As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

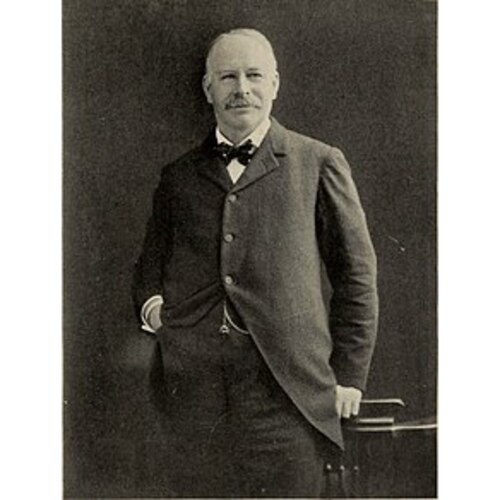

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

WHITNEY, HENRY MELVILLE, entrepreneur; b. 22 Oct. 1839 in Conway, Mass., second of the seven children of James Scollay Whitney and Laurinda (Lucinda) Collins; m. 3 Oct. 1878 Margaret Foster Green in Brookline, Mass., and they had four daughters and one son; d. there 25 Jan. 1923.

Henry Whitney grew up in comfortable circumstances in Conway. He and his brother William Collins (who would become secretary of the navy in Stephen Grover Cleveland’s first administration) graduated from Williston Seminary in Easthampton, Mass., in 1859. For the next seven years Henry held a variety of clerical positions, played the cotton market, and concocted schemes to raise sunken vessels during the Civil War; he could now exchange stories about unsuccessful speculations with his father and brother. In 1866 he went to Boston as agent for his father’s thriving Metropolitan Steamship Company and he became president of the concern after his father died in 1878. In 1886 he formed the West End Land Company, became over-extended, and linked the firm with the equally new West End Street Railway Company to promote his land development scheme. Whitney absorbed five other street railway systems around Boston and both West End companies proved profitable. The pattern of mergers, corporate linkages, and speculative ventures was established. He began to experiment with electric cars in 1888 to replace the street railway company’s 10,000 horses. Frederick Stark Pearson* joined him in 1889 as chief engineer of this firm.

Earlier in 1889 F. S. Pearson had linked up with Benjamin Franklin Pearson*, a promoter of the People’s Heat and Light Company Limited in Halifax, which intended to use coal to produce fuel gas for heating and lighting. F. S. Pearson and Whitney were also interested in Nova Scotian coal as a possible source of fuel for Whitney’s New England projects. Their group would soon be known in provincial circles as the “Syndicate.” One coalmine was quickly purchased and options were obtained on others in the coalfield south of Sydney harbour. Premier William Stevens Fielding was quite receptive to the idea of combining competing Cape Breton mines in an expanding Nova Scotia coal industry and the group was offered an unprecedented 99-year lease at a fixed royalty. Whitney was particularly attractive to the Liberals because his steamships and street railway generators were large consumers of coal. The Syndicate exercised its options, picking up most of the existing collieries in east Cape Breton, along with local players such as John Stewart McLennan* and David MacKeen*.

The Dominion Coal Company Limited was incorporated on 1 Feb. 1893 with Whitney as president, F. S. Pearson as engineer-in-chief, and B. F. Pearson as secretary. Numerous efficiencies and improvements were quickly evident, and within a decade Dominion Coal had 4,000 employees and production had quadrupled. There was also a long list of expensive mistakes and extravagant expenditures. Control was weak, and many of those involved knew nothing about coalmining. Dominion Coal’s establishment was accompanied by the issue of a large amount of promotional stock, which took a tumble when Whitney failed to get the American duty on coal eliminated. Speculators had a field day. While B. F. Pearson tried unsuccessfully to drum up markets for coal in, among other places, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, ventures centring on the use of coke in the United States proved more fruitful and a new plan began to take shape. This project, which contemporary observers immediately linked to Dominion Coal when Whitney first announced it in January 1896, was the Massachusetts Pipe Line Gas Company. The company was to purchase gas from the New England Gas and Coke Company, also controlled by Whitney, which in turn would be supplied by Dominion Coal. On 30 Sept. 1897 a contract was signed between New England Gas and Dominion Coal and, despite the American duty, within a couple of years a new plant at Everett, Mass., began to consume large amounts of coal. Unfortunately, this arrangement meant a large missed market at higher prices which almost ruined Dominion Coal and led to the conclusion that the contract had been part of a scheme to enhance the stock value of Whitney’s New England gas companies.

Concessions from local government in Cape Breton and the provincial Liberals under Premier George Henry Murray, as well as the promise of federal bounties, smoothed the way in June 1899 for the organization of the Dominion Iron and Steel Company Limited, which had been incorporated the previous March. According to Whitney, Sydney offered more advantages for steel making than anywhere else in the world, and the international competition was initially concerned. Whitney became president of the new company and six of his business friends, who had also been on the original Dominion Coal board, joined him as directors. More than the faces were familiar. Reckless and extravagant expenditures, miscalculations, and lack of control, due partly to inexperience, meant that one-third of the initial outlay for construction was wasted. This incompetence left a legacy of high costs, allowing the plant to be profitable only during periods of high prices. A contract between the coal and steel companies brought grief to both. In 1901 it was estimated that 90 per cent of Dominion Coal’s production was locked into low-price contracts. The steel company’s stock became the sport of speculators. Miners and steelworkers carried their share of the burden through low wages. Halifax had had direct experience of this approach as well. People’s Heat and Light, which had been chartered in 1893, featured Whitney as president and B. F. Pearson as secretary. Even though People’s had the advantage of low-cost coal, its substandard materials, stock market speculations, and limited experience in industrial development ensured that the company, in the words of Kyle Jolliffe, “collapsed under the heavy weight of its own debts” in less than a decade.

The coal and steel industry that Whitney promoted would employ many thousands throughout the 20th century and left an indelible mark on Cape Breton Island. Although he and his business friends did not have a monopoly on mismanagement, or on dissatisfaction with operating profits, they helped to ensure that the early years of the modern industry in Cape Breton would be difficult ones. The continuing problems led to his early withdrawal from the region; his controlling interest in the coal and steel companies passed to a group headed by Montreal financier James Ross* in 1901. He resigned from the Dominion Coal board in December 1903 and although he continued to be linked with smaller concerns in Cape Breton and remained on the steel board until 1909, his focus was redirected to New England. He was elected president of the Boston Chamber of Commerce in 1904 and made two unsuccessful runs for state office in the next few years, promoting tariff reform and reciprocal trade relations between Canada and the United States.

Whitney was a promoter and a dreamer, with a penchant for mergers and corporate connections. While he may have been, at 10, “a close lad in financial matters,” as one account of his early life noted, by 25 he confessed he had disgusted himself with his splendid schemes on paper which proved worthless. His daughter remembered him as a man who loved to develop something but, bored by routine, soon lost interest. Those he left responsible for decision making and day-to-day duties were not always up to the task. It remains unclear just how involved Whitney was in the stock speculation that took place, but his enterprises in Nova Scotia and New England, and their set-up, attracted others whose collective concern was minimal. A personally pleasant and genial individual, with hearing difficulties from childhood, he remained consistent in his later years, continuing to dream, to develop, and to suffer losses. He died of pneumonia at home in Brookline on 25 Jan. 1923. When the estate of “the supposed multi-millionaire,” as the New York Times had it, was probated there was surprise expressed that it was worth only $1,221.

T. W. Acheson, “The National Policy and the industrialization of the Maritimes, 1880–1910,” in Atlantic Canada after confederation; the “Acadiensis” reader: volume two, comp. P. A. Buckner and David Frank (Fredericton, 1985), 176–201. Ron Crawley, “Class conflict and the establishment of the Sydney steel industry, 1899–1904,” in The Island: new perspectives on Cape Breton’s history, 1713–1990, ed. Kenneth Donovan (Fredericton and Sydney, N.S., 1990), 145–86. W. J. A. Donald, The Canadian iron and steel industry: a study in the economic history of a protected industry (Boston, 1915). E. A. Forsey, Economic and social aspects of the Nova Scotia coal industry (Montreal, 1926). M. D. Hirsch, William C. Whitney, modern Warwick (New York, 1948; repr. [Hamden, Conn.], 1969). Kyle Jolliffe, “A saga of Gilded Age entrepreneurship in Halifax: the People’s Heat and Light Company Limited, 1893–1902,” N.S. Hist. Rev. (Halifax), 15 (1995), no.2: 10–25. T. W. Lawson, Frenzied finance (New York, 1905). Don MacGillivray, “Henry Melville Whitney comes to Cape Breton: the saga of a Gilded Age entrepreneur,” Acadiensis (Fredericton), 9 (1979–80), no.1: 44–70. National cyclopædia of American biography . . . (63v., New York, [etc.], 1892–1984), 10. N.S., House of Assembly, Debates and proc., 13 March 1892: 123–24; Journal and proc., 1893, app.16: 1–8. David Schwartzman, “Mergers in the Nova Scotia coalfields: a history of the Dominion Coal Company, 1893–1940” (phd thesis, Univ. of Calif., Berkeley, 1953).

Cite This Article

Don MacGillivray, “WHITNEY, HENRY MELVILLE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/whitney_henry_melville_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/whitney_henry_melville_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Don MacGillivray |

| Title of Article: | WHITNEY, HENRY MELVILLE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 26, 2025 |