Source: Link

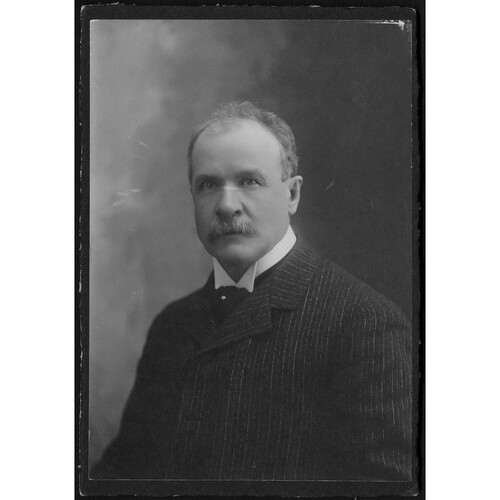

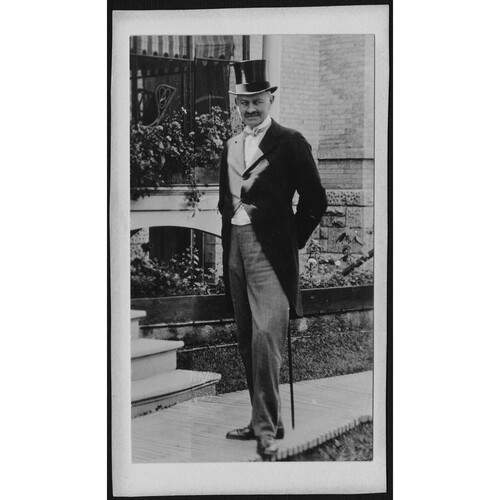

BYNG, JULIAN HEDWORTH GEORGE, 1st Viscount BYNG, militia and army officer, governor general, and police commissioner; b. 11 Sept. 1862 at Wrotham Park, Barnet (London), England, son of George Stevens Byng, 2nd Earl of Strafford, and his second wife, Harriet Elizabeth Cavendish, daughter of Charles Compton Cavendish, 1st Baron Chesham; m. 30 April 1902 Marie Evelyn Moreton (1870–1949) in London; they had no children; d. 6 June 1935 at Thorpe Hall, Thorpe-le-Soken, England, and was buried in nearby Beaumont-cum-Moze.

Julian Byng was born into an aristocratic family with a strong military tradition. John Byng*, a great-great-great uncle, was an admiral in the Royal Navy during the Seven Years’ War, and Sir John Byng, Julian’s grandfather, served as a general in the British army during the Napoleonic Wars. George Stevens Byng was a member of the landed aristocracy but had only modest means to support his 13 children, of whom Julian was the youngest. He was educated at home until 1874, when, at age 12, he entered Eton College. Julian was not a strong student, and in four years there he progressed only to the lower fifth form. (He did acquire a nickname, Bungo, which he would retain all his life.) His father could not afford to purchase a regular army commission for him, and so on 12 Dec. 1879 he became a second lieutenant in the 2nd Middlesex Militia; he was promoted lieutenant on 23 April 1881, by which time the unit had been renamed the 7th Battalion of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. In 1882 the Prince of Wales, a friend of his father, offered Julian a place as a junior officer in his own cavalry regiment, the 10th Hussars, which was then stationed in India. He happily accepted, was commissioned in January 1883, and two months later joined the 10th in Lucknow. It was a very expensive regiment, but Byng managed to supplement his meagre income by purchasing ponies, which he then trained for polo and sold at a profit.

In December 1883, after ten years of service in India, the 10th was ordered home. It sailed from Bombay (Mumbai) on 6 Feb. 1884 but was diverted to the eastern Sudan, where it spent a month suppressing a rebellion against British interests there. Byng was mentioned in dispatches for his actions on 13 March during a fierce battle at Tamai, when he had his horse shot out from under him. The 10th finally reached England the following month and was attached to Aldershot Command, where Byng trained soldiers and new horses. On 20 Oct. 1886 he was appointed adjutant (the staff officer for the commanding officer) and was soon managing the regiment, which was valuable experience for an ambitious young man. On 4 Jan. 1890 Byng was promoted captain, and in 1893–94 he completed a two-year training course at the Staff College in Camberley. He then rejoined the Hussars, now stationed in Ireland, and remained with the unit until it was transferred back to Aldershot in June 1897. Shortly after arriving there, Byng left the 10th to become adjutant of the 1st Cavalry Brigade; soon afterwards, he took up new duties as deputy assistant adjutant-general of Aldershot Command. A year later he was promoted major.

In 1899 Byng was ordered to South Africa after the outbreak of war there. He arrived on 9 November and was given command of a new cavalry regiment of irregular colonials, the South African Light Horse. His men were unused to the discipline of military life but were skilled at working with horses and adaptable to circumstances. Equally adaptable, Byng quickly won their loyalty, and through intense training he moulded them into a regiment of excellent quality. By the summer of 1900, according to biographer Jeffery Williams, “Byng’s coolness under fire had become a legend in the Light Horse and his concern for his men had won their devotion.” Mentioned five times in dispatches, he was made brevet lieutenant-colonel (a promotion without an accompanying pay raise) in November 1900, brevet colonel in February 1902, and full lieutenant-colonel on 11 October of that year.

In March 1902 Byng was given three months’ leave to go home and marry Evelyn Moreton, whom he had met at a dinner in 1897. “The striking and statuesque Evelyn,” Williams writes, “had a sense of adventure and a flair for the unusual.” She was the daughter of Richard Charles Moreton, who had been the assistant marshal of ceremonies to Queen Victoria; as a child she had lived in Ottawa when her father was controller to Governor General Lord Lorne [Campbell*]. Julian and Evelyn were married on 30 April 1902 and, after a holiday in France, they returned to South Africa as the war was ending. Byng was ordered back to England and then to India, where he took command of the 10th Hussars. There, tragedy struck: Evelyn suffered miscarriages that were poorly handled by local doctors, and to the couple’s deep disappointment it became impossible for her to have children. Julian’s right elbow was shattered and dislocated during a polo match in January 1904, and, fearing that the injury might end his military career, he and Evelyn returned to England, where he endured several months of painful recovery.

Over the next decade Byng would proceed through a series of appointments of increased responsibility. In 1904 he established a school for cavalry at Netheravon, and the following year, when he became a full colonel and temporary brigadier-general, he assumed command of the army’s 2nd Cavalry Brigade. From 1907 to 1909 he led the 1st Cavalry Brigade at Aldershot, and on leaving this unit he was promoted major-general on 1 April 1909. On 9 Oct. 1910 he was put in charge of the East Anglian Division of the Territorial Force, which was responsible for the defence of the homeland. The division numbered over 500 officers and more than 17,000 men, all of whom were part-time volunteers, supported by a few regular army staff officers and instructors. The Byngs established a home in Great Dunmow, Essex, where Julian developed friendships with London editors and writers who were his neighbours. He also lent his support to the Boy Scout movement and became the organization’s first commissioner for north Essex.

In May 1912 Byng was made colonel of the 3rd Hussars, and in September he and Evelyn travelled to Cairo, where on 30 October he assumed command of British forces in Egypt. The 5,000-man garrison there, which was charged with the protection of the Suez Canal, consisted of four infantry battalions, a cavalry regiment, two batteries of artillery, and administrative units; Byng also had other soldiers in the eastern Mediterranean under his command, including the garrison in Cyprus. When World War I broke out in early August 1914, he quickly took steps to guard the canal and Egyptian state railways from sabotage, and to intern enemy aliens. On the 12th the secretary of state for war recalled Byng to England to lead the 3rd Cavalry Division, and in early September he and Evelyn sailed for home.

Byng’s division was assigned to the 1st Corps and soon saw action in Belgium at the first battle of Ypres (Ieper), fought in October–November 1914. The 3rd Cavalry was, as historian Cyril Bentham Falls puts it, “repeatedly called upon to restore ugly situations at short notice and in the most unfavourable conditions,” and it gave decisive support to the Allied victory in the battle. In April 1915 Byng took temporary command of the Cavalry Corps, and a month later, during the indecisive second battle of Ypres [see Albert Mountain Horse*; Sir David Watson*], he was made the corps’s regular commander and promoted temporary lieutenant-general. Although he remained outwardly cheerful, Byng was deeply affected by the horrors of modern warfare. In 1935 John Buchan, one of his closest friends, would write, “I have seldom read anything more moving than his letters from the Front in which he spoke of the terrible losses in the battles of Ypres.”

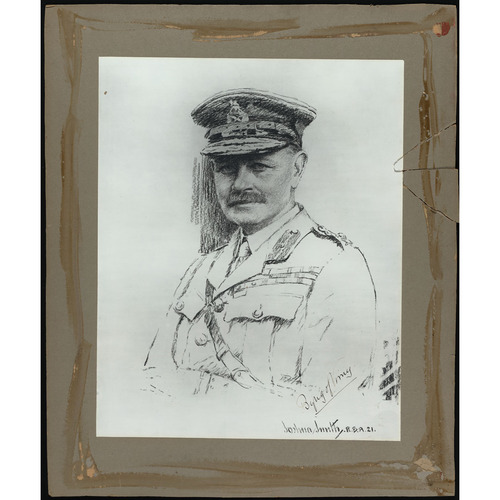

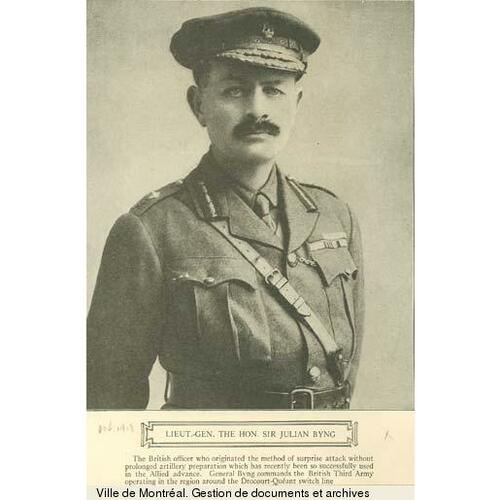

Byng returned to London in July 1915 to receive a kcmg from King George V. A month later he was dispatched to the Gallipoli peninsula to command the 9th Corps there, and he arrived at Suvla Bay (Anafarta Liman) on 24 August. Byng quickly recognized the hopelessness of the British position, and within a week he had directed his staff to prepare plans for an evacuation. When the order to withdraw finally came in early December, the massive and dangerous operation was completed without the loss of men, animals, or equipment. This exercise was a testament to Byng’s leadership, which was characterized by his careful planning and reliance on the precise execution of duties by his troops. “In addition to technical skills,” Williams notes, “his qualities of intellect and character had now become apparent.” In March 1916 Byng was awarded a kcb (dated to 1 January) for his service in Gallipoli, and he spent the next two months in command of the 17th Corps at Vimy Ridge.

In late May 1916 Byng was ordered to replace Lieutenant-General Edwin Alfred Hervey Alderson* as commander of the Canadian Corps. Perplexed by the assignment, Byng wrote to a friend: “Why am I sent to the Canadians? I don’t know a Canadian. Why this stunt? Am rather sorry to leave the old crush as we were fighting like hell & killing Boches. However[,] there it is. I am ordered to these people & will do my best.” The new post, which brought with it a promotion to full-lieutenant general, presented him with unique opportunities and challenges. On the one hand, while divisions in the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) were regularly transferred in and out of various corps, this sort of fluidity was unknown in the Canadian Corps, which had three divisions, soon to be augmented by a fourth, consisting of Canadian troops who were led by both British and Canadian officers. The resulting cohesiveness of the corps would be a major advantage when Byng was preparing his men for battle.

On the other hand, the corps had been the sport of numerous self-styled prominent Canadians, including members of Sir Robert Laird Borden’s Conservative government. Sir Samuel Hughes*, the minister of militia and defence, played a leading role in this activity, chiefly by appointing party supporters who had honorary commissions, rather than actual military experience, to carry out tasks normally conducted by senior members of the corps. Two such individuals were Ontario entrepreneur Honorary Colonel John Wesley Allison, who secured supplies for the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) – and later admitted that he had profited from a shell contract – and Montreal mining promoter Lieutenant-Colonel John Wallace Carson, who became Hughes’s personal representative in charge of procurement for the CEF in the United Kingdom. Chief among the beneficiaries of this unorthodox system, however, was Hughes himself. He fancied himself not just the civilian leader of the Department of Militia and Defence, but also the commander of the CEF overseas. To embellish that affectation, another Hughes crony, Sir William Maxwell Aitken*, took a major part in getting him promoted to the rank of major-general.

Byng would have none of Hughes’s pretensions. In early June 1916 Major-General Malcolm Smith Mercer*, commander of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, was killed in the battle of Mount Sorrel [see Roderick Ogle Bell-Irving*]. Hughes promptly ordered Byng to replace him with his own son, Garnet Burk Hughes. Byng just as promptly refused and appointed Brigadier-General Louis James Lipsett*, the experienced commander of the division’s 2nd Brigade, whom he promoted major-general. “To officer these splendid men with political protegées [sic] is to my mind little short of criminal,” Byng wrote to a friend. In late August the corps, whose men now referred to themselves as the “Byng boys,” left the Ypres salient for the Somme, in France, where British forces had been engaged since 1 July [see Francis Thomas Lind*]. In September the Canadians took more than 7,000 casualties in the battle of Courcelette [see Francis Clarence McGee*; James Cleland Richardson*], and they had suffered over 24,000 by the time the Somme offensive ended two months later.

In January 1917 Byng received orders to capture the whole crest of Vimy Ridge, which the Germans had held against repeated French assaults in 1915. He was given some time to prepare for the battle. Byng’s plan for the attack was ready in early March. It was laid out in meticulous detail. Behind the lines a replica of the battlefield was created for units in reserve to rehearse their assignments over and over until each unit of the corps knew its role and objective, and that of its neighbours on the left and right. And nightly, under the cover of the artillery bombardment of the German positions, Canadian soldiers practised advancing through barbed wire right up to the enemy lines. Each of the four Canadian divisions was aligned in numerical order from left to right, and they would begin their attack together at 5:30 a.m. Each unit was under a strict timeline to advance to a specified place and halt to regroup before proceeding. Simultaneously, the attack would be coordinated with artillery barrages designed to achieve several goals, including the destruction of the barbed-wire defences that protected German lines.

The preparatory artillery bombardment began on 20 March, lasted nearly three weeks, and battered German positions with more than a million rounds. In darkness on 9 April, the Canadians moved into their forward positions, ready for the pre-dawn attack. Gerald William Lingen Nicholson, the CEF’s official historian, notes that at 5:30, “with the thunderous roar of the 983 guns and mortars supporting the Canadians,” the attack on Vimy Ridge began. Byng envisaged that complete success could be achieved in less than two days. That did not happen. Not all the intermediate goals were reached on his schedule, and he may have underestimated the fierce resistance put up by the Germans. By the afternoon of 14 April the northern tip of Vimy Ridge, the last position to be taken, was finally in Canadian control. Altogether the corps had gained 4,500 yards and captured 54 German heavy guns, 124 machine guns, 104 trench mortars, and 4,000 prisoners. The price had been high: 10,602 casualties were suffered by the attackers, including 3,598 killed. The ridge, however, belonged to Byng’s Canadian Corps, and it would be kept until the end of the conflict. Relieved and elated, Julian wrote Evelyn, “Thank God nobody lost his head and the good old Canucks behaved like real disciplined soldiers.”

Vimy Ridge was Byng’s last major assignment with the Canadian Corps. He had twice turned down requests from Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the BEF, to lead one of its five armies, and he could not refuse when Haig ordered him in June 1917 to take over the 3rd Army, having named him temporary general. (His replacement as leader of the Canadian Corps was Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur William Currie, commander of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division.) In mid October Byng’s army was assigned the role of leading the British forces in an attack at Cambrai, in northern France. Unlike the contested area at Vimy, this battleground was on a flat plain, and the front line had been largely untested. Byng, taking lessons from Vimy, once again developed a meticulously detailed plan that included rehearsing his troops behind the front. There were new features: the advance would be covered by aircraft, and the ground forces would be supported by the heavy use of tanks. To retain the element of surprise, there was to be no artillery bombardment. Tanks would lead the charge to open channels through barbed-wire emplacements, allowing the infantry, backed by cavalry regiments, to quickly advance and engage the Germans. The assault, scheduled for 20 Nov. 1917, was to be aided indirectly by British and Canadian forces who were tying up the enemy at the ongoing third battle of Ypres, better known as Passchendaele.

Just eight days before the scheduled attack, however, Haig suddenly shut down the Passchendaele offensive, and reserve units essential to the Cambrai plan were sent to Italy. Still, Haig ordered the attack to proceed. Byng, whose Canadian units at Vimy had been able to rehearse their assignments for several weeks before the battle, had only two days to prepare his men at Cambrai because of the short time between Haig’s authorization and the date of the attack. Byng might have protested but did not. The assault began at dawn on 20 November and was initially a major success, with 3rd Army troops advancing three to four miles on a six-mile front. The march forward did not last. German forces, reinforced by new reserves, halted the British momentum, and by the end of the month they had recovered much of the ground taken by Byng’s troops. There was no brilliant follow-up at Cambrai to Byng’s shining victory at Vimy. Nonetheless, his innovative use of air and ground forces in a concerted attack was unprecedented for the British, and it would become the model for battle tactics in World War II. Before the fighting ended early in December, Byng had been raised to the full rank of general (23 November).

In January 1918 the BEF’s area of responsibility on the Western Front was extended, but its manpower was not significantly increased. Byng and the 14 divisions of the 3rd Army were given the task of defending 28 miles of the line in northern France. That spring the Germans launched a massive offensive that was intended to end the war. It was initially successful, but, exhausted, they halted on 17 July. On 8 August the 4th Army, led by Currie’s Canadians along with Australian troops, began a counter-attack at Amiens that broke the German line. In the Last Hundred Days campaign that demanded so many sacrifices [see Hugh Cairns*; Archibald Ernest Graham McKenzie*; Charles James Townshend Stewart*], the Germans were driven back towards their own territory. Byng’s men were fully engaged in this final push, during which the 3rd Army lost more than 115,000 who were killed, wounded, or missing by 11 Nov. 1918, the day of the armistice.

After the war Byng, now 56, returned to England, where he and Evelyn resided in Thorpe Hall, a manor house in Thorpe-le-Soken, Essex, that they had purchased while he was stationed in Egypt. He briefly worked at the War Office and was given the option of leading the Southern Command, but declined the post. In July 1919 he was offered the chairmanship of the United Services Fund (USF), which provided dedicated support to former soldiers and their families. Byng accepted on the condition that the fund would be independent of the government and the military, which meant that he had to resign from the army to take up his new post. Under his leadership the USF was, like all of Byng’s organizations, tightly run: it had a meagre staff of one secretary and two clerks who coordinated and depended upon a large group of volunteers across the country.

In August Byng was elevated to the peerage as Baron Byng of Vimy and Thorpe-le-Soken and received a grant of £30,000 from parliament in appreciation of his military services; Canada, in turn, made him honorary general of the Canadian militia the following year. In 1921 the Colonial Office suggested that Byng be appointed governor general of Canada, in succession to the Duke of Devonshire [Cavendish], whose five-year term was about to expire. To its surprise the idea was given a cool response by the Conservative government of Arthur Meighen*. Sir Robert Borden, whom Meighen had replaced in 1920, had been displeased with Devonshire’s predecessor, the Duke of Connaught [Arthur*], who had attempted to shape Canadian policies early in the war by exerting his influence as a field marshal. Borden had insisted that Connaught’s successor be a civilian, and both he and Meighen felt that Devonshire had been a model governor general.

To ease Meighen’s concern over interference from another military figure, Winston Churchill, secretary of state for the colonies, sent him a list of candidates to consider. Churchill recommended Baron Desborough or the Earl of Lytton. The Canadians approved of Desborough, but he refused the appointment and they did not want Lytton. Meighen then accepted the suggestion of Byng, who had long before committed himself to taking up the position if offered it. His appointment was announced on 3 June 1921. On 2 August Byng received his commission as governor general and commander-in-chief of the Dominion of Canada. He also received a gcmg from King George V, who told Byng not to worry about his lack of viceregal experience. “You will be just like a king in your kingdom,” His Majesty assured him, to which a grinning Byng replied: “Oh no, Sir. More likely I shall just be Byng in my Byngdom.”

Julian and Evelyn arrived in Quebec City on 10 August, a day ahead of schedule, and the next morning they were welcomed to Canada by Meighen and Quebec premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau*. Byng took the oath of office in the legislative building, where a luncheon was given in his honour by the federal government. Roger Graham, Meighen’s biographer, records that Byng told his prime minister: “I’ve never done anything like this, you know, and I expect I’ll make mistakes. I made some mistakes in France, but when I did the Canadians always pulled me out of the hole. That’s what I’m counting on here.” The next morning the party arrived in Ottawa and was greeted on Parliament Hill. William Lyon Mackenzie King*, the leader of the Liberal opposition, noted in his diary that “the day was very bright & clear, an enormous crowd were present,” and the governor general was received by a guard of honour composed of returned soldiers.

At Rideau Hall, the governor general’s official residence, Byng was united with the staff he had selected before sailing for Canada. Arthur French Sladen, his private secretary, and Captain Oswald Herbert Campbell Balfour, his military secretary, had served under Devonshire; Lieutenant-Colonel Humphrey Waugh Snow was controller. Breaking with precedent, Byng insisted on having a Canadian presence in his household: Major Henry Willis-O’Connor became his aide-de-camp, and Major Georges-Philéas Vanier* of the Royal 22nd Regiment was another aide. On the social side, Ottawa, with a population of just over 100,000, had a small and tight-knit social elite whose members tended to treat Rideau Hall as their own little bit of England. They soon regarded Lord and Lady Byng, who broadened the guest list at their residence, with some suspicion: Byng was only a baron, after all, and a new one at that, whereas his two most recent predecessors had been dukes. A welcome change, however, was that Julian and Evelyn held frequent lunches and dinners for small groups of parliamentarians from all parties, during which they learned much about Canada. They also took a liking to hockey, and in 1925 Evelyn would donate a cup to the National Hockey League, the Lady Byng Trophy, which has since been awarded annually to the league’s most gentlemanly player.

A major responsibility of the governor general was to see, and be seen, in places across the country. Julian and Evelyn, experienced travellers, took to this task eagerly. During his tenure they made four extended tours of western Canada using the viceregal train and, on the coasts and the Great Lakes, steamer services. They also spent time in the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, rural Quebec, and the Maritimes. Unpretentious and cheerful, Byng was very popular with Canadians. In rural Alberta, for example, he encountered a farmer who knew that the governor general was visiting and, not recognizing Byng, wondered what the “old bugger” was like. Byng replied, “Oh, not so bad on the whole,” and urged him to come and see for himself at a reception the next day. There, he asked the surprised and amused farmer, “Well, is the old bugger so bad after all?” Byng often showed his regard for ordinary Canadians. In July 1923 he and Evelyn visited Sydney, N.S., at a time when striking steelworkers and coalminers were essentially in control of the city. The federal government feared violence and advised Lord and Lady Byng not to go, but they went anyway, refused the recommended police protection, and were welcomed joyously by huge crowds of strikers. While in Nova Scotia, Byng even met with union leaders James Bryson McLachlan and Daniel Livingstone, and promised that if they guaranteed an end to the coalminers’ work stoppage, he would support the withdrawal of provincial police from the area (the agreement was short-lived, owing to the renunciation of McLachlan and Livingstone by the strikers’ international union).

Byng’s principal duty was, ultimately, to work with the government of the day. Though he had several meetings with Arthur Meighen after his arrival, Byng had little time to become acquainted with the prime minister before his party was defeated by King’s Liberals in the general election of 6 Dec. 1921. The new government was sworn in on the 29th, and three days later King, after receiving a cordial New Year’s greeting from the governor general, predicted in his diary, “I believe our relations are going to be very pleasant, happy and mutually beneficial.” In February 1922 Byng, having just attended a meeting of the Boy Scouts in Toronto, asked the prime minister if it would be proper for the governor general to take a prominent role in the movement in Canada. King replied that it would be and, on a later occasion, noted Byng’s conviction that the scout movement fostered patriotism.

Over the next four years, King and Byng had frequent talks about foreign affairs and the imperial connection. Although the governor general traditionally acted as both the sovereign in Canada and the British government’s representative, Byng set an important precedent by refusing to perform in the latter role. He maintained that it would be more appropriate for the British to have a diplomat in Ottawa and for Canada to have its own ministerial-level representative in London. The governor general’s attitude suited King, who stressed that, as a self-governing dominion, Canada did not need supervision from Great Britain. “It was interesting,” King wrote in April 1925, “to see how clearly Lord Byng saw the essentials of this.”

Near the end of Byng’s term of office, there was a change in his normally cordial and cooperative relationship with the prime minister. In the general election of 29 Oct. 1925 Meighen’s Conservatives won 116 seats, the Liberals took 99, and the agrarian-based Progressives [see Thomas Wakem Caldwell] won 24; the Tories were thereby narrowly denied a majority in the House of Commons. King had lost his own seat, and Byng and many others expected him to resign as leader of the party, but he did not. He instead told Byng that his caucus had insisted he meet the house, and that he believed he would prevail with the support of the Progressives. Byng accepted this course of action but warned the prime minister that he must not “at any time ask for a dissolution unless Mr Meighen is first given a chance to show whether or not he is able to govern.” King agreed to this condition. The house convened on 7 Jan. 1926, with King watching from the visitors’ gallery. He soon obtained a seat in a by-election, and he was able to carry on through the spring with Progressive backing.

During the session, however, news broke of a major scandal: some members of the Department of Customs and Excise, including Jacques Bureau, the former minister, had connived with smugglers to bring goods into Canada from the United States. In February the house passed a motion by Conservative mp Henry Herbert Stevens* to set up a special parliamentary committee to investigate the matter, and when it reported in June, Meighen and the Conservatives moved a vote of censure against the government. King, who was desperate to avoid the vote, suggested to Byng on 26 June that dissolving parliament was the only course. When the governor general reminded the prime minister of his promise not to ask for a dissolution before giving Meighen a chance to govern, King observed that in the last hundred years no British sovereign, or sovereign’s representative, had turned down such a request from a prime minister. Byng replied that no prime minister had ever sought a dissolution to avoid facing a vote of censure, and he urged King not to make a demand that he knew would be denied. Nevertheless, on 28 June King formally asked that parliament be dissolved. When Byng refused, King immediately resigned, leaving Canada without a national government.

That afternoon Byng asked Meighen if he could form a government, and after consulting with Borden, he returned to Rideau Hall just before midnight to say that he would do so. Meighen’s position was precarious. An mp who was promoted to cabinet had to resign and seek re-election, but if Meighen, and any ministers he appointed, did so, the government’s chances of winning a vote in the house would be jeopardized. Meighen resigned his seat but used the expedient of appointing six of his colleagues (William Anderson Black, Hugh Guthrie, Sir George Halsey Perley, Sir Henry Lumley Drayton*, Robert James Manion*, and Stevens) as acting ministers so that they could keep theirs. The Conservatives carried three votes, including the motion of censure against the former King administration, but on 2 July a Liberal motion calling into question the validity of the “acting” government was passed by a single vote. Meighen had been given his chance, taken it, and lost. Byng granted his request for a dissolution, and a general election was called for 14 Sept. 1926.

The tone of the ensuing contest was especially bitter. Meighen, who was contemptuous of King, hoped that the customs scandal and the standard planks of the Tory platform would carry him to victory, while King, who despised Meighen, characterized the governor general’s decision to refuse him a dissolution as interference with Canada’s autonomy. Byng, who could say nothing publicly during the campaign because of his position, was convinced that he had done the right thing. Constitutional expert Eugene Alfred Forsey* would vindicate Byng in his definitive 1943 study, The royal power of dissolution …, and in 2005 Herbert Blair Neatby, King’s primary biographer, acknowledged that “in constitutional terms, Byng was right and King was wrong.” In political terms, however, King had won the day. The Liberals took 116 seats and Liberal-Progressive candidates were elected in 10 ridings, giving King a working majority against 91 Conservatives and 10 Progressives. Meighen, who lost his own seat, resigned as prime minister and, shortly afterwards, as Conservative leader.

Lord and Lady Byng, who had been scheduled to leave Canada earlier in the summer, delayed their departure until the election was over. Their responsibilities were now fulfilled. On 27 Sept. 1926 King accompanied Byng to parliament and the Memorial Chamber of the Peace Tower, where the governor general laid the stone for the Altar of Remembrance. King then bid him goodbye at the railway station. In his diary he noted that Byng “got a good send-off,” but also that “it was a strange sort of farewell. I was mighty glad when it was over.” The Byngs departed Canada from Quebec City. King did not accompany them there, instead sending two junior ministers to represent the government.

Back home in England, Byng, who was made a viscount in October 1926, found himself without a job for the first time since joining the army so many years earlier. For the next two years he and Evelyn pursued their various interests and enjoyed living in Thorpe Hall. Byng briefly lent a hand at the High Commission of Canada in London, helping to develop a plan to encourage emigration to Canada. In June 1928 the home secretary asked him for advice on the appointment of a new chief commissioner of the city’s Metropolitan Police and then quickly decided that Byng himself was the best candidate for the job. Byng refused several times but finally gave in, and his appointment was announced on 2 July. That fall, after receiving an inheritance from Evelyn’s maternal uncle, the Byngs purchased a house in London at 4 Bryanston Square. From there, and from Thorpe-le-Soken, Byng carried out his duties as chief commissioner and entertained at home with Evelyn; the couple also made time for travelling abroad.

On 26 July 1930, while Georges Vanier was visiting Thorpe Hall, Byng had a heart attack. In October of the following year he resigned the commissionership. In April 1932, after a trip through the Panama Canal, he and Evelyn landed in Victoria and then took a long cross-country tour of Canada. In October he was promoted to the rank of field marshal, an honour that meant more to him than any other. Early in 1935, during a trip to California, Byng had a slight stroke, and in late May, after returning to England, he complained of abdominal pain. Doctors determined that he needed major surgery, but his heart was too weak to endure it. Viscount Byng of Vimy died early on the morning of 6 June 1935. His funeral was held two days later. The memorial services in Ottawa and Montreal were crowded, and prayers were said in churches across the country.

Julian Byng, born into an aristocratic but penny-poor family, began his military career as a junior officer in an ordinary militia regiment. But soon, thanks to his father’s friendship with the Prince of Wales, Byng was commissioned a lieutenant in a prestigious cavalry regiment in India. So began a succession of promotions, with service in the Sudan, South Africa, England, and Egypt prior to World War I, at which time he was called upon to lead the British 3rd Cavalry Division on the Western Front and then to successfully extract the 9th Corps from disaster at Gallipoli. His leadership skills, careful planning, detailed rehearsal, precise timing, and steady confidence in his subordinates were long acknowledged by many colleagues. All of these attributes were strikingly apparent at Vimy Ridge, where he directed the Canadian Corps to its greatest triumph. As leader of the British 3rd Army, Byng’s novel use of infantry, tanks, and aircraft in a unified battle strategy was only modestly successful at Cambrai, but he provided the standard for attacking forces in World War II. During his term as governor general, Byng and his beloved wife Evelyn were exceedingly popular with Canadians owing to their genuine graciousness and generous friendliness, traits that had been uncommon in earlier occupants of Rideau Hall. Byng’s life and career were that of a remarkable leader of men.

LAC, “Diaries of William Lyon Mackenzie King,” 12 Aug. 1921; 1 Jan., 3 Feb. 1922; 26 Jan. 1924; 1 April 1925; 15, 27 Sept. 1926: www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/politics-government/prime-ministers/william-lyon-mackenzie-king/Pages/diaries-william-lyon-mackenzie-king.aspx (consulted 10 May 2017). U.K., Parl. Arch. (London), BLU/1 (Papers of Ralph David Blumenfeld, corr.)/4/BY.14, BY.15, BY.18. D. J. Bercuson and J. L. Granatstein, Dictionary of Canadian military history (Toronto, 1992). R. C. Brown, “Cavendish, Victor Christian William, 9th Duke of Devonshire,” DCB, XVI. [M. E. Byng], Viscountess Byng of Vimy, Up the stream of time (Toronto, 1945). Tim Cook, At the sharp end: Canadians fighting the Great War, 1914–1916 (Toronto, 2007); Shock troops: Canadians fighting the Great War, 1917–1918 (Toronto, 2008). Cyril Falls, “Byng, Julian Hedworth George,” rev. Jeffery Williams, ODNB. E. A. Forsey, The royal power of dissolution of parliament in the British Commonwealth (Toronto, 1943). Nikolas Gardner, “Julian Byng: Third Army, 1917–1918,” in Haig’s generals, ed. I. F. W. Beckett and S. J. Corvi (Barnsley, Eng., 2006), 54–74. L. A. Glassford, “Meighen, Arthur,” DCB, XVIII. Roger Graham, Arthur Meighen: a biography (3v., Toronto, 1960–65), 2. J. L. Granatstein, “King, (William Lyon) Mackenzie (1874–1950),” ODNB. H. B. Neatby, “King, William Lyon Mackenzie,” DCB, XVII. G. W. L. Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914–1919: official history of the Canadian army in the First World War (Ottawa, 1962). Vimy Ridge: a Canadian reassessment, ed. Geoffrey Hayes et al. (Waterloo, Ont., 2007). P. B. Waite, “Meighen, Arthur (1874–1960),” ODNB. Jeffery Williams, Byng of Vimy: general and governor general (London, 1983).

Cite This Article

Robert Craig Brown, “BYNG, JULIAN HEDWORTH GEORGE, 1st Viscount BYNG,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/byng_julian_hedworth_george_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/byng_julian_hedworth_george_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert Craig Brown |

| Title of Article: | BYNG, JULIAN HEDWORTH GEORGE, 1st Viscount BYNG |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | April 29, 2025 |