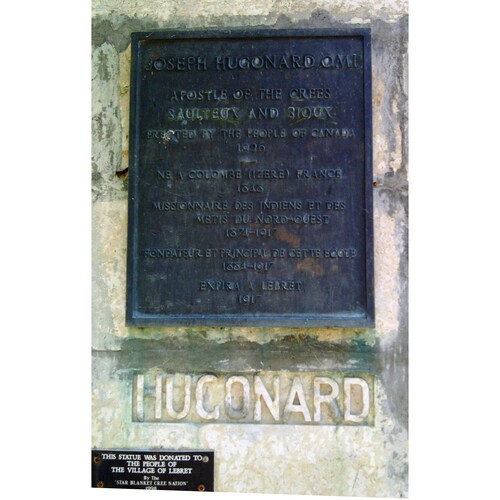

HUGONARD, JOSEPH (until mid-life he signed Hugonnard), Roman Catholic priest, Oblate of Mary Immaculate, and educator; b. 1 July 1848 in Colombe, France, son of Jean Hugonnard and Françoise Rival; d. 11 Feb. 1917 in Lebret, Sask.

As the son of a road labourer in rural France, Joseph Hugonard had to tutor children of noble families in order to pay for his studies at the seminary in Grenoble. He served in a military hospital during the Franco-German War of 1870–71 and then, in fulfilment of a vow made to ensure his sick mother’s recovery, he entered the noviciate of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate at Notre-Dame-de-l’Osier to train as a missionary. Bishop Vital-Justin Grandin*, visiting from his diocese of St Albert (Sask.), ordained Hugonard on 28 Feb. 1874.

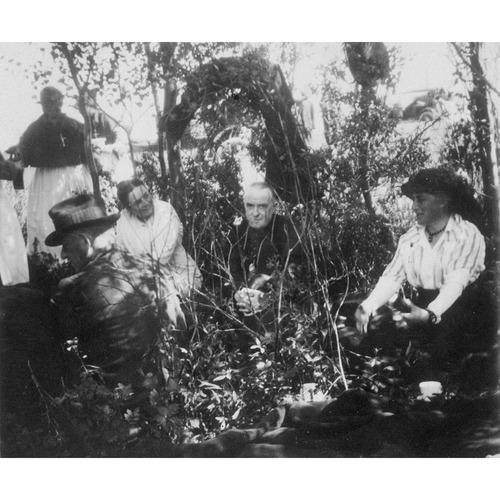

Assigned to work under Archbishop Alexandre-Antonin Tâché*, of St Boniface, Man., Hugonard arrived in Manitoba in the spring of 1874 and that summer travelled to the Qu’Appelle valley mission of St Florent, located in what is now Lebret. There Oblate missionary Jules Decorby directed his studies of the cultures of the Métis, Cree, Saulteaux, Assiniboin, and Sioux of the region. Hugonard went on bison hunts with the natives and met their chiefs, such as Sitting Bull [Ta-tanka I-yotank*]. He also started a boarding-school for native boys, in line with Oblate plans to evangelize young people and to teach them new ways of support to replace hunting as the bison died out. By 1879 he had become superintendent of the Oblate house at Qu’Appelle and had begun to preach to settlers in English.

In the early 1880s the federal government decided to establish industrial schools to fulfil treaty promises to native people as well as to provide for their future self-support. Negotiations with the Catholic hierarchy led to the opening of a school at Lebret in 1884, under Hugonard as principal. With the assistance of the Grey Nuns, a few Oblate fathers, and lay instructors, Hugonard was to make Qu’Appelle Industrial School a model Catholic educational facility for native people and the largest such institution in Canada. The native children, in parallel boys’ and girls’ schools, attended classes for half the day and engaged in domestic or agricultural pursuits the other half. English was the language of instruction; the girls played croquet and the boys cricket.

Yet Hugonard was sensitive to native culture. He taught the children their catechism in Cree and, since Cree was the first language of most of the children, he asked the sisters to teach new pupils first in Cree and then in English. In addition, he sought government funding for publication of a Cree-English primer. With respect to the government’s dictate that only “parents” could visit Indian schools, his awareness of the close familial ties among native people led him to interpret this word in the French sense of “relatives” rather than just the English sense of mother and father. He allowed a few white settlers’ children to attend as day scholars to help young Indians learn English, and Métis children were admitted on the same basis both as an assistance to their families and to boost school enrolment figures. Finally, he consulted with the Reverend Edward Francis Wilson about programs at Anglican schools for native children, and he cooperated with government agent William Morris Graham* in the development of an agricultural colony in the File Hills for ex-pupils of Qu’Appelle and neighbouring Protestant Indian schools.

Among Oblates, Hugonard’s efforts brought public praise but some private criticism: his achievements were considered too “secular” and too “personal.” Through the years 1884 to 1917 he had to adjust school programs to meet concerns of his congregation, the government, and the native peoples. In the 1880s government officials objected to his practice of hosting the families of students, partly for financial reasons and partly because the presence of native parents was thought to impede the process of assimilation. In the next decade the government not only imposed more regulations – English was henceforth to be the sole language of instruction – but also reduced the school’s funding. Meanwhile, smaller Oblate boarding-schools in the region competed with Qu’Appelle Industrial School for pupils.

Nor were these Hugonard’s only problems. Many native parents would not send their children to his school, and those who did became suspicious of school uniforms and marching drills after the military suppression of the North-West rebellion of 1885. They also objected to the emphasis on instruction in English and in trades and on conversion to Christianity. Hugonard was perturbed when chiefs such as Payipwat* made speeches in defence of native traditions while visiting the school, and he was even more worried by deaths of students at the institution since natives believed that residences where deaths had occurred should be abandoned. A hospital was built for the treatment of tubercular pupils, but Hugonard had difficulty explaining its purpose to native parents, just as he had difficulty explaining the Catholic belief that the deceased children were interceding in heaven for their families on earth.

The stress of his work at the school contributed to Hugonard’s private request that he be allowed to retire to the contemplative life of a monastery in France. A trip to Europe as a regional delegate to the Oblate general council of 1898 increased this desire, as did ongoing criticism within his congregation and native resistance to Catholic missions and schools. Then a visit to another western mission, Cross Lake, in 1903, and the destruction of Qu’Appelle Industrial School by fire in January 1904 drew Hugonard’s attention back to his life’s-work. In the midst of the controversy over French-language schools in the North-West Territories [see Sir Wilfrid Laurier], he succeeded in having the school rebuilt – a feat that silenced his congregational critics and strengthened his public contacts. He also pressed for government support and interdenominational cooperation in countering the involvement of ex-pupils in traditional native dances, especially the annual Sun Dance, which he saw as undercutting the Christianizing and educational work of government-funded mission schools.

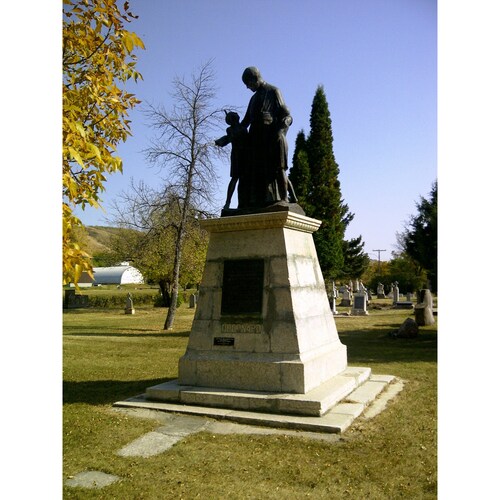

In 1913 Hugonard’s poor health – he suffered from Bright’s disease and lung problems – caused him to leave his school for medical treatment at a sanatorium near New York City. He was back in Saskatchewan within a few months, but he was hospitalized again at Regina in 1915. After convalescing for a couple of months in San Antonio, Tex., he returned once more to Lebret and resumed his work as principal. When he died there in 1917, natives as well as French and English Canadians came to his funeral. Later, natives and settlers of the Qu’Appelle valley erected a statue of him at the school.

Some scholars have remarked on the way in which government and missionary educational efforts for native peoples failed in their major aims of Christianizing and “civilizing” but unexpectedly fed native cultural persistence. Other scholars and even the Oblate congregation, in the wake of scandals concerning mid–20th-century Indian residential schools, have condemned such institutions as vehicles of imperialism. But few studies of specific schools have been undertaken, and those that have been done cast doubt on generalizations concerning the effects of the schools on native life; for example, it is clear that Hugonard’s school had a better record in promoting cultural continuity and family links than Father Albert Lacombe’s St Joseph’s Industrial School at Dunbow (Alta). In this regard, it is perhaps significant that the natives of the Qu’Appelle valley, in their 1984 commemoration of the industrial school’s centennial, celebrated its work as a contribution to their community’s history, part of a “century of learning.”

Joseph Hugonard compiled and published Cree hymns, with some most useful prayers ([Winnipeg, 1908]); a French edition was issued at Indian Head, Sask.

Most of the archival material relating to Hugonard is available at the Arch. Deschâtelets, Oblats de Marie-Immaculée, Ottawa, on microfilm or in the mass of transcripts and research notes collected by Gaston Carrière for his biography of the subject, L’apôtre des Prairies: Joseph Hugonnard, o.m.i., 1848–1917 (Montreal, 1967). The original documents are scattered among various Oblate archives in Canada; the Arch. Générales des Oblats de Marie-Immaculée, Rome; the Arch. de l’Archevêché de Saint-Boniface, Man., Fonds Taché; and the Arch. des Sœurs Grises, Montreal, Dossier Lebret.

NA, RG 10. La Liberté (Saint-Boniface), 21 févr. 1917, 9 mai 1922. Le Patriote de l’Ouest (Prince Albert, Sask.), 8 juin 1916, 1 mars 1917, 1 mars 1922. Qu’Appelle Progress (Qu’Appelle, later called Qu’Appelle Station [Qu’Appelle, Sask.]), 1885–22 Dec. 1898, continued as Progress, 29 Dec. 1898–1900. Qu’Appelle Vidette (Fort Qu’Appelle, [Sask.]), 9 Oct. 1884–27 Feb. 1896, continued as Vidette (Fort Qu’Appelle and Indian Head; Indian Head), 5 March 1896–99. Regina Leader, 1883–1905; 27 March 1916; 12 Feb., 3 March 1917. Can., Part., Sessional papers, 1873–80, reports of the deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs (in the reports of the Indian branch, 1872–73, and the Dept. of the Interior, 1874–79); 1880/81–1918, reports of the Dept. of Indian Affairs, 1880–1917. Robert Carney, “Residential schooling at Fort Chipewyan and Fort Resolution, 1874–1974,” in Western Oblate Studies 2: proceedings of the second symposium on the history of the Oblates in western and northern Canada . . . , ed. R.[-J.-A.] Huel with Guy Lacombe (Lewiston, N.Y., 1992), 115–38. Gaston Carrière, “The early efforts of the Oblate missionaries in western Canada,” Prairie Forum (Regina), 4 (1979): 1–25. Les Cloches de Saint-Boniface (Saint-Boniface), 4 (1905): 264–67; 8 (1909): 8, 116–19; 12 (1913); 43 (1944): 140–42. “Feu le R.P. Joseph Hugonard, o.m.i.,” Les Cloches de Saint-Boniface, 16 (1917): 67–70, 116–21. Jacqueline Gresko, “Everyday life at Qu’Appelle Industrial School,” in Western Oblate Studies 2, 71–94; “Qu’Appelle Industrial School; white ‘rites’ for the Indians of the old north-west” (ma thesis, Carleton Univ., Ottawa, 1970) [prepared by the author as J. J. Kennedy]. Dan Kennedy [Ochankugahe], Recollections of an Assiniboine chief, ed. and intro. J. R. Stevens (Toronto, 1972). D. G. Mandelbaum, The Plains Cree: an ethnographic, historical, and comparative study (Regina, 1979). J. R. Miller, “Owen Glendower, Hotspur, and Canadian Indian policy,” in Sweet promises: a reader on Indian-white relations in Canada, ed. J. R. Miller (Toronto, 1991), 323–52; Shingwauk’s vision: a history of native residential schools (Toronto, 1996); Skyscrapers hide the heavens: a history of Indian-white relations in Canada (Toronto, 1989). Missions de la Congrégation des missionnaires oblats de Marie Immaculée (Marseille, etc.), 1 (1862)–63 (1929). A.-G. Morice, History of the Catholic Church in western Canada from Lake Superior to the Pacific (1659–1895) (2v., Toronto, 1910), 2. Katherine Pettipas, “Severing the ties that bind”: government repression of indigenous religious ceremonies on the prairies (Winnipeg, 1994). E. B. Titley, “Dunbow Indian Industrial School: an Oblate experiment in education,” in Western Oblate Studies 2, 95–114; A narrow vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver, 1986). Irénée Tourigny, “Le père Joseph Hugonard, o.m.i.: son œuvre apostolique,” CCHA, Rapport, 16 (1948–49): 23–38.

Cite This Article

Jacqueline Gresko, “HUGONARD (Hugonnard), JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hugonard_joseph_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hugonard_joseph_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jacqueline Gresko |

| Title of Article: | HUGONARD (Hugonnard), JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 24, 2025 |