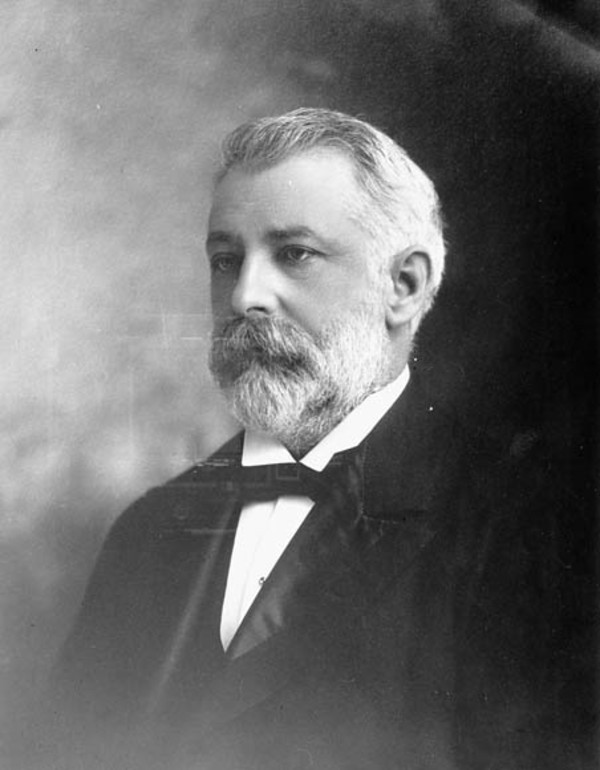

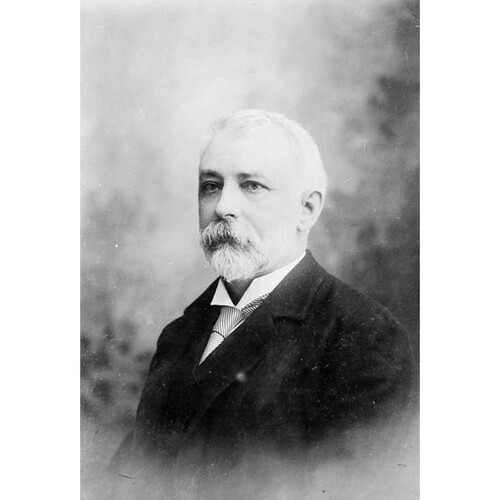

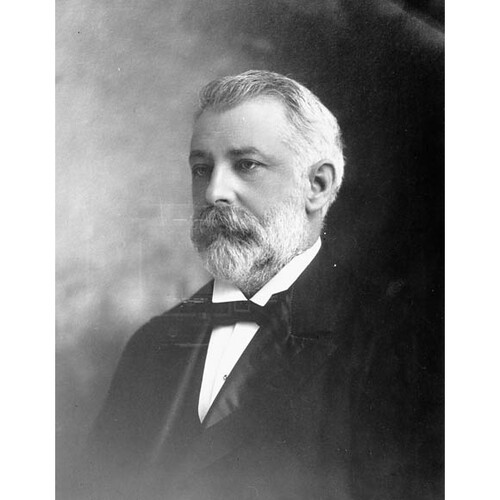

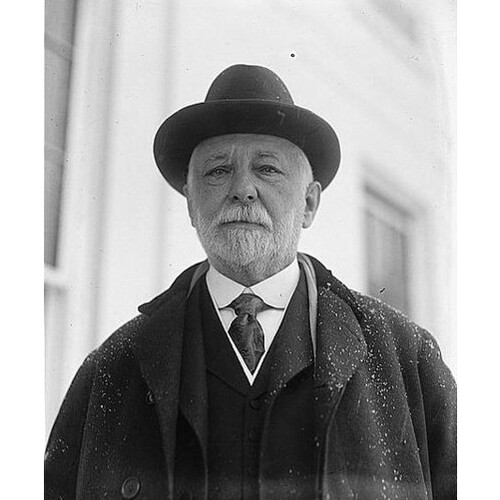

FIELDING, WILLIAM STEVENS, journalist and politician; b. 24 Nov. 1848 in Halifax, son of Charles Fielding and Sarah Ann Ellis; m. 7 Sept. 1876 Hester Rankine (d. 1928) in Saint John, and they had four daughters and one son; d. 23 June 1929 in Ottawa.

The son of a clerk of the market in Halifax, William Stevens Fielding was scarcely 11 years old when his mother died and he, his three brothers, and their sister were consigned to members of her family. William was placed in the care of his namesake, his uncle William Ellis, a Halifax grocer, with whom he lived until his marriage. Educated at the Royal Acadian School, the Halifax Grammar School, and the National School, William excelled in mathematics. Later he would attend courses at Dalhousie University on rhetoric and Shakespeare. At the age of 16 Fielding obtained employment with the Halifax Morning Chronicle, a Liberal journal founded and owned by William Annand*, but edited at this time by Jonathan McCully*. Fielding would remain with the paper for 20 years, working as a reporter, correspondent, and editorial writer and serving as managing editor from 1874 until 1884. For 14 years he was the Nova Scotian correspondent of the Toronto Globe, a journal whose editors and editorial policy he admired, an appreciation that the Globe reciprocated. On one occasion the Globe offered him a staff position but Fielding declined the offer, preferring to remain in Nova Scotia.

Fielding could scarcely have joined the Morning Chronicle at a more turbulent time for the journal and the province. McCully’s infatuation with confederation following the Charlottetown and Quebec conferences led to his dismissal as editor in early 1865. Both his replacements, Annand and Joseph Howe*, were firmly opposed to the Quebec resolutions. From his privileged vantage, Fielding worked closely with these legendary leaders of the anti-confederation movement and developed a lasting admiration for Howe and his cause. In 1869, after Howe and Archibald Woodbury McLelan* had secured better financial terms for Nova Scotia within confederation, Howe joined Sir John A. Macdonald*’s cabinet in Ottawa, a move that drove a wedge between him and Annand. Fielding skilfully steered a difficult course between his devotion to Howe and his loyalty to Annand, revealing a pragmatism and flexibility that was to mark his public career.

Fielding’s employment at the Morning Chronicle gave him unusual access to political power and influence. In the confusion that marked the restructuring of post-confederation Nova Scotian politics [see Philip Carteret Hill*], the Morning Chronicle was the command post for the province’s anti-confederation forces, and its editor became its most authoritative voice. As one of the paper’s highly partisan, diligent, and articulate journalists, Fielding continued to argue Nova Scotia’s cause against confederation and denounce Charles Tupper*’s treachery at the Quebec conference. He was a relentless critic of Macdonald’s Conservative government and, after 1878, the provincial Conservative administrations of Simon Hugh Holmes* and John Sparrow David Thompson*. An ardent defender of the old wind, wood, and sail economy, Fielding opposed the National Policy of 1879 [see Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley*]. He advocated economy in government, including the abolition of Nova Scotia’s Legislative Council. He was especially critical of the accounting practices of successive provincial governments, their calculation of uncollectable debts as assets, and their use of supplementary estimates for routine expenditures. Meanwhile, through his criticism and his continuing association with the Toronto Globe, Fielding drew ever closer to the federal Liberal party and its leader, Alexander Mackenzie*.

In this intensely partisan, engaged environment more active political involvement was almost inevitable. In 1879 Fielding helped found the Young Men’s Liberal Club in Halifax, and he participated more directly in the organization of the party. Although his lack of personal wealth had prevented him from accepting earlier invitations to run for public office, in June 1882 he contested the provincial constituency of Halifax County. Not only did he win the seat by a small majority, but his party formed the government. His disorganized colleagues (15 of the 24 successful Liberals were neophytes and the other 9 were divided on policy issues) asked Fielding, a novice himself, to assume the positions of premier and provincial secretary. When he declined, William Thomas Pipes*, another newcomer, was chosen premier. Later in 1882 Fielding relented and entered Pipes’s cabinet as a minister without portfolio. Organized, energetic, and meticulous, with a keen business sense, a skilful conciliator, an effective debater, a Halifax resident, and still editor of the Chronicle, Fielding soon gained influence, especially within his weak and divided party. Two years later, when party dissension and personal problems forced Pipes to resign, Fielding was the obvious but not unanimous choice to succeed him. Fielding accepted the positions of premier and provincial secretary, the second bringing with it the responsibilities of provincial treasurer.

Fielding’s principal obsession as premier was the province’s precarious finances, which he attributed to the unfavourable financial terms of its entry into confederation. Since 70 per cent of Nova Scotia’s revenue came from the dominion government, he first sought a more advantageous federal settlement. After a petition from the Nova Scotia legislature for better terms, a delegation to Ottawa, and correspondence with Macdonald and the new Liberal leader, an unsympathetic Edward Blake*, had all failed to elicit a favourable response, in 1885 Fielding supported a motion from the legislature calling upon Nova Scotia to consider withdrawing from confederation should the federal government fail to improve the province’s financial situation during its current session. Ottawa’s subsequent point-by-point rejection of Nova Scotia’s claims made an appeal to the people, a repeal election, inevitable.

In May 1886 Fielding moved a resolution asking Ottawa to release the province from confederation that passed the House of Assembly largely along party lines. In the subsequent provincial election Fielding made it clear that the federal government’s transportation and tariff policies and its failure to recognize Nova Scotia’s claims for better terms had left the province with no other option than secession. While his preference was for Maritime union, in the absence of strong support in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia was prepared to proceed alone. The electorate’s response appeared decisive: 29 Liberals, and 1 independent who favoured repeal, were returned as opposed to only 8 Conservative defenders of the union. Fulfilment of the secession mandate, however, was more difficult.

Fielding’s own views on secession were conveniently ambiguous. His party’s increasingly public divisions on the repeal issue (especially in Pictou and Cumberland counties and in Cape Breton, where the National Policy was promoting industrialization), as well as the British government’s opposition, persuaded the cautious premier to temporize, until he could induce the other Maritime provinces to join him or there was a change of government in Ottawa. He tried through both correspondence and personal visits to promote secession and Maritime union in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, but leading Liberals there remained timid. The Nova Scotia Liberals’ open split on the repeal issue during the federal election of February 1887, and the party’s failure to secure more than 7 of the province’s 21 federal seats, proved an irreparable political blow to secession.

Although strong anti-confederation sentiments lingered in Nova Scotia, Fielding’s position remained ambiguous. He continued to talk about Maritime union within or without Canada. Yet his active involvement in Honoré Mercier*’s interprovincial conference at Quebec City in October 1887 suggests a pragmatic willingness to seek redress within confederation, despite his initial insistence that his participation was without prejudice to Nova Scotia’s political future. Though he mentioned repeal during the provincial election campaign of 1890, in which his party won 28 seats, it was only to reiterate his view that the movement had been stalled by the federal results of 1887. In 1892, however, he refused to attend the Canadian high commissioner’s Dominion Day celebrations in London. On the other hand, his active role in Wilfrid Laurier*’s national Liberal convention in Ottawa in 1893 and his subsequent acceptance of an executive position in the Maritime Provinces Liberal Association confirm his willingness to give confederation a chance under Liberal auspices.

Meanwhile, Fielding sought internal means to solve or mask the province’s fiscal ills. His creation of a separate capital account that recorded only annual, not accumulated, deficits and his government’s voting of insufficient supplies helped to disguise the financial malaise. Securing more favourable interest rates against the province’s debt allowance, renegotiating debts, a fortuitous federal refund of provincial moneys that had been spent on certain public works, and the imposition of succession duties all provided some additional relief.

Fielding soon realized, however, that the province’s fiscal deficiencies would only be remedied through a more vigorous provincial industrial strategy, one that required a sharp reordering of his party’s industrial policy and political philosophy. Since coal royalties accounted for 17 per cent of the province’s public revenue, Fielding began his new strategy by extending royalties to slack coal. In 1892, conscious that coal was Nova Scotia’s most lucrative resource and aware of the coal industry’s capacity for further growth and its implications for public revenue, Fielding, through the mediation of Benjamin Franklin Pearson*, persuaded Henry Melville Whitney, a Boston entrepreneur, and his associates to invest in the Cape Breton coalmines. In return for a 99-year lease of the coalfields, the new company agreed to pay royalties of 12.5 cents per ton of coal, an arrangement that was confirmed by legislation early in 1893. By 1896 coal royalties accounted for 32 per cent of the provincial revenue, and they continued to rise. When reproached by the Conservative leader, Charles Hazlitt Cahan*, for the monopolistic nature and length of the lease, and the province’s reliance upon American capital, Fielding made clear that he was firmly committed to the industrialization of Nova Scotia and indifferent to the nationality of the capital and labour required to achieve this objective. The province’s and the provincial Liberals’ growing dependence upon the coal economy transformed the party’s political and ideological agenda, and influenced Fielding’s choice of George Henry Murray, who represented the industrial heartland of Cape Breton, as his successor in 1896.

Fielding was no less adept at cultivating the political support of labour. Soon after he became premier, he had forged an alliance with the nascent Provincial Workmen’s Association and a personal friendship with its influential general secretary, Robert Drummond. When Drummond failed to secure a seat in the House of Assembly in 1886 and again in 1890, Fielding named him to the Legislative Council. Meanwhile Fielding, at Drummond’s behest, introduced labour legislation that earned the premier an enviable reputation among miners: fortnightly wages, a minimum working age, mine inspectors, safety regulations, night schools, and compulsory arbitration before authorized lockouts. In Drummond’s view Fielding’s mining legislation was “the most advanced . . . in the world” and “set the pace even for Britain.” Fielding also knew how to placate apprehensive mine owners. When the general manager of the Acadia Coal Company in Stellarton, Henry Skeffington Poole*, objected to the province’s legislation requiring mine officials to hold certificates of competence, the premier, somewhat cynically, named Poole chairman of the provincial board of examiners. Fielding would continue to serve Nova Scotia’s coal and steel interests as Laurier’s minister of finance from 1896 until 1911.

Fielding’s transfer to federal politics was not entirely unexpected, since well before 1896 Laurier had identified him as a potential political ally and had worked assiduously to involve him on the national scene. While preparing for the Liberal convention in June 1893 Laurier invited Fielding to a small gathering of friends to plot strategy. He also named the provincial premier first vice-chairman of the convention and chairman of the central resolutions committee, which was responsible, among other things, for initiating a new Liberal policy on trade and tariffs. During the convention the party changed its old program of unrestricted reciprocity with the United States [see Sir James David Edgar*] for a program of tariff reduction and a more modest measure of reciprocity, in an effort to rid itself of the taint of disloyalty and to calm the fears of business. In its new platform it promised to establish a revenue tariff, reduced “to the needs of honest, economical and efficient government,” one that would promote freer trade, especially with Britain and the United States. Fielding played a large role in the drafting and adoption of the new policy.

As a founding member and vice-president of the Maritime Provinces Liberal Association, Fielding threw his full support behind Laurier in the election of 1896, though he cautiously refused to contest a seat until the Liberal victory in June assured him a cabinet position. Pressed by Laurier to become minister of finance, in August he won by acclamation the Nova Scotian constituency of Shelburne and Queens and took his place in Laurier’s talented first cabinet, among other experienced regional leaders such as Sir Oliver Mowat*, Andrew George Blair*, and Louis Henry Davies. Laurier’s choice of Fielding for the Department of Finance surprised many observers. And it angered Sir Richard John Cartwright*, the party’s long-serving finance critic and a former minister of finance. Free traders were apprehensive: some agreed with John Charlton* that Fielding was “too small a man for his position.” While Fielding’s appointment may well have been pressed upon Laurier by concerned businessmen such as George Hope Bertram*, anxious to block the access to office of the doctrinaire old free trader Cartwright, they appeared to lean on an open door. The prime minister seemed all too willing to secure a younger man, with less political baggage, and a proven friend of business interests, in the words of the journalist Paul Ernest Bilkey “a Free Trader by profession and a Protectionist in practice,” not unlike Laurier himself.

Gradually Fielding assumed the position of elder statesman in the Liberal party, second only to Laurier and increasingly seen as the heir apparent. Several things facilitated his ascendancy. A pragmatic, ambitious, tactful man of flexible political principles, he was a conscientious and able administrator, though inclined to procrastinate. He was also a man of blameless private and public morality, in striking contrast to some of his more high-spirited colleagues, two or three of whom Fielding felt deserved prison terms. Despite his lengthy political service he remained a relatively poor man; money did not stick to his hands. In the view of his political opponents he possessed, as Bilkey commented, “the not uncommon combination of personal rectitude and political dishonesty.” He was also a survivor; for quite apart from his personal virtues, by 1905 all the strong provincial leaders, those who had made Laurier’s first administration “the ministry of all the talents,” had left the cabinet. When Laurier failed to replace them with comparable men, except for Allen Bristol Aylesworth* and the youthful William Lyon Mackenzie King*, Fielding came to be regarded as Laurier’s right-hand man, and his logical successor.

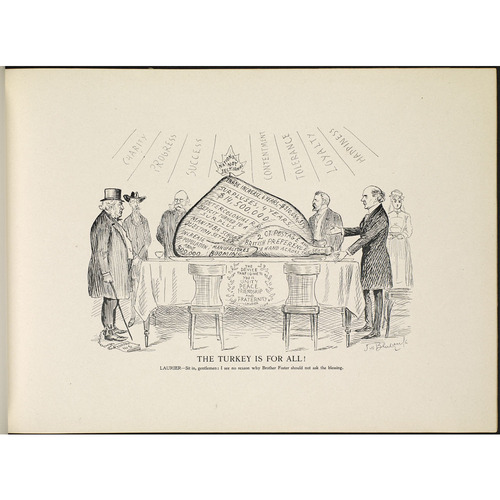

Moreover, as minister of finance, Fielding received credit for the rapid economic expansion that characterized the Laurier era, the “indubitable mascot and advance agent of good times,” as the Toronto Globe described him. During these halcyon days it would have been difficult to be a poor minister. The government derived over 70 per cent of its revenue from excise and custom duties on imports paid for by the vast sums of foreign capital that poured into Canada between the years 1901 and 1921, a situation that owed little to fiscal policy. After 1901 there was not much for a minister to do but watch the revenue increase, gloat over the government’s good fortune, and turn the situation to political advantage.

As minister of finance, Fielding endeavoured to develop external trade. In 1897, when efforts by John Charlton and others to negotiate more favourable American tariffs failed, Fielding revised the Canadian tariff in order to facilitate trade with Britain. Although the new tariff provisions applied to all countries that granted Canada similar terms, in essence the minimum tariff became an imperial preference; yet in 1902 Fielding cleverly helped frustrate Joseph Chamberlain’s efforts to create an imperial free trade zone. In 1907 Fielding introduced an intermediate tariff, between the general tariff and the preference, designed “as an instrument by which we may conduct negotiations . . . with any country which is willing to give Canada favourable conditions.” (It was also designed to bridge the gap between Canadian farmers and manufacturers whose diametrically opposed views on commercial policy had been aired before the tariff inquiry commission Fielding had established in 1905.) With this instrument in hand, in 1907 Fielding and Louis-Philippe Brodeur negotiated a trade treaty with France, and two years later Fielding obtained an agreement to promote trade with the British West Indies.

Although Fielding had made modest tariff adjustments in 1897, and again in 1907, the Conservatives’ National Policy remained essentially unchanged under the Liberals. The true father of the Fielding tariff, as his small concessions were named, was probably Joseph-Israël Tarte*, Laurier’s minister of public works and a former Bleu, who in 1897 intervened on behalf of Montreal business to prevent Fielding from introducing more substantial changes. While Fielding professed to see the tariff principally as a source of revenue, he appreciated its utility as an instrument of industrial development and was prepared to see it remain for a time. That time ended in 1910 when he and the minister of customs, William Paterson, negotiated a favourable reciprocity agreement with the United States, his most costly political blunder.

During his term of office Fielding took a number of other modest initiatives. He was responsible, for example, for the encouragement of Guglielmo Marconi’s experimentation with wireless telegraphy in 1901, the creation of a penny banking system in 1903, and the establishment of a branch of the Royal Mint in Ottawa in 1908. As acting minister of railways and canals in 1903, following the resignation of Andrew George Blair, he helped Laurier negotiate the agreement to construct the National Transcontinental Railway and signed the contract between the government and the Grand Trunk Pacific [see Charles Melville Hays*].

While many political analysts regarded Fielding as Laurier’s rightful successor, others felt that he could never become leader owing to his lack of support in Quebec. Until 1905 Fielding’s record on provincial rights and moderate tariff policy had won him a favourable reputation in Quebec; however, his support for Clifford Sifton’s opposition to the education guarantees in the Autonomy Bills of 1905 and for the Naval Service Bill of 1910, which provided for the establishment of a small Canadian navy, eroded that reputation. It was the Autonomy Bills, introduced into the house following Laurier’s triumphant 1904 re-election, that generated the most bitter feelings against Fielding in Quebec. In these draft bills, designed to provide a constitutional framework for the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta, Laurier had guaranteed the two provinces separate schools. Sifton, Laurier’s minister of the interior and “the Napoleon of the West,” refused to accept this provision and resigned from the cabinet in protest. Fielding supported Sifton, and threatened resignation. In the face of the opposition of his two most powerful colleagues, one from the east and the other from the west, Laurier was obliged to revamp the bills. French Canadian colleagues in the house resented Fielding’s strategic intervention in this controversy, partly owing to his reputed sensitivity to religious and linguistic issues in his own province. With Sifton out of the way, Fielding became Laurier’s undisputed second in command and his most obvious successor.

In fact, Fielding only narrowly avoided becoming prime minister in November 1908. At that time Laurier, discouraged by the results of the recent election, especially in English Canada, drafted a letter of resignation requesting Governor General Lord Grey* to call upon Fielding to form a government. But Fielding, conscious of continuing French Canadian resentment owing to his role in revising the Autonomy Bills, persuaded Laurier to delay resignation until 1910, after which Fielding would become leader for two sessions and then call an election. The defeat of the Liberal candidate by his Nationaliste opponent in the famous Drummond and Arthabaska by-election of 1910, however, prevented a transfer of power that year and the party’s collapse in the general election of 1911 altered the question of succession.

The most prominent issue in this election was the reciprocity agreement with the United States that Fielding had announced so triumphantly in the House of Commons in January 1911. The impetus to improve commercial relations between the two countries had come the previous year from the United States and, for Laurier’s government, had coincided with increasing political pressure from farmers for tariff reform [see James Speakman*]. The principal feature of the agreement was the free exchange of natural products and a small number of manufactured goods. The issue, however, backfired. In February, 18 prominent Liberal businessmen in Toronto issued a manifesto protesting the arrangement [see Sir Byron Edmund Walker]. Confident of the popularity of the reciprocity agreement, Laurier accepted the Conservative party’s challenge to call an election for 21 September. Disorganized, ill prepared, and carrying 15 years of political baggage, the ageing Liberal party was defeated. Fielding was among the casualties.

After the election Fielding’s chances of replacing Laurier receded. Laurier’s own popularity began to rebound, especially in Quebec among disillusioned Nationalistes, notably Henri Bourassa*, the influential proprietor of Le Devoir. Sensitive to changing public sentiments, Laurier began to take his distance from his party’s rejected trade and naval policy and to focus on the high cost of living. In contrast, Fielding’s stubborn commitment to the Liberals’ defunct program, made clear in interviews and speeches during his visit to England in 1913, not only offended party members but reinforced the notion that he was chiefly responsible for the party’s 1911 electoral defeat. Increasingly, Fielding appeared old and inflexible, and Laurier himself began to consider younger successors, among them W. L. M. King. Although in 1912 Robert Bickerdike, the Liberal mp for the Montreal constituency of St Lawrence, had offered to relinquish his seat in favour of Fielding, the party did nothing to redeem Bickerdike’s offer, a failure that suggests Fielding’s fading political reputation.

This became painfully clear in 1913, soon after Fielding moved to Montreal to resume his career in journalism. His friends planned a large, welcoming banquet, and many speculated that Laurier would use the occasion to announce his own retirement and name Fielding as his successor. Consequently over 200 Liberals, including prominent Liberals from other provinces, gathered to participate in the event. Although the hour was past midnight when Laurier rose to speak, the former prime minister gave a fighting oration that aroused the awe and admiration of his audience, and that contrasted sharply with Fielding’s own lacklustre performance. During this speech Laurier announced the new Liberal policy and made it clear that he had no intention of relinquishing the crown. Many party followers were elated. Others were astonished at Fielding’s “humiliation.” To Henri Bourassa the reason was clear: physically and mentally Fielding was a man of the past, more at home “in the world of the archaeologists and the kingdom of the Seven Sleepers.”

Fielding’s return to journalism appeared no more successful. He had moved to Montreal in December 1912 to assume the editorship of the Daily Witness. The paper was acquired some months later by the Telegraph Publishing Company Limited, of which Fielding was president, and renamed the Daily Telegraph and Daily Witness, but it soon encountered financial difficulties. In January 1914 it was purchased by Sir Hugh Graham*, proprietor of the Montreal Daily Herald, who merged the two papers. The attempts of Graham, a strong-willed Conservative, to dictate editorial policy led to a “first class blow out.” Fielding left the Montreal Herald and Daily Telegraph that year and, with James John Harpell and Jack C. Ross, acquired the Journal of Commerce, a weekly that he converted into a daily. Fielding served as both editor of the paper and president of the publishing company. This small publication reverted to a weekly in 1915, then became a monthly, and later moved to Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue. Fielding continued to edit the Journal of Commerce until he joined W. L. M. King’s cabinet in 1921.

While Fielding’s Montreal sojourn may have restored his links with the city’s business community, World War I further soured his relationship with French Canada. The problem was his support for conscription and his perceived betrayal of Laurier. Throughout the conscription crisis, Fielding consistently sought a middle way where there was no middle way, perhaps cynically seeking political advantage. In the spring of 1917 he drafted a letter, which he never published, justifying Laurier’s refusal to join a coalition government. In it he pleaded with his intended readership for an understanding of French Canada’s opposition to compulsory military conscription and called for a referendum to decide the issue. But when western Canadian Liberals began making their peace with Sir Robert Laird Borden*’s Conservatives, Fielding (aware that Laurier was contemplating resignation from the party’s leadership) publicly endorsed the formation of a national government, while withholding his approval of Borden’s proposed terms for it. In October, when support for Borden’s Union government grew among western and Ontario Liberals, Fielding again revised his position and sought to persuade Nova Scotia Liberals to join the Union movement to avoid being isolated. Although he refused a Unionist cabinet post, Fielding endorsed the decision of Alexander Kenneth Maclean*, another Nova Scotian Liberal, to enter Borden’s government, gave Borden his full support, and in the election in December was returned unopposed as a Unionist in Shelburne and Queens. He insisted upon sitting on the cross-benches, however, thereby offending many Liberal Unionists.

Fielding might easily have accommodated himself to Laurier’s generous criteria for individuals to retain caucus membership: oppose conscription and the Union government; support conscription but oppose the Union government; or run as independent Liberals. But he chose to follow the majority of his party, hoping, perhaps, to play peacemaker and power-broker once the war ended. Whatever popularity his vacillating strategy may have gained him in the rest of Canada, it won him no favour in his native province or in Quebec. In Nova Scotia, despite the efforts of Borden, Fielding, and Premier George H. Murray, Unionist electoral manipulation, and the sobering effects of the great Halifax explosion only 11 days before the election, the Laurier Liberals obtained 45.5 per cent of the popular vote. Moreover, Nova Scotian Liberals, like their Quebec colleagues, would not forgive Fielding his desertion of the old chief, as they made clear during the Liberals’ leadership convention in August 1919.

Nevertheless, Fielding made a remarkably strong showing at this gathering. Laurier had called for a national convention immediately after the war, to reunite the party and give it a post-war policy direction. Upon his death in February 1919, the convention became a six-person leadership contest. Although King and Fielding protested their lack of interest in the position, they were the principal contenders and they offered Liberals a stark generational and ideological choice. Fielding’s hesitations in seeking the leadership were based on his fear that Laurier loyalists in Nova Scotia and Quebec would spoil his chances, and his strong opposition to the radical platform that had been adopted by the convention in its first two days. When at last he agreed to stand, he threatened, should he be chosen leader, to have his leadership ratified by the parliamentary caucus on the condition that he would not be bound by the program. Opposition to Fielding came from various corners, “quite the fiercest” from his former cabinet colleagues Sydney Arthur Fisher, Sir Allen Aylesworth, Frank Oliver*, and George Perry Graham*, some seeing him as the tool of Montreal’s St James Street businessmen. Fielding’s greatest support came from the conservative members of his party, such as George H. Murray, Sir Lomer Gouin, Louis-Alexandre Taschereau*, John Oliver, William Melville Martin*, and Walter Edward Foster*, from Montreal business interests, and from those who felt his candidacy was essential to the party’s unity. With their support he pushed the convention to a third ballot, which King won by only 38 votes. According to Adam Kirk Cameron, a close friend and confidant of Laurier and a Fielding supporter, Fielding obtained a “very heavy vote from Ontario and the West . . . and a surprisingly large vote from the province of Quebec, notwithstanding the Autonomy Bills and his attitude toward conscription.” But in Cameron’s view Fielding “was defeated for leadership of the Liberal party by the people of Nova Scotia,” whose delegates had cast over half of the 38 votes separating the two candidates against Fielding. They had also run Daniel Duncan McKenzie, the interim party leader and a Nova Scotian, to prevent Nova Scotia votes going to Fielding. During the course of the ballot Lady Laurier asked Cameron to inform the convention that Fielding was her late husband’s choice for leader. Anxious to restore party unity, Laurier, it appears, had concluded that Fielding would be best placed to heal the party’s wounds.

Disappointed by the outcome and unhappy with the party’s radical program, Fielding threatened to sit as an independent Liberal. Although friends persuaded him to join the front benches, he continued to remind the house that he had never accepted the party’s platform. During the 1921 federal election, however, he gave the party his full support, and was re-elected in Shelburne and Queens. By projecting an image of unity, his endorsement of the new leader may well have had “a deciding influence” in Ontario and the Maritime provinces. Fielding’s strength at the Liberal convention and his continuing popularity among the more conservative wing of the party prevented King from ignoring him. When the Liberals were returned to power in December 1921, he took up his old post as minister of finance. Although he retained the position until 1925, he remained something of an anachronism, heard but not heeded by the new leader. From late 1923 he was too ill to fulfil his duties, which were assumed by an acting minister, James Alexander Robb.

The little grey man, who had in the past too frequently chosen the path of silence and compliance, in his old age refused to make concessions to the new era. He disapproved of Canada seeking a separate representation at the Paris Peace Conference, and deplored the country’s new obsession with status. He also opposed the idea of Canada obtaining representation in Washington and signing its own treaties. Although he feared that the country was “right at the very verge of independence,” he wrote a six-stanza version of “O Canada,” and designed a new Canadian flag, since he regarded the Red Ensign inappropriate because it was a sea flag and “more suggestive of the red flag of the communists than of anything Canadian.” His world remained the world of pre-war Canada.

A friend of business, despite his free-trade antecedents, Fielding served on the boards of a number of companies, including the Scottish and Dominion Trust Company, of which he was chair. He was vice-president of the Nova Scotia branch of the Canadian Red Cross Society, a governor of Dalhousie University, an engaged member of his Baptist church, and an active clubman in Halifax, Ottawa, and Quebec City. Although he was presented at court on several occasions, he resisted titles for himself. Acadia, McGill, Queen’s, Dalhousie, and McMaster universities bestowed honorary degrees and he was made an imperial privy councillor in 1923. His portrait was painted by John Wycliffe Lowes Forster*.

An individual of apparent contradictions, secretive, cautious, and a procrastinator, Fielding was a man of personal probity though, opponents would add, of political deviousness. His friends and supporters saw him as an honest, conscientious, disinterested public servant, a great parliamentarian, tactful, without airs, “one of the brightest intellects Canada has yet produced,” and “the greatest Finance Minister Canada has ever possessed.” In 1910 his friends “of all shades of political opinion” created a trust fund of $120,000 for him and when he retired in 1925 parliament voted an annuity to its longest serving minister of finance. He died four years later, predeceased by his wife and one of his daughters, and he was buried beside them in Beechwood Cemetery in Ottawa.

LAC, MG 26, G; MG 30, E70. National Library of Scotland (Edinburgh), mss 12446-587 (4th Earl of Minto, corr. and papers). NSARM, MG 2, 63-223, 422-541, 784-90(B). Univ. of Toronto Library, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, ms coll. 110 (John Charlton papers). P. [E.] Bilkey, Persons, papers and things: being the casual recollections of a journalist, with some flounderings in philosophy (Toronto, 1940). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1896-1911; 1922-23. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.3. Robert Drummond, Minerals and mining, Nova Scotia (Stellarton, N.S., 1918). [C.] B. Fergusson, Hon. W. S. Fielding (2v., Windsor, N.S., 1970-71). D. J. Hall, Clifford Sifton (2v., Vancouver and London, 1981-85). D. C. Harvey, “Fielding’s call to Ottawa,” Dalhousie Rev. (Halifax), 28 (1948-49): 369-85. C. D. Howell, “W. S. Fielding and the repeal elections of 1886 and 1887 in Nova Scotia,” Acadiensis (Fredericton), 8 (1978-79), no.2: 28-46. Donna McDonald, Lord Strathcona: a biography of Donald Alexander Smith (Toronto and Oxford, 1996). K. M. McLaughlin, “W. S. Fielding and the Liberal party in Nova Scotia, 1891-1896,” Acadiensis, 3 (1973-74), no.2: 65-79. N.S., House of Assembly, Debates and proc. (Halifax), 1882-96. Benjamin Russell, “Recollections of W. S. Fielding,” Dalhousie Rev., 9 (1929-30): 326-40. O. D. Skelton, Life and letters of Sir Wilfrid Laurier (2v., Toronto, 1921).

Cite This Article

Carman Miller, “FIELDING, WILLIAM STEVENS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fielding_william_stevens_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fielding_william_stevens_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carman Miller |

| Title of Article: | FIELDING, WILLIAM STEVENS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |