Source: Link

ANDERSON, ALEXANDER, educator and office holder; b. 30 Sept. 1836 in Aberdeen, Scotland, son of Alexander Anderson and Margaret Imray; m. 11 Nov. 1862 Catherine Stewart Robertson in Alloa, Scotland, and they had three sons and a daughter; d. 13 Jan. 1925 in Halifax.

Alexander Anderson attended school in Aberdeen until 1854, when he led all of Scotland in the examinations for his year and won a scholarship to Moray House Training College for teachers in Edinburgh. He studied at this college for two years, was appointed a master in its training department, and later entered the University of Edinburgh. At the end of four years there, he won gold medals in mathematics and natural philosophy and a medal in chemistry.

In November 1862 Anderson and his bride sailed for Prince Edward Island, where he began teaching mathematics and science in Charlottetown at Prince of Wales College. A secular institution established by the government of Edward Palmer* in 1860, it was located in a dilapidated building formerly occupied by a boys’ school, the Central Academy. The college, though basically a high school, also offered what was apparently the equivalent of first-year university. In 1868 Anderson was appointed principal when the founding principal, Alexander Inglis, resigned and returned to Scotland. His gifts soon became evident. As early as the 1870s, when enrolment stood at about 70, graduates were being accepted for second-year work at such colleges and universities as McGill, Dalhousie, Harvard, and Cornell, and many won scholarships and prizes.

Their accolades bear witness to Anderson’s impact. One of his students in the 1870s was Jacob Gould Schurman of Freetown, who later attended universities in Edinburgh, London, and continental Europe, and would serve as a president of Cornell. “I have never yet met such a great teacher as Professor Anderson,” he once said. “There is none to whom, all considered, I personally owe so much as to him.” Sir Andrew Macphail*, a son of former school visitor William McPhail*, went to Prince of Wales in the 1880s before studying medicine at McGill. “Of the many teachers I have since known,” he would recall, Anderson was “the best.” In 1888 McGill awarded him an lld, citing the “excellent training” he provided and his role in improving the Island’s educational system.

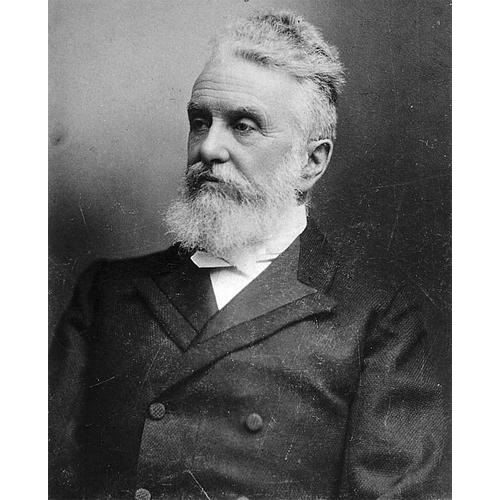

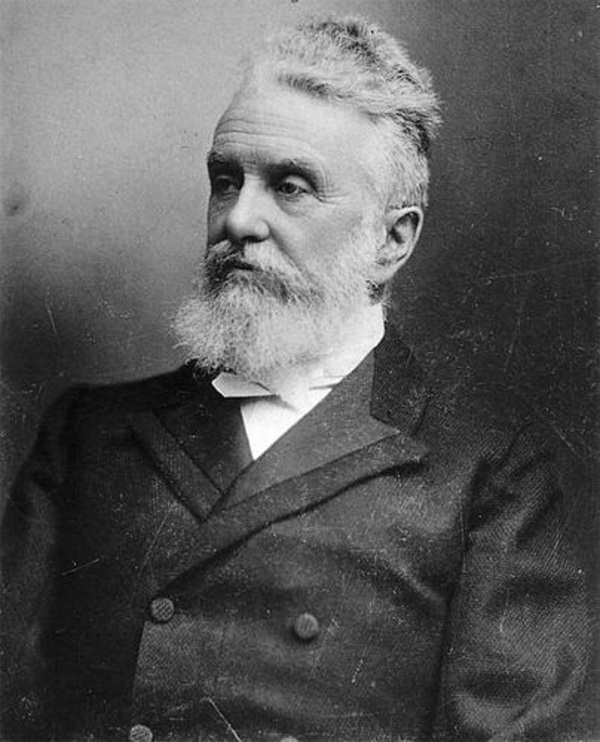

What makes Anderson’s success truly remarkable is the dismal state of elementary education in 19th-century Prince Edward Island. Year after year, inspectors’ reports complained of vacant schools, poorly qualified and ill-paid teachers, no standard curriculum, and irregular attendance. In the two decades after Prince of Wales opened, students could enrol there or in the adjacent Normal School virtually by knocking on the doors. Consequently, Anderson had to devote much of his time to remedial work, spending five to seven hours a day in the classroom. He loved to teach. Of all her teachers, recalled Lucy Maud Montgomery*, a teacher-training student in 1893–94, “none was to be compared to Dr. Anderson. I can see him now, standing before us, making the dry bones of Roman History live, and clothing even Greek verbs with charm and ‘pep.’” She knew him to be a hard marker who spared his praise, but he encouraged her to develop her writing talent. A stocky man with a beard and thick grizzled hair that stood up, the impeccably dressed Anderson presented a picture of dignity bordering on pomposity. He carried himself so ramrod straight that he almost leaned over backwards. Rarely known to rebuke a student, he established his authority effortlessly; he could quiet an unruly class simply by appearing in the room. He treated farm boys with esteem, as if they were destined for greatness. Some were. “Members of the government, of the judiciary, and of the professions had all passed through his school,” Macphail wrote, “and they retained for him a respect and fear not unmixed with affection. In addition the best schools were taught by his pupils, and they helped to propagate the legend of his power.”

Anderson’s beneficial influence did not mean that his college was safe from criticism, underfunding, or even the threat of abolition. It was totally dependent on the government and was vulnerable to interminable disputes over religion, politics, and education [see Sir Louis Henry Davies]. Almost half of the Island’s residents were Roman Catholics, and some of the fiercest fights centred on whether the government should give grants to public schools and Prince of Wales but not to Catholic schools and St Dunstan’s College. Anderson, a Presbyterian, apparently did not become involved in these conflicts. Instead, he concentrated on promoting education, giving lectures across the Maritimes on topics such as Burns, Shakespeare, and Savonarola, and serving as a director of the Dominion Educational Association and a member of its dominion history committee.

In 1879 the government decided to save money by amalgamating Prince of Wales and the Normal School, which had failed to live up to its promise as a teacher-training institution. With union, women were admitted to the college for the first time and all pedagogical training was placed under Anderson’s wing. With characteristic zeal, he immediately began reforming the Normal School. The next year Prince of Wales started screening students through entrance examinations. The failure rate was high; in 1893, for instance, fewer than half the 264 candidates passed. At the same time the entrance requirements encouraged the district schools to raise their standards, with Anderson constantly watching. In some of his annual reports, he spent as much time on the schools as on his college, praising and scolding the teachers and making suggestions for improving instruction. In 1896, for example, he noted that geography and history lessons seemed to be exercises in memorization. To foster a spirit of inquiry and “the faculty of attention,” teachers should make history come alive by reading adventure and travel stories to their classes and asking students to summarize them. More work on diction would improve spelling, he believed, and greater care should be paid to handwriting.

Toward the end of the century, Anderson added new courses to the curriculum, and enrolment continued to climb, reaching 246 by 1896. As well, he had attracted other forward-looking educators to his staff, among them Joseph-Octave Arsenault*, a professor of French, principal of the model school at Prince of Wales, and provincial inspector of French instruction in the Island’s Acadian schools. The college building, however, remained in bad shape: it had dark, narrow halls, overcrowded, poorly ventilated classrooms, and no assembly hall or library. Anderson complained that the lack of space made it difficult to keep order and impossible to conduct the teacher-training program properly. When unprecedented outbreaks of headaches, colds, influenza, measles, and other ailments occurred in the 1890s, he blamed the cramped space and fetid air. Every year for almost two decades he begged the government for a new building, but nothing was done.

The province was chronically short of money. By the 1890s the shipbuilding boom was over and farm incomes were in decline. In the end, it was left to Anderson to come up with a solution: collecting tuition fees, to be set aside to pay the interest on erecting a new school. Previously, teacher-training students had been exempt from fees even though not all of them went on to teach. By 1896 the college had taken in $3,300, and construction began two years later. In February 1900 a three-storey brick structure, with six classrooms, an auditorium, and space for a library, opened to great fanfare. A reporter from the Daily Patriot pronounced it “a tribute to the untiring energy of Dr. Anderson, and, best of all, a source of pride to the intelligent inhabitants of this little Isle of the Sea.”

Anderson had other ambitions for the college. For instance, he had been promoting degree-granting status for several years. He had seen many young Islanders leave the province for higher educations, including at least two of his children – his daughter studied in Paris and Hanover and a son went to the Royal Military College of Canada in Ontario. Unfortunately, he did not stay at Prince of Wales to press the issue. In March 1901, apparently satisfied that it was in good shape, he left to become the Island’s chief superintendent of education. Then 64, he attacked his new tasks with vigour, travelling to dozens of one- and two-room schools, giving teachers advice, consulting with trustees, and writing forceful, often indignant reports to the government. In many districts, the school facilities shocked him, as did the low salaries. One district had never adequately compensated a good, long-serving teacher. “Such treatment is not only selfish and unjust, but ungrateful and cruel,” he declared. Clearly ahead of his time, he promoted the consolidation of rural schools and argued that female teachers should be paid the same as male teachers. “Why . . . should such discrimination exist?” he asked in 1909. “Surely the time has arrived when men and women, who do the same work, under the same exacting circumstances, shall be put on an equality by the school law.”

It is difficult to measure Anderson’s effect on the school system, aside from his reform of teacher training, but his superintendent’s reports provide clues. In 1908 he expressed pleasure over the number of candidates who had performed well in the previous summer’s entrance exams. School facilities had improved considerably, he claimed in 1910; the next year he observed that local ratepayers had increased their contributions to teachers’ salaries every year since 1901. Teachers were showing readiness to adopt his suggestions, and he saw advances in penmanship, arithmetic, history, and geography. On the other hand, salaries were still so low by the time he retired that many good teachers had left the profession or the province. In addition, the experiment in 1905–11 in consolidating six school districts died when the financing from Sir William Christopher Macdonald* stopped.

Anderson retired in 1912 at age 76. In his eighties he moved to Halifax with his wife to live with their daughter, Helen Kingdon. He died in 1925 after a bout with pneumonia. Anderson did not live to see school consolidation, substantial improvements in teachers’ salaries, or university status for Prince of Wales, but during his lifetime, and for decades afterwards, the college served as a lighthouse for education. In 50 years of service, he fostered the development of countless teachers, professors, and administrators, turned Prince of Wales into an institution recognized by some of the best universities on the continent, and earned the gratitude of many accomplished sons and daughters. “If there be today in Prince Edward Island a good school system, good machinery, good teaching, good scholars,” J. G. Schurman declared, “it is all due, directly or indirectly to his genius for education.”

The author’s history of Prince of Wales College is forthcoming.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Geneal. Soc., International geneal. index. LAC, MG 30, D150. Examiner (Charlottetown), 8 Nov. 1875. Islander (Charlottetown), 5 Dec. 1862. Patriot (Charlottetown), 15 May 1873, 8 July 1893, 5 Feb. 1900, 13 Jan. 1925. Duncan Campbell, History of Prince Edward Island (Charlottetown, 1875; repr. Belleville, Ont., 1972). G. E. MacDonald, The history of St. Dunstan’s University, 1855–1956 (Charlottetown, 1989). Frank MacKinnon, Church politics and education in Canada: the P.E.I. experience (Calgary, 1995). Andrew Macphail, The master’s wife, intro. I. R. Robertson (facsimile ed., Charlottetown, 1994). M. O. McKenna, “The history of higher education in the province of Prince Edward Island,” CCHA, Study Sessions, 38 (1971): 19–49. L. M. Montgomery Macdonald, “The day before yesterday,” College Times (Charlottetown), 3 (1927), no.3: 29–34; The selected journals of L. M. Montgomery, ed. Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston (4v., Toronto, 1985–98), 1. P.E.I., House of Assembly, Journal (Charlottetown), reports of the principal of Prince of Wales College, 1881, app.A: 33; 1882, app.A: 57–58; 1892, app.E: 70; reports of the superintendent of education, 1872, 1879; Legislative Assembly, Journal (Charlottetown), reports of the principal of Prince of Wales College, 1897, app.E: 66; 1898, app.E: 65; reports of the chief superintendent of education, 1901–12. Past and present of Prince Edward Island . . . , ed. D. A. MacKinnon and A. B. Warburton (Charlottetown, [1906]). I. R. Robertson, “Religion, politics, and education in Prince Edward Island from 1856 to 1877” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1968).

Cite This Article

Marian Bruce, “ANDERSON, ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/anderson_alexander_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/anderson_alexander_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Marian Bruce |

| Title of Article: | ANDERSON, ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |