As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

Source: Link

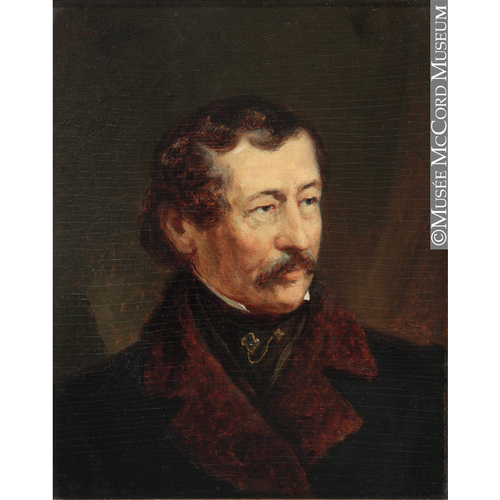

SABREVOIS DE BLEURY, CLÉMENT-CHARLES, lawyer and politician; b. 28 Oct. 1798 at William Henry (Sorel, Que.), youngest son of Clement Sabrevois de Bleury, a soldier, and Amelia Bowers, daughter of a Halifax half-pay officer; d. 15 Sept. 1862 in his manor-house at Saint-Vincent-de-Paul (Laval), near Montreal.

Descended from a military family linked by marriage to Pierre Boucher*, Sieur de Grosbois, Clement-Charles was the last Sabrevois to bear the name Bleury. He spent his childhood at William Henry, where in 1800 and 1801 his father was commandant. He was brought up in a conservative Anglican milieu, where the dominant values were service to the king, parliamentary freedoms, and the interests of empire. From 1809 to 1815 he studied at the Collège de Montreal, then took legal training under his brother-in-law, Basile-Benjamin Trottier Desrivières-Beaubien, and was called to the bar in November 1819. Sabrevois de Bleury soon acquired a reputation as a sound legal practitioner, and won over Montreal’s high society by his charm, elegant manners, and refined style of living. His family background and his skill in arms gained him a commission, on 29 Jan. 1825, as lieutenant in the 3rd Battalion of Montreal militia, and enabled him to rise quickly in the militia. On 24 Nov. 1830 he was promoted captain in the Chasseurs Canadiens; on 22 April 1838 he became a major and on 7 July 1848 he was appointed lieutenant-colonel commanding the Montreal Rifles.

Possibly at the Collège de Montreal, or through regular contact with members of the professions, Sabrevois de Bleury gradually discovered a “Canadian identity” which led him to embrace the Patriotes’ cause. In July 1832, yielding to the party’s pressing requests, he stood as a candidate for the assembly in Richelieu, following the resignation of François-Roch de Saint-Ours. He was then 33, and possessed all he required to win a resounding victory: a distinguished name, a reputation as a brilliant lawyer, the Patriote party’s support. On 8 August he was returned by acclamation. In the house, Sabrevois followed Louis-Joseph Papineau*’s lead. He voted in favour of the expulsion of Dominique Mondelet in 1832 and for the 92 Resolutions in 1834, branding John Neilson* a turncoat because he opposed each of the resolutions. Like many other mhas, Sabrevois de Bleury believed that political strategy by itself could overcome England’s hesitation. But, also like many others, he had to change his view. From 1835 the prospect of armed resistance, the normal outcome of a strategy of “all or nothing,” was taking shape and weakening the bonds of solidarity linking the heterogeneous elements of the Patriote party. The crisis occurred at the opening of the 1835 session, after the reply to the speech from the throne reiterated the party’s firm positions: Sabrevois de Bleury followed the representatives from the Quebec region who rallied to the more moderate Elzéar Bédard*. Disturbed by England’s concessions, and annoyed by the insulting campaign conducted against him in La Minerve and in his constituency by the Montreal radicals, Sabrevois de Bleury in a further step went firmly over to the government side. Twice in 1836 he fought a duel in defence of his honour, which had been scurrilously attacked first by Ludger Duvernay*, the owner of La Minerve, and then by Charles-Ovide Perrault, the Patriote representative for Vaudreuil. The rupture was total and conspicuous. On 6 July 1837 Sabrevois de Bleury agreed to be vice-chairman of a gathering of the governor’s supporters at which George Moffatt presided.

Sabrevois de Bleury was not the stuff of which rebels are made. He was then nearly 40. He had a farm of 416 acres on the banks of the Rivière des Prairies and he liked to retire to the spacious manor-house crowned by his family’s coat of arms which he had built there. He had also inherited part of the seigneury of Boucherville. At Montreal he had an apartment and a law office, and he lived lavishly, riding and fencing, keeping his own carriage, and associating with the last of the French nobility as well as with the important English businessmen who were well on their way up the social ladder. He readily accepted the invitation of the governor, Lord Gosford [Acheson*], to sit on the Legislative Council, serving as a member from 22 Aug. 1837 until its dissolution in 1838.

Sabrevois de Bleury had not been able to identify himself for long with either the habitants or the professional élite. He appeared more at home with Montreal’s British Tories. In April 1837, he, Léon Gosselin, and others had founded Le Populaire, a newspaper promoting moderation and prudence. In that year he commanded the escort that took the political prisoners to the new prison in Montreal. In June 1839 he composed a reply to Papineau, who had attempted to justify his actions in “Histoire de l’insurrection du Canada,” published in the Paris weekly Revue du progrès politique, social et littéraire. Signed Sabrevois de Bleury, the Réfutation de l’écrit de Louis-Joseph Papineau, an indictment of 136 pages, was probably dictated by Sabrevois and drafted by Hyacinthe-Poirier Leblanc de Marconnay, the editor of Le Populaire. In this pamphlet Sabrevois de Bleury developed the argument that Papineau had “prepared, wanted, and even foreseen armed resistance,” and must now accept responsibility for the country’s misfortunes. A well-written piece enlivened with pungent judgements on men and events, this now forgotten pamphlet created a great stir in its day. Scandalmongers asserted that the signatory owed to it his appointment on 20 June 1839 as a member of the new Board of Works, and the following year his nomination by Governor General Sydenham [Thomson*] as alderman for the town council of Montreal, a post he held until 1845, and again in 1847. But the council, which was controlled by the Reform party, refused to choose him as mayor in 1842.

As a supporter of the Montreal Tory party, Sabrevois de Bleury made an ostentatious return to the political scene at the time of the political crisis created by Governor Charles Theophilus Metcalfe*’s personal government. He sided with Denis-Benjamin Viger, and in the elections of November 1844 was returned for the county of Montreal with his friend George Moffatt. But he was not an unconditional government supporter. In 1845 he voted for Allan Napier MacNab as speaker and for Denis-Benjamin Viger’s motion to repeal the clause in the Act of Union forbidding the use of French in the legislature; in 1846, however, he opposed the use of the income from the Jesuit estates for the creation of a system of primary schools, preferring to back the bishops who wanted to use the income to found a university.

Sabrevois de Bleury soon realized that the support he had given the triumvirate of William Henry Draper*, Viger, and Denis-Benjamin Papineau* had discredited him forever in French circles. In 1847 he settled in his manor-house at Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, launching a programme to enlarge and improve the property. He was not a candidate in the 1847–48 elections. In 1849 he let himself be persuaded by his friend Moffatt to sign the Annexation Manifesto; then in 1854, for an unknown reason, he ran for election in the constituency of Laval, not supporting any party. He suffered the most bitter defeat in Canadian political history – he did not receive a single vote. This staggering blow was the signal for his final retirement from public life.

On 16 Jan. 1823, at Saint-Roch-de-l’Achigan, Sabrevois de Bleury had married Marie-Élisabeth-Alix, daughter of Barthélémy Rocher, a merchant and lieutenant-colonel; they had no children. At his death, sheriff Louis-Tancrède Bouthillier, a nephew by marriage, bought the heavily mortaged manor-house.

[C.-C.] Sabrevois de Bleury, Réfutation de l’écrit de Louis Joseph Papineau, ex-orateur de la chambre d’Assemblée du Bas-Canada, intitulé “Histoire de l’insurrection du Canada,” publiée dans le recueil hebdomadaire “La Revue du progrès,” imprimée à Paris (Montréal, 1839).

Archives judiciaires, Richelieu (Sorel, Qué.), Registre d’état civil, Saint-Pierre (Sorel), 28 oct. 1798. Archives paroissiales, Saint-Roch-de-l’Achigan (Qué.), Registres des baptêmes, mariages et sépultures, 16 janv. 1823. PAC, MG 30, D62, 6, pp.71–186. Le Populaire (Montréal), 10 avril 1837–3 nov. 1838. F.-J. Audet, Les députés de Montréal, 249–75. Monet, Last cannon shot. É.-Z. Massicotte, “Les Sabrevois, Sabrevois de Sermonville et Sabrevois de Bleury,” BRH, XXXI (1925), 133–37, 185–87.

Cite This Article

In Collaboration, “SABREVOIS DE BLEURY, CLÉMENT-CHARLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sabrevois_de_bleury_clement_charles_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sabrevois_de_bleury_clement_charles_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | In Collaboration |

| Title of Article: | SABREVOIS DE BLEURY, CLÉMENT-CHARLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | March 26, 2025 |