Source: Link

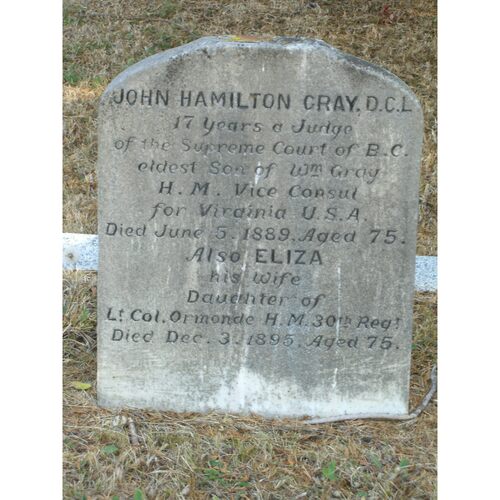

GRAY, JOHN HAMILTON, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. in 1814 at St George, Bermuda; d. 5 June 1889 at Victoria, B.C.

John Hamilton Gray’s paternal grandfather, Joseph, was a loyalist from Boston who settled in Halifax; his father, William, was the naval commissary at Bermuda and later, from 1819 to 1845, the British consul at Norfolk, Va. John Hamilton received a classical education and acquired a ba from King’s College, Windsor, N.S., in 1833. After articling under William Blowers Bliss*, he was admitted as an attorney in New Brunswick on 6 Feb. 1836 and as a barrister on 9 February of the following year. He settled in Saint John and recognition as a successful young advocate followed quickly, largely because of his spectacular courtroom oratory. In 1853 he was created a qc.

After law Gray was most active in the militia. On 25 May 1840 he was appointed a captain in the New Brunswick Regiment of Yeomanry Cavalry. By January 1850 he was a major in the Queen’s New Brunswick Rangers, and on 20 May 1854 he was appointed their lieutenant-colonel, a rank he treasured. Through his military connections he met Lieutenant-Colonel Harry Smith Ormond who commanded the 30th Foot in New Brunswick. After Ormond went to Ireland in December 1843 Gray visited him there, and married his daughter, Elizabeth (Eliza), in Dublin in 1845; they had seven children. Gray’s military interests later led him to membership in the Dominion Rifle Association of which he became vice president.

Perhaps as a result of his close attachment to the military and his family background Gray felt comfortable with the traditional establishment of New Brunswick. A “Conservative of the old school” was the way Liberal newspaperman George Edward Fenety* described him and he meant the phrase to be taken in the best sense. Gray was “very gentlemanly in his manners, and of a forgiving disposition.” His entrance into politics on the Reform side has, however, led to some confusion.

The city of Saint John was dogged by innumerable problems in 1848–49, including economic dislocation related to Britain’s adoption of free trade practices, depression, riots over parades by members of the Orange order, enormous fires, and the rejection of a railway scheme by which it had hoped to gain economic dominance on the northeastern Atlantic seaboard. These difficulties united people of all political leanings in the New Brunswick Colonial Association formed in 1849 [see Charles Simonds*]. At a meeting early in September Gray moved a motion in favour of a “Federal Union of the British North American colonies, preparatory to their immediate independence.” This startling proposal for independence, from the very proper Gray, was rejected by the association, but it anticipated the acceptance of the idea of a federal union; the association also adopted a progressive reform platform which provided the basis for a strong campaign during the 1850 provincial election. Gray and five other Saint John members of the association (Simonds, Robert Duncan Wilmot*, William Johnstone Ritchie*, Samuel Leonard Tilley*, and William Hayden Needham*), all committed to the platform and the defeat of the “compact” government at Fredericton, were elected. Gray apparently was elected as a Liberal, possibly as a radical. He was certainly a Saint John stalwart. In the assembly he proved to be highly effective, moving immediately to the front ranks of the opposition. When he spoke the house was full, for Gray was a orator “of the most finished and classic type.” It was later claimed that he “was perhaps the most polished speaker on the floors of the House, as though he had prepared his speeches over the midnight oil, and set phrases to music . . . his impromptu replies to opponents being of equal polish.”

Lieutenant Governor Edmund Walker Head*, finding his Executive Council inept and moribund, gave its “compact” government one last gasp of life by offering council positions to Wilmot and Gray. They accepted, and the Liberal opposition was robbed of much of its sting. When Wilmot, who was appointed solicitor general, succeeded in his by-election, three of the Saint John members of the New Brunswick Colonial Association, Ritchie, Tilley, and Simonds, saw no course but to resign from the assembly, their cause having been rejected by the people. Fenety later commented that a “terrible bomb-shell was thrown into the Liberal wigwam in St. John” by the Wilmot-Gray defection, and Gray’s conscience bothered him. In a public letter of 2 Aug. 1851 he claimed that he had accepted the offer of a council seat in order to obtain the construction of the European and North American Railway from Saint John to Shediac. It was “distinctly understood that the Government will accept no proposal for building [the Intercolonial to bypass Saint John] which shall not embrace in an equally favourable and explicit manner the European and North American Railway.” Within two years the railway was approved. What Gray did not say was that, being a gentleman who honoured tradition, he could not possibly refuse to serve his governor when asked. Gray’s desertion of his colleagues, however, was to haunt him for the rest of his political career. More and more he came to be regarded as a weathercock with great plumage and little substance.

For the next two decades Gray remained deeply involved in New Brunswick politics. Soon after his entry into office, he became the leader of the Conservatives in the assembly, a role which suited his training and temperament. In 1854 he also chaired a commission of inquiry into the affairs of King’s College, Fredericton, then under threat of abandonment [see Edwin Jacob*], and he valiantly supported the college through its difficult evolution into the University of New Brunswick under president William Brydone Jack. The university thanked him with an honorary degree in 1866.

When the general election of 1854 ended the “compact” government by returning a clear majority of Reformers, Gray found himself leading the opposition to the government of Charles Fisher*. Lieutenant Governor John Henry Thomas Manners-Sutton* disliked his Reform council, and choosing for an issue the controversial prohibitory liquor law of 1855 introduced by Tilley, the provincial secretary, he arbitrarily dismissed them from office in May of the following year, replacing them with a Gray-Wilmot government. The governor had stretched his powers by the action, but Gray, the new attorney general, did not hesitate to accept the office when it was offered. He appeared to be justified when he won a provincial election in June 1856, and he had the liquor law repealed. The temporary nature of the support the Conservatives had garnered from that question became obvious as members drifted back to Fisher. Gray tried to carry on, but he could no longer command a majority in the house and after Fisher’s victory in the elections of May 1857 he resigned and was replaced at the end of that month. Gray had led his last government. He remained clearly identified as a Conservative by opposing a Liberal school bill in 1858 and being dubbed “Archbishop Gray” for his efforts.

Over the next few years Gray’s major contribution was as chairman of three committees of inquiry into the construction of the European and North American Railway, in 1858, 1859, and 1860. Politics, patronage, graft, and spiralling costs had made the railway a natural centre of controversy after it was taken over by the government in 1856. The report of 1858 did point to some irregularities in finance and in awarding of contracts. The second report, in 1859, concluded that the railway would be “a first class Road, of superior description, well and solidly built,” but there was a suggestion that it might have been more cheaply constructed. The final inquiry in 1860 was forced by the Conservatives over Gray’s objections. He declared the railway a “thoroughly constructed road” and condemned his colleagues for their pettiness. During the session of 1860 he dissociated himself from his colleagues and afterwards generally supported Tilley, who became premier in 1861. In the election held that year, however, Gray paid the penalty for political fickleness by being soundly thrashed.

Always in demand as a lawyer, Gray settled back into his practice and also held a number of official posts. From 1857 to 1859 he had been umpire between the fishery commissioners of the United States and Great Britain [see Moses Henry Perley*] acting under the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854, and in 1860–61 he was chairman of the three-man commission, which included Joseph Howe* and John William Ritchie, appointed to investigate the tenant question in Prince Edward Island. In 1864 Gray achieved great popularity in Saint John by defending three New Brunswickers who were among those participating in the seizure of the American steamship Chesapeake during the American Civil War. After depositing passengers and crew at Saint John, the Chesapeake had been captured off Nova Scotia by a Northern cruiser. The leader of the conspirators, John C. Braine, and the three Saint John area men were eventually brought before the New Brunswick courts; Braine, a strong supporter of the Confederacy, was released. Gray, whose brother had been killed while fighting for the Confederacy, successfully defended the other three with the assistance of Ritchie, a Nova Scotian attorney.

Following a short rest after his political defeat in 1861, Gray soon began once again to make his views known. On one occasion, in February 1863, he called for a British North American union in a speech entitled “The practical application of passing events to our country” and on another he pressed for the construction of the Intercolonial Railway, with Saint John as the eastern terminal. Tilley decided to support him even though he was warned that “parties will be in a queer mess . . . ‘Greek meeting Greek.’” Although others had not forgotten the desertion of 1851, Tilley had forgiven Gray. Tilley had also realized that the old political alliances of the 1850s were giving way to new ones, and he began to form a new Liberal-Conservative coalition, with Gray as a member.

Gray won the by-election and was subsequently chosen by Tilley as a New Brunswick delegate to the Charlottetown conference of 1864. As far as can be determined, Gray did not have much influence. He did insist on clearly defined powers for the provinces. “I think it best to define the powers of the Local Governments,” he said at Quebec, “as the public will then see what matters they have reserved for their consideration, with which matters they will be familiar, and so the humbler classes and the less educated will comprehend that their interests are protected.” Gray’s Confederation: or, the political and parliamentary history of Canada (1872), of which only the first volume was published, is little more than a compilation of speeches and newspaper articles of the time, offering no insights into his role or into the success of confederation.

Gray and the other New Brunswickers encountered great hostility when they returned home from Quebec, and in a public meeting Gray’s oratory mysteriously failed him, as he “had not devoted sufficient time to his rehearsals.” Albert James Smith, in the mean time, was leading a crusade against confederation, gaining converts among members of the assembly and the populace. Tilley was in a quandary. He did not believe he could get the Quebec Resolutions through the house, but he was required by law to go to the polls by June of 1865. In January 1865, Gray wrote Tilley that defeat in the assembly was likely. “The chance is too great, and our honour is at stake.” Wait a month for the people to be educated before calling the election, he suggested, “then – Gentlemen, walk the plank.”

Tilley followed that advice and early in March he, Gray, and a majority of the New Brunswick pro-confederates went off the plank together in a landslide anti-confederate victory. Trying to explain what had happened, Gray wrote John A. Macdonald* that the merchants, manufacturers, and intelligent classes had supported them, a point that is ignored by historians who have made the following Gray’s most quoted statement: “Again the Banking interests united against us – they at present have a monopoly and their directors used their influence unsparingly. They dreaded the competition of Canadian Banks coming here and the consequent destruction of that monopoly – and many a businessman now in their power felt it not safe to hazard an active opposition to their influence.” About two weeks later, in a letter to George Brown*, Gray wrote that the people had rejected them “from their hatred to the Govt. and from the desire to oust Tilley who they thought had been too long in power.”

This explanation may be an indication that the relationship with Tilley had cooled, for Gray was not again to play a central role in the confederation movement. He worked hard for the idea, was successful in the 1866 election that reversed the decision of 1865, and served as speaker of the assembly in 1866 and 1867. But he was not invited to the London conference, nor did he gain prominence at Ottawa, though he sat for Westmorland in the House of Commons from 1867 to 1872. Chairman of the committee of supply, he was also appointed dominion arbitrator under section 142 of the British North America Act to settle the division of debts, liabilities, and assets between Quebec and Ontario in 1867. In 1871 he presented a preliminary report on the uniformity of statutory law in Ontario, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. His speeches in the house became infrequent, but he started with a good one in 1867. It was humorous, literate, and moving. “That to be a Canadian, not in its former limited sense, but in the sense of the new Dominion,” the report of the speech noted, “was to belong to a country of which any man might be proud. This national sentiment must be fostered, must be encouraged. He was an Englishman in every fibre of his frame, and every pulsation of his heart. He loved England still, but he loved Canada more.”

Gray realized in 1872 he had no political future and he was not a candidate in the elections held that year. He sought and was granted a puisne judgeship in the Supreme Court of British Columbia on 3 July 1872, an appointment resented in that province where George Anthony Walkem* referred to Gray as an “empty-headed favourite.” Gray none the less served his term with great distinction, providing a balance and specialized skills that would otherwise have been lacking. As late as 1883, however, Attorney General John Roland Hett accused Gray in the Victoria Daily Standard of being in collusion with counsel during a hearing on an election which Hett had recently lost. Gray was vindicated in the courts.

As a judge Gray was to become involved in two controversial subjects, the treatment of the Chinese and the boundary between British Columbia and Alaska. Discrimination against the Chinese in British Columbia began shortly after the arrival of the first immigrants in the 1850s. In 1878 Gray ruled in Tai Sing v. Maguire that the intention of the provincial Chinese Tax Act, 1878, was to “drive the Chinese from the country, thus interfering at once with the authority reserved to the Dominion Parliament as to the regulation of the trade and commerce, the rights of aliens, and the treaties of the empire.” The act, according to Gray, was “unconstitutional and void.” Undoubtedly this decision led to his appointment on 4 July 1884, along with Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau*, as a commissioner on the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration. Their report identified three “phases of opinion” in the province: the first, “of a well meaning, but strongly prejudiced minority, whom nothing but absolute exclusion will satisfy”; the second, “an intelligent minority, who conceive that no legislation whatever is necessary – that, as in all business transactions, the rule of supply and demand will apply and the matter regulate itself in the ordinary course of events”; and the third “of a large majority, who think there should be a moderate restriction, based upon police, financial and sanitary principles, sustained and enforced by stringent local regulation for cleanliness and the preservation of health.” Though Gray appeared personally to support the second opinion, he recommended the third.

Gray also became an authority on the boundary problems between British Columbia and Alaska. In 1876 his involvement in a case in which a prisoner, Peter Martin, had been transported over contested territory led to a diplomatic incident and to Gray’s writing Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie* with recommendations for a solution to the jurisdictional question. His suggestions, in time, became the cornerstone of the Canadian position. In 1884 he wrote a paper on the limits of the Canadian claim, which was officially adopted by the province. Though Gray’s contentions would eventually be repudiated by the Alaskan Boundary Tribunal of 1903, he was so highly regarded that a Canadian delegation at Washington in 1888 to try to settle the dispute postponed its deliberations until he could join them.

Gray actively publicized his opinions on the boundary question and other issues through lectures and articles in magazines and journals. One subject that interested him intensely was the controversy surrounding the Bering Sea seal-fishery. Another was the Imperial Federation League and he helped to organize a local branch of the movement in British Columbia. In 1889, when he was planning to receive Tilley, his old New Brunswick colleague, for whom he had promised “a right Royal Reception” in Victoria, he was struck by paralysis and died on 5 June. His wife, Eliza, unfortunately was left no inheritance.

Gray had several careers, as lawyer, politician, judge, and arbitrator. That he was an excellent lawyer is unquestioned, yet it is as a New Brunswick politician that he is remembered, despite his limited accomplishments. Usually overlooked are his activities as a jurist and negotiator, in which he made significant contributions.

[Though John Hamilton Gray was a renowned orator and leading figure in New Brunswick politics for two decades, he has not as yet attracted a biographer nor did he leave any private papers to encourage one. His short and undistinguished stint as head of the government offered little in the way of substance and his grand speeches have suffered with the passage of time. As a father of confederation he has received token piety, but his Confederation; or, the political and parliamentary history of Canada, from the conference at Quebec, in October, 1864, to the admission of British Columbia, in July, 1871 (Toronto, 1872) is a disappointing collection of speeches and newspaper articles that offers no insights into either his role in the movement or the nature of the problems. One of his reports for the House of Commons was published separately as Extracts from the Hon. J. H. Gray’s preliminary report on the statutory laws: Ontario, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia (Ottawa, 1871), and for his work on the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration see its Report (Ottawa, 1885). Speeches delivered by Gray were published in the newspapers of the day and as pamphlets.

Despite his imposing manner, Gray ranked well below Edward Barron Chandler*, Charles Fisher, and Samuel Leonard Tilley in influence. Since he was a long-time associate of Tilley’s, there are many Gray letters in N.B. Museum, Tilley family papers, and in PAC, MG 27, I, D15 (S. L. Tilley papers), as well as in PAC, MG 26, A (John A. Macdonald papers), and B (Alexander Mackenzie papers). With the exception of one letter, J. H. Gray to W. H. Gray, 5 July 1848, there is no correspondence by him in PAC, MG 24, D63 (Gray family papers).

In the secondary literature George Edward Fenety and James Hannay*, the Whiggish newspaper-historians of the era, both condemned Gray as shallow and opportunistic because of his desertion of the Liberal cause in 1851, though Fenety came to respect him as a gentleman, as can be seen in his “Political notes,” published in Progress (Saint John, N.B.), 1894. More recently, historians of New Brunswick, such as William Stewart MacNutt*, have pictured Gray as a bit player in an imperial pageant. MacNutt’s New Brunswick stands out as having largely superseded all previous studies, especially that of Hannay, Hist. of N.B. MacNutt had written a preliminary draft biography of Gray for the DCB shortly before his death, but he was unable to complete it. In it he empathized with Gray’s gentlemanliness, his conservatism, and his deference. c. m. w.]

PAC, MG 24, B40. PANB, RG 2, RS 6, 1851–67. PRO, CO 188; CO 189. UNBL, MG H12a. B.C., Legislative Assembly, Sessional papers, 1885, “Alaska boundary question . . . .” Documents on the confederation of British North America: a compilation based on Sir Joseph Pope’s confederation documents supplemented by other official material, ed. G. P. Browne (Toronto and Montreal, 1969). G. E. Fenety, Political notes and observations; or, a glance at the leading measures that have been introduced and discussed in the House of Assembly of New Brunswick . . . (Fredericton, 1867). [J. H. Gray], “Mr. Justice Gray to the Hon. A. Mackenzie,” Alaskan Boundary Tribunal, Proc. (7v. and 3v. atlas, Washington, 1904), III: 256–58. N.B., House of Assembly, Journal, 1860–67; Reports of the debates, 1850–67. “Parl. debates” (CLA mfm. project of parl. debates, 1846–74), 1867–72. Tai Sing v. Maguire (1867–89), 1 B.C.R. (part 1), 101. Daily Colonist (Victoria), 6 June 1889. Daily Sun (Saint John), 7 June 1889. Morning Freeman (Saint John), 1860–72. Morning News (Saint John), 1849–72. Morning Telegraph (Saint John), 1864–69. New Brunswick Courier, 2 Aug. 1851. St. John Daily Telegraph and Morning Journal (Saint John), 1869–72. Saint John Globe, 1858–72. CPC, 1867–72. New-Brunswick almanac, 1851. Wallace, Macmillan dict. J. K. Chapman, The career of Arthur Hamilton Gordon, first Lord Stanmore, 1829–1912 (Toronto, 1964). M. O. Hammond, Confederation and its leaders (Toronto, 1917). D. G. G. Kerr, Sir Edmund Head, a scholarly governor ([Toronto], 1954). Ormsby, British Columbia. E. O. S. Scholefield and F. W. Howay, British Columbia from the earliest times to the present (4v., Vancouver, 1914), III: 932–35, 986–90. L. B. Shippee, Canadian-American relations, 1849–1874 (New Haven, Conn., and Toronto, 1939). C. C. Tansill, Canadian-American relations, 1875–1911 (New Haven and Toronto, 1943). Waite, Life and times of confederation. C. M. Wallace, “Sir Leonard Tilley: a political biography” (phd thesis, Univ. of Alberta, Edmonton, 1972). H. C. Wilkinson, Bermuda from sail to steam: the history of the island from 1784 to 1901 (2v., London, 1973). D. R. Williams, ‘. . . The man for a new country’: Sir Matthew Baillie Begbie (Sidney, B.C., 1977). R. W. Winks, Canada and the United States: the Civil War years (Baltimore, Md., 1960). A. G. Bailey, “The basis and persistence of opposition to confederation in New Brunswick,” CHR, 23 (1942): 374–97. Georgiana Ball, “The Peter Martin case and the provisional settlement of the Stikine boundary,” BC Studies, 10 (summer 1971): 35–55. C. M. Wallace, “Saint John boosters and the railroads in mid-nineteenth century,” Acadiensis, 6 (1976–77), no.1: 71–91.

Cite This Article

C. M. Wallace, “GRAY, JOHN HAMILTON (1814-89),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gray_john_hamilton_1814_89_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gray_john_hamilton_1814_89_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | C. M. Wallace |

| Title of Article: | GRAY, JOHN HAMILTON (1814-89) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |