Source: Link

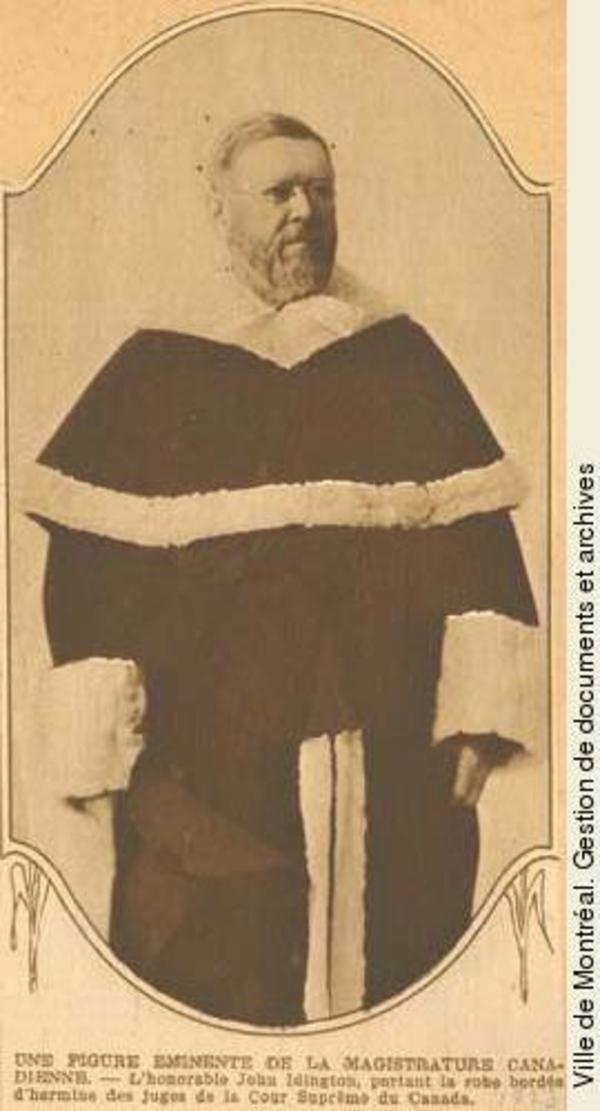

IDINGTON, JOHN, lawyer and judge; b. 14 Oct. 1840 in Puslinch Township, Upper Canada, eldest child of Peter Idington, a farmer, and Catherine Stewart; m. 25 Sept. 1866 Margaret Colcleugh in Mount Forest, Upper Canada, and they had 11 children; d. 7 Feb. 1928 in Ottawa.

John Idington’s parents were among the Scottish pioneers of Puslinch, south of Guelph. The family moved to a farm in Waterloo County near Fisher’s Mills in 1853. An able student, John received a thorough education at William Tassie*’s school in Galt (Cambridge). In 1864 he graduated from the University of Toronto with an llb, was called to the bar, and started practice in Stratford with Robert MacFarlane, the mla for Perth and a fellow Liberal. MacFarlane’s death in 1872 left Idington with a large practice in a community that was expanding rapidly, partly as a result of the location there of the Grand Trunk Railway shops in 1871. He was created a provincial qc in 1876 and a dominion qc in 1885. In 1879, the year he became crown attorney and clerk of the peace for Perth County, he began construction of a substantial brick office building, a sure sign of his success.

A key supporter of Stratford’s incorporation as a city in March 1885, Idington delivered the main oration at a great banquet celebrating the event on 22 July. By this time he had also gained notoriety for his attempt, as a parent and school trustee, to discredit the principal who had set one of his sons back a grade. Other trustees distanced themselves, but Idington persisted, to the point of involving the minister of education, George William Ross*. The vendetta revealed Idington’s stubborn determination and willingness to stand alone. On 18 Jan. 1886 he became the city’s solicitor, a post he would hold until his appointment to the bench; the following year he was elected first president of the Perth County Law Society. From 1891 to 1904 he was a bencher of the Law Society of Upper Canada, and in 1894-95 he was president of the Western Bar Association. Among the benchers, Idington was an early supporter of Clara Brett Martin; his motion of 13 Sept. 1892 would have led to her admission as the first female member of the society but it was rejected by a vote of 9 to 4.

As city solicitor and crown attorney, Idington gained wide experience. In 1891 ratepayers from Stratford’s Romeo Ward presented him with a gold-headed cane as thanks for obtaining the conviction of a woman who ran a brothel. He prosecuted as well in a number of notable murder trials, including that in 1894 of Amédée (Almeda) Chattelle, who had brutally slain and carved up a young girl. Over the years Idington had a number of partners in private practice but each moved on, indicating perhaps that he was difficult to work with.

In March 1904 the Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier* appointed Idington to the provincial High Court of Justice in Toronto. Less than 11 months later, on 10 Feb. 1905, he was elevated to the Supreme Court of Canada. Lawyers have been appointed directly from practice, but no sitting judge has received such quick promotion. An excellent judicial record could hardly be the explanation – Idington had had little time to prove himself. The Canada Law Journal (Toronto) probably reflected the true reason: “Having so recently severed his connection with his former place of abode at Stratford, he naturally would have less hesitation in going to Ottawa than many others.” This explanation suggests that the court did not enjoy sufficient prestige to compensate for the inconvenience of a move to the national capital. At the time the court was not, in fact, “supreme”: its judgements could be appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in England; important cases could go straight there from provincial appellate courts, some of which were felt to be as strong as the Supreme Court; and it was experiencing a high turnover of justices. Moreover, in 1905 Ottawa lacked a large legal fraternity and the amenities of bigger cities.

On the bench Idington displayed industry and marked individuality, and became known for his wit. He rendered dissenting opinions in a great many cases – more than any other judge to the present time. Although legal scholar Ian Bushnell regards him simply as a renegade whose judgements had a “discordant quality,” several of his dissents have merit as important interpretations of fundamental functions and rights in law and government. In 1910, for instance, the Laurier government asked the Supreme Court to determine whether the parliament of Canada could impose on the court the duty to answer reference questions not related to actual or intended federal legislation. The majority of judges said parliament could do so; dissenting, Idington addressed a core issue, the imposition of political function: “If we degrade this court by imposing upon it duties that cannot be held judicial but merely advisory . . . , we destroy a fundamental principle of our government.” Moreover, since provincial and private rights could be affected by a reference, he contended that it amounted to taking away rights without the due process of law.

In Quong-Wing v. the King (1914) the court tested the validity of a Saskatchewan statute that prohibited the employment of white females in businesses owned or managed by an “Oriental person.” Born in China but a naturalized British subject, Quong Wing operated a restaurant in Moose Jaw and employed two white waitresses. His conviction was appealed to the Supreme Court, which, as precedents, had to consider conflicting decisions of the JCPC. In Union Colliery Company of British Columbia v. Bryden (1899) it had held invalid a British Columbia statute prohibiting the employment of Chinese in coalmines because the law infringed federal power over aliens and naturalized citizens [see John Bryden*]. In Cunningham v. Tomey Homma (1903), however, it upheld British Columbia’s Provincial Elections Act, which prohibited any “Chinaman, Japanese, or Indian” from voting. The majority of the Supreme Court followed Tomey Homma. Incensed by the discriminatory legislation, Idington disagreed, stating that “equal freedom and equal opportunity before the law . . . are not to be impaired by the whims of a legislature” and that the “legislation is but a piece of the product of the mode of thought that begot and maintained slavery.” From parliament’s jurisdiction over aliens and naturalization, Idington inferred the power to guarantee equality for naturalized subjects. Historian James W. St G. Walker has written that “if Idington’s implied Bill of Rights was too radical, Bryden was available to squelch a law that was openly discriminatory.” Few judges have their dissenting judgements favourably commended as progressive after the lapse of more than 80 years.

In 1917, during wartime, the Military Service Act instituted conscription and established exemptions, one being for farm workers. As the need for troops increased, the cabinet, acting under the War Measures Act, passed orders in council in April 1918 purporting to cancel these exemptions. George Edwin Gray, a northern Ontario farmer, refused to report for duty; when arrested, he brought a writ of habeas corpus. The issue, as it came before the Supreme Court in July, was whether the government could amend a statute through order in council under the War Measures Act. Four of the six judges upheld such delegation of legislative power. In objecting, Idington stated that “a wholesale surrender of the will of the people to any autocratic power is exactly what we are fighting against.” His opinion is echoed in the work of modern-day constitutional expert Peter W. Hogg: if the War Measures Act is not “unconstitutional abdication . . . it is not easy to imagine the kind of delegation that would be unconstitutional.”

In many constitutional cases Idington tended to take a strong provincialist position. In Re Board of Commerce (1920) the court split on the validity of federal legislation to control prices, with the issue being whether such control fell within federal competence under the “trade and commerce” power of the British North America Act or within provincial competence under “property and civil rights.” Idington, who along with Lyman Poore Duff* and Louis-Philippe Brodeur held the legislation invalid, said: “Our Confederation Act was not intended to be a mere sham, but an instrument of government intended to assign to the provincial legislatures some absolute rights, and of these none were supposed to be more precious than those over property and civil rights.” In his dislike of many forms of regulation, he revealed himself as a laissez-faire liberal. Duff later remarked on his passion for justice; jurist Eugene Lafleur, who frequently appeared before Idington in court, noted that the depth of his convictions made him almost a terrifying figure to counsel who supported what he believed to be the weaker cause.

With the appointment of Sir Louis Henry Davies as chief justice on 23 Oct. 1918, Idington became the senior puisne judge. On 11 Aug. 1921, with the chief in Britain, he administered the oath of office to Governor General Lord Byng*. After trying to persuade Lafleur to accept the chief justiceship following Davies’s death in 1924, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King* appointed Francis Alexander Anglin*, passing over the more senior Idington and Duff. In his diary King wrote that “Idington will be disappointed not being made C.J. but he is 86 years of age and senile.” He was, in fact, approaching 84; whether he was disappointed or not, Duff certainly was.

In 1926 Minister of Justice Ernest Lapointe* asked for Idington’s resignation since he had been absent from the court for extended periods in 1925 and 1926. Whatever his reply, he clung to office. The Liberal government had been considering mandatory retirement for judges of the Supreme and Exchequer courts, and Idington’s refusal to go provided the catalyst. Legislation was enacted, effective 31 March 1927, requiring retirement at age 75. Idington was thus forced to step down that day. On 5 October his wife passed away and four months later he died, leaving a modest estate of $41,842. Survived by four sons and four daughters, he was buried in Avondale Cemetery in Stratford.

AO, RG 80-27-2, 79: 183. Beacon Herald (Stratford, Ont.), 14 April 1956, 3 July 1971, 26 Aug. 1978, 17 July 1982. Globe, 6 Oct. 1927, 8 Feb. 1928. Guelph Mercury (Guelph, Ont.), 11 Oct. 1866. Ian Bushnell, The captive court: a study of the Supreme Court of Canada (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1992). Canada Law Journal (Toronto), 40 (1904): 209; 41 (1905): 206-7. Canadian Bar Rev. (Toronto), 6 (1928): 142-43. Canadian Law Times (Toronto), 24 (1904): 114-15; 25 (1905): 164. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). W. A. Craik, “Canada’s Supreme Court at work,” Maclean’s (Toronto), 27 (1913-14), no.5: 13-16, 137-38. Cunningham v. Tomey Homma, [1903] Law Reports, Appeal Cases (London): 151-57 (Privy Council). J. G. Hodgins, The Stratford case: Idington vs. McBride; report of the commissioner . . . (Toronto, 1887). P. W. Hogg, Constitutional law of Canada (4th ed., Scarborough [Toronto], 1997). William Johnston, History of the county of Perth from 1825 to 1902 (Stratford, 1903; repr. 1976). W. L. M. King, The Mackenzie King diaries, 1893-1931 (microfiche ed., Toronto, 1973), 12 Sept. 1924. Adelaide Leitch, Floodtides of fortune: the story of Stratford and the progress of the city through two centuries (Stratford, 1980). Quong-Wing v. the King (1914), Canada Supreme Court Reports, 49: 440-69; Re George Edwin Gray (1918), 57: 150-83. Re Board of Commerce (1920), Canada Supreme Court Reports (Ottawa), 60: 456-522; Re marriage laws (1912), 46: 132-456; Re references by the governor-general in council (1910), 43: 536-94. Saturday Night, 18 Feb. 1928: 2. J. G. Snell and Frederick Vaughan, The Supreme Court of Canada: history of the institution ([Toronto], 1985). Union Colliery Company of British Columbia v. Bryden, [1899] Law Reports, Appeal Cases: 580-88. J. W. St G. Walker, “Race,” rights and the law in the Supreme Court of Canada: historical case studies ([Toronto and Waterloo, Ont.], 1997). Waterloo Hist. Soc., Annual report (Kitchener, Ont.), 1 (1913): 38.

Cite This Article

Gordon Bale, “IDINGTON, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/idington_john_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/idington_john_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gordon Bale |

| Title of Article: | IDINGTON, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |