday, 4 November, at eight in the morning, after 30 hours at anchor in the shallows of Lac Saint-Pierre; the return trip to Montreal up the St Lawrence took seven days. The vessel had regular sailings from June to October 1810, the engine having been made more powerful during the winter. The partnership ended with Molson buying the shares of Bruce and Jackson, who said they could no longer take the substantial losses being incurred. In the mean time, on 7 Sept. 1810, Fulton had proposed to Molson the joining of their two enterprises; the terms of the proposal did not seem sufficiently advantageous to Molson, who took no action. Late in October he left Montreal for England to order a steam-engine for the next ship, the Swiftsure, from the firm of Boulton and Watt. The vessel was under construction in Hart Logan’s shipyard on Rue Monarque in Montreal from August 1811 and it was launched on 20 Aug. 1812.

To diversify his interests Molson had again chosen a sector in which the most recent technological advances had occurred. The brewery had been expanding since 1786, bringing him ever increasing profits, and hence he was able to assume the losses experienced with the Accommodation. He did try to obtain a measure of protection by asking the House of Assembly on 6 Feb. 1811 for a monopoly of steam navigation on the St Lawrence between Montreal and Quebec. His request was put forward by Joseph Papineau and Denis-Benjamin Viger* and granted by the assembly, but was rejected by the Legislative Council. With the outbreak of the War of 1812, however, circumstances would prove extraordinarily favourable to shipping on the St Lawrence. Molson offered his ship to the army for the duration of hostilities, but met with a refusal. The military none the less had to use it occasionally on a commercial basis for transporting troops and their supplies. Molson took part in the war as a lieutenant in the 5th Battalion of Select Embodied Militia. Promoted captain on 25 March 1813, he resigned his commission on 25 November.

Early in 1814 another steam-engine was ordered in England. The Malsham (an archaic form of the name Molson), which was built in Logan’s shipyard as well, was launched in September and went into service immediately. The Lady Sherbrooke was added in 1816 and the New Swiftsure in 1817. With the end of the war between France and Britain and the economic depression of 1815, British immigrants began to arrive at Quebec in growing numbers and to seek transportation up the St Lawrence, towards the Great Lakes, and on the Richelieu and the Ottawa. In 1815 Molson purchased a wharf with all its facilities at Près-de-Ville in Quebec from Robert Christie* and Monique-Olivier Doucet; in 1819 he also bought a house at 16 Rue Saint-Pierre. On 16 Feb. 1816 he had obtained from the Executive Council a 50-year lease on a waterfront lot at Montreal with a renewal option, and he proceeded to put up a wharf. It was located in front of a property he had purchased from Sir John Johnson* on 16 Dec. 1815, on which stood a private residence at the corner of Rue Saint-Paul and Rue Bonsecours; in 1816 Molson added two wings to the building and turned it into the Mansion House Hotel. A wharf at William Henry (Sorel) apparently fitted into this network as did the sizeable commercial activity to obtain on contract the wood for steam, which was to be delivered to the various wharfs up and down the St Lawrence where the ships called. By about 1809, Molson had introduced his sons, John, Thomas, and William, to the manufacturing aspects of his enterprises. On 1 Dec. 1816 he formed the first of a long series of partnerships with them under the name John Molson and Sons [see John Molson Jr]. Having transferred greater responsibilities in his enterprises to his sons, Molson could become active in politics. In March 1816 he was elected to the House of Assembly for Montreal East. Politics were closely interwoven with the fundamental interests of the merchants in Lower Canada. Molson did not attend the 1817 session; he was probably not even in the colony. The 1818 session having begun on 7 January, he presented himself on 2 February to be sworn in and take his seat. In the 1819 session, which was prorogued on 24 April, he participated from the opening till about 20 March. He did not run in the 1820 election.

Molson was an active member of the assembly. All the important issues attracted his attention: trade, public finances, banks and currency, inland shipping, education and health, municipal by-laws, fire protection, regulations for public houses and inns, the House of Industry (of which he was a trustee in 1819, according to Thomas Doige’s directory), and the Montreal Library. Two questions concerned him more directly, the Lachine Canal and the Montreal General Hospital. From 1815 to 1821 he took part in the debate over the construction of the canal, speaking out for a private undertaking and a route that favoured his shipping interests. In January 1819, with the support of the merchants, he presented a petition to the assembly for the establishment of a public hospital in Montreal [see William Caldwell*]. The petition was not accepted by the house because of a procedural error that was declared on 18 March; Molson was still in attendance on 19 and 20 March, but did not appear again. The Montreal General Hospital was founded that same year as a private institution, and the four Molsons contributed to the subscription launched in 1820 to buy a lot on Dorchester Street and put up the building.

Even when not in the assembly, Molson continued to follow events closely. In 1822 the presentation to the House of Commons in London of a plan for the union of Upper and Lower Canada caused a political stir in the colony. In Montreal some eminent businessmen, Molson among them, formed a committee in support of the bill which held a public meeting and collected 1,452 signatures.

The description that Hector Berthelot* gave of Molson in the Montreal newspaper La Patrie in 1885 has often been repeated; on the basis of old people’s recollections going back as far as 1820, he portrayed Molson in blue tuque, wooden shoes, and homespun. His final paragraph, however, has not always been noted: “After he closed his brewery at night, he took off his rustic garb, donned black evening dress and a white waistcoat, and sported a pince-nez on a long ribbon. When he was dressed grandly, Mr Molson behaved like a steamboat owner.” But probably also not kept in mind is Édouard-Zotique Massicotte*’s caution in his introduction to the 1916 edition of Berthelot’s articles that during his lifetime the writer was considered less a historian than a humorist.

At the time Molson was transferring managerial responsibilities in the shipping firm to his eldest son, some financial groups in Montreal (in particular the brothers John* and Thomas Torrance and Horatio Gates*) and at Quebec (John Goudie*, Noah Freer, and James McDouall, among others) were beginning to compete fiercely on the St Lawrence, launching various steamboats. The competition led to over-investment, and then to consolidation of the firms. On 27 April 1822 the St Lawrence Steamboat Company [see William Molson] was created, with assets including six ships, three belonging to the Molsons; its management was handed over to John Molson and Sons, which held 26 of the 44 shares. Rivalry with the Torrances continued for some time, but it was finally resolved by cartel agreements on services, prices, and even co-ownership of certain ships.

Meanwhile the Mansion House Hotel had burned down on 16 March 1821; rebuilt in 1824, the year in which Molson acceded to the rank of worshipful sword bearer in the Provincial Grand Lodge of Lower Canada, it was renamed the Masonic Hall Hotel. Molson became provincial grand master for the district of Montreal and William Henry in 1826. At the end of December 1833, finding himself in opposition to his council on a matter of principle, he resigned. Upon the death of John Richardson* in 1831, the chairmanship of the Montreal General Hospital fell to Molson. When the cornerstone of the part to be named the Richardson Wing was laid, Molson officiated as provincial grand master in a ceremony at which masonic honours were rendered.

In the early 1820s, as the shipping assets had been removed from John Molson and Sons and placed in the St Lawrence Steamboat Company, the family firm had to be reorganized. In addition, Thomas Molson had decided to settle in Kingston, Upper Canada, and his departure entailed another large withdrawal of assets from the firm. An agreement establishing a new John Molson and Sons was made in 1824, to take effect retroactively from 1 Dec. 1823, the date on which the accounts of the former company had been stopped. William Molson took over management of the brewery from Thomas.

In 1825 Molson Sr gave up his residence in the faubourg Québec of Montreal and moved to Belmont Hall, a magnificent house at the corner of Sherbrooke and Saint-Laurent. For some time he had owned Île Saint-Jean and Île Sainte-Marguerite, which form part of the Îles de Boucherville. It was to these islands that his ships returned in the autumn for their winter berths and on them Molson established an estate to which he could withdraw now and then. There he kept a sheep-breeding establishment large enough that the sales of meat to butchers and wool to wholesale merchants appeared in the company accounts. On 10 March 1825 the Theatre Royal company was formed [see Frederick Brown]. The principal shareholder, Molson received 44 shares worth £25 each in return for a property he transferred to it on Rue Saint-Paul.

Although during his term as an assemblyman Molson had taken an interest in the founding of the Bank of Montreal [see John Richardson], he had made no financial commitments. He had offered to put up the bank building on one of his properties, but the board of directors had unanimously turned down his proposal and had decided on 10 Oct. 1817 that the bank would buy a lot and erect a building itself. John Molson Jr was elected to the board of directors in 1824. In the crisis that split the board in 1826 [see Frederick William Ermatinger*] and put Richardson’s group in the minority, Ermatinger gave up his place so that Molson Sr could become president. A short time later John Jr resigned to enable Ermatinger to regain his seat. During the elder Molson’s term of office, which lasted until 1830, the bank had to deal with the liquidation of major fur-trading houses that declared bankruptcy, in particular Maitland, Garden, and Auldjo and the firms linked with the brothers William* and Simon McGillivray. It was Simon who had recommended that Molson be named to succeed William as provincial grand master for the district of Montreal and William Henry, notifying him by a letter sent from London in 1826.

In 1828 John Molson and Sons had its responsibilities narrowed; as the agent of the St Lawrence Steamboat Company it was concerned only with shipping. A new partnership was formed under the name of John and William Molson, bringing together the two Johns and William. John Jr withdrew in April 1829, however, and the association was dissolved; on 30 June a new John and William Molson was founded, which included only Molson Sr and William. On 1 May John Jr had set up Molson, Davies and Company with the brothers George and George Crew Davies; as for William, he went into partnership on 1 May 1830 with his brother-in-law John Thompson Badgley to create Molson and Badgley. Molson Sr acted as financial backer and stood surety for both undertakings. In the mid 1820s, with a workshop attached to the brewery on Rue Sainte-Marie as a basis, Molson had established St Mary’s Foundry, handing it over to William’s management. In 1831, on the eve of the opening of navigation on the Rideau Canal, Molson Sr joined with Peter McGill*, Horatio Gates, and others in forming the Ottawa and Rideau Forwarding Company.

Once more in the early 1830s an important new field for investment was being opened up by technological innovation: the railway. On 14 Nov. 1831, after an earlier petition had been rejected, a group of 74 Montreal businessmen, including Molson, asked the assembly for incorporation as the Company of Proprietors of the Champlain and St Lawrence Railroad; they planned to build the very first railway in either Upper or Lower Canada, from La Prairie to Dorchester [see John Molson Jr]. Molson Sr bought 180 shares in the company, thus becoming the largest shareholder, but he was not named to its initial board of directors, which was formed on 12 Jan. 1835.

It was clear that by now Molson was interested only in investing: “I have retired from any active part in business for some years past,” he wrote to the London bankers Thomas Wilson and Company in 1830. He had run in the 1827 elections in Montreal East but had been defeated. However, Lord Aylmer [Whitworth-Aylmer] called him to the Legislative Council in January 1832, along with Peter McGill. The previous year, upon the death of the man generally considered the dean of the Montreal business community, John Richardson, George Moffatt* had been appointed. The three men focused to such an extent on the same questions and causes that one can truly speak of the Molson–McGill–Moffatt trio. Together they sat on most of the committees for public investment, taxation, and monetary, banking, and financial matters. Their shared opinions and interests were patent in the dissent they voiced in February 1833 on the question of sharing with Upper Canada the customs duties collected at Quebec. They took the opportunity to ask that the counties of Montreal and Vaudreuil be detached from the lower province and annexed to the upper one. Like McGill and Moffatt, Molson belonged to the Constitutional Association of Montreal, even though he was less active in it than his eldest son. During his four years as a legislative councillor, he was even more assiduous than he had been as an assemblyman 15 years before; on 23 Dec. 1835, less than three weeks before his death, he was still taking part in council.

Towards the end of his life, he became interested in the organization of a Unitarian congregation in Montreal, which among its supporters had a great many merchants of New England origin. In 1832 he was one of a group that purchased a lot for which a chapel was planned, but the initiative was set aside for a while when the pastor died.

In 1833 William Molson added a large distillery to the brewery. The following year Thomas left Kingston to rejoin his brother in Montreal. Through a new partnership contract with their father, signed on 21 Feb. 1835 but retroactive to 30 June 1834, they formed John Molson and Company [see William Molson]; once more John Jr did not join the firm.

Molson had lost his wife on 18 March 1829, and in his seventy-second year he was stricken with an illness that swiftly brought about his own death, on 11 Jan. 1836, at his estate on Île Sainte-Marguerite. The newspapers carried quite detailed eulogies, but La Minerve mentioned one of his qualities in a somewhat veiled fashion: “Mr Molson belonged to that small number of Europeans who, coming to settle in Canada, reject all national distinctions; just as he had started his fortune with those born in this land, so he always had a large number of Canadians in his employ, whose loyalty must have helped to ensure his considerable profits.” The funeral took place at Christ Church in Montreal on 14 January, and he was buried in the old cemetery of the faubourg Saint-Laurent. Later his remains were transported with his wife’s to Mount Royal Cemetery, to rest in the impressive mausoleum that their sons put up in 1860. The day after his funeral the board of the Bank of Montreal decided that the directors would go into mourning for 30 days.

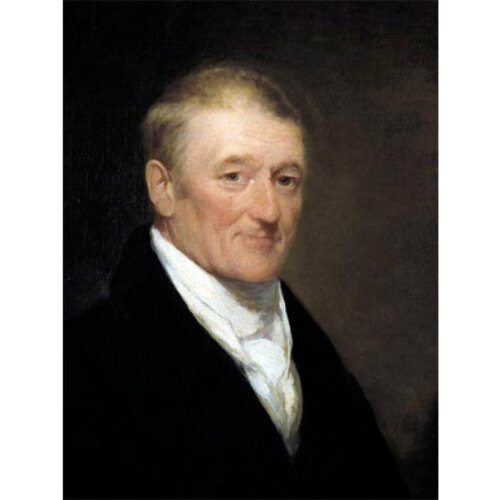

Minutes before his death Molson had dictated his last wishes to notary Henry Griffin, in the presence of Dr Robert Nelson* and Frederick Gundlack. He required his sons to do what they had been incapable of doing during his lifetime: work together in the same enterprises. Each of them, as both residuary legatee and executor of the will, was part owner of the others’ businesses or benefited from the income that these brought in, and each was accountable to his brothers. As the will included some ambiguous parts on which even the notary and the two witnesses could not agree, the brothers instituted legal proceedings against one another, with John on one side and Thomas and William together on the other. At the end of five years they wearied of these disputes and by a strange twist asked the two people whom their father had named in his will to be executors along with them, Peter McGill and George Moffatt (who had both withdrawn), to serve as arbitrators and set the conditions for the division of the assets and income, defining reciprocal rights and obligations. Not until 1843, seven years after their father’s death, did the three brothers truly come to respect his last wishes A portrait of John Molson is in the family’s possession. In a will made on 30 Jan. 1830 he had stipulated: “It is my will that my portrait painted in oil shall be the property of such of my sons and their heirs as shall own the said brewery after my decease.” Perhaps he was seeking to tell posterity which of his numerous enterprises he considered to be the most important; it was the one that had marked his “Commencement on the Grand Stage of the World.”

[John Molson Sr figures quite prominently in each of the three published works on the Molson family. B. K. Sandwell*, The Molson family, etc. (Montreal, 1933), is a serious endeavour, although occasionally too laudatory, which deals almost exclusively with John Molson Sr and his three sons. The work is useful for studying the genealogy of the family. Merrill Denison*, The barley and the stream: the Molson story; a footnote to Canadian history (Toronto, 1955), is a more thorough investigation of the history of the whole family, but too many statements (including dates) are open to question and are not supported (and in some instances are contradicted) by primary sources. S. E. Woods, The Molson saga (Garden City, N.Y., 1983), has been severely criticized by reviewers, and the author’s goal of presenting the inside story of the Molsons has elicited little interest.

Papers relating to the Molsons are to be found principally at PAC, MG 28, III57; vols.1, 10–11, 13, 19, 21, 27–30, 33, and 35 were used in the preparation of this biography. The records of the Montreal Board of Trade (mfm. at PAC, MG 28, III44) and the journal of Jedediah Hubbell Dorwin* (PAC, MG 24, D12) contain references to John Molson. Other materials concerning him are held at the McGill Univ. Libraries, Dept. of Rare Books and Special Coll., CH16.S52, CH330.S290; McCord Museum, M19110, M19113–15, M19117, M19124, and M21228; and ANQ-M, in the minute-books of notaries Isaac Jones Gibb (CN1-175), Jonathan Abraham Gray (CN1-185), and Henry Griffin (CN1-187); Musée du château Ramezay, docs.520 and 523; Bank of Montreal Arch., Court Committee of Directors, minute-books, 1817–36. a.d.]

By-laws of St. Paul’s Lodge, no.514 . . . (Montreal, 1844). Docs. relating to constitutional hist., 1791–1818 (Doughty and McArthur); 1819–28 (Doughty and Story). History and by-laws of Saint Paul’s Lodge, no.374 . . . (Montreal, 1876; 2nd ed., Montreal, 1895). L.C., House of Assembly, Journals, 1816–20; Legislative Council, Journals, 1832–36; Statutes, 1792–1836. Select documents in Canadian economic history, ed. H. A. Innis and A R. M. Lower (2v., Toronto, 1929–33), 2: 140–41, 199–200, 295. “Union proposée entre le Haut et le Bas-Canada,” PAC Rapport, 1897: 33–38. L’Ami du peuple, de l’ordre et des lois, 13 janv. 1836. La Minerve, 14 janv. 1836. Montreal Gazette, 12, 16 Jan. 1836. Morning Courier (Montreal), 14, 21 Jan. 1836. Quebec Gazette, 15 Jan. 1836. F.-J. Audet, Les députés de Montréal, 88–91. Borthwick, Hist. and biog. gazetteer, 34–35, 37–38, 44, 50–51, 53. Joseph Bouchette, The British dominions in North America; or a topographical description of the provinces of Lower and Upper Canada . . . (2v., London, 1832), 1: 431; Description topographique du Bas-Canada, 489–90. Desjardins, Guide parl. Montreal directory, 1820: 20–21, 23, 26, 30, 108. F. D. Adams, A history of Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal (Montreal, 1941). W. H. Atherton, History of the harbour front of Montreal since its discovery by Jacques Cartier in 1535 . . . ([Montreal, 1935]), 3–4; Montreal, 1535–1914 (3v., Montreal and Vancouver, 1914), 2: 138, 271, 275–79, 283, 435, 527, 556, 575–76, 607–8. Hector Berthelot, Montréal, le bon vieux temps, É.-Z. Massicotte, compil. (2v. en 1, Montréal, 1916), 1: 23–25; 2: 11, 18, 53. Campbell, Hist. of Scotch Presbyterian Church, 82–83, 121–24. Christie, Hist. of L.C. (1848–55). François Cinq-Mars, L’avènement du premier chemin de fer au Canada: St-Jean-Laprairie, 1836 (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Qué., 1986), 47–53, 80–86, 91–97, 109–11. G. E. Cone, “Studies in the development of transportation in the Champlain valley to 1876” (ma thesis, Univ. of Vt., Burlington, 1945) J. I. Cooper, History of St George’s Lodge, 1829–1954 (Montreal, 1954). Creighton, Empire of St. Lawrence. Denison, La première banque au Canada, 1: 219–74. Franklin Graham, Histrionic Montreal; annals of the Montreal stage with biographical and critical notices of the plays and players of a century (2nd ed., Montreal, 1902; repr. New York and London, 1969). J. H. Graham, Outlines of the history of freemasonry in the province of Quebec (Montreal, 1892), 168, 170–73, 182. Hochelaga depicta . . . , ed. Newton Bosworth (Montreal, 1839; repr. Toronto, 1974). H. E. MacDermot, A history of the Montreal General Hospital (Montreal, 1950), 4: 2, 4, 12, 34, 41–42, 110. Peter Mathias, The brewing industry in England, 1700–1830 (Cambridge, Eng., 1959). A. J. B. Milbourne, Freemasonry in the province of Quebec, 1759–1959 (n. p., 1960), 72, 75–76, 78–80, 82. Ouellet, Bas-Canada; Hist. économique. S. B. Ryerson, Unequal union: roots of crisis in the Canadas, 1815–1873 (2nd ed., Toronto, 1973). Alfred Sandham, Ville-Marie, or, sketches of Montreal, past and present (Montreal, 1870), 91–93. Maurice Séguin, La “nation canadienne” et l’agriculture (1760–1850): essai d’histoire économique (Trois-Rivières, Qué., 1970). Taft Manning, Revolt of French Canada. G. J. J. Tulchinsky, “The construction of the first Lachine Canal, 1815–1826” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1960); River barons, 14, 25, 51, 111, 213–14, 216–17. G. H. Wilson, “The application of steam to St Lawrence valley navigation, 1809–1840” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., 1961). Owen Klein, “The opening of Montreal’s Theatre Royal, 1825,” Theatre Hist. in Canada (Toronto and Kingston, Ont.), 1 (1980): 24–38.

Cite This Article

Alfred Dubuc, “MOLSON, JOHN (1763-1836) (John Molson Sr),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/molson_john_1763_1836_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/molson_john_1763_1836_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alfred Dubuc |

| Title of Article: | MOLSON, JOHN (1763-1836) (John Molson Sr) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |