Source: Link

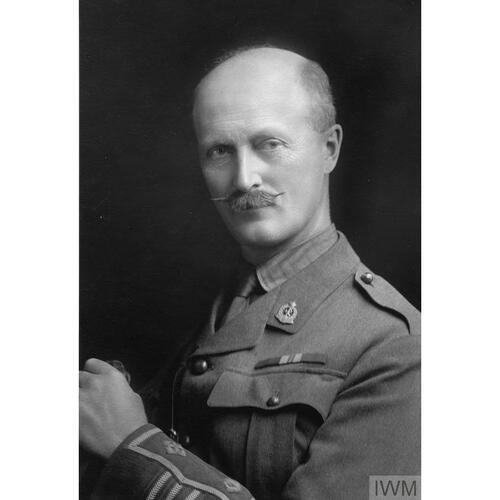

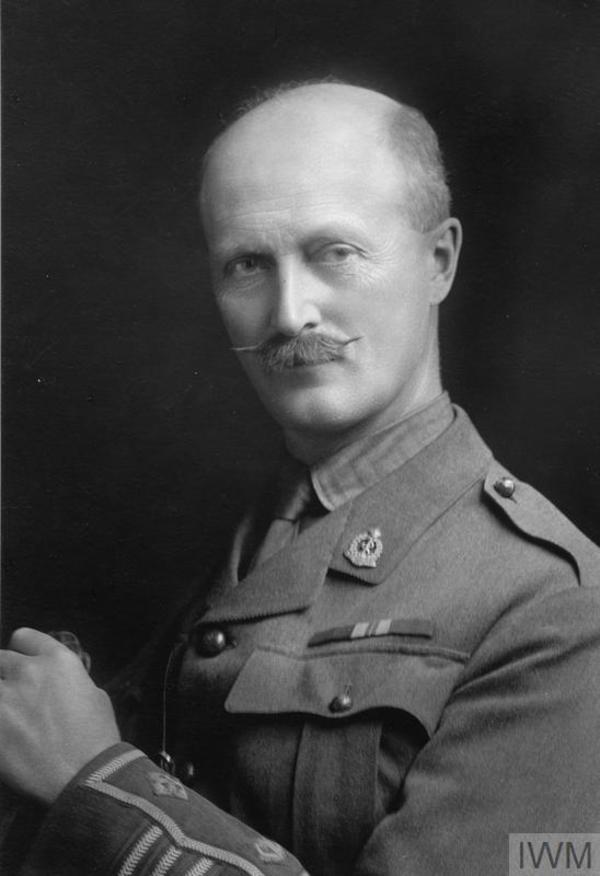

FOTHERINGHAM, JOHN TAYLOR, militia officer, educator, physician, and army officer; b. 5 Dec. 1860 in Kirkton, Upper Canada, son of John Fotheringham and Helen Telfer; m. 30 Dec. 1891 Caroline Jane McGillivray (1860–1921) in Whitby, Ont., and they had two daughters and two sons, one of whom was stillborn; d. 19 May 1940 in Toronto.

J. T. Fotheringham is best known as one of the founders of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC). He grew up in a rural southwestern Ontario community where his Scottish father served as a Presbyterian minister. After attending St Marys Collegiate Institute he studied at Toronto’s University College, and in 1883 he completed his ba with first-class honours in classics. He then left for Grenfell, North-West Territories (Sask.), to work on a farm for the next two years. Upon returning to Ontario he taught classics in secondary schools in Whitby and Brockville, and was an assistant classical and residential master at Upper Canada College in Toronto from 1887 to 1891. During this time he turned to studies in medicine at Trinity Medical College. Soon after graduating with a silver medal in April 1891, he began practising at Toronto General Hospital, the Hospital for Sick Children [see Elizabeth Jennet Wyllie*], and St Michael’s Hospital. He also joined the University of Toronto’s medical faculty and became a lecturer at Trinity Medical College and at the Ontario College of Pharmacy [see Hugh Miller*]. In December he married Caroline Jane McGillivray, whom he called Jennie.

During the 1890s and the first decade of the 20th century medical science was evolving rapidly, as was the professionalization of the Canadian military by Frederick William Borden*, minister of militia and defence. Fotheringham, who had a long association with the militia, would play a role in both fields. From 1879 to 1883 he served with the 2nd Battalion of Rifles (Queen’s Own Rifles of Toronto), commanded by William Dillon Otter*. He was appointed surgeon-lieutenant of the 12th Battalion of Infantry (York Rangers) in 1896 and transferred to the Queen’s Own Rifles with the same rank a year later. In 1899 Borden authorized the formation of the Canadian Militia Medical Service, and Fotheringham was one of the officers commissioned the following year. On 2 July 1904 Ottawa consolidated all military health-care units under centralized command, which led to the establishment of the Permanent Active Militia Medical Corps and the Militia Army Medical Corps. Five years later these bodies combined to form the CAMC.

Fotheringham proved very valuable to the organization: not only did he possess up-to-date medical expertise, but he was also knowledgeable about how best to apply it in a military context. In November 1911, during a public lecture at the University of Toronto titled “The role of medical services in a modern army,” he argued that in wartime a surgeon needs more than medical training: “It is impossible for him to carry out his duties efficiently without a certain general knowledge of military science, especially as regards the administration of an army in the field.” With the threat of war building overseas, he promoted connections between military medical professionals and their counterparts at academic institutions and encouraged civilians to become involved in military issues. Appointed chair of the Canadian Defence League in January 1913, he worked alongside its founding president, William Hamilton Merritt*, and communicated to citizens the need to be prepared for a conflict. Above all, he stressed the importance of preventing disease among soldiers, which had been the leading cause of fatalities in many wars, by instituting sanitation measures and inoculation programs.

Fotheringham showed an aptitude for leadership. In June 1911 he had been sent to England as the medical officer in charge of the unmounted Canadian troops at the coronation of George V. In February 1914 he presided over the annual general meeting of the Association of Officers of the Medical Services, whose members developed a plan for civilians to provide voluntary aid to militia medical services. That year he also served on a committee that was studying venereal disease and public health. He argued for more sex education for soldiers. The outbreak of World War I in August sparked the rapid transformation of the small CAMC, which had only 20 officers, 102 personnel belonging to other ranks, and 5 nursing sisters, into a unit more than 100 times larger. At age 54 Fotheringham enlisted for active service. He was raised to the rank of lieutenant-colonel and appointed assistant director of medical services (ADMS) for Military District No.2, which covered central Ontario, including Toronto. On 25 Feb. 1915 it was announced that Fotheringham would go overseas as the ADMS for the 2nd Canadian Division, commanded by Samuel Benfield Steele*. According to Sir Andrew Macphail, author of the official history of the CAMC, Fotheringham’s appointment was “well received by all ranks and by the public. He had long been in the service; his academic position was assured; his professional status was high; he was trusted as a man of fair mind and generous heart.” While in France, where he was promoted colonel, Fotheringham ministered to evacuees who had been wounded in Belgium during the battles at Saint-Eloi (Sint-Elooi) [see Sir David Watson*] in March and April 1916 and at Mount Sorrel [see Malcolm Smith Mercer*] in June, and during offensives at the Somme in the months following. He was awarded a cmg and twice mentioned in dispatches.

In April 1917 Colonel Fotheringham, who had returned to the CAMC depot in England, was called to Ottawa to reorganize the corps. He was named the director general of medical services (DGMS) and his rank changed to major-general. Macphail would credit Fotheringham with making important adjustments: “In 1917 the policy was adopted of employing officers from overseas to replace those officers who could give only a part of their time to military work.” This measure not only ensured that professional medical officers were aware of military principles and regulations, but it also provided them with a much better understanding of their patients, who were, in turn, more likely to submit to doctors’ orders. Although Fotheringham succeeded in improving administration and shortening patients’ hospital stays, he found aspects of the position challenging and felt he spent much of his time responding to requests he could not fulfil, including demands for increased pay, promotions, and honours. He returned to Toronto in 1919, and the following year he worked with Major-General Gilbert Lafayette Foster, the deputy director of medical services, to plan the CAMC’s post-war reorganization. The need to return so many wounded to Canada, and the effects of the influenza epidemic, delayed demobilization. Public discontent grew and there were negative comments in the press, which Fotheringham found unfair. The medical corps was further strained when, in late 1918, hundreds of its personnel were ordered to accompany a force being sent to Siberia during the Russian revolution. He was also frustrated in his fight against widespread opposition to smallpox vaccinations, particularly from health officials. It was a familiar battle: despite the recent acceptance of germ theory, he had found it difficult to have the men in his battalion inoculated against typhoid early in the war. In September 1920, after six continuous years of military service, he retired from the post of DGMS, to be succeeded by Foster. Within two months Jennie fell ill, and in January she died of cancer of the stomach.

After the war Fotheringham had returned to medicine. He was made head of the outpatient department of St John’s Hospital in Toronto, which was run by the Sisters of St John the Divine [see Sarah Hannah Roberta Grier*], and assisted them in organizing a medical mission at the Church of St John the Evangelist (Garrison Church). In 1924 he became the first chair in the history of medicine at the University of Toronto. That institution and Queen’s University in Kingston had awarded him honorary degrees in 1919, the same year he was appointed honorary surgeon to the governor general of Canada, the Duke of Devonshire [Cavendish]. He continued to serve in that capacity for Lord Byng from 1921 to 1922. Two years later he was gazetted honorary colonel of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps (as it had been redesignated in November 1919). A life member and past president of both the Canadian Military Institute and the Canadian Medical Association, he was also an honorary life member of the Academy of Medicine in Toronto and served as its president in 1923–24. He was made a knight of grace of the Order of St John of Jerusalem in England in 1924.

J. T. Fotheringham retired from St John’s Hospital in 1930 and from his university chair in 1931. He suffered from poor health during his final years and died at home on 19 May 1940 at the age of 79. Following a military funeral at St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, of which he had been a devoted member, he was buried beside his wife in Mount Pleasant Cemetery. In the obituary published in the Globe and Mail on 20 May Major-General John Alexander Gunn* described him as “a great character and a marvelous lecturer. Throughout his life his service to mankind and his beloved Canada was his chief thought.” A tribute in the Journal of the Canadian Medical Association praised Fotheringham as “one of the noblest of men, one of the truest of friends, and one of the richest of minds in Canada.”

John Taylor Fotheringham contributed several articles and book reviews to numerous periodicals, among them the Journal of the Canadian Medical Assoc., the Canada Lancet, the Canadian Practitioner, and the Canadian Pharmaceutical Journal, all published in Toronto. He is the author of The benefits of classical studies for the physician: part of a symposium on “The humanities and the professions” (Toronto, [1900?]).

AO, RG 80-2-0-391, no.040197; RG 80-5-0-198, no.009072; RG 80-8-0-800, no.001427. LAC, R2421-0-0 (John Taylor Fotheringham fonds); RG 150, Acc. 1992–93/166, box 3238-28. Globe and Mail, 20 May 1940. J. G. Adami, War story of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (London, [1918]). Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal, 43 (July–December 1940): 87–88. Canadian who’s who, 1936/37. Andrew Macphail, Official history of the Canadian forces in the Great War, 1914–19: the medical services (Ottawa, 1925). Carman Miller, A knight in politics: a biography of Sir Frederick Borden (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2010). Bill Rawling, Death their enemy: Canadian medical practitioners (Quebec, 2001). The roll of pupils of Upper Canada College, Toronto, January, 1830, to June, 1916, ed. A. H. Young (Kingston, 1917). Bernard Thistlethwaite, Thistlethwaite family: a study in genealogy (London, 1910), 158. The war book of Upper Canada College, Toronto, ed. A. H. Young (Toronto, 1923).

Cite This Article

John MacFarlane, “FOTHERINGHAM, JOHN TAYLOR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fotheringham_john_taylor_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fotheringham_john_taylor_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | John MacFarlane |

| Title of Article: | FOTHERINGHAM, JOHN TAYLOR |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2021 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |