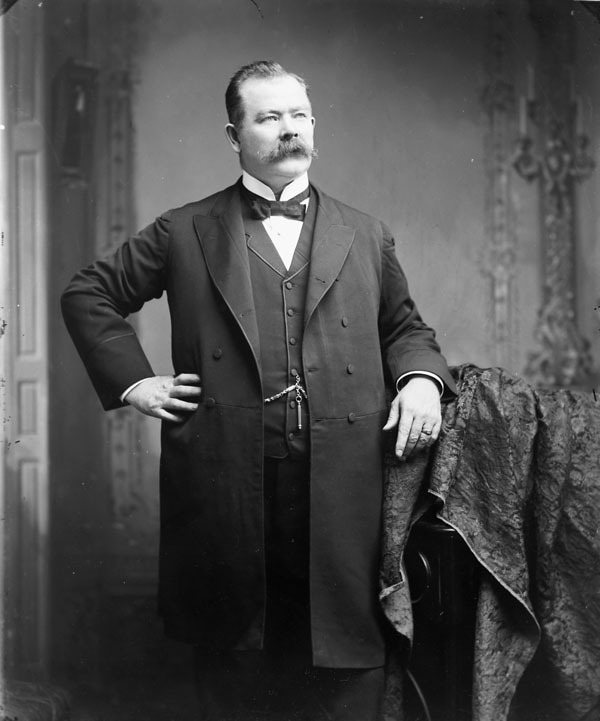

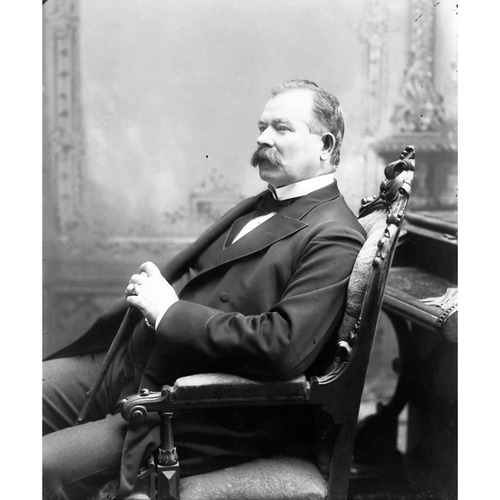

McLENNAN, RODERICK (R.), athlete, contractor, businessman, newspaper owner, militia officer, and politician; b. 1 Jan. 1842 in Glen Donald, Charlottenburgh Township, Upper Canada, third of the seven children of Roderick McLennan and Hannah MacDonald; d. unmarried 8 March 1907 in Cornwall, Ont.

Roderick McLennan’s grandfathers both came to Glengarry County, Upper Canada, from Scotland. His father was a farmer who served in the Glengarry militia during the rebellion of 1837–38. Roderick went to school in Glen Donald. He and his brothers, all big and agile, showed prowess in the strong-man events and foot-races at farmers’ picnics. Around the age of 17 Roderick performed the first of his athletic feats, leaping over three horses standing side by side. He then began throwing the hammer, at first using a cannon-ball attached to a handle, and he beat all local opponents.

From the early 1860s McLennan worked on railway construction in the Maritimes, Minnesota, and New York State, but he did not lose his interest in sports. At the queen’s birthday celebrations in Cornwall in 1865, he defeated the one-handed Scottish-games champion, Thomas Jarmy of Guelph, in two of three hammer-throwing contests, winning $1,000 in prize money. That summer he toured Caledonian games, then in their infancy, in the United States, Canada, and the Maritimes, competing for small prizes. He established several records in the hammer-throw: 216 feet with the 12-pound hammer in Cornwall, 285 feet with the 10-pound in Buffalo, N.Y., and 180 feet with the 16-pound at the international games in Charlottetown. The young McLennan was a popular draw and newspapers commented on his extraordinary strength and his gentility. Dubbed by some the Gentle Giant of Glengarry, he became commonly known as Big Rory. At about this time he took a second initial to distinguish himself from his father.

McLennan returned to competition at the Caledonian games in Toronto and Montreal in August 1870, in response to a challenge issued by Scotsman Donald Dinnie, the world champion of almost all Scottish games. The two men never met, however, because Dinnie refused to throw in anything but the old “Scotch” style, while McLennan was prepared to compete in both the old and the new style. In Toronto, McLennan, by then a powerfully built man standing six feet two inches and weighing 205 pounds, won the championship of America in the 18-pound heavy hammer, defeating his brothers Farquhar and Alexander R. Two years later, back in Toronto for the Caledonian games, McLennan competed against his three brothers, Farquhar, Alexander, and Angus R., in the shot-put and the hammer-throw, establishing world records for the latter event. Roderick’s exploits were listed in several record books and he was proclaimed world champion a number of times.

McLennan’s last throw was in 1877 at the queen’s birthday festivities in Cornwall, after a four-year absence from competition. At the end of the athletic program and as the day’s feature event, he made a powerful throw of the heavy iron ball. It hit Ellen Kavanagh, a young worker in a local textile mill, who had wandered onto the pitch, and she died instantly. Deeply overcome, McLennan never again threw the hammer.

From 1866 to 1870 McLennan had been engaged on railway and canal construction in Nova Scotia. For a time he lived in New Glasgow and there, in February 1866, he joined the Albion Lodge of freemasons. In 1870 he was employed on the Intercolonial Railway near Saint-Germain-de-Rimouski (Rimouski), Que., apparently as a construction foreman. Around 1870 he moved to Toronto, where he established himself as a contractor. From March 1872 into 1873 he was engaged by Francis Shanly* to build eight miles of the Georgian Bay extension of the Midland Railway.

McLennan then worked on the Canada Southern Railway before going west to superintend construction on the southern portion of the Pembina branch of the Canadian Pacific Railway, which opened in December 1878. From Winnipeg he moved in 1880 to Rat Portage (Kenora, Ont.), where he was briefly in partnership with William L. Baker, a local merchant, to supply goods for CPR contracts. McLennan himself contracted for several sections of the CPR in 1883–84 in the difficult terrain north of Lake Superior. In spite of lengthy disputes with the CPR over payment, these undertakings made him a wealthy man, assessed in 1885 as having a worth of $500,000. Indeed, during one suit against the CPR, when he was pleading insufficient resources to pay his employees and the expenses of extra work he had undertaken, his accountant was keeping secret cash accounts in order to disguise his real financial position. It may be, however, that these disputes and the CPR’s counter-allegations of fraud damaged his reputation as a contractor. Though McLennan bid for several contracts, he did no further railway work. One contract that he did secure, to build a section of the Winnipeg and Hudson’s Bay Railway, expired before any construction could be undertaken. His opponents later alleged that, when running for the Ontario legislature in 1886, McLennan had promised jobs on his contract to Glengarrians, even though he knew that none would materialize.

It may also be that McLennan lost interest in contracting as he was drawn to politics. In June 1882, during the federal election campaign, he visited Glengarry to speak in support of Donald Macmaster, the local mp and his solicitor and political mentor. When Macmaster was defeated in 1887, McLennan was asked by Sir John A. Macdonald* to protest the election of Liberal Patrick Purcell, another wealthy railway contractor. McLennan’s wealth and goodwill had attracted the attention of the prime minister, who repeatedly asked him to perform favours for the Conservatives. McLennan appears to have obliged with enthusiasm.

McLennan’s own electoral fortunes in the politically charged constituency of Glengarry were mixed. He failed to gain the provincial seat in 1883 and 1886. Following his first defeat he moved back to the region and established himself in a large house in Alexandria. From there he sought to secure the allegiance of electors by becoming their banker. In August 1885, with George Brown, previously manager of the Ontario Bank in Winnipeg, he founded McLennan and Brown, a private bank. Perhaps because of meagre returns, it was sold at McLennan’s insistence to the Union Bank of Canada in November 1886. McLennan none the less remained an active moneylender. He held promissory notes for several hundred farmers, in return for which, it is fairly evident, he expected their political support. From 1885 to 1891 he had out on loan an average of $57,986.21 per annum.

McLennan became president of the Glengarry Liberal-Conservative Association in 1885, thus solidifying his position in the party. He extended his base by acquiring an interest in several newspapers. Having bought the Cornwall Reporter and the Cornwall News, he merged them in April 1886 to form the Cornwall Standard. In December 1885 McLennan and Macmaster had transformed the Glengarry Review and Eastern Ontario Advertiser, a fledgling Liberal paper, into the Glengarrian, a Conservative paper. Though McLennan’s newspapers were to be important to his own and to his party’s fortunes in Glengarry, they would involve him in considerable controversy. In 1887, for example, the editor of the Glengarrian, C. J. Stillwell, was convicted of libel against Patrick Purcell.

By 1891 McLennan was well grounded politically and in the dominion election of that year in Glengarry he defeated Liberal candidate Jacob Thomas Schell, a lumber merchant from Alexandria. McLennan’s records indicate that he spent $11,869.49 on his campaign. In April, however, a petition was filed with the Ontario Court of Appeal contesting his return. He nevertheless took his seat in the House of Commons, where he gave his maiden speech on 17 July. When the petition case went before the Court of Appeal in October, McLennan’s testimony that he knew little or nothing of the organization and expenses of his campaign was unconvincing. The statements of one of his agents, who admitted to having treated electors, were more damaging and in December the election was ruled invalid. In the ensuing by-election, in January 1892, McLennan’s campaign was buoyed by visits from Ottawa of Sir Charles Tupper*, Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*, and George Eulas Foster*. Even though he was too ill to take an active part, McLennan triumphed over Archibald McArthur with an increased majority. His expenses are listed in his books at $4,702.99.

During the petition hearings, McLennan had run into difficulty with the president of the Glengarry Liberal-Conservative Association, John Alexander Macdonell* of Greenfield. Macdonell, a Catholic, was offended that McLennan had retained D’Alton McCarthy*, an outspoken mp as well as a lawyer, who had been critical of the party and had made attacks on Catholics and French Canadians over the language guarantees in the North-West Territories Act and over Quebec’s Jesuits’ Estates Act. He also worried about the reaction of party supporters in Glengarry, many of whom were French or Scots Catholics. The dispute eventually brought McLennan and Macdonell to court, when they filed suits against each other seeking payment for expenses in the hearings. Despite Sir John Thompson’s admonition of Macdonell, the quarrel did not abate. It dominated the Liberal-Conservative convention in Glengarry in 1894, when both men claimed credit for the idea of having a dominion reformatory located in the county, and would carry on into the election of 1900.

From 1894 McLennan faced another challenge, the rising popularity of the Patrons of Industry [see George Weston Wrigley]. The election that year of their candidate in Glengarry, David Murdoch Macpherson*, to the Ontario legislature portended electoral difficulty for McLennan and he became the Patrons’ most adamant opponent. In the 1896 federal election he conducted a ruthless campaign against Patron candidate James Lockie Wilson, who enjoyed the support of the Liberals. In an attempt to dislodge McLennan, they had agreed not to field a candidate. Not only did McLennan distribute damaging information about Wilson and the executive of the Patrons, but he used his newspapers to condemn them and pressured the Conservative Toronto Empire, in which he was an investor, not to print favourable accounts of Patron activities. His efforts were rewarded when he was returned by his largest majority, 734 votes.

In the commons the soft-spoken McLennan rarely entered debate, but he commanded respect for his acumen on matters relating to railway and public-works contracts. For a time, he rose in the party ranks. He was approached by Sir Mackenzie Bowell* to be minister of railways and canals, after most of Bowell’s cabinet resigned in January 1896, but he was not needed because nearly all of the dissenting ministers soon returned [see John Fisher Wood*]. As a backbencher, McLennan espoused several causes. Between 1891 and 1900 he introduced private member’s bills to protect the wages of workers on public-works contracts, to exclude non-Canadian contractors from such contracts, and to ensure that second-class railway tickets were made affordable for workers. In 1891 he took up in particular the matter of compensating the surviving militia veterans of the rebellions of 1837–38 and chaired a committee to examine the issue. His efforts earned the support of many in the house and of veterans in the United Counties of Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry, but no action was taken by either the dominion or the Ontario government. He spoke occasionally on agricultural issues and spearheaded an effort to protect the market for Canadian Cheddar cheese in Great Britain through more careful scrutiny and the branding of age and purity. Although most of his bills were non-partisan, he was at times an effective critic of the Liberal government of Wilfrid Laurier*, which came to power in 1896, and especially of its railway contracts, some of which, he argued, he could have undertaken for one-fifth of the price.

McLennan was by most accounts a good constituency man. His most important achievement was securing a promise from the government in 1894 to construct in Alexandria a reformatory to house 1,000 inmates. When construction was delayed, McLennan was accused of having obtained an idle promise, not unlike his own promise of jobs on the Hudson Bay railway years earlier. He felt betrayed and he castigated justice minister Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper* in September 1895, making clear that he would not be a candidate in the next election if progress was not made. Building began in May 1896, but after the election of the Liberals work was halted, and in 1897 the project was cancelled.

In 1900 McLennan again contested Glengarry, though for reasons of ill health he had to be pressed into doing so. He was defeated by J. T. Schell, who gained the votes of the French-speaking population. In an often bitter campaign, McLennan had been accused – maliciously and falsely, he countered – of being anti-French and anti-Catholic. In his political retirement he continued to assist the Liberal-Conservative party at election time.

McLennan does not appear to have had any clear political ideology. His ideas and actions were shaped by political and social circumstances in his riding. In Glengarry, the greatest achievement in some respects was simply getting elected and McLennan acquired a certain mastery in doing so. A careful campaigner, he was also an excellent candidate in such a heterogeneous riding. Not only was he a freemason and a Presbyterian, an asset among the Protestant electors, but his mother was a Catholic and he cultivated Catholic bishop Alexander Macdonell of Alexandria, with whom he was on good terms and from whom he often solicited advice. McLennan took pains to steer clear of the religious, linguistic, and racial controversies that divided the largely Scottish and French population of the united counties. He made some inroads with the French-speaking electors but could not retain their allegiance once Laurier had become prime minister. Unable to speak their language, he secured the services of francophones to discourse on his behalf at all political meetings, sending to Montreal or Hull for suitable orators. He was a significant benefactor in his county (he gave to French and English, Protestant and Catholic alike), and he endowed a fund to pay the way of a Glengarry native at Queen’s College, Kingston.

McLennan had varied business interests, many of which were shared with his coterie of Conservative friends and fellow members at the Albany Club (Toronto), the St James Club (Montreal), and the Rideau Club (Ottawa). He was a business partner of Hugh John Macdonald*, Sir John’s son, and he encouraged him to invest in such ventures as the Great Northern Gold Mining and Development Company of Rat Portage. In 1906 he organized the Peace River Coal and Coke Company, inducing Sir Charles Tupper, Sir C. H. Tupper, and several Cornwall businessmen to invest in its claims in British Columbia. A director of Manufacturers’ Life Insurance from 1888, the Toronto General Trusts Company, and the Atlantic and Lake Superior Railway, he was a significant investor in several Cornwall concerns, including the Eastern District Loan Company, of which he was president. He was a founding director and honorary president of the Farmers Bank of Canada, but took little part in its administration.

The bulk of McLennan’s investments were in mortgages on properties, farms, and churches in Glengarry ($141,557 in 1891) and in personal notes to area residents ($20,152 in 1891). In addition, he invested heavily in real estate, most of it in Glengarry and in the northwest, especially in towns along the CPR. He held large tracts of land in Rat Portage, Regina, and Winnipeg, and was a partner in the Glengarry Ranche Company in New Oxley (Alta), his interest in which he sold to Donald Mann*. At his death his property holdings were substantial: in Ontario they were valued at $74,141, in Manitoba at $166,815, and in Saskatchewan at $10,516.

The investment in which McLennan played the most active role was his newspapers. He exerted less control over the content of the Glengarrian than he did over the Cornwall Standard, but he had battles with the editors of both papers, usually over political concerns. In 1892, for example, the editor and part proprietor of the Glengarrian, A. E. Powter, complained to McLennan that his insistence on battering the Grits had led to a drop in advertising revenue, had forced the formation of a Liberal paper (the Glengarry News), and had failed to bring the promised printing contracts from the government. McLennan tried to sell the Standard several times in the 1890s. Having failed, he rejected subsequent offers to buy the paper and continued to own and play an active role in it. He wrote items on Ottawa politics, supplied its editor, W. G. Gibbens, with damaging information about his political opponents, and often directed him to refrain from commenting on sectarian disputes, French-language controversies, and the issue of separate schools. Despite their political benefit, McLennan’s papers were a financial burden, costing him significant sums over the course of his ownership.

McLennan’s chief preoccupation outside his political and financial interests was the militia, in whose annual camps he participated. He was gazetted a major in the 59th (Stormont and Glengarry) Battalion of Infantry in 1888 and was promoted lieutenant-colonel commanding in 1897; he resigned his command in 1900.

Rory McLennan was a wealthy man and he lived as one. From 1885 to 1891 he laid out $78,054 in house and personal expenses alone. He moved from Alexandria to Cornwall in 1899, settling in a grand house with a large formal garden. There he employed a coachman, a housekeeper, a private secretary, an accountant, and several lawyers to handle his real-estate investments and legal work. At election times he hired a stenographer to record his speeches, a political necessity in Glengarry, where his words were often used by Liberal newspapers to embarrass him. Both at home and in Ottawa he entertained political and other friends lavishly. He became stout in his later years and in the 1890s was often debilitated by diabetes and by Russian influenza. He sustained an injury to his foot in 1900, which later resulted in gangrene. In 1907, a week after an operation to remove part of his foot, he died at his home. In his estate he left $49,000 to his brothers and sisters, $66,500 to his nieces and nephews, and the bulk of his fortune, some $274,000, to his 11-year-old nephew Alexander Roderick McLennan, whom he had taken in some years before.

R. R. McLennan was typical of those who rose to prominence as railwaymen during the construction boom in Canada in the latter half of the 19th century. Helped no doubt by his reputation as a champion athlete and by his physical presence, Big Rory impressed employees and employers alike. His railway work not only made him very wealthy but put him in contact with men of influence, most of them fellow Conservatives, with whom he formed lifelong associations. McLennan gravitated towards politics and he stayed in it not because of the returns it promised, but because he enjoyed the prominence it accorded him. As a man from Glengarry, he retained strong links to his county and his people, and he returned there to act as their banker, their political representative, and, in many ways, their clan chief.

The Roderick R. and Farquhar D. McLennan papers at AO, F 238, which contain the personal and business papers of Roderick R. McLennan from 1883 to 1907, constitute one of the most complete records of any backbencher in the House of Commons during the late 19th century.

McLennan is the author of a pamphlet, To the surviving veterans of 1837–8–9 . . . the following brief statement of the efforts . . . made to obtain a suitable recognition of their services is respectfully dedicated (Alexandria, Ont., 1892).

AO, F 647, MU 2679–82; RG 22, ser.198, no.3026. NA, MG 26, F: 10140–41; MG 28, III 20, Van Horne letter-books, 6: 974; 14: 216; 19: 736 (copies). Cornwall Reporter (Cornwall, Ont.), 26 May, 2 June 1877. Cornwall Standard, 1886–1907. Empire (Toronto), 18 July 1891. Examiner (Charlottetown), 18, 28 Aug., 15 Sept. 1865. Freeholder (Cornwall), 1865–92. Gazette (Montreal), 12 Aug. 1872. Glengarrian (Alexandria), 1886–87, 1896. Globe, 1870–93. Halifax Citizen, 31 Aug. 1865. Montreal Herald, 1877–79. Ottawa Citizen, 26 May 1877. Ottawa Evening Journal, 4 Nov. 1892. Thunder Bay Sentinel (Prince Arthur’s Landing, later Port Arthur [Thunder Bay], Ont.), 1882–91. Toronto Daily Mail, 1872–81. World (Toronto), 10 March 1895. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 17 July 1891; 11 April 1894; 22 April, 12, 18 June 1895; 29–30 Jan. 1896; 8 April 1897; 12 April 1899. Canadian Sporting News (Toronto), 11 May 1895 (copy in AO, F 238). Canadian sportsman’s annual (Toronto), 1888. H. A. Fleming, Canada’s Arctic outlet: a history of the Hudson Bay Railway (Berkeley, Calif., 1957; repr. Westport, Conn., 1978), 22–27. [J. W.] G. MacEwan, The battle for the Bay (Saskatoon, 1975), 62–70. R. [C.] MacGillivray and Ewan Ross, A history of Glengarry (Belleville, Ont., 1979).

Cite This Article

Alexander Reford, “McLENNAN, RODERICK (R.),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mclennan_roderick_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mclennan_roderick_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alexander Reford |

| Title of Article: | McLENNAN, RODERICK (R.) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |