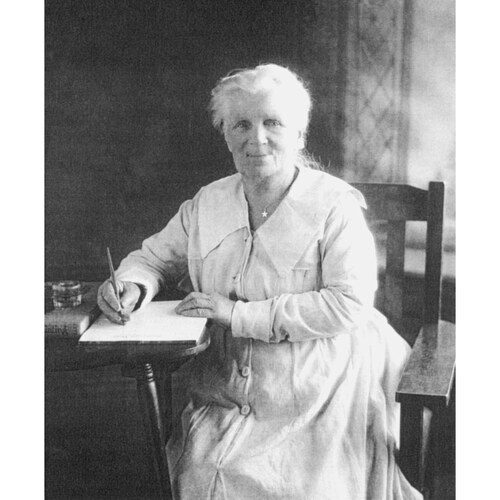

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Moir, Susan Louisa (Allison), teacher, pioneer rancher, storekeeper, historian, and author; b. 18 Aug. 1845 in Colombo, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), third child of Stratton Moir and Susan Louisa Mildern; m. 3 Sept. 1868 John Fall Allison (d. 1897) in Hope, B.C., and they had 14 children; d. 1 Feb. 1937 in Vancouver.

Susan Louisa Moir was born in Ceylon, the daughter of a coffee planter of Scottish origin who died when she was four years old. Her mother then took Susan, her brother, Stratton, and her sister, Jane Shaw, to live with relatives in Britain. Although her income was limited, Mrs Moir sent the children to London schools. Young Susan developed a love of learning and family chronicles. In 1855 Susan’s mother married Thomas Glennie. He had inherited and spent several fortunes, and in 1860 he decided to seek another as a gentleman farmer in the colony of British Columbia, where he hoped to strike it rich during the gold rush. Susan, her mother, and her sister accompanied him.

According to Susan’s recollections, both she and Jane were “keen for adventure.” They were fortunate that the people they met at the mining centre of Hope – including William Charles* of the Hudson’s Bay Company and his wife, Mary Ann, a member of the Birnie fur-trading family – helped them adapt to the frontier. Spendthrift Glennie failed as a farmer. After Jane’s marriage to surveyor Edgar Dewdney* in March 1864, Glennie deserted the family.

In 1865 Susan and her mother left the declining town of Hope for Jane’s home in New Westminster. Susan found employment in Victoria as a governess for Amelia Birnie, sister of Mary Anne Charles and wife of John McAdoo Wark. Thanks to a small legacy, she then spent a season in New Westminster. Her brother, learning of his mother and sister’s financial difficulties, sailed for British Columbia but died en route in October 1866. The following year Susan and her mother returned to Hope to open a school. Susan later noted that she “did not like teaching but it helped out my small income.”

Soon Susan and John Fall Allison, a rancher 20 years her senior, were courting. The English-born Allison had lived in the eastern United States before venturing first to the goldfields in California and then to British Columbia. Allison prospected and surveyed while starting a ranch in the Similkameen valley. He visited Hope when he drove his cattle west to markets. Marriage to Allison in 1868 brought Susan face to face with some of the realities of pioneering as well as with the romance of what she would call “the wild, free life.” There were few settlers in the southern interior of the colony, and none near their ranch. When John left on cattle drives, Susan took over as manager of the ranch and looked after the trading post and post office he had set up in their home. She learned Chinook Jargon [see Jean-Marie-Raphaël Le Jeune*] and made friends among Similkameen employees and neighbours. During the period from July 1869 to August 1892, she bore 14 children. Although she was assisted by Indigenous women during childbirth and in rearing them, she schooled most of them herself.

In the 1870s John Allison and his partner, Silas W. Hayes, moved the ranch headquarters to the west bank of Okanagan Lake. There, at Sunnyside Ranch, Susan enjoyed participating in activities with her children and listening to stories told by the Okanagan, also known as Syilx. She did have some worrisome times during the Indigenous unrest of the late 1870s. Although her husband had good relations with First Nations leaders and advocated that the government settle the land question [see Gilbert Malcolm Sproat*], as a jp from 1876 he would be associated by Indigenous people with government officials such as Judge John Carmichael Haynes*. In addition, she was concerned about the predations of outlaw Allan McLean* and his brothers.

Financial losses and the breakup of his partnership with Hayes in the early 1880s led John Allison to sell his Okanagan holdings and move back to the Similkameen valley. He opened a trading post, as he had when he first settled there, and Susan, who disliked keeping the store, noted in her recollections that she was “condemned” to this task. She coped with crises, including a fire in 1882 that destroyed the ranch house and a flood in 1894 that destroyed it again, together with 13 other buildings. Despite such difficulties, the Allisons received distinguished visitors with courtesy and hospitality, among them the American general William Tecumseh Sherman, who passed through the area in 1883. Susan had little time to record the family chronicles or the Similkameen stories with which she entertained her children. Fortunately, the Dewdneys settled in Victoria in 1892 and assisted the Allisons by boarding some of their children, who were sent there to continue their education.

By the time John Fall Allison died in 1897, mines and towns (Granite Creek and Princeton) had developed near the ranch. Susan dealt with ongoing challenges: the lack of a rail connection, retail competition, the failure of mining projects, and the departure of her elder sons.

Soon after her marriage Susan had turned to writing as a substitute for companionship during her husband’s absences. She noted stories, incidents, and Indigenous customs in her account books. Yet it was only later in life that she considered submitting them to a wider audience. Her first publications drew on her associations with First Nations peoples. In an article printed in the British Association for the Advancement of Science’s Report of the sixty-first meeting in 1892, she expressed her concern that the Similkameen people had “deteriorated” in the “last twenty years, and [were] rapidly becoming extinct.” She did not mention their ongoing resistance in the lands issue, nor did she hint, as she would in her recollections, that her husband had had relationships with Similkameen women, that his mixed-race children were acknowledged locally as Allisons, and that she regarded one of them, Lily, as a very dear friend. In a second and longer article published in 1892 in the Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Susan described the Similkameen people, not as members of a dying community but as “proud and independent…. They have their own farms on the reserve and employ white and Chinese labour.”

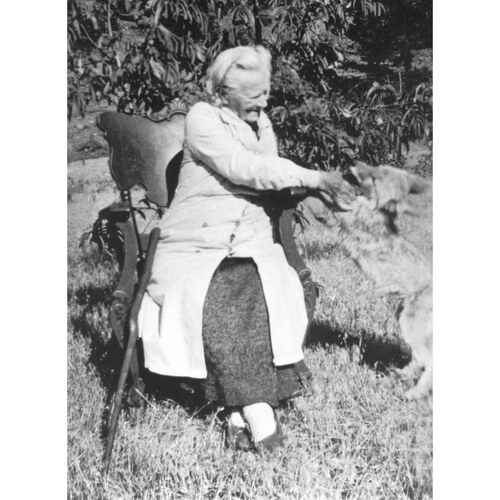

Susan Allison used the pseudonym Stratton Moir in her publication of In-cow-mas-ket (Chicago, 1900), a narrative poem based on Similkameen history. She put her own name on later prose accounts of Indigenous life and early European settlement that appeared in the Similkameen Star (Princeton), and on her telling of Indigenous legends in the Reports of the Okanagan Historical and Natural History Society (shortened to the Okanagan Historical Society from its sixth report in 1935). After she retired to Vancouver in 1928, an editor at the Vancouver Daily Province, Cecil Oscar Scott, encouraged her to write her memoirs and arranged for their serialization in 13 issues of the paper’s Sunday edition in 1931. They attracted wide attention because of their literary quality and interesting descriptions of pioneer life.

Before she died in 1937, Allison had earned a reputation as a local historian; she had been named honorary president of the Similkameen Historical Association in 1932 and the Okanagan Historical Society in 1935. Her work inspired author Dorothy Livesay* and musician Barbara Pentland* to collaborate on an opera, The lake, which was completed in 1952 and first performed two years later. Historian Margaret Anchoretta Ormsby’s 1976 edition of A pioneer gentlewoman in British Columbia: the recollections of Susan Allison brought Allison’s writing to the attention of scholars in anthropology, history, and literature. Like Ormsby, they recognized the book as one of the few primary sources about women’s experiences in 19th-century British Columbia, and one of the few to discuss the lives of First Nations people. Some current scholars discount Allison as a white colonial settler, but others recognize that for her time she was remarkable – for her friendships with the Similkameen and Okanagan peoples, and her promotion of their histories. Scholars are able to draw on ethnohistorical and literary studies to explore her recounting of Indigenous stories, her pioneer recollections, and her unpublished sketches, which can be compared with the writings of Emily Pauline Johnson* and Susanna Moodie [Strickland*]. Allison’s longer 1892 article, brought to the attention of historians in 2000, further offers the opportunity to compare her ethnological reports with those of her British and Canadian contemporaries. In 2007 the Canadian government declared her a national historic person.

The memoirs of Susan Louisa Moir (Allison) were published as A pioneer gentlewoman in British Columbia: the recollections of Susan Allison, ed. M. A. Ormsby (abridged ed., Vancouver, 1976). Allison is the author of “Account of the Similkameen Indians of British Columbia,” British Assoc. for the Advancement of Science, Report of the sixty-first meeting (London, 1892), 815. A longer article under the same title appeared in the Journal (London) of the Anthropological Instit. of G.B. and Ire., 21 (1892): 305–18. She published In-cow-mas-ket (Chicago, 1900) under the nom de plume Stratton Moir. She also wrote “The Similkameen Indians,” Similkameen Star (Princeton, B.C.), 20 March 1912; “Early history of Princeton,” Princeton Star, 5, 19 Jan., 9, 23 Feb., 9 March 1923; “Some recollections of a pioneer of the ‘sixties,’” Vancouver Daily Province, 22 Feb., 1, 8, 15, 22, 29 March, 5, 12, 19, 26 April, 3, 10, 17 May 1931; and a four-part article, “Allison Pass memoirs,” Canada West Magazine (Summerland, B.C.), 1 (1969), no.4: 25–28; 2 (1970), nos.1–3: 19–23; 20–23; 18–21. She wrote three articles for Annual reports (Vernon, B.C.) of the Okanagan Hist. and Natural Hist. Soc.: “Ne-hi-la-kin: a legend of the Okanagan Indians written fifty-two years ago,” 2 (1927): 6–8; “The big men of the mountains: a legend of the Okanagan Indians written fifty-two years ago,” 2: 8–11; and “The aurora in the Okanagan,” 5 (1931): 21–22.

BCA, GR-2080; MS-2692; GR-2951, no.1937-09-525054; GR-3044, no.5-A/A-1. City of Vancouver Arch., AM54-S17-M201 (Major Matthews coll., newspaper clippings, Mrs. Susan Allison file); FC 3823.1 .A45 M44 (Memoirs of Mrs. S. L. Allison, British Columbia, 1860-1870-1880). Greater Vernon Museum and Arch. (B.C.), MS 185; 1997.004 (Dr. Margaret Ormsby fonds). Penticton Museum and Arch. (B.C.), Allison family fonds: 1849–1889. Univ. of B.C. Arch. (Vancouver), Margaret Ormsby fonds, box 4, file 4. Mainland Guardian (New Westminster, B.C.), 9 Oct. 1875. Princeton Star, 15 Aug. 1935. Vancouver Daily Province, 2 Feb. 1937. Jean Barman, “Lost Okanagan: in search of the first settler families,” Okanagan Hist. Soc., Report, 60 (1996): 8–20; Sojourning sisters: the lives and letters of Jessie and Annie McQueen (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 2003). K. [A.] Bridge, By snowshoe, buckboard and steamer: women of the frontier (Victoria, 1998). Creating historical memory: English-Canadian women and the work of history, ed. Beverly Boutilier and Alison Prentice (Vancouver, 1997). F. [E. M. A. Agassiz] Goodfellow, Memories of pioneer life in British Columbia (Wenatchee, Wash., 1945). J. C. Goodfellow, “Mrs. S. L. Allison,” British Columbia Hist. Quarterly (Victoria), 1 (1937): 130–31. [R.] C. Harris, Making native space: colonialism, resistance, and reserves in British Columbia (Vancouver and Toronto, 2002). Douglas Hudson, “The Okanagan Indians,” in Native peoples: the Canadian experience, ed. R. B. Morrison and C. R. Wilson (Toronto, 1986), 445–66. A. [L.] Laforet and Annie York, Spuzzum: Fraser Canyon histories, 1808–1939 (Vancouver, 1998). Okanagan sources, ed. Jean Webber and En’owkin Centre (Penticton, 1990). Okanagan women’s voices: Syilx and settler writing and relations, 1870s–1960s, ed. J. C. Armstrong et al. (Penticton, 2021). Clive Phillipps-Wolley, A sportsman’s Eden (London, 1888). Paige Raibmon, Authentic Indians: episodes of encounter from the late-nineteenth-century northwest coast (Durham, N.C., and London, 2005). A rich and fruitful land: the history of the valleys of the Okanagan, Similkameen and Shuswap, [comp. Jean Webber] (Madeira Park, B.C., 1999). Harry Robinson, Write it on your heart: the epic world of an Okanagan storyteller, comp. W. C. Wickwire (Vancouver, 1989). Veronica Strong-Boag and Carole Gerson, Paddling her own canoe: the times and texts of E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake) (Toronto, 2000). R. J. Sugars, An Okanagan history: the diaries of Roger John Sugars, [ed. J. A. Sugars] (Westbank, B.C., 2005). Duane Thomson, “The response of Okanagan Indians to European settlement,” BC Studies (Vancouver), no.101 (spring 1994): 96–117. Duane Thomson and Marianne Ignace, “‘They made themselves our guests’: power relationships in the interior plateau region of the Cordillera in the fur trade era,” BC Studies, no.146 (summer 2005): 3–35. H. E. White, “General Sherman at Osoyoos,” Okanagan Hist. Soc., Report, 15 (1951): 44–66. Wendy Wickwire, At the bridge: James Teit and an anthropology of belonging (Vancouver and Toronto, 2019).

Cite This Article

Jacqueline Gresko, “MOIR, SUSAN LOUISA (Allison),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/moir_susan_louisa_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/moir_susan_louisa_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jacqueline Gresko |

| Title of Article: | MOIR, SUSAN LOUISA (Allison) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | April 25, 2025 |