Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

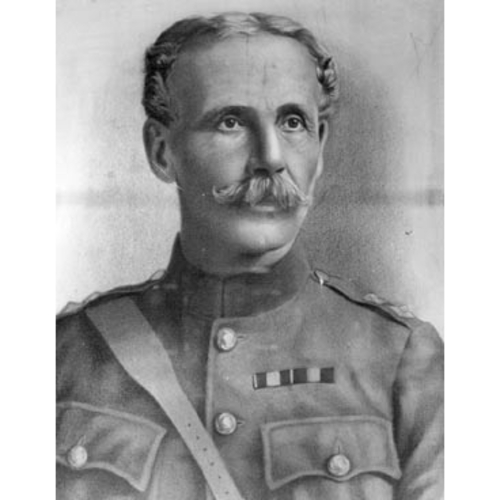

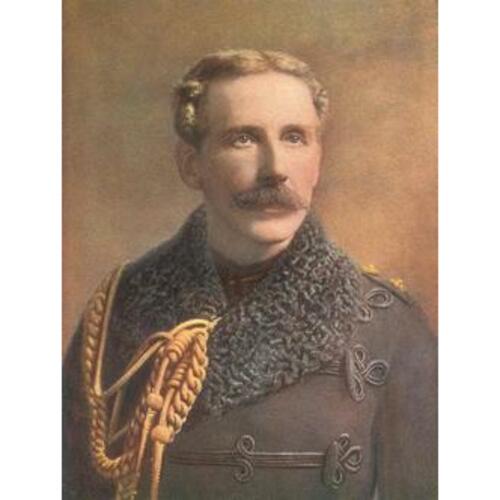

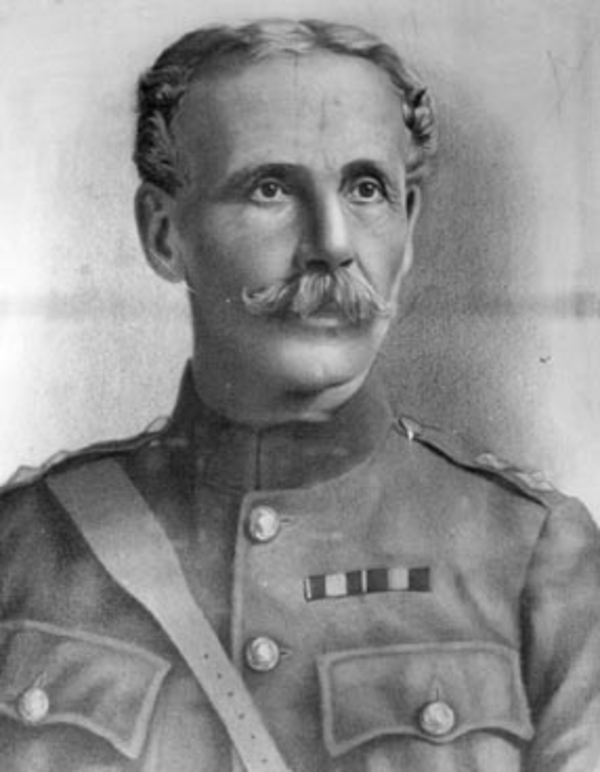

OTTER, Sir WILLIAM DILLON, militia and army officer; b. 3 Dec. 1843 near the Corners (Clinton), Upper Canada, son of Alfred William Otter and Anna de la Hooke; m. 3 Oct. 1865 Marianne Porter in Toronto, and they had a daughter; d. there 6 May 1929.

Will Otter’s paternal grandfather had been a principal of King’s College in London, England, and a bishop of Chichester. In 1841 his father came to the Huron Tract in Upper Canada to seek his fortune; he married, failed as a farmer, and used family influence to obtain a position in Goderich with the Canada Company. The eldest of three sons and two daughters, Will was educated at the Goderich grammar school and, following the family’s move to Toronto in 1854, at the Model Grammar School and Upper Canada College. His father’s financial problems, however, led him as well into the Canada Company as a clerk at age 14.

To Alfred Otter’s dismay, Will found an outlet in amateur theatricals and Toronto’s working-class, volunteer fire brigade. Formation of volunteer militia companies in the wake of the Trent affair [see Sir Charles Hastings Doyle*] encouraged Alfred to force his son to join the high-toned Victoria Rifles, a company of the 2nd Battalion of Rifles (Queen’s Own Rifles of Toronto), commanded by William Smith Durie*. He was initially rejected because of his humble status and friends, and it took all his father’s influence to have him accepted in October 1861. Though his uniform and fees cost him more than a month’s salary, Otter found that military life suited him perfectly. Big, athletic, and handsome, he looked the part; more important, he would recall that “on the first day of my enrolment . . . I became imbued with an ardent desire and love for the order, system and discipline pertaining to and necessary in a military organization.” In the wake of the St Albans raid in October 1864 [see Gilbert McMicken*], he served full-time with an embodied battalion. That December he became a lieutenant – he was formally gazetted on 19 May 1865 – and on 25 August he was confirmed as adjutant of the Queen’s Own. After a winter of alarms and emergency mobilizations, on 2 June 1866 he was one of the raw militiamen who faced a Fenian raid outside Ridgeway [see Alfred Booker*]. On the verge of victory, the militia dissolved in panic. It was Otter’s first lesson on the true importance of discipline.

On 5 Aug. 1865 Alfred Otter had been fired from the Canada Company, probably for drunkenness. Will, now his family’s sole support, continued in the company’s employ. Weeks later he was married at St James’ Cathedral to Marianne, daughter of James Porter*, Toronto’s superintendent of schools. Financially there was no choice for Molly but to begin her married life in the Otter household. Will escaped to the militia and an array of the activities that appealed to Victorian manhood. A founding member of the Toronto Rowing Club in 1865, he stroked the Edrol to the 1867 championship against crews from Ottawa, Toronto, and Lachine, Que. That summer he became the founding president and a leading player of the Toronto Lacrosse Club; in 1868 he was elected president of the National Lacrosse Association. He was named to the board of the Mechanics’ Institute and also became secretary-treasurer of the reorganized Toronto Gymnasium Association and a judge of the Caledonian games. Though he was a poor shot, his organizational ability allowed him to become secretary of the Ontario Rifle Association. As adjutant of the Canadian rifle team at Wimbledon (London) in 1873, he paid his first visit to England and his father’s family.

Such activities satisfied Otter’s inherited yearning for status, but only the militia met his thirst for regularity and discipline. There he thrived and in 1869 was promoted major; still adjutant of the Queen’s Own, he gave it the administrative skills vital for what was as much a social and athletic club as a military unit. Despite shabby uniforms and the collapse of the Toronto drill-shed in March 1870, the battalion increased in size and efficiency. With family responsibilities, debts, and an income of only $1,271 a year, Otter was too poor to aspire to the position of commanding officer, but when the post became vacant in 1875, a year after his promotion to lieutenant-colonel, the officers unanimously selected him.

The fame of the Queen’s Own spread. It was called out during the papal jubilee riots of 1875 in Toronto. When Belleville’s militia refused to crush Grand Trunk Railway strikers, it travelled from Toronto in bitter weather in January 1877 and did the job. Recreational outings to reviews and sham battles also occurred, but Otter preferred practical field-training – when his men and their employers agreed. In 1880 in Toronto he published The guide, a manual for the Canadian militia . . . , a text based on The soldier’s pocket-book for field service (London, 1869) by Garnet Joseph Wolseley*. Largely ignored until approved in England, Otter’s book went through several editions before 1916 and earned him $4,310. It was uncompromising in its insistence on discipline. Some officers, he admitted, believed that severity was inappropriate for militia camps or drill-sheds. “I hold the contrary opinion, . . . the best time to acquire soldierly habits is when quietly parading for weekly drills.” Instead of aping British uniforms, etiquette, and snobbery, he wanted the militia to learn from a tough substance of discipline and subordination.

In 1880 Otter’s career was at a crossroads. He had done all he could with the Queen’s Own; his Canada Company job was stagnant. Militia staff appointments were governed by political patronage. Support for Otter from the Toronto Globe was unhelpful, as was backing from Major-General Richard George Amherst Luard*, the tactless British reformer Ottawa had borrowed to command the militia. Would Otter have to settle for being a superintendent in the North-West Mounted Police or a brigade major in Toronto? Victory in the federal election of 1882 persuaded the Conservatives to keep an old promise: creating a tiny permanent force to run schools for the militia. For the minister, Adolphe-Philippe Caron*, it was a splendid opportunity to reward military-minded political friends, but why not balance the slate with a popular, efficient militia officer? As Otter departed for Wimbledon in June 1883 to command the rifle team, he gave notice to the Canada Company. Late in July he got word from Ottawa of his command of “an Infantry School of Military Instruction” in Toronto at $5.25 a day. After three months’ exposure to British military life, he left in October for Canada, where his move from the Queen’s Own to the Permanent Force had met with widespread approval. He recruited 100 men and established his school at the New Fort (on the grounds of the present-day Canadian National Exhibition); it opened for instruction in April 1884. Luard’s successor, Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton*, brusquely turned down Otter’s offer to lead the Canadian boatmen Britain recruited later that year for its Nile expedition [see Frederick Charles Denison*] – the school would be enough.

That decision did not bar Otter from the militia force hurriedly organized to suppress the Métis defiance at Batoche (Sask.) in 1885 [see Louis Riel*]. On Friday, 27 March, a telegram ordered him to mobilize 80 men from his school and 500 other militiamen and leave for Winnipeg. By noon on Saturday the soldiers had been selected and they soon seethed with impatience, but Otter, mindful of the ill-equipped men who had gone to Ridgeway, spent the weekend scouring Toronto for winter clothing, snow goggles, and boots. Between Dog Lake and Red Rock in northern Ontario, they trudged overland or huddled in open cars on the intervals of track laid by the still incomplete Canadian Pacific Railway. Despite the goggles, Otter would suffer the after-effects of snow-blindness for the rest of his life. From Winnipeg he moved on to Qu’Appelle (Sask.) and then to Swift Current. There he and his men were supposed to board steamers and go down the South Saskatchewan River to join Middleton at Clark’s Crossing, but on 11 April fresh orders came. Panicky appeals from police and settlers at Battleford had gained urgency with the news of the Frog Lake (Alta) massacre [see Léon-Adélard Fafard*]. Otter must march to the rescue; his column set off on the 19th. When the troops reached Battleford on the 24th, politicians and journalists praised Otter for covering 180 miles in under six days. Critics complained that if he had attacked on the night of the 23rd, he might have forestalled a final orgy of destruction.

Battleford’s citizens demanded revenge and Otter’s men agreed. Middleton, his own campaign halted, warned him to stay put but the order came too late. Armed with approval from Edgar Dewdney*, lieutenant governor of the North-West Territories, Otter set out on 31 April with 325 men for the reserve of Plains Cree chief Poundmaker [Pītikwahanapiwīyin*] at Cut Knife Creek. Upon arriving on 2 May, Otter found the camp gone but, as his force went up Cut Knife Hill, his scouts spotted Indian warriors. A battle ensued. When the natives began flanking the hill, Otter realized that he would have to effect a retreat. It was conducted in textbook fashion with few losses, in part because Poundmaker insisted that there had been enough killing. Otter could rationalize his adventure as a “reconnaissance in force”: the Indians had been hurt or they would have pursued. Middleton was not deceived, and Otter’s subordinates denounced him as an inept martinet. Others, however, eager for a Canadian-born hero, turned the battle into a triumph; the Montreal Daily Star urged “Otterism” as a synonym for merciless repression. Otter next led a futile trek north in search of Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa*] and other leaders of the uprising. Left in the west when most of his men returned, Otter could reflect that the best answer to critics of his British-like military professionalism was that he was Canadian-born. Caron’s deputy, Charles-Eugène Panet, took Cut Knife Hill as proof that “Canadians can fight their own battles without foreign help.”

Otter reached Toronto in October 1885. The following spring he assumed, in addition to his responsibilities at the infantry school and without extra pay, the duties of deputy adjutant general for Military District No.2 (Toronto and central Ontario). It was the beginning of a long struggle to infect rural militia with his own strict views on obedience and conformity, and to govern issues otherwise managed as patronage, from camp staff to canteen contracts. He persuaded Colonel Sir Casimir Stanislaus Gzowski* to contribute a trophy for the most efficient regiment in camp. In 1891 he helped launch the Canadian Military Institute and secured municipal funding to move Toronto’s rifle range from the Garrison Common out to Mimico, thus ending a decade of friction between the militia and Torontonians. The following year Middleton’s successor, Major-General Ivor John Caradoc Herbert*, turned the Infantry School Corps into the Canadian Regiment of Infantry. When its four companies gathered for the first time, in 1894 at Lévis, Que., Otter acted as colonel. The next year he would spend six months in England and on the Continent, passing the tests required of a British battalion commander.

At 51, Otter had held the same rank for 21 years and the same salary for 11, and, thanks to his dependent sisters and need to keep up a social position, he was in debt. Earlier, Samuel Hughes, a militia major and old lacrosse friend, had urged his claims to be adjutant general, the highest position available to a Canadian. But when a vacancy occurred in early 1896, following the retirement of Walker Powell*, Hughes, then a Tory mp, regarded Otter’s “grittish proclivities” as a barrier. The Liberals on the other hand suspected him of being a Tory appointee, favoured in April 1896, just before the federal election, with yet another unpaid title, inspector of infantry. Otter survived the change of government and became an asset to Wilfrid Laurier*’s reform-minded minister of militia and defence, Frederick William Borden*, and to the latest British commander of the Canadian militia, Major-General Edward Thomas Henry Hutton. Otter was unimpressed by his self-aggrandizing new chief. Though Hutton named him to command a Canadian contingent in the event of war in South Africa, when he finally presented a plan to Borden, Hutton explained that he, not Otter, would command. “You will, I think, be a gainer in the end,” he told Otter in September 1899.

He was. The government ignored Hutton’s plan and British guidelines. On 13 October Otter was given command of the contingent authorized for South Africa, to be recruited from across Canada and called the 2nd (Special Service) Battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry. Instead of a nominal command, Otter would have a fighting unit. In a frantic two weeks more than a thousand men were enlisted; political squabbles over the appointments of officers continued until the troopship Sardinian sailed on 30 October. Determined that his Canadians would acquit themselves like soldiers, Otter began basic training on the decks of this ill-adapted cattle-ship. Used to easygoing militia standards, his subordinates grumbled and acted out regional jealousies.

By the time Otter reached Cape Town on 29 November, he knew how badly the war was going for the British. Sent to Lord Methuen’s force on the Modder River, the Canadians were supplanted in action by a veteran British battalion. They endured two more months of drill, marching, and sentry duty at Belmont under the grizzled martinet and a blazing sun. Otter had hoped to use his service to win promotion in the British army but he soon realized that he had little hope against nimble careerists half his age. Instead, as the first Canadian force commander in battle, he found himself overworked, with masters in Ottawa as well as in the field. Hardened by training, the Canadians finally passed muster with Lord Roberts, the British commander, and were sent to join Colonel Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien’s 19th Brigade.

On 12 Feb. 1900 a train took Otter’s battalion to Graspan, where it became part of a plan to trap the army of Boer commander Piet Arnoldus Cronje. Next day the Paardeberg campaign began with a march to Ramdam; of 896 Canadians, 50 dropped out from thirst and heat. More exhausting marches followed, and a few began to appreciate Otter’s attempt to prepare them. On the 18th the Canadians reached Paardeberg Drift, crossed the Modder, and advanced on Cronje’s defences. Boer rifles soon forced them to seek shelter; in the afternoon, after disparaging the raw colonials, a British battalion attacked through them. The Canadians rose and charged, at a cost of 21 lives, the bloodiest Canadian encounter since the War of 1812. The battle became a siege. On the 27th the Canadians launched a night attack: shooting began, the troops dropped for cover, and a few minutes later most fled to their old trenches. A furious Otter faced the third retreat of his career. On the right, however, the better part of two companies stayed put. As dawn broke the Boers started to surrender. Most imperial soldiers remembered that it was Majuba Day, anniversary of the Boers’ humiliating defeat of the British in 1881. The night-time panic forgotten, Otter’s Canadians became the ideal symbols of a great victory for the British empire.

More weary marching took the regiment to Bloemfontein, where Roberts planned to rebuild his army. Cold and rain turned the Canadian bivouac into a swamp; eight died in an army-wide epidemic of enteric fever. Seated under a wagon, Otter dealt with a flood of mail from Canada, some of it censuring his harsh discipline. (At home he could count on powerful friends to keep critical letters out of the press.) On 21 April the advance resumed. At Israel’s Poort on the 25th, Boer fire drove the battalion’s front line to ground. Noting some men slipping back, Otter strode out to stop them. Hardly had he returned when a bullet struck him in the face. He rejoined his battalion on 26 May, in time to lead it at the battle of Doornkop and to march in triumph through Pretoria on 5 June.

By tradition the war should now have been won. Instead, Otter’s men faced dispiriting months of guard duty interspersed with futile marches against mounted commandos. Most looked forward to going home when their year was up. Convinced that victory was near, Roberts asked Otter to keep his men a few more weeks. What answer could he give but yes? Many, feeling no such call, went home, armed with a further grievance against their commander. Those who stayed returned as heroes via England, where they were inspected by Queen Victoria on 30 Nov. 1900. Otter’s friends in Toronto, determined to flatten his critics, staged a huge banquet for him on 28 December. Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot*] welcomed him as “Canada’s best soldier.” Otter modestly insisted that, with such excellent material, it had been easy to form “one of the most efficient battalions which tramped the veldt.” Earlier the government had changed the Militia Act to allow him and other senior officers to become full colonels (official notice reached Otter in South Africa on 9 October). A cb followed at the end of 1901. His critics were not silenced but they remained anonymous. Once again nationalism served a man who had tried to make Canadians into a good British battalion. “He is a product of the Canadian Militia,” declared the Canadian Military Gazette (Montreal), “and we should all stand by him and feel proud of him.”

Although some Canadians agreed with Sam Hughes that the war had been a triumph of sharpshooting amateurs over blinkered professionals, most believed that active service had made Canadian soldiers as good as the British. Why then should British officers continue to hold key positions in the militia when officers such as Otter were available? The minister, Borden, was sympathetic but cautious and devoutly imperialist, and Otter continued in command of Military District No.2 at a higher salary. With financial advice from Henry Mill Pellatt*, the business-minded commander of the Queen’s Own, Otter was never again poor; by 1902 he had $1,000 a year in investment income. In 1901–2 he was part of a committee that adopted the infamous Ross rifle, an achievement he never recorded in his otherwise voluminous personal records.

As in South Africa, Otter’s enforcement of discipline and regulations made him unpopular with the largely Conservative officers of central Ontario’s militia units. In unrecorded but remembered speeches at reviews and inspections, he attacked the lack of control and subordination in the militia. At 60 he was overage and a Tory victory in 1904 might have ended his career. Instead, he became a beneficiary of amendments to the Militia Act earlier that year, whereby the British general officer commanding was replaced by a militia council in which the senior officer would be chief of the general staff (CGS), and not necessarily British. Eastern Canada was divided into commands and, after an effort to move him to Montreal, Otter took over western Ontario. In a period of such dramatic reform and expansion, his energy and expectations had fuller scope than ever. At the same time the experience of South Africa and the growing threat of war in Europe had fed a British desire to integrate dominion forces. In 1907 an imperial conference agreed to the standardization of doctrine and training. To keep key Canadian positions under its control, the War Office offered Otter a brigade at Aldershot. As he weighed this offer, the death of Brigadier-General Beaufort Henry Vidal* in March 1908 allowed the government to promote its British CGS to the higher post of inspector general and appoint Otter CGS with the rank of brigadier-general. Canadians were delighted. One of their own had been offered a British brigade but had refused it in order to become Canada’s top general. Old antagonisms were forgotten in the chorus of praise. Few noted that Otter’s predecessor, Major-General Percy Henry Noel Lake*, continued as inspector general and Canada’s senior military adviser.

Otter’s first task was to organize a vast military review for the celebration of Quebec City’s tercentenary. The 12,422 men and 2,134 horses assembled on 24 July 1908 outnumbered the combined forces of Wolfe* and Montcalm*. The assembly was also a climax of military spending. The $1-million annual budget of the 1867–96 period was long forgotten. By 1908–9 the militia department had $6.5 million, with pressure to spend more. However, the prosperity of the Laurier era was running out. At the end of 1908 the Militia Council was told that it had to find $1 million in cuts. The public and the militia clamoured to reduce staff and the Permanent Force rather than summer militia camps. To inspect what defences Canada did have, Otter toured the country in 1909; at Petawawa, Ont., he watched the new Canadian aircraft Baddeck No.1 take off but “did not care to express an opinion.” The following year he succeeded Lake as inspector general, an appointment that led to his promotion to acting major-general in November 1910. (A British general became CGS and the government’s senior military adviser and no Canadian officer would have this double role until 1920.)

On 10 Oct. 1911 the Conservatives formed a government. As minister of militia, Sam Hughes soon ran foul of the senior British officers. One result was Otter’s confirmation as a major-general in July 1912, but almost immediately he heard that he was to be retired on 1 December. Since he was 68 the move was hardly overdue, though he was bitter at being denied a full four-year term as inspector general and the honours that usually marked a distinguished career. His final report, published in January, was a trenchant attack on most of Hughes’s policies; in Otter’s opinion, militia camps and provisional schools were inadequate, instructors were sometimes unqualified, complacency pervaded the militia, and the Permanent Force was being seriously neglected. Otter was in England when he learned that the governor general, the Duke of Connaught [Arthur*], had prevailed over his ministers and that he would be made a kcb. He was present at Buckingham Palace for his investiture on 11 June 1913.

Back in Canada, Otter was available to speak on military preparedness, as hard times and Hughes’s excesses helped drain away an earlier mood of militarism. World war, on 4 Aug. 1914, restored it. Otter felt useless: home guards and the Red Cross Society heard his advice on military needs but ignored it. Lacking direct threats, Canadians turned on the aliens in their midst, forcing the government to intern hundreds of Germans and thousands of Polish and Ukrainian labourers who happened to be Habsburg subjects [see William Perchaluk*]. Minister of Justice Charles Joseph Doherty* summoned Otter to Ottawa on 30 October and invited him to take charge of internment operations. Interrupted only by his wife’s death in November, he worked tirelessly, establishing camps from Fort Henry near Kingston, Ont., to Nanaimo, B.C. First-class internees, who could not be expected to work, were distinguished from second-class ones, who would labour at such projects as clearing bush at Kapuskasing, Ont., or developing the national park at Banff, Alta. In addition, Otter consolidated camps, released internees needed for war work, and protected camp commanders who shared his dedication to order. The postwar anti-Bolshevik panic brought new prisoners to Kapuskasing, and not until the end of 1919 would the last camps be cleared.

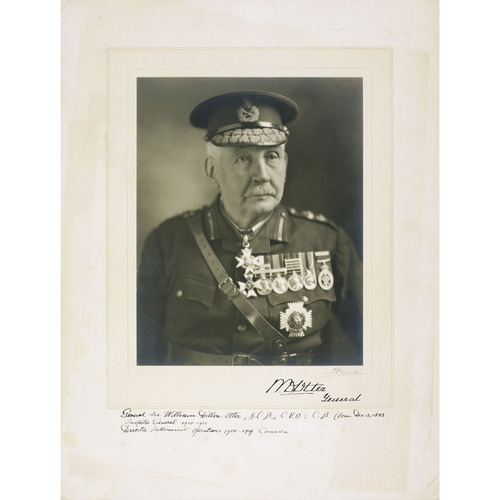

In 1919 Otter assumed another chore: heading the reorganization committee formed to combine the old militia regiments and the new units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Though most of the work would be done by younger officers, Otter provided experience. He told wrangling colonels of the public feeling that there should be no militia at all. They were unmoved, politicians backed them, and Otter’s committee would be blamed for the swollen militia organization that was halved in 1936. He also sat on a committee to choose officers for the Permanent Force. His services ended in June 1920 with three months’ pay and virtually no public notice. In 1921 Major-General James Howden MacBrien*, his protégé and postwar CGS, reminded the newly elected Liberal government that Otter had never been transferred to the retired list. The error was graciously remedied on 9 March 1922 by his promotion to general, making him the second Canadian in that rank after Sir Arthur William Currie*. On 7 June 1923 the University of Toronto granted him an honorary lld at a convocation dominated by returned soldiers. He was declining. On 27 Nov. 1927 veterans of the Queen’s Own fêted him at a banquet. For once he was almost incoherent. Early in 1928 he stumbled on a streetcar and broke his ankle; when he seemed ready to walk, he relapsed. On 6 May 1929 his nurses found him dead.

Militia contemporaries called Otter “the Father of the Force.” He was its military conscience and disciplinarian and a remorseless critic of its failings. His faith in discipline and order found few echoes among Canadians, but they were qualities that determined victory or defeat. Otter had learned the lesson at Ridgeway.

Almost all the references for this account can be found in Desmond Morton, The Canadian general: Sir William Otter (Toronto, 1974). Otter’s papers are in NA, MG 30, E242. A large collection of scrapbooks, papers, and family bibles is in the possession of the author. The other main secondary sources are Carman Miller, Painting the map red: Canada and the South African War, 1899–1902 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1993), and S. J. Harris, Canadian brass: the making of a professional army, 1860–1939 (Toronto, 1988).

Cite This Article

Desmond Morton, “OTTER, Sir WILLIAM DILLON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/otter_william_dillon_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/otter_william_dillon_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Desmond Morton |

| Title of Article: | OTTER, Sir WILLIAM DILLON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |