Source: Link

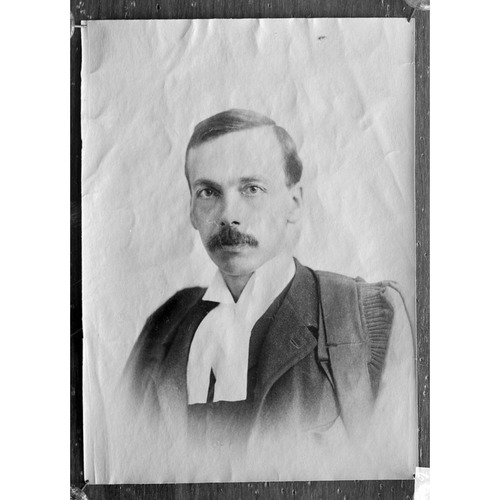

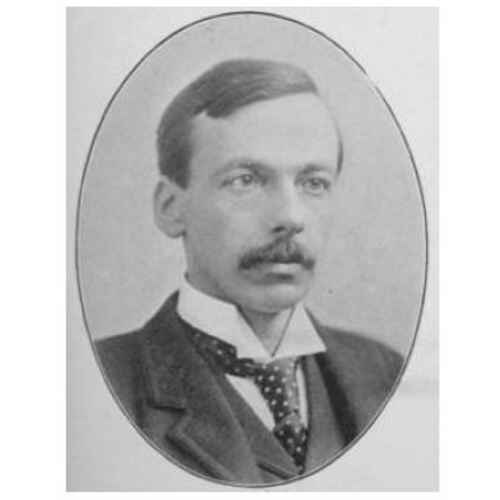

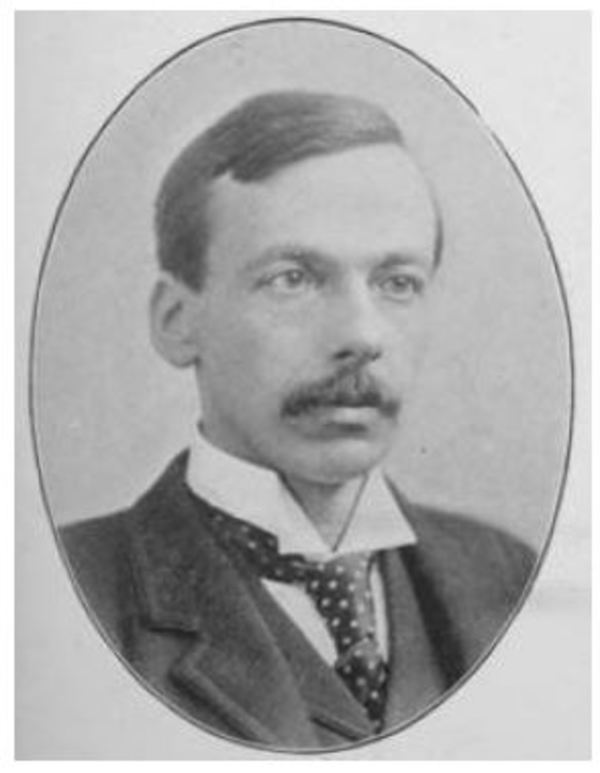

LAFLEUR, EUGENE, lawyer and university professor; b. 12 April 1856 in Longueuil, Lower Canada, eldest son of the Reverend Theodore Lafleur and Adele Voruz; m. 16 March 1896 a first cousin, Marie-Alice Voruz, in Geneva, Switzerland, and they had two sons and two daughters; d. 29 April 1930 in Ottawa.

Eugene Lafleur was of Swiss lineage on his mother’s side of the family. His father’s ancestors, of Swiss or French origin, had settled in New France before 1700. Lafleur was raised a Baptist, but in adulthood he joined the Church of England. His father, an influential member of the Grande-Ligne mission [see Henriette Odin*], ministered in Longueuil and then in the Eastern Townships before moving his family to Montreal when Eugene was 14. Although raised in an English-speaking household, Lafleur was markedly proficient in French. He enrolled in the classical program of the High School of Montreal in 1870 and became an outstanding student. After graduation he entered McGill College, took his ba in 1877 at age 21, and was graduated bcl in 1880, winning the gold medal for the highest standing in mental and moral philosophy. He was called to the bar of the province of Quebec the following year. Thus began an illustrious career that would last nearly 50 years. He served as a bencher of the Quebec bar between 1894 and 1897, was created qc in 1899, became bâtonnier of the Montreal bar and of the province in 1905-6, and was the acknowledged leader of the legal profession in Canada during the last 20 years of his life.

In 1890 Lafleur had accepted the post of professor of civil law at McGill. He developed a deep interest in conflicts of laws (international disputes between individuals), becoming a Canadian pioneer in the field. His reputation was enhanced by the publication in 1898 of a gracefully written text on the subject, the first by a Canadian author. That same year he became professor of international law and he taught until 1909. He resumed his professorship in 1912 and taught public international law (disputes between nations) until 1921, when he retired. McGill conferred on him an honorary lld in October 1921, and he held the title of emeritus professor of law until 1929. In 1911 he had been appointed chairman of a tribunal of arbitration set up by the United States and Mexico to settle a long-standing dispute between the two nations over ownership of a strategically located piece of land, the Chamizal, at El Paso, Tex., and Juárez, Mexico, left exposed by a shift in the course of the Rio Grande. Lafleur, joined by his Mexican colleague, ruled in favour of Mexico, the American commissioner dissenting.

Lafleur was, however, first and foremost an advocate, pleading clients’ causes in court. In 1885 he had taken a partner and founded the firm that still continues as the Montreal office of McCarthy Tétrault. One of his articled students was Aimé Geoffrion*, another luminary of the bar. Lafleur did mainly trial work in his earlier years, but with age and experience he preferred the appellate courts, where one could dispassionately analyse legal issues. He firmly believed that the role of the advocate was not subservient to that of judges and that bench and bar together should respectfully seek solutions to legal problems. As his reputation widened, he began to confine himself to appeals in the Supreme Court of Canada and the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Probably no other Canadian lawyer to this day appeared in the Supreme Court as often as he did; the published reports show him there on just under 300 cases, but there were many unrecorded appearances during the preliminary stages of appeals. He argued before the Privy Council in London on at least 30 recorded cases and an unknown number of unrecorded occasions.

Although he took cases covering the whole spectrum of law, he achieved a national reputation, primarily as a constitutional lawyer and, secondly, as a lawyer engaged in freight rate litigation. In his time, a constitutional lawyer was concerned with the distribution of legislative powers between the federal and provincial governments set forth in the British North America Act. Although the broad lines of interpretation of the act tended to favour provincial rights when a competing interest with Ottawa was involved, wide areas of jurisdiction were still to be settled as Canada became more and more industrialized. This change in the economy, combined with increasing governmental intrusion into trade and commerce, was reflected in disputes between the provinces and Ottawa about regulatory jurisdiction over such matters as business enterprises and commercial corporations and over the development of water resources for commercial use, a provincial field, as opposed to their use for navigation, a field of federal jurisdiction. The development of water resources was of particular concern to Quebec, to whose governments Lafleur gave advice over many years. The regulation by the Board of Railway Commissioners of rates set by railways moving goods across provincial boundaries and the application of the Crowsnest Pass agreement to grain shipments formed, in Lafleur’s lifetime, the most important commercial litigation in the country. During his last 20 years there was hardly a case of consequence concerning constitutional law or freight rate litigation that did not involve him.

Two prime ministers offered Lafleur judicial appointment. In 1907 Sir Wilfrid Laurier* urged him to accept a seat on the Court of King’s Bench in Quebec, but he declined. In 1924, after the death of Sir Louis Henry Davies, chief justice of Canada, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King* did his utmost to persuade Lafleur to accept the chief justiceship. Again, no inducements could sway Lafleur, whose stated ground of refusal was his age. In reality, Lafleur preferred the life of an advocate; as he told a colleague, he loved “the smell of powder.”

Lafleur’s decision was also prompted in part by financial reasons – he enjoyed a handsome income, far greater than that which he would have earned as chief justice – and by his reluctance to leave Montreal for Ottawa. He lived comfortably in a large house on Rue Peel, where he maintained a horse and stable. Weather permitting, he rode on the slopes of Mount Royal before breakfast. He enjoyed his membership in the University Club in Montreal, of which he was president for 1922-23, and, with friends of like minds, he cultivated literary and theatrical pursuits.

Late in April 1930 he went to Ottawa to put the finishing touches to his submission in an appeal to the Supreme Court. Soon after his arrival he came down with a heavy cold which turned into pneumonia; he died, unexpectedly, on 29 April. After a funeral service at Christ Church Cathedral in Montreal on 2 May, he was buried in Mount Royal Cemetery, in Outremont (Montreal).

Lafleur possessed all the talents which make for a highly competent advocate: a retentive memory, a capacity for sustained concentration, an extensive knowledge of many areas of the law, and the ability to divine the thinking of judges so as to turn them in his clients’ favour. These, and others, are obvious, but he possessed less easily defined skills which lifted him above the level of a superior advocate to that of a great one. He spoke spontaneously in both languages with elegant turns of phrase. When in court he used the briefest of notes, which belied the extent of his underlying preparation. He was invariably courteous to the judiciary and legal opponents alike. He was even-tempered, patient, and thoughtful, free of theatrics and pyrotechnics. There was, over and above even those attributes, a further distinction rooted in his character, an absolute integrity. The Privy Council adverted to this in paying tribute to him in its proceedings on 1 May.

During Lafleur’s time the gap between Roman Catholics and Protestants was far wider and of far greater significance than it is today. Lafleur was an anomaly, a Protestant of foreign background, yet a member of both the French Canadian and the English Canadian establishments. In fact, he was truly bilingual, bilegal, and bicultural, but single-mindedly Canadian.

Eugene Lafleur is the author of The conflict of laws in the province of Quebec (Montreal, 1898) and International law and the present war ([Toronto, 1915?]).

BCA, GR-1323, nos.244/10, 2599/10, 4263/10, 4264/10 (mfm.). McCarthy Tétrault (Montreal), “Clarkson Tétrault Avocats, barristers, and solicitors” (typescript, 1985); Daybook, 1919-29 (fees and drawings); W. J. Henderson, “Recollections” (typescript, 1948); A. K. Hugessen, “Reminiscences” (typescript, 1963); Indenture of clerkship, 16 Jan. 1878; Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, proc., 1 May 1930; W. L. M. King to Eugene Lafleur, 8-9 Sept. 1924 (mfm. at LAC); Opinion books, 1 (1885)-19 (1934); Thomas Shaughnessy, “Clarkson Tétrault” (typescript, 1981); Testimonial, 8 Jan. 1881. LAC, MG 26, J1, 102: 86522 (mfm.); J13, 4-5, 11 mai, 12 sept. 1924. Private arch., R. E. Parsons (Montreal), High School of Montreal, reports of the attendance, progress and conduct of Eugene Lafleur, 31 Jan., 15 April 1871; 31 Jan. 1872; letters from the État Civil de la Ville de Genève to Marie-Alice Voruz, 2 mars 1896, and to Eugene Lafleur, 7 mars 1896. Gazette (Montreal), 30 April 1930. Montreal Daily Star, 30 April, 1-3 May 1930. Times (London), 30 April, 1-2 May 1930. Canada Supreme Court Reports (Ottawa), 1890-1930. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Canadian Railway Cases (Toronto), 17 (1913-15): 123-231. Eugène Lafleur: l’homme et l’avocat (Montréal, [1934]). E. A. Forsey, A life on the fringe: the memoirs of Eugene Forsey (Toronto, 1990). Law Reports, Appeal Cases (London), 1900-30. J. E. Mueller, Restless river: international law and the behavior of the Rio Grande (El Paso, Tex., 1975). D. R. Williams, Just lawyers: seven portraits (Toronto, 1995).

Cite This Article

David Ricardo Williams, “LAFLEUR, EUGENE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lafleur_eugene_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lafleur_eugene_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Ricardo Williams |

| Title of Article: | LAFLEUR, EUGENE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 24, 2025 |