Source: Link

WILSON, THOMAS EDMONDS, police officer, packer, mountain guide, hunter, trapper, prospector, outfitter, and rancher; b. 21 Aug. 1859 in Bond Head, Upper Canada, son of John Wilson and Eliza Edmonds; m. 19 Oct. 1885 Minnie McDougall, niece of George Millward McDougall* and cousin of John Chantler McDougall*, in Edmonton, and they had two sons and four daughters; d. 20 Sept. 1933 in Banff, Alta.

Tom Wilson attended local schools and graduated from the grammar school in Barrie, Ont., in 1875. Stirred by wanderlust, he left to seek adventure in Detroit, Chicago, and Sioux City, Iowa. In 1878 he returned home and that October he enrolled in the Ontario Agricultural College in Guelph and joined the Volunteer Militia Field Battery of Ontario, made up of OAC students. He left the college in 1879, possibly without graduating, and signed on with the North-West Mounted Police, who were recruiting for their undermanned western posts. He began his service at Fort Walsh (Sask.) on 22 Sept. 1880 and was primarily engaged in observing the activities of Sitting Bull [Ta-tanka I-yotank*] and his followers, who had come to Canada after the battle of the Little Bighorn River. Later, in the spring of 1885, he would join the forces of Samuel Benfield Steele* to pursue Cree chief Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa*] in the aftermath of the North-West rebellion [see Louis Riel*].

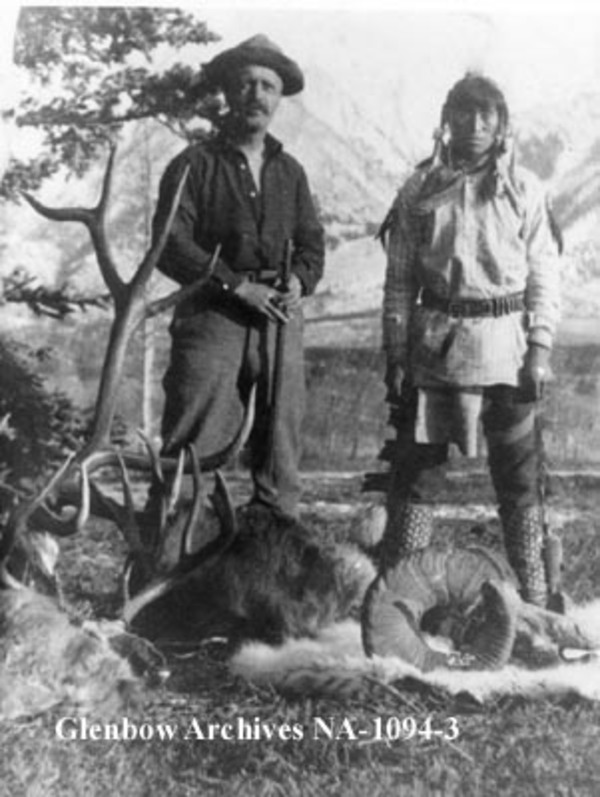

Early in 1881 Wilson heard that the Canadian Pacific Railway was hiring men at Fort Benton, Mont., to assist in surveying a route for its line through the Rocky Mountains. Leaving the police force in May 1881, he headed for Fort Benton and was hired as a packer for Albert Bowman Rogers*, the engineer in charge of mountain-location work. Wilson soon found himself at the survey headquarters at the foot of the Rockies packing supplies on up to 80 Indian-bred horses that travelled to the survey camps. Rogers, a tough, no-nonsense American, appeared there in July after an unsuccessful attempt to find a pass through the rugged Selkirk Mountains. He wanted a personal attendant. When no one stepped forward, Wilson volunteered. This difficult job prepared him well for the life of a mountain guide. Over the next few years he would accompany Rogers on many of his explorations; he would also carry out expeditions on his own. These assignments gave him a familiarity with the mountains that otherwise would have been impossible to acquire. In between surveying seasons he hunted, trapped, and prospected.

His trailblazing took Wilson to several places previously known only to natives. His most famous “discovery” was made early in the summer of 1882 when he was camped at the mouth of the Pipestone River in what is now southwestern Alberta. Hearing the sound of avalanches, he asked a Stoney Indian, Edwin Hunter, known as Goldseeker, to lead him to their source, which Hunter said was near “the Lake of the Little Fishes.” After bushwhacking through some heavy timber the two arrived on the shore of a magnificent piece of water. Wilson, who claimed to be the first white man to see the lake, described the scene:

As God is my judge, I never in all my explorations saw such a matchless scene. On the right and the left forests that had never known the axe came down to the shores, apparently growing out of the blue and green waters. The background, a mile and a half away, was divided into three tones of white, opal and brown where the glacier ceased and merged with the shining water. The sun, high in the noon hour, poured into the pool which reflected the whole landscape that formed the horseshoe.

He called this “pool” Emerald Lake, but in 1884 one of Rogers’s assistants, P. K. Hyndman, named it Lake Louise in honour of Princess Louise, wife of the governor general, the Marquess of Lorne [Campbell*] (Wilson had worked for Lorne’s expedition to the prairies in 1881). Another beautiful lake located by Wilson in 1882, in what is now British Columbia’s Yoho National Park, ultimately bore the name Emerald Lake.

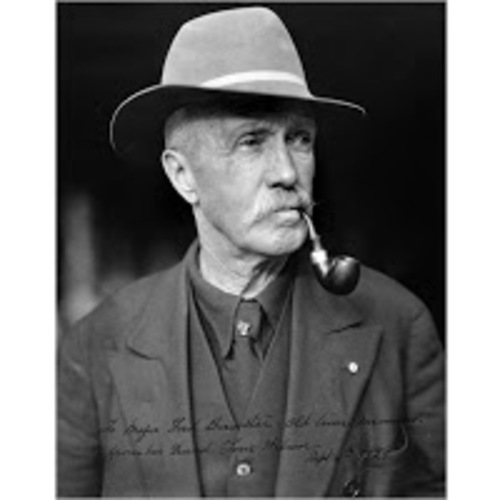

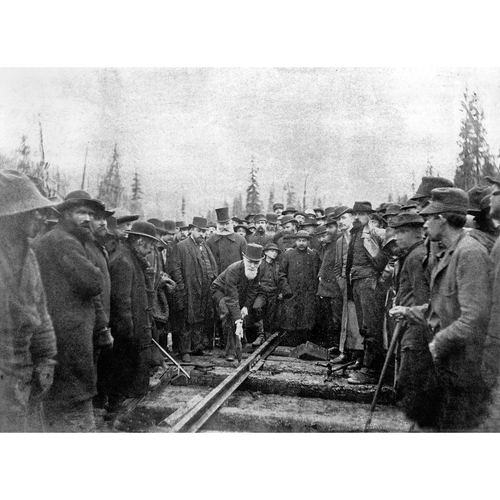

His finding of Lake Louise would bring him much notoriety, and he would use it to good advantage after the completion of the CPR in 1885. He married in October of that year and settled with his wife at Morley (Alta). The following month Wilson, a long-faced man with a large, drooping moustache who was seldom seen without a broad-brimmed Stetson hat, appeared in the famous photo of the driving of the CPR’s last spike at Craigellachie, B.C., a ceremony that the general manager, William Cornelius Van Horne*, had decreed could be attended only by those who had worked for the railway or had paid their own way.

The CPR opened up the west to tourists, a national park was established around Banff in 1887, and Wilson was there to offer guiding and outfitting services to the numerous international visitors coming by train to explore, fish, hunt, and in particular to climb some of the area’s fine peaks; he would lead several first ascents, including those of Molar Mountain (1901) and Crowsnest Mountain (1904). Becoming a virtual encyclopedia on the Rockies, he was frequently hired by the CPR to blaze new trails and to supply important parties. He worked as a packer for the Dominion Lands Survey [see Édouard Deville*] from 1889 until 1893, the year he brought his family from the homestead at Morley to settle in Banff. His contribution to opening up the Rockies was recognized in 1898 by British climber John Norman Collie, who chose the name Mount Wilson for the huge peak first ascended by James Outram* in 1902.

Wilson gained the coveted outfitting concession for the CPR’s mountain hotels in 1902, and he built up his trail business while diversifying into a horse ranch and trading post on the Kootenay Plains west of Banff. He employed several guides who would become famous, among them Bill Peyto, Jimmy Simpson, and Fred Stephens. Competition from a similar venture led by Jim and Bill Brewster and the decisions of some of his best men to go into business for themselves led Wilson to sell his outfitting interests to his partner, Robert E. (Bob) Campbell, in 1904. In March 1906 he attended the founding meeting of the Alpine Club of Canada in Winnipeg and was chosen to be on its advisory committee. He continued to work for much of each year at the Kootenay Plains ranch until he froze his feet while snowshoeing to Banff to visit his family at Christmas 1908. Some of his toes had to be amputated.

This injury forced him to abandon active trail life. Wilson served for a number of years as Banff’s police magistrate and as a justice of the peace until he moved to Vancouver and then to Enderby in the Okanagan in 1920–21. He was present for the unveiling of a plaque honouring him as “Trail Blazer of the Canadian Rockies” in July 1924; the event was part of the inaugural ride of the CPR-sponsored Trail Riders of the Canadian Rockies. (The plaque would eventually be moved from the mouth of the Yoho valley to Wilson’s grave in Banff.) Finding the lure of the mountains too strong, he returned to Banff in 1927. For the final six years of his life Tom Wilson was employed by the CPR to regale tourists and journalists at the Banff Springs Hotel [see Bruce Price*] and Château Lake Louise with stories of his discovery of Lake Louise and “the good old days” on the trail.

Thomas Edmonds Wilson’s reminiscences, as told to W. E. Round and edited by H. A. Dempsey, were published as Trail blazer of the Canadian Rockies (Calgary, 1972).

GA, M 1321, M 1322, M 1323, M 1324, M 3178, M 4223, M 6326. Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Arch. and Library (Banff, Alta), M10/V701 (Tom Wilson family fonds). E. J. Hart, Diamond hitch: the early outfitters and guides of Banff and Jasper (Banff, 1979). W. F. E. Morley, “Tom Wilson of the Canadian Rockies,” Alberta Hist. (Calgary), 54 (2006), no.1: 2–9.

Cite This Article

Edward J. Hart, “WILSON, THOMAS EDMONDS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wilson_thomas_edmonds_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wilson_thomas_edmonds_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Edward J. Hart |

| Title of Article: | WILSON, THOMAS EDMONDS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2014 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |