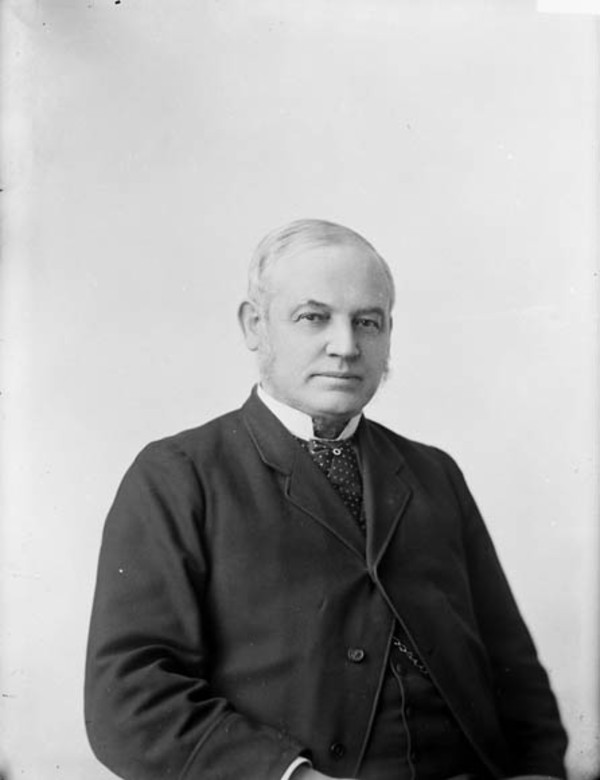

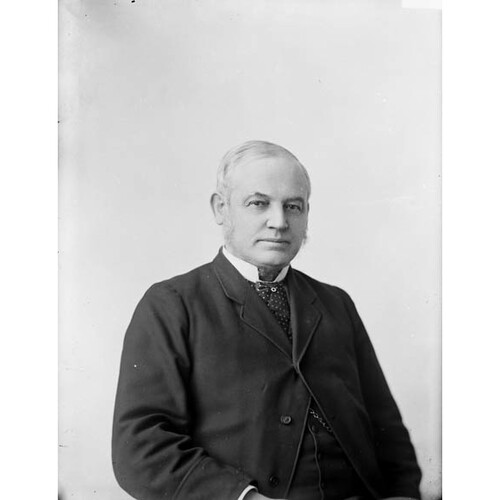

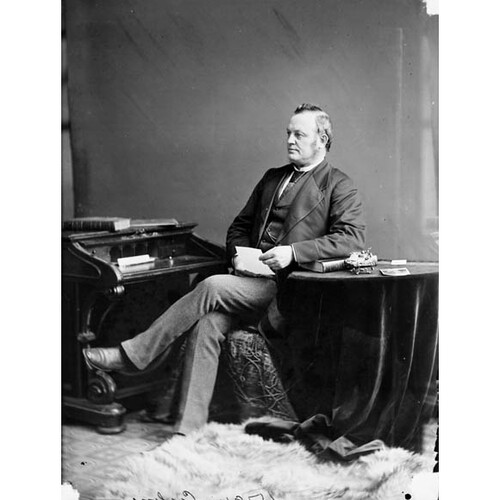

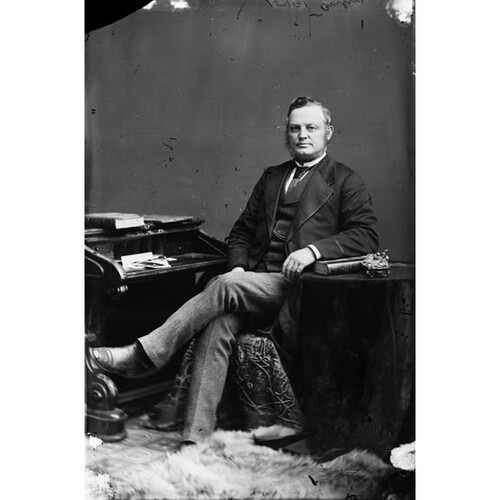

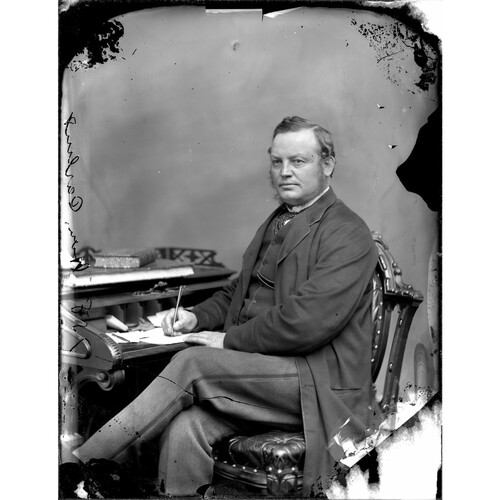

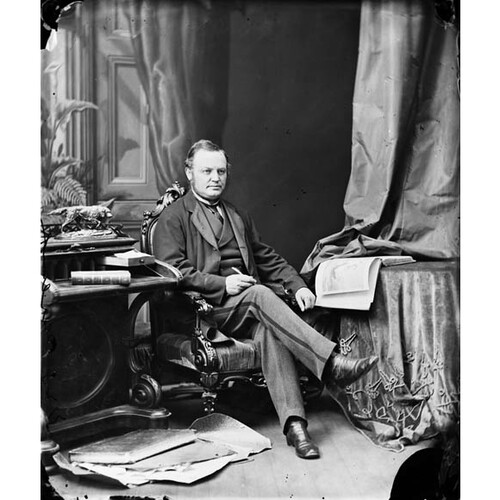

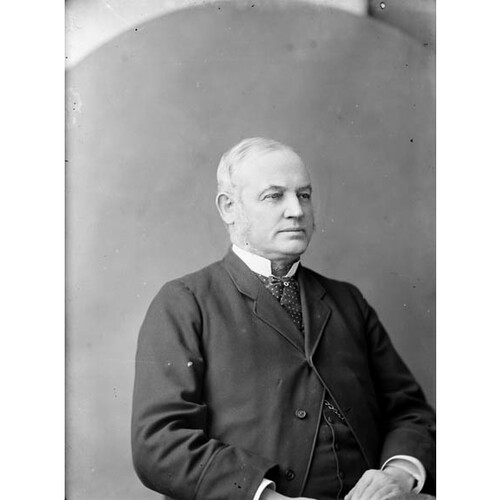

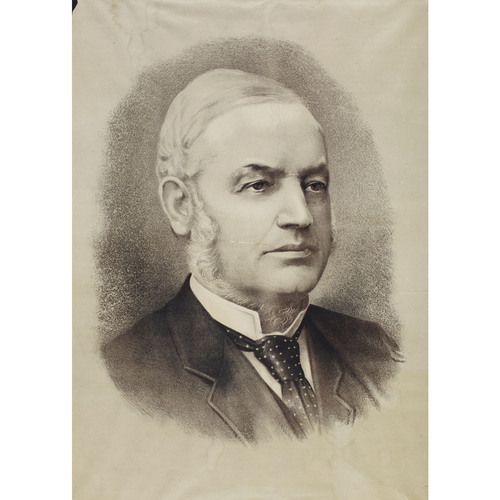

CARLING, Sir JOHN, businessman and politician; b. 23 Jan. 1828 in London Township, Upper Canada, youngest son of Thomas Carling and Margaret Routledge; m. 4 Sept. 1849 Hannah Dalton in London, Upper Canada, and they had four daughters and four sons; d. there 6 Nov. 1911.

John Carling was born and raised on the prosperous farm of his father, where he acquired a reverence for the agrarian way of life. As the three Carling boys approached adolescence, their parents became concerned about the lack of educational opportunity in the township and in 1839 the family relocated in the village of London. John attended the common school there. His parents hoped that he would eventually practise law, but John was not inclined to book learning; he later admitted that he had read only a single book in its entirety.

Carling would be regarded by his daughter Louisa Maria as one of those men “who are natural born contractors . . . at home with large plans and enterprises.” He began his business career by becoming an apprentice at the Hyman and Leonard Tannery in London. Soon he had formed a partnership with his brother Isaac to operate their own tannery in Exeter, some 30 miles away. In 1843 their father opened a brewery in London, producing a beer based on a recipe from his native Yorkshire. The brewery flourished and in 1849 Thomas Carling passed the firm on to his sons William and John. The W. and J. Carling Company was the first of John’s large enterprises and the foundation of his subsequent economic and political success. In addition, he became a large landowner in London and he disposed of various properties for gain. For example, in 1856, for the considerable sum of $8,640, his firm sold the land on which London’s post office would be erected.

A devout capitalist, Carling viewed life in competitive terms: “The game of checkers is like the game of life. Everybody is trying to win and everybody is trying to checkmate him.” He was handsome and affable, and he put these qualities to good use in looking after the public relations of his firm while William handled everyday operations. Carling acquired a reputation for integrity and the epithet Honest John enhanced his business dealings. The brewery fared well and in 1875 Carling’s son Thomas Henry and Joshua D. Dalton entered the business as partners. That same year a new building was opened on the banks of the Thames River. In February 1879 this state-of-the-art structure burned down, and William died of pneumonia contracted while fighting the blaze. John took command of the company’s reconstruction.

The recovery was little short of miraculous. Between 29 April and 29 May 1879 the new plant produced 150,000 gallons of ale, lager, and porter. In 1882 more investors were brought into the enterprise, which became a joint-stock corporation, the Carling Brewing and Malting Company of London Limited. By 1889 it was manufacturing 32,000 barrels of ale, lager, and porter per annum; by 1898 it controlled a “large share” of the Canadian trade. Carling himself never drank beer because it disagreed with his system.

Carling Brewing and Malting was not the only large business enterprise with which Carling was associated. He recognized that its growth depended on an expanding railway network in the London area. Carling’s products were marketed throughout the United States as well as Canada, and massive quantities of barley, malt, and hops had to be brought to the factory. He became a director of the Great Western Railway, a major line in southwest Ontario. His influence with it was evident shortly after confederation when he persuaded the railway to locate its car works in suburban London East, bringing employment to about 300 workmen. Later, when fire destroyed these shops, he used his considerable power within both the federal government and the railway to have them restored, even though there was significant support for their relocation in Brantford. Carling also used his influence to promote the London and Port Stanley Railway and the London and Lake Huron Railway, serving both lines as a director.

There were direct links between Carling’s early entrepreneurial pursuits and his move into politics. He represented Ward 6 on city council in 1855–57 and was a founding member of London’s Board of Trade in 1857. Three years earlier he had impressed two government ministers, in London to work out a land deal with him, with his political and business shrewdness. At a meeting of GWR directors in 1856, the leader of the Liberal-Conservatives, John A. Macdonald*, persuaded Carling to uphold the party standard in London at the next opportunity. In the election of 1857–58 Carling was returned to the Legislative Assembly and he would retain his seat until confederation; in 1862 he served briefly as receiver general in the Macdonald-Cartier ministry.

Thus began Carling’s lengthy parliamentary career and long friendship with Macdonald. Before his initial election, Carling had promised to support the constitutional remedy of representation by population. But when the Grits made a series of “rep by pop” motions in 1861, an embarrassed Carling voted against them. They were, he declared, “mere buscombe motions designed, not to attain the object, but to defeat the Government.” On this occasion loyalty to Macdonald proved stronger than loyalty to principle. Nevertheless, the following year Carling and two other new ministers, John Beverley Robinson* and James Patton, demanded that rep by pop be an open question within the Tory caucus.

Later, Grit leader George Brown* reportedly suggested to Carling on a train ride that he should approach his leader with a proposal for a bipartisan combination dedicated to creating a federal union. The “Great Coalition” eventually resulted from Brown’s initiatives, and in his later years Carling was fond of recollecting their conversation. Though not a Father of Confederation, he might be considered an uncle. His polite manner, coupled with his trustworthy character, often caused him to be cast in an avuncular role. To the extent, however, that he was a political force in the London region, this characterization of him as benign is deceptive. Carling’s brewery, railway investments, and land deals all yielded handsome returns and he undoubtedly used some of the profits to finance his electioneering. Bribes and free drinks were common political tools, and newspaper accounts tell of Tory agents marching prospective voters to the Carling plant just before balloting. It would be naïve to assume that Honest John was not aware of the salient advantage of owning a brewery at election time.

After confederation Carling sat for London in both the dominion and the Ontario legislatures. In John Sandfield Macdonald*’s provincial government of 1867–71 he served as commissioner of agriculture and public works. He had entered the administration at Sir John A. Macdonald’s suggestion and with the government’s defeat in 1871 he was “very glad to get out of office.” Carling was obviously weary of being the peacemaker between the Macdonalds, a function he had assumed mainly out of his regard for the federal leader. When dual representation was abolished in 1872, he stayed in the federal arena. Defeated in 1874, he was re-elected four years later.

In Ottawa London’s mp continued to provide loyal and valuable service to his chieftain. As postmaster general (1882–85) he was responsible for a good deal of the Macdonald government’s patronage. In the House of Commons Carling was quite candid about the political nature of the assignments in his department: “Of course in the appointment of a postmaster the Government’s friends will be consulted as has always been done by hon. gentlemen opposite.”

In carrying out the responsibilities of this office and subsequently as minister of agriculture (1885–92), Carling often deferred to his prime minister. On 22 June 1885, for instance, he eloquently defended the government’s use of subsidies to help the Allan Line of Canadian steamships [see Sir Hugh Allan*] compete with American rivals for transoceanic mail contracts. But once Macdonald intervened in the debate Carling slipped into the background. He emerged at the end to declare: “As the Prime Minister has stated, I think all Canadians are proud of the way the Allan line of steamers is managed.” Carling was, in many respects, an ideal cabinet minister. He was competent and convincing, respected by the opposition, and, above all, generally submissive to the party leader.

It would be wrong, however, to portray Carling as little more than an obsequious follower of Macdonald. He had his own principles and interests to advocate and he consistently did so. Especially prominent on his agenda were the promotion of a progressive brand of conservatism and the advancement of big business, agriculture, and London.

Carling and Macdonald both revered tradition, but they both recognized that it had to accommodate change. As a public school trustee in London (1850–64), Carling had become noteworthy for his support of free public schools. His progressivism was more sharply defined when he entered the Legislative Assembly, where he was committed to the democratic design of rep by pop. By 1866 Carling was arguing further for lower property qualifications for voters and office holders. When, in the first session of the House of Commons in 1867, he pressed for a reduction in the qualifications for Ontario voters in the federal franchise, his liberal stand brought him into brief conflict with his leader. A distressed Macdonald lamely replied that he “did not wish to enter on the discussion of that.”

As Ontario’s first commissioner of agriculture and public works, Carling continued to define his progressive image. The creation of much of the province’s social infrastructure became his responsibility. He directed the construction of the Asylum for the Insane in London (on land he had sold to the government in 1870), the Ontario Institution for the Education and Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb in Belleville, and the Ontario Institution for the Education and Instruction of the Blind in Brantford. Carling appropriated provincial funds for mechanics’ institutes which encouraged working-class Ontarians to develop a variety of self-help plans. Later, as postmaster general, he ensured that an expansion of postal services followed the westward construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. All of these measures were forward-looking, as were many of the changes that Carling introduced in agriculture on the provincial and national levels.

Carling’s progressivism, however, simply modified his essential conservatism, which was reflected in his political support for capitalism and large enterprises. It was only natural that Carling, an important brewer, should defend the interests of big business. In 1863, in the assembly, he strenuously called for an end to the province’s usury laws. They were, he maintained, outmoded and hindered capital formation.

Following confederation Carling became one of the main spokespersons in the federal sphere for capitalism, including his own interests. In the first session of the commons, in 1867, his suggestion that licence fees for brewers be lowered caused conflict with Macdonald and finance minister John Rose*. In parliament Carling constantly defended the interests of the GWR and the other railways with which he was associated. He believed uncritically that such large corporate entities ought to be encouraged by Ottawa and, if necessary, supported by public funds. So, in 1885, he pushed as postmaster general for federal money for the well-established Allan Line to allow it “to build larger vessels and to dispose of those of smaller tonnage.” The creation of bigger and better capitalist enterprises was, for Carling, a high priority. Like Macdonald, he promoted a close alliance between political and economic élites.

Some of the large private enterprises which Carling sponsored in the commons were truly visionary. In 1870, for example, he brought before the house a corporate charter to build a tunnel underneath the Detroit River and thus connect Canada with the United States. This ambitious design would not be fulfilled until 1910. His last major initiative in parliament was also aimed at encouraging business development in the dominion. In 1898 Carling, then a senator, urged the Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier to construct a road between Edmonton and the Yukon so that the intervening territory could be opened to mining interests.

Unlike other members of the corporate élite, Carling did not see a conflict between the interests of capital and those of agriculture. For him, they were complementary, as was the case in the brewing industry. From his youth he had come to love the agrarian lifestyle. He delighted in seeing things grow and later in life he purchased a large farm on the outskirts of London. But farming was more than a hobby. Carling saw it as Canada’s most important economic activity, and some of his most significant and progressive achievements occurred in agriculture.

Carling did much as commissioner of public works and agriculture to promote Ontario’s agrarian sector. Public funds were given to the Fruit Growers’ Association of Ontario, which boosted agriculture in the Niagara area. Through an elaborate drainage scheme a considerable amount of land in the province’s southwestern peninsula was redeemed, especially in the Chatham region. A liberal emigration plan, coupled with generous land grants, helped in the rapid development of the Muskoka district [see Alexander Peter Cockburn*]. In 1870 Carling boasted that “greater advantages” were offered there than in the western United States. Port Carling, on Lake Muskoka, was appropriately named after the minister who did so much to foster the area. The following year he secured funds for the founding of an agricultural college and experimental farm, later established at Guelph [see William Fletcher Clarke*]. When he departed from the provincial scene in 1872 he left behind an impressive record as a friend of agriculture.

Carling’s reputation was enhanced when he served as the federal minister of agriculture, from 1885 to 1892. Seeking to raise the profile of agriculture within the dominion and abroad, he placed Canadian produce on display at international gatherings such as the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London in 1886. Carling is credited with developing, at a time when more and more stock was being imported, the first effective quarantine system to prevent diseased animals from entering the country. He also moved to settle the vast lands in the North-West Territories, just as he had opened up the Muskoka region. Again large land grants were offered and Carling introduced policies to draw settlers. Agents were dispatched overseas, translators were hired to help foreign immigrants, and promotional pamphlets were issued throughout Great Britain and Europe. The depressed economic conditions in Canada were not propitious for a massive influx of homesteaders, but in the late 1890s the Laurier government would use the means initially employed by Carling to populate the prairie region.

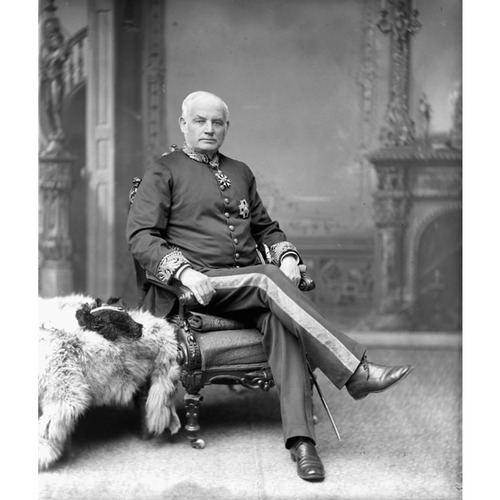

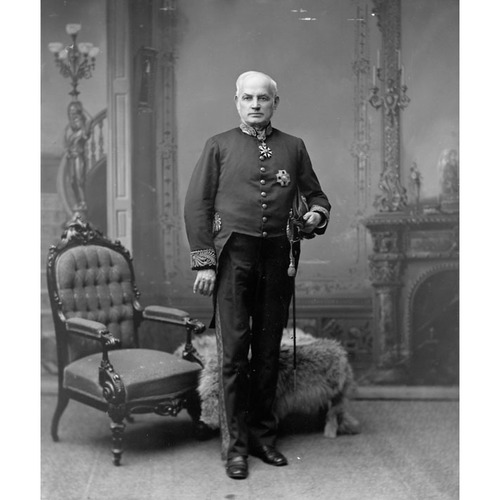

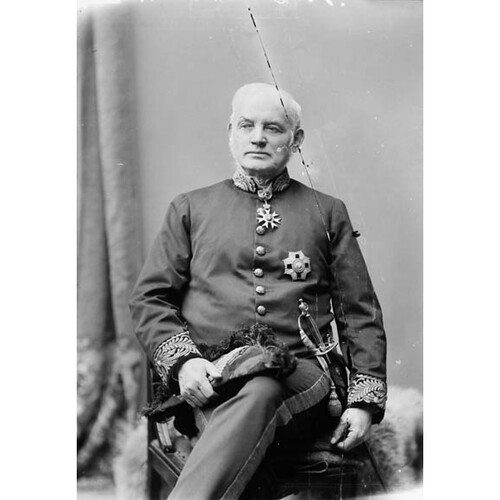

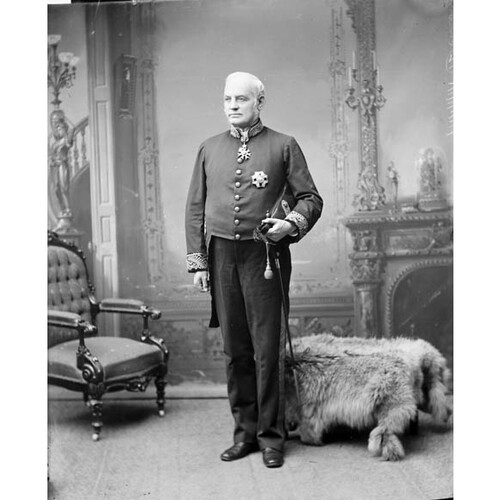

Macdonald’s minister of agriculture was more immediately successful in his formation of a network of experimental farms throughout the dominion. What was to become Carling’s single greatest accomplishment was described by him in the commons when the project was launched in 1886: “It is the intention to establish an experimental farm or station in the neighborhood of the capital. . . . Tests, &c., will be made here of all the different seeds, and experiments made as to the raising of cattle, tree planting and fruit culture, and the analysing of different kinds of artificial manures; and the results of such experiments will be made known by monthly bulletins through the press or otherwise.” Later branch farms were established in Nova Scotia, Manitoba, the North-West Territories, and British Columbia to accommodate regional needs. The program was an instant success, and some far-reaching effects flowed from the research at these government stations [see William Saunders]. In 1893, shortly after Carling had relinquished the agriculture portfolio, Liberals as well as Conservatives on the commons committee on agriculture and colonization joined together in an extraordinary bipartisan gesture to pass a resolution thanking him for his services to the farming community. Later that year, on 3 June, Carling received a kcmg, ostensibly for his assistance to Canada’s farmers.

During his parliamentary career Carling also secured important gains for his home city. He had always viewed service to the community as a public duty. Like many wealthy persons, he regarded philanthropy as an appropriate recompense for his good fortune. In 1859, for example, he had subscribed $100 to a recently created soup-kitchen in London and in 1888 he became a trustee of the Protestant Home for Orphans, Aged, and Friendless. A further contribution to London’s progress came with his election in 1878 as a municipal water commissioner; the next year he oversaw the construction of a structure for the city’s first hydraulic pumps.

Dedicated to bringing government contracts to London, Carling took full advantage of his privileged place within provincial and federal ministries. In 1870 he obtained the incorporation of the insane asylum at Amherstburg into the new regional asylum in London. In 1883, at the federal level, the member for London procured his government’s commitment to establish a military school in his riding. It would be built on property acquired from Carling, whose sense of integrity clearly did not prevent him from profiting at government expense. A federal grant was extended to London’s council in 1886 to help it stage a public exhibition, a project that led to Carling’s sale of additional land to the city. Carling certainly saw to it that London received its fair share of patronage, which aided in turn his repeated re-election. By the 1880s Carling was unquestionably the most powerful political figure in the key Conservative constituency of London.

By the early 1890s, however, this situation had begun to change. Defeated in the general election of 1891, Carling was promptly appointed to the Senate, in April, and thus enabled to continue as minister of agriculture. In February 1892 he resigned from the Senate in order to contest London in a by-election, which he won. That spring Carling refused the lieutenant governorship of Ontario because he and the Tory prime minister, John Joseph Caldwell Abbott* (Macdonald had died in 1891), thought the Liberals might well win the by-election that would have ensued. Later in 1892 Abbott’s successor, Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*, moved to drop Carling from his ministry as part of an attempt to rejuvenate the Tories, who were still reeling from Macdonald’s passing. Even though his popularity in parliament and influence in cabinet had lessened, Carling was stunned.

After prolonged negotiations a face-saving formula was worked out. Carling would receive a knighthood and would remain in the cabinet but without a portfolio. In December 1892 he gave up the agriculture ministry, with which he was so closely linked in the public’s mind. It was rather shabby treatment of a veteran who had faithfully served his party for 35 years. Carling stayed in Thompson’s administration until the latter’s death led to the formation of a new government under Mackenzie Bowell in 1894. Although Carling was re-appointed to the Senate two years later, his political career had effectively ended with the shuffle in 1892. He had little to say in either the commons or the Senate after that humiliating experience.

Sir John spent most of his remaining time in London. He resumed control of his brewery, which had been effectively run during his years in Ottawa by his son Thomas, his eventual successor. In the late 19th century temperance legislation and increased duties on malt caused the London brewer political and commercial discomfort. In public presentations before city council in 1876 over the province’s liquor licensing act, he “spoke in the liquor interest.” By 1895 Carling Brewing had applied to council for a tax reduction to compensate for the “injury” suffered from what industry lobbyist Louis P. Kribs* called the “great teetotal craze.” From his position of semiretirement, Carling fondly recalled the good old days and filled a number of largely honorary positions. In 1899 he became colonel of the 7th Battalion of Fusiliers in London, and in 1904 he was made president of the Ontario Brewers’ and Maltsters’ Association. A Methodist, he was also honorary president of both the Yorkshire Society in Ontario and the Sons of England. He died of pneumonia at his Cedar Grove estate in London on 6 Nov. 1911, and was survived by three sons and three daughters.

Sir John Carling was never a major figure in Canada’s history, but he was significant. He had been instrumental in making his brewery one of the largest in the dominion. In a long career in parliament he served as a direct link between the country’s political and economic élites. During that career Carling consistently fought for a progressive type of conservativism as well as for the interests of big business, the agrarian community, and London.

A 1902 address by Carling, “The pioneers of Middlesex,” was published in the London and Middlesex Hist. Soc., Trans. (London, Ont.), 1 (1902–7): 29–35. Louisa Maria Carling’s reminiscences of her father appear in the London Free Press of 30 Jan., 22 Feb., 8, 29 March, and 23 April 1930.

AO, RG 80-27-1, 16: 242. London Public Library and Art Museum, Hist. ser. scrapbooks, vol.2; London scrapbooks, 2: 7, 53–57; 24: 101–6; 39: 112–15. Mail (Toronto), 2 June 1879. J. L. Payne, “‘Honest John’ Carling the gentlest of men,” Manitoba Free Press, 15 Dec. 1923: 36. F. H. Armstrong, The Forest City: an illustrated history of London, Canada ([Northridge, Calif.], 1986). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1867/68–95; Senate, Debates, 1891, 1896–1911; Royal commission on the liquor traffic in Canada, Report (Ottawa, 1895), 649. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). The Canadian parliament: biographical sketches and photo-engravures of the senators and members of the House of Commons of Canada (Montreal, 1906). Carling, Beverley, Gray, Hildred, West, Mason and their descendants: pioneer families of London Township, Middlesex County; a pictorial, historical and genealogical record, comp. G. P. DeKay (Hyde Park, Ont., 1976). J. C. Dent, The Canadian portrait gallery (4v., Toronto, 1880–81), 4. Directory, London, 1912–13. Alexander Fraser, A history of Ontario: its resources and development (2v., Toronto, 1907), 2. History of the county of Middlesex . . . (Toronto and London, 1889; repr., intro. D. [J.] Brock, Belleville, Ont., 1972). J. [A.] Macdonald, Correspondence of Sir John Macdonald . . . , ed. Joseph Pope (Toronto, 1921); The letters of Sir John A. Macdonald . . . , ed. J. K. Johnson and C. B. Stelmack (2v., Ottawa, 1968–69), 2. Ont., Legislature, “Newspaper Hansard” (AO mfm. of the debates, 1867–1943), 1867–73. “Parliamentary debates” (Canadian Library Assoc. mfm. of the debates of the legislature of the Prov. of Canada and the parliament of Canada, 1846–74), 1858–66. N. Z. Tausky and L. D. DiStefano, Victorian architecture in London and southwestern Ontario: symbols of aspiration (Toronto, 1986). P. B. Waite, Canada, 1874–1896: arduous destiny (Toronto and Montreal, 1971); Man from Halifax.

Cite This Article

Peter E. Paul Dembski, “CARLING, Sir JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carling_john_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carling_john_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter E. Paul Dembski |

| Title of Article: | CARLING, Sir JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |