Source: Link

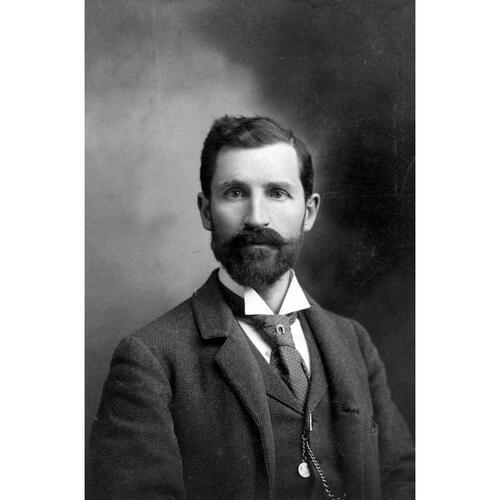

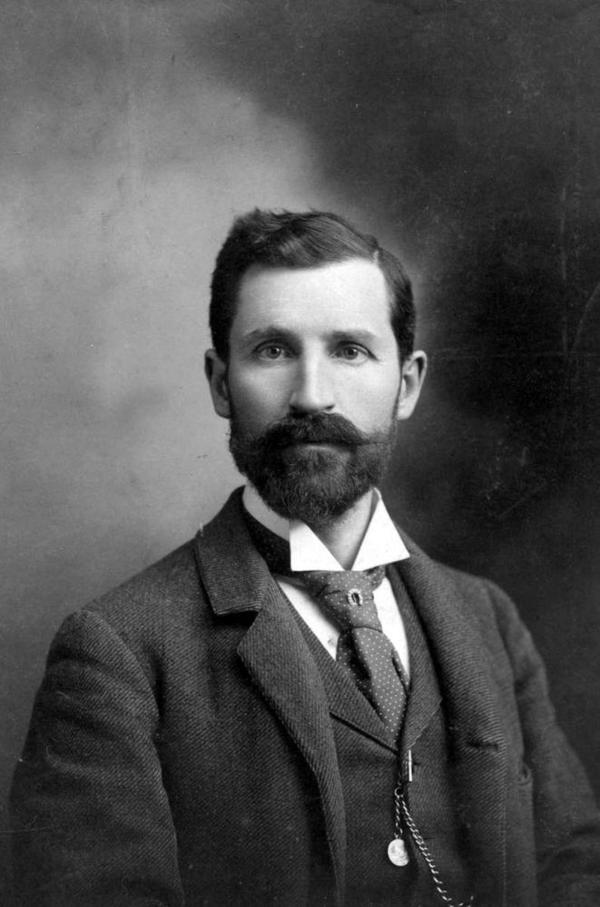

Gosnell, R. Edward, teacher, journalist, civil servant, librarian, statistician, author, and archivist; b. 14 Aug. 1859 in Saint-Dunstan-du-Lac-Beauport (Lac-Beauport), Lower Canada, son of John Gosnell (Gosnold, Gosneld) and Margaret Fachnie; m. 20 Oct. 1886 Agnes Theresa Wilson (d. 11 Dec. 1898) in Cobourg, Ont., and they had one daughter; d. 5 Aug. 1931 in Vancouver and was interred in Ocean View Burial Park in Burnaby, B.C.

Edward Gosnell was born in Lower Canada, third of the four sons of a Presbyterian Irish farmer and his Scottish wife. Educated in Ontario’s public-school system, by age 22 he had become a teacher. After about a year and a half he abandoned education for journalism and gained employment at the Chatham Tribune. He subsequently worked as an editor, first for the Port Hope Times for about two years and then at the Chatham Planet for five. By 1886 he had added the initial R. before his first name, which some sources claim stood for Richard or Robert, to avoid confusion with a namesake; he most frequently signed his published work R. E. Gosnell. While in Chatham, his involvement with the Macaulay Club, a debating and theatrical society, sparked his interest in historical research.

As Gosnell would tell it, he moved to Vancouver in 1888 to write for the Daily News-Advertiser, founded by Francis Lovett Carter-Cotton*. Yet an August 1894 Daily Colonist article summarizing his career up until then would note that he had also relocated “on account of ill health.” In early April 1890 he resigned as city editor of the Daily News-Advertiser and became a broker for a Vancouver real-estate firm.

By the end of 1890 Gosnell had left real estate for a job with the British Columbia Exhibit Committee, overseeing the development of an exhibit and escorting it to the Toronto Industrial Exhibition (later the Canadian National Exhibition) and other Canadian cities. In this role he wrote the first of his many publications about the province, a pamphlet extolling its virtues, entitled British Columbia: a digest of reliable information regarding its natural resources and industrial possibilities (Vancouver, 1890). Irate city taxpayers wrote letters to the Vancouver Daily World criticizing the pamphlet’s subsidization by the Canadian Pacific Railway and the municipal government, especially since it did not mention Vancouver. From Montreal, Gosnell responded to his critics in a letter published in the 23 Oct. 1890 edition of the paper: “Every man or family that can be induced to settle anywhere in British Columbia is a direct gain to Vancouver.” He blamed the pamphlet’s lack of information about the city on “the circumstances under which the printing was done.”

In the spring of 1891 Gosnell worked as the Canadian census commissioner for the district of New Westminster in British Columbia. He had Conservative political and social connections, and he was probably adept at promoting himself, factors that might explain his appointment in October 1893 by the minister of education as the province’s representative on the Dominion History Committee on Manuscripts, which was to award prizes for the best Canadian history textbook submitted by 1 Jan. 1895. He would be part of this group as late as 1913.

Gosnell achieved a measure of fame when the Conservative-affiliated premier Theodore Davie* named him the legislature’s first permanent librarian in November 1893. The post would be formalized through the Legislative Library and Bureau of Statistics Act, 1894. He was paid about $150 per month for his work as librarian and sometimes given additional funds to compile statistics. He also agreed to be the premier’s private secretary, although this post does not appear in the public accounts until about 1897, and he received no additional remuneration at that time. Through the statute Gosnell was empowered to acquire historical records. As early as June 1894 he was advertising in newspapers to solicit “reminiscences of pioneer settlement … old letters, journals, files of newspapers, books, pamphlets, reports, charts, maps, photographs, sketches and so on.” He amassed thousands of documents and apparently donated about a thousand items from his personal collection. The acquisitions would become the nucleus of the Provincial Archives and its Northwest History Collection. He also began gathering old documentation from government departments and Cary Castle [see George Hunter Cary*].

Gosnell’s ambitions were stifled, however, when he was abruptly dismissed in 1898 after the premiership had passed from the hands of Conservative-affiliated John Herbert Turner* to those of Conservative-affiliated Charles Augustus Semlin*. His librarian post was temporarily abolished and the money allocated was used to pay for Semlin’s choice of secretary. Ethelbert Olaf Stuart Scholefield took over Gosnell’s work at the Legislative Library, but as assistant and acting librarian at a salary of $55 per month. Not long after, Gosnell’s wife died and he was left to care for their young daughter, Helen Veronica. It might have been at this point that he took to drinking heavily, a habit that would become a problem.

In 1899 Gosnell did some political organizing for the fledgling provincial Conservative Party in the Boundary district and worked as the editor of the Greenwood Miner. He returned to government service the next year, however, when he was hired as secretary to Premier James Dunsmuir*, who also appointed him statistician in 1901. In the latter capacity his tasks included supplying information to potential investors and immigrants for a Vancouver Island colonization scheme that involved land owned by the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway.

Gosnell left his statistician post in 1904 to serve as editor of the Daily Colonist, a position he held for about two years. In 1906 he accompanied Conservative premier Richard McBride* to Ottawa and the next year to England for meetings at which it was hoped they would obtain better terms from confederation, an issue for which the provincial government would solicit Gosnell’s services, on and off, until 1916. He spent most of 1907 in England, where he attended the Federal Conference on Education, and was unable to be at his mother’s deathbed or funeral.

For the centennial of explorer Simon Fraser*’s 1808 descent to the mouth of the Fraser River, Gosnell convinced the government to officially hire him as provincial archivist from July 1908 to March 1909 (at a salary of about $160 per month) and finance a travelling exhibition. He mounted the Simon Fraser Centenary Exhibition, which showcased historical documents in honour of the province’s pioneers, and presented it in Victoria, Vancouver, and New Westminster. During his time as archivist he travelled to the interior and to Seattle, Wash., to acquire materials and also arranged to have documents from England copied. He had a talent for collecting, but none for archival organization.

Gosnell’s position was not renewed, and in July 1909 he was appointed secretary to the royal commission of inquiry on timber and forestry [see Frederick John Fulton]. Scholefield, who had been promoted chief librarian around 1900, succeeded him as the provincial archivist in 1910. (It was not until 1974 that the positions of legislative librarian and provincial archivist would be separated.) Gosnell continued to work for the British Columbia government on various contracts and was paid $300 per month in 1913–14 for his services regarding the continuing discussion about better post-confederation terms. In September 1914 Premier McBride appointed Gosnell his secretary. He served in the same capacity for Conservative premier William John Bowser in 1916 and, briefly, for Liberal premier Harlan Carey Brewster*, who let him know at the end of the fiscal year 1916–17 that his services were no longer required.

Gosnell used his knowledge to produce multiple works about the province and its history. The most significant was the Year book of British Columbia … (Victoria), which he edited, with provincial government assistance, between 1897 and 1914. A history o[f] British Columbia (n.p., 1906) is not the best example of his research and writing skills. A biography of Sir James Douglas*, a colonial governor, co-authored with Robert Hamilton Coats*, was published in 1908 in Toronto as Sir James Douglas, part of the Makers of Canada series; it might, since it was a collaboration, be his best work. In The story of confederation, with postscript on Quebec situation ([Victoria], 1918), he warns that the division created between English and French Canadians over conscription during the First World War and the calls for Canadian autonomy made by French Canadian nationalists [see Henri Bourassa*] are a significant threat to British imperialists such as himself, and that both languages should be taught in schools to foster national unity. While he made an undeniable contribution to the production of the province’s history, his work was characterized by both contemporary and modern critics as unorganized and sometimes inaccurate. As evidenced by his many letters published in various newspapers, he took an intense interest in many political issues affecting British Columbia – particularly those concerning federal–provincial relations such as immigration, Indigenous land titles, and the reconveyance, from Canada to the province, of the lands within the Railway Belt and the Peace River Block.

After losing his provincial government post in 1917, Gosnell moved to Ottawa, where he did some jobs for the federal government and reported from the Parliamentary Press Gallery. He made a bad housing investment, which led, he felt, to financial hardship. Between 1922 and 1929 Gosnell waged, from Ottawa, a letter-writing campaign asking Liberal premier John Oliver* and then Premier Simon Fraser Tolmie for compensation for his donation of books to the Legislative Library and a pension for his services to British Columbia. In Gosnell’s “Memorandum re statement of claim for superannuation,” which accompanied his 18 Dec. 1922 letter to Oliver, he noted: “The things in which I did seek to influence the Turner, Dunsmuir and [Edward Gawler] Prior governments were co-operative credit, cheap stumping powder, farmers institutes, small holding settlement, land clearing, co-operation with the Dominion in railway building, immigration, travelling libraries – with some success, too.” Gosnell also stressed that he had served as private secretary to premiers seven times, a fact Premier Oliver dismissed as irrelevant since the position was outside the civil service. In a memorandum dated 20 June 1925 Oliver concluded that his assessment of Gosnell’s situation three years earlier was correct: “Mr. Gosnell’s present impoverished condition is solely due to his own improvidence and his well known intemperance.”

By 1929 Gosnell had dropped his claim for compensation for his library donations; one of his successors as provincial librarian, John Hosie, could find no evidence that Gosnell had, in fact, made any. Following the election of Richard Bedford Bennett*’s Conservative government in July 1930, Gosnell declared in a letter to a cousin: “I have been voluntarily assured by a friend very close to Bennett and the Government that I shall be comfortably looked after for the rest of my life.” This scenario, however, never occurred. Because of his recurring bronchitis, Gosnell returned to British Columbia in April 1931 to live with his daughter. After his death the provincial government purchased a few documents and books for the cost of freight and granted $100 to help with funeral expenses. In addition to having a Canadian National Railways siding in British Columbia named after him in 1929, Gosnell was commemorated in 1950 when a portrait of him was unveiled by his daughter in the Legislative Library. The British Columbia public archives and library for which he built the foundations continue to attract researchers from around the world.

The publications of R. Edward Gosnell are indexed in LAC’s library catalogue.

AO, RG 80-5-0-144, no.[008468]. BCA, GR-0441.223, file 14; GR-0441.246, file 8; GR-0441.306, file P-3-D; GR-0975.2.8; GR-1738.61.16; GR-2951, no.1931-09-454793; MS-1111; PR-1407. FD, Church of Eng. (Valcartier, Que.), 18 Dec. 1859. LAC, R233-35-2, Ont., dist. Bothwell (178), subdist. Howard (A), div. 1: 27. Daily Colonist (Victoria), 26, 28 Aug. 1894; 21 Jan. 1950. Inland Sentinel (Kamloops, B.C.), 1 June 1894. Vancouver Daily Province, 15 April 1928. Vancouver Daily World, 15 April, 14 Aug. 1890. B.C., Treasury Dept., Public accounts (Victoria), 1893–1917. Terry Eastwood, “R. E. Gosnell, E. O. S. Scholefield and the founding of the Provincial Archives of British Columbia, 1894–1919,” BC Studies (Vancouver), no.54 (summer 1982): 38–62.

Cite This Article

David Mattison, “GOSNELL, R. EDWARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gosnell_r_edward_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gosnell_r_edward_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Mattison |

| Title of Article: | GOSNELL, R. EDWARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | April 25, 2025 |