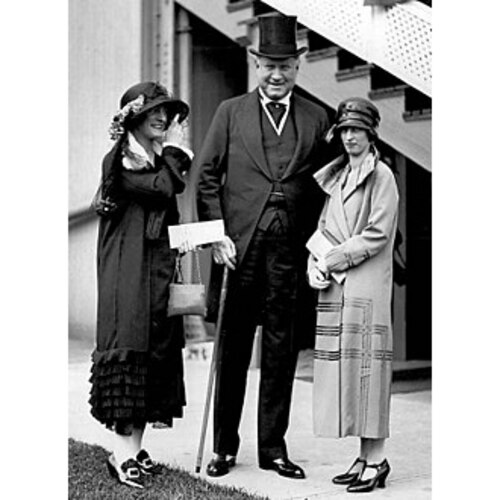

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

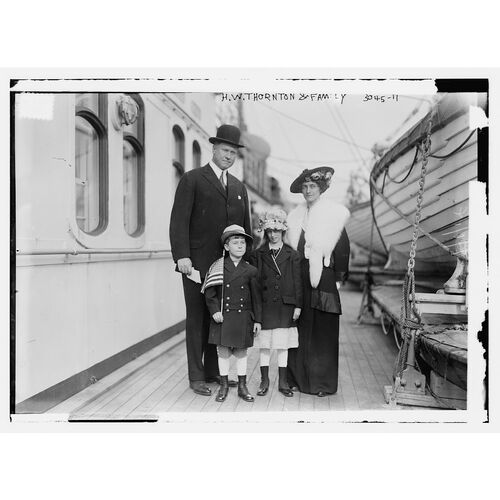

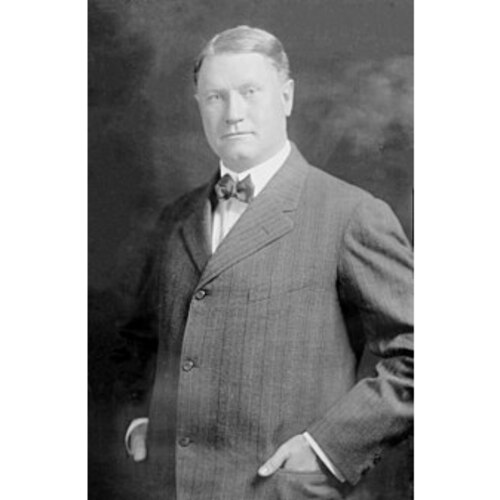

THORNTON, Sir HENRY WORTH, engineer and railway president; b. 6 Nov. 1871 in Logansport, Ind., fifth of the ten children of Henry Clay Thornton and Millamenta Comegys Worth; m. first 20 June 1901 Virginia Dike Blair (1881–1944), probably in New Castle, Lawrence County, Pa, and they had a daughter and a son; they divorced on 6 July 1926; m. secondly 11 Sept. 1926 Martha Watriss at Long Point on Chautauqua Lake, northwest of Jamestown, N.Y., and 13 Sept. 1926 in Philadelphia (two ceremonies were held to circumvent possible legal problems stemming from his divorce); they had no children; d. 14 March 1933 in New York City and was buried in Newtown, Bucks County, Pa.

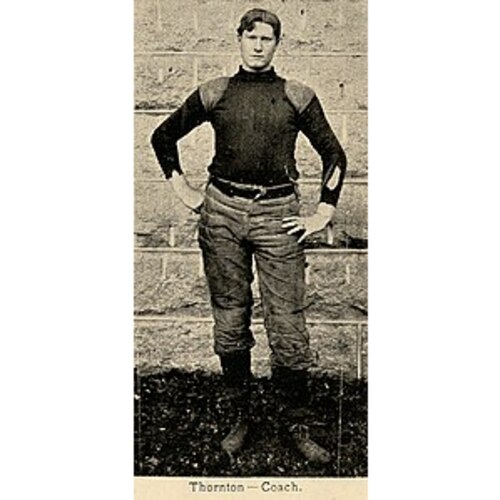

Henry Thornton grew up in Logansport, where his father was a prominent lawyer. He received his education at St Paul’s School in Concord, N.H., and the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, where he was a football linebacker – Thornton was six feet three inches tall and solidly built – and, during his freshman year, class president. He graduated with a degree in civil engineering in 1894. After serving briefly as the football coach at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., Thornton began to work, as the New York Times would later put it, “on the lowest rung of the ladder” in the Pittsburgh, Pa, office of the Pennsylvania Railroad. He was made a supervisory engineer in 1899 and division superintendent two years later. In 1911 the company appointed him general superintendent of its busiest commuter line, the Long Island Rail Road.

Thornton’s skilful direction of the LIRR drew the attention of the wider railway world, and in 1914 he became general manager of England’s Great Eastern Railway, with a mandate to modernize (and, some feared, to Americanize) a company that operated not only one of the country’s largest and busiest commuter systems, but also steamships, hotels, and other passenger and tourist facilities. Defying earlier British managerial practices, which imposed deference to class and status, Thornton adopted an open and egalitarian approach. He established personal contacts and gained warm support from workers in all ranks, thereby enhancing morale and productivity.

World War I broke out within months of Thornton’s arrival in London, and the British government nationalized the country’s railways for the duration of the conflict. Because he had experience in managing large commuter systems and their ancillary facilities, Thornton was given major responsibilities for the efficient movement of troops and military supplies. He thus added to his role as general manager of the Great Eastern the successive positions of deputy director of inland waterways and docks and assistant director general of movements and railways (1917), deputy director general of movements and railways (1918), and inspector general of transportation (1919). While fulfilling these duties, he rose to the temporary rank of major-general in the British army.

Citizens of the British empire, including Canadians, answered the call to fight in Europe, and Thornton’s responsibilities included coordinating their arrival in the British Isles from their own countries and their departure for France or Belgium. On the Western Front it was necessary to repair or reconstruct heavily damaged railways and other transportation facilities, and innovative strategies were required to cope with the devastated terrain. For example, light tracks, which often could be travelled only by cars pulled by horses, mules, or men, were laid for the transportation of supplies and the retrieval of injured or dead soldiers. A Canadian Overseas Railway Construction Corps was established in 1915 and, after being reorganized as the Corps of Canadian Railway Troops in the spring of 1918, would be placed under the command of Brigadier-General John William Stewart, who had been appointed deputy director general of transportation (construction) in January 1917. He worked closely with Thornton, who, as deputy director general of movements and railways, was in charge of moving men, materials, and supplies. His work earned him multiple honours: Great Britain made him a kbe, Belgium awarded him the cross of officer in the Order of Leopold, France inducted him into the Legion of Honour, and the United States gave him the Distinguished Service Medal.

After the war the Great Eastern Railway was amalgamated with other lines into the London and North Eastern Railway, and Thornton was dissatisfied when he was not appointed general manager of the new company. An opportunity then arose in Canada, whose railway system had recently undergone radical change. Wartime exigencies had left two new lines financially ruined: the transcontinental Canadian Northern Railway, established by William Mackenzie* and Donald Mann, and the rival Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, which ran from Winnipeg to Prince Rupert, B.C., and was an affiliate of the larger Grand Trunk Railway [see Edson Joseph Chamberlin*; Charles Melville Hays*]. After giving monetary assistance to the two struggling lines and calling a royal commission (co-chaired by Sir Henry Lumley Drayton*) that recommended both be nationalized, the federal government of Sir Robert Laird Borden took over the Canadian Northern in 1917. The line was merged the following year with two other publicly owned and operated railways: the National Transcontinental, which ran from Winnipeg to Moncton, and the Intercolonial, which served the Maritime provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. This conglomeration, described as the Canadian National Railways and headed by former Canadian Northern vice-president David Blythe Hanna, soon grew even larger, increasing its total trackage to roughly 22,000 miles through the absorption of the Grand Trunk Pacific in 1920 and the Grand Trunk itself two years later.

Hanna resigned in July 1922, partly because of political pressure from the Liberal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King*, and left to his successor the challenge of combining five railways, built to compete with one another and possessing sharply differing business strategies and cultures, into a unified system. The task, one critic lamented, would be as difficult as stitching five spider webs together. A strong president, one not rooted in the ethos of any of the component companies, was needed, and in June 1922 James Henry Thomas, a British mp and trade-union leader who had become general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen in 1917, recommended Thornton to King. The prime minister met Sir Henry in Ottawa on 4 October and was impressed by his “fine directness & breadth of view” as well as his “genial manner & quiet reserve.” Although Thornton’s experience was mainly with commuter lines and the CNR’s constituent lines were primarily freight carriers, King, who valued Sir Henry’s “quality of getting on with men & particularly with Labor,” invited him to become president and chairman of the board. He accepted the offer and an annual salary of $50,000, an amount equal to that earned by Governor General Lord Byng and Edward Wentworth Beatty*, president of the successful Canadian Pacific Railway, which was privately owned and operated. That night King wrote in his diary, “This has been a record day in the history of our party and country.”

Asked why he had accepted such a daunting position, Thornton would later say simply: “I like a good fight. Here was certainly the place to have it.” He had to address three major challenges. The first was the CNR’s relationship with its only shareholder, the Government of Canada. The history of the publicly built and operated Intercolonial was not encouraging. It ran along a circuitous and uneconomic route [see Walter M. Buck*; Sir Sandford Fleming*] and had incurred heavy losses that were due at least in part to patronage-plagued appointments, the construction of popular but unprofitable branch lines and facilities, and low freight and passenger rates that had been set to satisfy political interests. The royal commission had insisted in 1917 that the newly nationalized railway must follow sound business practices, and before taking the job Thornton had secured a promise from King that the government would not meddle in the company’s affairs. Sir Henry’s relations with the Liberals would be fraught with tensions, but he got along amiably enough with the prime minister and would enjoy the staunch support of Charles Avery Dunning*, minister of railways and canals between 1926 and 1929. The Liberals allowed Thornton to pursue independent policies, some of which were expensive and controversial; he would not fare nearly as well after the onset of the Great Depression and the subsequent election of a Conservative government.

The second problem for the CNR was that it had inherited a crushing debt from its five component lines. It was impossible for the company to earn operating profits large enough to pay the heavy interest charges, let alone reduce the principal. The federal government therefore had to provide the CNR with periodic loans, an outcome that was the subject of debate and controversy. The debt issue was related to a third predicament: the difficulty of competing with the privately owned and operated CPR. Its construction had been financed mainly with federal cash and land-grant subsidies and its lines had been relatively well maintained, whereas the Canadian Northern and the Grand Trunk Pacific had relied initially on federal and provincial bond guarantees and later on government-backed loans, and their lines were in poorer condition. Because the Board of Railway Commissioners, which oversaw passenger fares and freight rates for all railways, used the CPR’s lower capital and operating expenses as the standard, it was very hard for the CNR to operate profitably.

The company’s political and financial problems were compounded by Thornton’s visionary and aggressively expansionist strategies. He was determined to make the CNR one of the great railways of the world, and was willing to spend whatever was needed to achieve this objective. He first had to fit together the diverse components of the system, abandon some uneconomic lines, re-route others, upgrade portions of the main lines and many branch lines, replace hundreds of old locomotives and thousands of other pieces of obsolete rolling stock, and update or rebuild many stations and freight- and passenger-handling facilities. Consolidation, modernization, and the search for greater efficiencies led to about 9,000 jobs, roughly eight per cent of the company’s total number of positions, being eliminated. Thornton worked hard to minimize these cuts, and was thereby able to maintain amicable relations with the continuing employees. In this regard, he was helped by the insistent demands of outspoken critics in parliament for much more severe spending reductions.

Thornton was determined to make the CNR a multifaceted transportation and communications system. He strongly supported experimentation with new tractive technologies, most notably diesel-electric locomotives. Telegraph and telephone facilities were improved and linked to radio in an effort to attract luxury-class passengers, who were supplied with receivers and earphones. Equipment for transmitting programs was installed in passenger lounges, stations, and hotels, and in 1923, using the best available technology, the company created North America’s first radio network. The following year a hockey game was aired for the first time, and the company gained exceptionally favourable publicity when it arranged Canada’s first nationwide radio broadcast, the celebration of Canada’s diamond jubilee held in Ottawa on 1 July 1927.

Under Thornton’s leadership, the CNR attempted to offer facilities and services that were equal or superior to those of its rivals. Like other railway men of his day, he sought to attract high-end passengers by constructing great hotels in major cities and by developing great mountain parks. In Alberta’s Jasper Forest Park [see Samuel Maynard Rogers] he built a luxurious lodge and numerous other attractions that were clearly designed to compete with the CPR’s hotel and recreational facilities in Banff’s Rocky Mountains Park. To encourage other passengers and generate freight traffic, the CNR established a Department of Agriculture and Colonization, which vigorously promoted immigration and provided assistance for people settling on homesteads in western Canada. Speaking at a luncheon in New York City on 15 Nov. 1924, Thornton declared: “We demand only that the immigrant possess five qualifications: sound mind and body, a willingness to live under our traditions – for we want no communists – an ability to earn a living with the help we offer, and that he be a Caucasian. Canada cannot afford to create for herself a racial or negro problem.” The company also spent heavily on steamships, docks, and harbours. Huge sums were invested, and in the 1920s there were commensurate increases in income and profits that allowed the CNR not only to cover its fixed charges, but also to pay down some of the principal of its debt. Unlike Beatty, the CPR’s president, Thornton did not have to worry about dividends or appreciation in the value of his railway’s shares. The federal government was happy as long as the loans it was providing to meet the company’s fixed costs were reduced.

Then the Great Depression hit, and attacks on Thornton’s aggressive policies multiplied. On 28 July 1930 the electoral victory of the Conservatives, whose leader, Richard Bedford Bennett*, had once done legal work for the CPR, added to Thornton’s problems. Some cabinet and caucus members opposed public ownership of railways on ideological grounds, and they found it offensive that Thornton’s expansionist policies were funded, directly or indirectly, by the federal government. They sympathized with Edward Beatty’s frequent complaint that his successful private company was unfairly forced to compete with a rival that could incur huge losses that would be covered out of the public purse. Beatty had often advanced proposals to unite the two systems under his company’s administration, but Canadians, particularly in the west, were adamantly opposed to the restoration of a CPR monopoly. Instead, greater emphasis was now placed on the need for the two companies to cooperate and share facilities, notably so-called union stations. Thornton was willing to do so, but feared the government would tilt such arrangements in the CPR’s favour.

Conservative critics also took aim at Thornton’s large salary (which had risen to $75,000) and extravagant lifestyle. For example, Robert James Manion*, the minister of railways and canals, objected to the “liquors, flowers, and other questionable items” that appeared on Thornton’s expense accounts. Sir Henry’s controversial personal life appears to have encouraged attacks by his enemies; D’Arcy Marsh, his biographer, admits that he “had a liking for the bright lights” and sometimes succumbed to “the most alluring of temptations which are prepared by experts for the perennially tired business man.” In July 1926 his wife, Virginia, had divorced him “on grounds of indignities and continuous incompatibility,” according to the New York Times. The social stigma then attached to divorce injured his public image, which was probably not improved by his marriage two months later to Martha Watriss, a wealthy American 27 years his junior.

By July 1932 it was clear to Thornton that at least some members of the Bennett government no longer had confidence in him, and on 1 August he stepped down from the presidency of the CNR. He was given a separation allowance of $125,000 but stripped of his pension, which his critics thought too generous considering the economic conditions of the time. King, now the leader of the opposition, judged in his diary that “Thornton has himself to blame … of late his bad habits have got the better of him and destroyed his judgment. Had he possessed a Christian faith & lived by it he would have been one of the greatest of men. As it is he is now a colossus fallen.”

Broken in health and perhaps also in spirit, Thornton moved to New York, where, allegedly insolvent, he died of cancer on 14 March 1933. (At the time of his death, politicians in Ottawa were debating the relations of, and proposals for greater cooperation between, the CNR and the CPR). He was buried in Newtown, Pa, the birthplace of his mother. A big man with a big vision, Sir Henry Thornton had sought to transform five large failed railways, each of which had numerous subsidiaries and its own history and administrative culture, into one of North America’s biggest and best systems. Under his administration the CNR did not become the great railway he had wanted to build, but he guided it through exceptionally turbulent times, ensured its survival, and laid the groundwork for its subsequent growth and success. He was a towering individual who was cut down by high living, lavish spending, huge debts, bitter political and ideological battles, and above all, the Great Depression.

LAC, “Diaries of William Lyon Mackenzie King,” 4 Oct. 1922, 19 July 1932: www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/politics-government/prime-ministers/william-lyon-mackenzie-king/Pages/diaries-william-lyon-mackenzie-king.aspx (consulted 29 June 2017). New York Times, 16 Nov. 1924, 28 July 1926, 15 March 1933. Can., Royal commission to inquire into railways and transportation in Canada, Report (Ottawa, 1917). Canadian National Railways: synoptical history of organization, capital stock, funded debt and other general information as of December 31, 1960, comp. A. B. Hopper and T. Kearney (Montreal, 1962). D. B. Hanna, Trains of recollection drawn from fifty years of railway service in Scotland and Canada, ed. Arthur Hawkes (Toronto, 1924). W. K. Lamb, History of the Canadian Pacific Railway (New York and London, 1977). Donald MacKay, The people’s railway: a history of Canadian National (Vancouver and Toronto, 1992). D’Arcy Marsh, The tragedy of Henry Thornton (Toronto, 1935). D. H. Miller-Barstow, Beatty of the C.P.R.: a biography (Toronto, 1951). T. D. Regehr, The Canadian Northern Railway, pioneer road of the northern prairies, 1895–1918 (Toronto, 1976). G. R. Stevens, History of the Canadian National Railways (New York and London, 1973).

Cite This Article

T. D. Regehr, “THORNTON, Sir HENRY WORTH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 27, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/thornton_henry_worth_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/thornton_henry_worth_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | T. D. Regehr |

| Title of Article: | THORNTON, Sir HENRY WORTH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | March 27, 2025 |