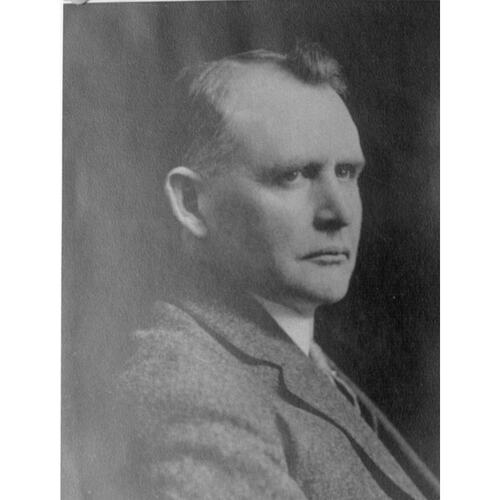

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

STEWART, JAMES DAVID, educator, lawyer, and politician; b. 15 Jan. 1874 in Lower Montague, P.E.I., son of David Stewart and Lydia Ayers; m. probably 20 July 1901 Barbara Alice Westaway (1879–1968) of Georgetown Royalty, P.E.I., and they had five daughters and two sons; d. 10 Oct. 1933 in Charlottetown and was buried there in the People’s Cemetery.

J. D. Stewart was born during a period in Prince Edward Island that helped define his career. The post-confederation era was characterized by struggles – to reverse economic stagnation, to check a rising tide of outmigration, to wrest concessions from the federal government, and to counter the drift towards political inconsequence – that would crest in the 1920s. Stewart’s beginnings were modest. The middle son in a Scottish farm family in Lower Montague, Stewart attended the local district school before proceeding to Prince of Wales College, headed by Alexander

In August 1901 Stewart articled to Georgetown lawyer and future premier John Alexander Mathieson*. Around the same time, he married Barbara Alice Westaway, who would later be described by her daughter Roma Alberta as a staunch Conservative partisan who possessed “uncommon shrewdness in judging people (Conservatives included).” Roma would become the first woman to practise law in Prince Edward Island, and her brother John David McLean Stewart* earned acclaim as a war hero and provincial politician.

On 27 Nov. 1906 Stewart was admitted to the bar. He then entered practice in partnership with Mathieson and Aeneas Adolph Macdonald, the firm being called Mathieson, Macdonald and Stewart. Politics increasingly drew the senior partners to Charlottetown, and Stewart evidently conducted the firm’s business in the Georgetown area. In 1916 Macdonald was appointed judge of the Probate Court, and a year later Mathieson, now premier, left office after being named the province’s chief justice on the retirement of Sir William Wilfred Sullivan*. By then Stewart had moved to Charlottetown, where on 11 May 1917 he was appointed kc. He would practise independently until 1928, when he took on his former clerk, barrister Norman Wright Lowther, as his partner.

In Prince Edward Island, law was often a path to politics, and in 1917 Stewart followed this path. According to Roma he was brought into the Conservative Party by his mentor, Mathieson, but “always remained at heart not quite committed.” Nevertheless, on 25 July Stewart won the 5th Kings seat left vacant when Mathieson was elevated to the bench. He would remain the dual riding’s legislative councillor until his death, holding the seat through four general elections.

Stewart had entered public life during perhaps the most tumultuous period in the province’s political history. Not only did the government change with every general election between 1919 and 1935, but the reversals of fortune were dramatic and precipitous. The first came on 24 July 1919 when Premier Aubin-Edmond

Over the next two years, Stewart proved an effective opposition leader. Although he did not dominate the rough and tumble of debate in the house, his set-piece speeches commanded respect. These addresses leaned more on reasoned argument and a detailed grasp of statistics than on rhetoric, and they were leavened with his trademark sarcasm. However able Stewart’s performance, his Conservatives did not so much win the next election as the Liberals lost it. Internal bickering weakened Bell’s cabinet as a persistent post-war recession wore thin Island voters’ patience. The premier had intended automobile revenues to finance the province’s investment in much-needed road construction under the provisions of the Canada Highways Act of 1919 [see Archibald William Campbell*], by which the federal government offered to pay 40 per cent of the cost. Bell was wrong in his calculations, however, and his government had to resort to tax increases, chief among them a highly unpopular $3.00 poll tax.

Caught between Islanders’ growing desire for government services and their traditional dislike of taxes, the Liberals were smashed. Bell ran on his highway policy; Stewart ran against Bell’s taxes. Practically reversing the results of 1919, the Conservatives took 25 of 30 seats in the general election of 24 July 1923.

When J. D. Stewart took office on 5 September, the premiership was in transition from part-time preoccupation to full-time job. Politics would consume the final decade of his life, to the detriment of his legal practice and his health. Fulfilling campaign promises, Stewart rescinded the poll tax and – in an act that damaged his own finances – lowered members’ sessional indemnities, which had more than doubled on Bell’s watch. The first major controversy of Stewart’s tenure involved one of the great controversial issues of Island life, religion. The proposed union in Canada of the Methodist, Presbyterian, and Congregational churches [see Samuel Dwight Chown; Clarence Dunlop Mackinnon] required enabling legislation in the Island legislature. Presbyterians who rejected union lobbied Stewart, a practising Presbyterian and member of Charlottetown’s Kirk of St James, for his support. Although he was personally opposed to church union and contributed financially to the dissident Presbyterian Church Association, he pledged only to ensure the regularity of the bill. After furious debate, it passed third reading on 11 April 1924, only to have the lieutenant governor, Murdock MacKinnon, withhold assent. The following spring MacKinnon’s successor signed a new version of the bill into law.

Stewart had campaigned on fiscal responsibility, promising tax reductions and more efficient administration. As it had to Stewart’s many predecessors, the goal of maintaining an adequate income without recourse to more taxes proved elusive. With a shrewd eye to its constituents, the government tinkered with rates of taxes on personal income and property and imposed a gasoline tax, the burdens of which fell heaviest on the wealthy few. Property taxes, which affected the farming many, were reduced, and Stewart promised to use highway taxes only for permanent road improvements. At the same time, his administration cast about for ways to reduce expenses. Besides cutting members’ indemnities, Stewart launched a campaign to force delinquent next of kin to pay towards the cost of their relatives’ care at Falconwood Hospital for the mentally ill, from which patients were being released on his orders to ease overcrowding. To avoid the cost of a royal commission on education, the premier convened a special committee of the cabinet to investigate the provincial school system. Such penny-pinching allowed his government to post a tiny surplus on its current account in his first year of office. Even so, Stewart could only slow the province’s fiscal slide. By his own admission during the assembly’s 1927 session, the government’s debt had increased by $315,511.15 between 31 Dec. 1923 and 31 Dec. 1926, with the total debt reaching $2,030,424.93.

Stewart’s preoccupation with retrenchment – and, of course, re-election – entailed making hard choices. Roads, deemed essential to economic progress, were a worthwhile reason for going into debt: in the 1923–26 period, the government paid for building highways by borrowing $340,000, a sum greater than the increase in its debt. Public health was given a much lower priority even though the Island had one of the country’s highest rates of mortality from tuberculosis [see Charles Dalton]; Stewart did begin modestly funding the provincial Red Cross Society in 1924. His effort to increase the Island’s population by recruiting immigrants from the Scottish Hebrides was hobbled by his concern for the province’s finances. He lobbied Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King* and the Canadian National Railways (CNR), led by Sir Henry Worth Thornton, for assistance, but the scheme fell through because Stewart was reluctant to contribute his own province’s money to the cause.

The most popular strategy for finding new revenues, of course, was to find them outside the province. In the 1880s, W. W. Sullivan had pioneered the tactic of making claims against the federal government for increased subsidies or financial compensation over a series of issues, chief among them Ottawa’s failure to fulfill the clause of the 1873 Confederation agreement that required the federal government to maintain continuous communications between the Island and the mainland. From this long-standing litany of complaint mixed with supplication, it was a short step to the province’s involvement in the Maritime rights movement of the 1920s. Contextualized by a spreading consciousness of the region’s declining economic and political position within the dominion, and catalyzed by a catastrophic rise in freight rates on the federally owned CNR, the Maritime rights movement loosely allied local and regional boards of trade, journalists, and regional politicians in a campaign to convince Ottawa that redress was needed to protect the Maritimes’ purported rights within confederation.

Stewart was quick to align himself with his fellow premiers in presenting a united front to the federal government. By 1926 he was the senior incumbent among them (the other premiers were New Brunswick’s John Babington Macaulay

Ernest Robert Forbes, the historian of the Maritime rights movement, has observed that it did not have the intensity in Prince Edward Island that it possessed elsewhere in the region. This is true. The industrial decline that lent urgency and anger to other Maritime-rights advocates was lacking in Prince Edward Island, but the province had its own pet grievances: high freight rates, delays in converting its railways from narrow to standard gauge, the need for a new railcar ferry to link the Island to the mainland, and the long-standing demand for greater federal subsidies. On freight rates and subsidies, Stewart found common ground with his fellow premiers, and he shared their satisfaction in 1926 when the royal commission on maritime claims, chaired by Sir Andrew Rae Duncan, recommended action on these fronts. Stewart would take particular credit for the King government’s subsequent interim increase in subsidies of $125,000 per year to his province, as well as an agreement that Ottawa would pay an additional $40,000 in subsidies in lieu of provincial taxes on the CNR’s Island operations.

With the return of prosperity to the province’s key industries, agriculture and fishing, and the news that the King government had accepted the Duncan commission’s recommendations, Stewart probably approached the general election of 1927 with confidence. At that point he made the most serious political blunder of his career. In 1900 the Island had been the first province in Canada to successfully enact a Prohibition law. Other provinces and, as a temporary war measure, Ottawa, had followed suit. But Prohibition proved both expensive and difficult to enforce, especially when many members of the community condoned at least some level of drinking. Strapped for revenue, Canadian provinces had one by one abandoned their ban on liquor in favour of government-controlled liquor sales. By the mid 1920s rumrunning and bootlegging were on the rise on Prince Edward Island. As early as January 1926, Stewart had vainly pressed his fellow Maritime premiers for uniform legislation on intoxicating liquors. In March 1927 he formally announced his government’s new policy at a pre-election testimonial dinner held in his honour. Prohibition, he declared, had failed to prohibit because too many Islanders did not support it: “A large proportion of our people, respecting law abiding citizens, … believe that they should not be deprived of the right to use intoxicating liquors … so long as their conduct towards society is what it should be.” He promised to enforce moderation, rather than Prohibition, by instituting government control of liquor sales to holders of legal permits.

It was a fatal miscalculation of the public mood. The rise in illegal drinking had pushed temperance advocates into militancy, not resignation. The Island’s Temperance Alliance mounted a massive campaign against Stewart’s new policy and, by extension, against the Conservatives. The opposition Liberals under Albert Charles Saunders* had only to promise more rigorous enforcement of the Prohibition Act of 1900, as well as a plebiscite on the subject, and then stand back to collect the political dividends. On 25 June 1927 they took 24 seats to 6 for the Conservatives.

Stewart stayed on as Conservative leader and in 1931 the wheel of fortune spun round once again. By then the Great Depression had prostrated the Island’s economy and crippled the Liberal government of Walter Maxfield Lea, who had succeeded Saunders. With a victory of 18 seats to 12 in the general election of 6 Aug. 1931, Stewart became the first post-confederation Island premier to return to power after being defeated.

His second term of office would be brief and despairing. Faced with massive unemployment, lengthening relief rolls, shrinking markets, and plunging commodity prices, the government repeatedly had to raise the overdraft ceiling to find enough money to get from one fiscal quarter to the next. To the federal minister of labour, Gideon Decker Robertson, Stewart wrote in October 1931, “Altogether the situation which we are now facing here is incomparably worse than anything that has ever been seen in this province in its recent history.” Within months the situation worsened when, seven weeks apart, Prince of Wales College and Falconwood Hospital were destroyed by fire, saddling the government with the heavy but unavoidable burden of rebuilding in the midst of the Great Depression.

Stewart drove himself hard. Already premier and attorney general, he functioned as acting minister of public works in 1932, and that November he shuffled his cabinet, personally taking on the duties of provincial secretary and provincial treasurer. By then he was seriously ill, evidently with heart and kidney troubles. He was intermittently able to preside over the executive council, but when the legislature met the following spring, he was rarely present and the government’s business was directed by his chief lieutenant and eventual successor as premier, William Joseph Parnell

When Stewart died on 10 Oct. 1933, both parties eulogized him for his honesty, integrity, and high principles, as well as his political skills. As premier, Stewart might loosely be described as a progressive. He craved efficiency, and, within the constraints of his government’s resources, he was a mild reformer. After returning to office in 1931, he had staffed the newly created Department of Education and Public Health and made Prince Edward Island the first province in the region to introduce old-age pensions, taking advantage of Prime Minister Richard Bedford Bennett*’s promise that the federal government would cover 75 per cent of the program’s cost.

For a public figure, J. D. Stewart had seemed unusually uncomfortable in the spotlight, a man of “retiring disposition,” as the Guardian noted in his obituary, whose greatest solace came from raising flowers. Although a skilled debater, he was no partisan. In the opinion of his daughter Roma, “political theory would have suited him better than practice.” She remembered him as being “not assertive enough, perhaps not physically strong enough, to be a rebel.” Instead, Stewart had been a sort of reluctant warrior. As was his province, his career had been constrained by what was possible as well as by what was necessary.

No collection of James David Stewart’s personal papers seems extant, and no will was probated for either Stewart or his widow. Some of Stewart’s official correspondence can be found in PARO, RG 25 (Premier’s Office fonds), s26, ss1 (James D. Stewart papers, subject files) and in s29 (James D. Stewart papers). There are virtually no surviving records from his second term. A copy of chapter 3 of R. [A.] Stewart Blackburn, “Hearth and home: a memoir” (n.p., [1981–84?]; typescript) is located in PARO, Acc4438.

LAC, R233-177-0, P.E.I., dist. Kings (139), subdist. Georgetown, Burnt Point, Georgetown Royalty (35): 18; R233-35-2, P.E.I., dist. Kings (3), subdist. Lot 59 (R): 63; R233-36-4, P.E.I., dist. Kings (133), subdist. Lot 59 (R), div. 1: 22–23; R233-37-6, P.E.I., dist. Kings (132), subdist. Township 59 (R), div. 1: 8; R233-177-0, P.E.I., dist. Kings (139), subdist. Georgetown, Burnt Point, Georgetown Royalty (35): 18. PARO, Acc4112 (Law Society of Prince Edward Island fonds), s2 (Presidents and members lists); Master name index, cemetery transcripts; RG 5 (Executive Council fonds), s1, ss1 (Minutes and orders-in-council, Minute books), 1917–33; RG 6.1 (Supreme Court fonds), s19 (Legal profession’s records), ss2, file 140 (Bar admittances, James David Stewart, 1906); RG 21 (Federal–provincial affairs fonds), s2, ss1. Charlottetown Guardian, 20 June 1892; 20 March 1900; 26 July 1917; 10 June 1921; 17 April 1923; 11 March, 2, 12 April 1924; 16, 19, 31 March 1927; 8 Aug. 1931; 11 Oct. 1933. Examiner (Charlottetown), 11 June 1921. Patriot, 10 June 1921; 28, 30 July 1923; 8 Aug. 1931; 11 Oct. 1933. D. O. Baldwin, “Volunteers in action: the establishment of government health care on Prince Edward Island, 1900–1931,” Acadiensis, 19 (1990), no.2: 121–47. Calendar of Dalhousie College and University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1898–99 (Halifax, 1898). Calendar of Prince of Wales College and Normal School, Prince Edward Island, Canada, 1899–1900 (Charlottetown, 1899). J. D. Cameron, “The garden distressed: church union and dissent on Prince Edward Island, part one,” Island Magazine (Charlottetown), no.30 (fall/winter 1991): 15–19; “The garden distressed: church union and dissent on Prince Edward Island, part two,” Island Magazine, no.31 (spring/summer 1992): 16–22. Leonard Cusack, A party for progress: the P.E.I. Progressive Conservative Party, 1770–2000 (Charlottetown, 2013). C. M. Davis, “I’ll drink to that: the rise and fall of Prohibition in the Maritime provinces, 1900–1930” (phd thesis, McMaster Univ., Hamilton, Ont., 1990). E. R. Forbes, The Maritime rights movement, 1919–1927: a study in Canadian regionalism (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1979). Earle Kennedy, “Tabling the legislature: one hundred years of general elections, 1893–1993,” Island Magazine, no.42 (fall/winter 1997): 13–24. [G.] E. MacDonald, “Bridge over troubled waters: the fixed link debate on Prince Edward Island, 1885–1997,” in Bridging islands: the impact of fixed links, ed. Godfrey Baldacchino (Charlottetown, 2007), 29–46; If you’re stronghearted: Prince Edward Island in the twentieth century (Charlottetown, 2000). W. E. MacKinnon, The life of the party: a history of the Liberal Party in Prince Edward Island ([Charlottetown], 1973). Greg Marquis, “Prohibition’s last outpost,” Island Magazine, no.57 (spring/summer 2005): 2–9. Minding the house (Weeks). Sharon Myers, “The apocrypha of Minnie McGee: the murderous mother and the multivocal state in 20th-century Prince Edward Island,” Acadiensis, 38 (2009), no.2: 5–28. P.E.I., Legislative Assembly, Journal, 1896–98, 1917–33.

Cite This Article

G. Edward MacDonald, “STEWART, JAMES DAVID,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 15, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stewart_james_david_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stewart_james_david_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | G. Edward MacDonald |

| Title of Article: | STEWART, JAMES DAVID |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2024 |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | December 15, 2024 |