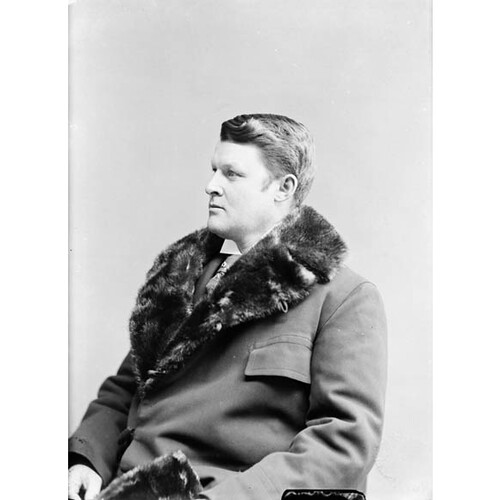

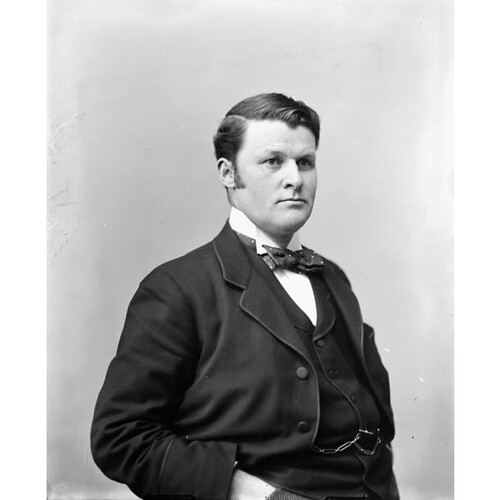

TUPPER, Sir CHARLES HIBBERT, lawyer, politician, and author; b. 3 Aug. 1855 in Amherst, N.S., second son of Charles Tupper* and Frances Amelia Morse; m. 9 Sept. 1879 Janet McDonald, daughter of James McDonald*, in Halifax, and they had four sons and three daughters; d. 30 March 1927 in Vancouver.

Charles H. Tupper was educated at King’s College in Windsor, N.S., and at McGill College, where he was governor general’s scholar. He took his law degree at Harvard University in 1876, was called to the bar of Nova Scotia two years later, and in 1881 joined the Halifax law firm of John Sparrow David Thompson* and Wallace Nesbit Graham*, a partnership that would include Robert Laird Borden* when Thompson went to the bench the following year. The son of the federal minister for railways and canals, Tupper was elected to the House of Commons for Pictou in 1882. Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* put him in charge of the Department of Marine and Fisheries in 1888, at 32 years of age the youngest Canadian cabinet minister up to that time.

He entered upon the administration of his department, where he would be ably assisted particularly by deputy minister William Smith*, with the utmost energy and seriousness. A dedicated conservationist, within a year he had offended two interest groups: the lumbermen over his enforcement of rules about sawdust in salmon rivers and east-coast fishermen, who objected to his insistence that lobsters taken be a minimum length of nine and a half inches. “Charly,” said Macdonald in a note to Thompson, now minister of justice, “has got the bumptiousness of his father, and should be kept in his place from the start.” Tupper would be all right, Thompson assured Macdonald: “He is of good metal, and is the best of his name.”

Tupper had a pronounced concern for the well-being of his riding, and that included patronage. Not for nothing was he re-elected in 1887, 1891, 1896, and 1900. Faced with his importunate letters, Macdonald had to remind him in 1889 of his proper responsibilities: “You have not yet been long enough a Minister to learn that every Cabinet Minister must subordinate his duties & his interests to & in his constituency to the general interest of the Dominion.”

In 1893 Tupper was named British agent, or research director, in the Bering Sea arbitration in Paris. He did so well that in September he was awarded a kcmg. After the death of Sir John Thompson in 1894, there was some talk of his becoming prime minister, which he was not above encouraging, but the fear then was “too much Tupper” – one in London (where his father was serving as high commissioner), another in Ottawa. So he became minister of justice in the government of Mackenzie Bowell*, though believing that Bowell was not really a fit person as prime minister.

Bowell’s inadequacy was abundantly confirmed in his mind early the following year. On 19 March the cabinet accepted Tupper’s report on the Manitoba school question as the basis of a remedial order and agreed that a dissolution should follow. Bowell disliked appealing to the people with the heather already ablaze, however, and he decided to postpone everything by having another session first. Tupper resigned, telling Bowell, “You cannot, I fear, keep Parliament together long enough to see the end of this fire.” No colleagues followed him. The rift was patched up on the strength of Bowell’s commitment to remedial legislation if Manitoba failed to restore Catholic rights. In this long story Tupper stands out firmly in support of what the law had decided, but around him on many sides were vacillation and weakness, not least in the prime minister. Bowell’s dithering created a more serious problem in January 1896, when Tupper again resigned, this time taking six of his colleagues with him. Some, but not Tupper, came back with the promise that Tupper Sr would become the next prime minister.

After the failure of the remedial bill in April and the dissolution of parliament, Tupper joined his father’s government as solicitor general. The administration was defeated in the general election that June, and in 1897 Tupper moved to the west coast to set up practice first in Victoria and then in Vancouver, though he continued to sit as mp for Pictou until 1904. He kept up his political interests until almost the end of his life, remaining in touch with leaders of the Conservative party both in Ottawa and in Vancouver. He objected, however, to some of the Conservatives in British Columbia politics, notably Sir Richard McBride*, premier from 1903 to 1915. His contacts in Nova Scotia were sufficiently important that Borden employed him on a speaking tour there in the federal election of 1911. Another federal politician with whom he was friendly was Richard Bedford Bennett*, elected mp for Calgary in 1911. They shared beliefs in the profligacy of the Borden government’s support of the Canadian Northern Railway and the McBride government’s even more reckless building of the Pacific Great Eastern from West Vancouver northward to Prince George. In the British Columbia election of 1916 Tupper in fact campaigned for Harlan Carey Brewster*’s Liberals against the Conservatives under McBride’s successor, William John Bowser*.

Tupper would frequently send Borden suggestions for appointments and policies that he wanted translated into action, and, being a Tupper, wanted fairly soon. Borden returned soft answers and no action. Tupper thought he was too much the same way with his cabinet. When in 1917 the minister of public works, Robert Rogers*, was accused of corrupt practice in his earlier role as minister of public works in Manitoba, Tupper was so annoyed by Borden’s pusillanimity in not dismissing Rogers forthwith that he actually wrote to the opposition leader, Sir Wilfrid Laurier*, to complain.

The 1914–18 war opened a chasm between Tupper and Borden that would never be bridged. What created the final break was Tupper’s bitterness at the death of his son Victor Gordon at Vimy Ridge in 1917. Tupper had three sons on the Western Front that year. The other had come back badly wounded in 1915. There were grievances with Borden about all three, but especially about Gordon, for support not given, for promotions not made: “General and Colonels . . . might, and did, ask for him as a Staff Officer. But – you know the rest. He had ‘no pull’. Had I been Prime Minister and you had worthy sons, I would have struggled to see that the chances were at least offered to them.” Tupper’s wife, Janet, begged him to suffer and not complain, but in a characteristic reflection he told Borden, “I am not equal to this, nor . . . do I consider it fair to you to conceal my feelings.” Tupper also disagreed with Canada’s signing the Treaty of Versailles separate from Britain, and he believed the implications of it dangerous. By 1920 his 40-year friendship with Borden was over.

In 1923, with the help of Major-General Alexander Duncan McRae*, Tupper formed a political party to run in the British Columbia election of the following year. He called it the Provincial party, to pull together Conservatives and Liberals “to save the province.” In British Columbia, he said, the name Liberal or Conservative was “but the borrowed plumage of men strutting before the electors.” The party took only three seats. Tupper continued to work at his law practice, which now included his son Reginald Hibbert. In his spare time he undertook to produce a book about his father, Supplement to the life and letters of the Rt. Hon. Sir Charles Tupper, bart., kcmg (Toronto, 1926). It was more hagiographical than its predecessor, and indeed was meant to be.

Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper had the Tupper courage, the Tupper eloquence, and the family concern for the glory of Tupperdom. He was energetic, talented, quick to seize a point, and almost as quick to take offence. He can be said to have been incorruptible, provided it be understood that with Tupper patronage was politics, not a form of corruption. That was the way political business was done in Canada, then and for a long time to come. Tupper contracted pneumonia in March 1927 and died on the 30th at his home in Vancouver. He was interred in Ocean View Burial Park, Burnaby.

[The major manuscript source is the Charles Hibbert Tupper papers at the Univ. of B.C. Library, Special Coll. and Univ. Arch. Div. (Vancouver), M644, a collection which is also available on microfilm at the NA. There is a rich lode of Tupper’s letters in the Sir John A. Macdonald papers (NA, MG 26, A), vols.286–87 and 529–30. Tupper letters are found as well in the Sir John S. D. Thompson papers (NA, MG 26, D) and the Sir Mackenzie Bowell papers (NA, MG 26, E). There is correspondence also in the Sir Charles Tupper papers (NA, MG 26, F). Obituaries are in the Ottawa Citizen, the Montreal Gazette, and the Vancouver Daily Province, 31 March 1927, and in Saturday Night (Toronto), 9 April 1927. An article on Tupper’s career appears in the Montreal Standard, 21 June 1924. A description of certain aspects of Tupper’s political life is in F. H. Patterson, “Some incidents in the life of Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll. (Halifax), 35 (1966): 127–62. The most important printed source is [I. M. Marjoribanks* Hamilton-Gordon, Marchioness of] Aberdeen [and Temair], The Canadian journal of Lady Aberdeen, 1893–1898, ed. J. T. Saywell (Toronto, 1960), with its richly rewarding introduction. Tupper’s close relations with Sir John Thompson are discussed in P. B. Waite, The man from Halifax: Sir John Thompson, prime minister (Toronto, 1985).

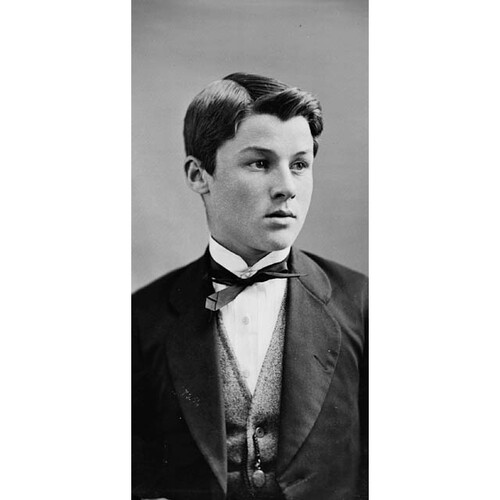

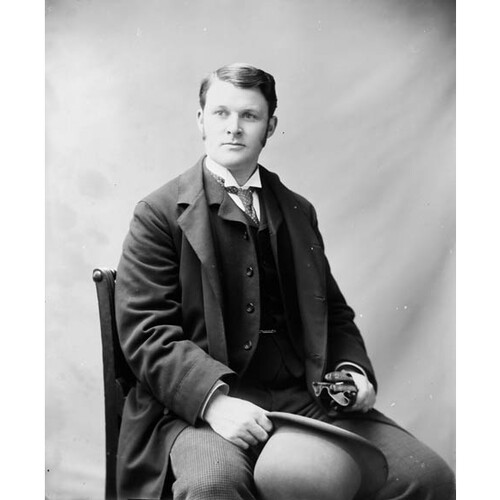

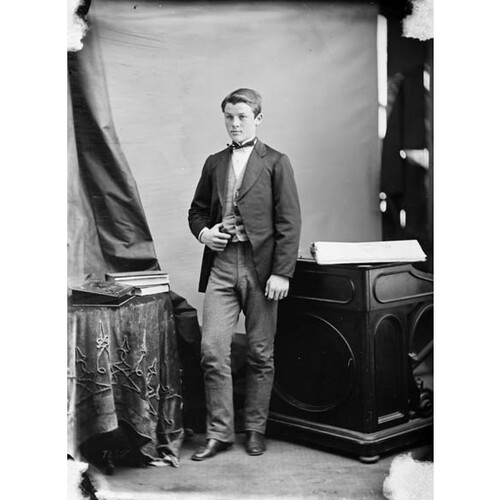

Of other secondary literature there is very little; from the beginning of the Canadian Periodical Index (Toronto) in 1920 to 1998, there is only one article, referring marginally to C. H. Tupper – J. A. Russell, “Tupperiana,” Atlantic Advocate (Fredericton), 53 (1962–63), no.12: 31–34 – and it comprises mostly pictures at that. But it does have an amiable photograph of Tupper aged 18 or 19, as well as one of his sister Emma. Tupper’s years in British Columbia are much less well known than his earlier career, but the C. H. Tupper papers give a substantial introduction to them. It is clear from these that the politics of the time exercised Tupper’s pugnacious mind, and that his literary activity often took the form of long and detailed letters to the editors of Vancouver and Victoria newspapers in defence of Tupperdom. p.b.w.]§

Cite This Article

P. B. Waite, “TUPPER, Sir CHARLES HIBBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 27, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tupper_charles_hibbert_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tupper_charles_hibbert_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | P. B. Waite |

| Title of Article: | TUPPER, Sir CHARLES HIBBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 27, 2025 |