Source: Link

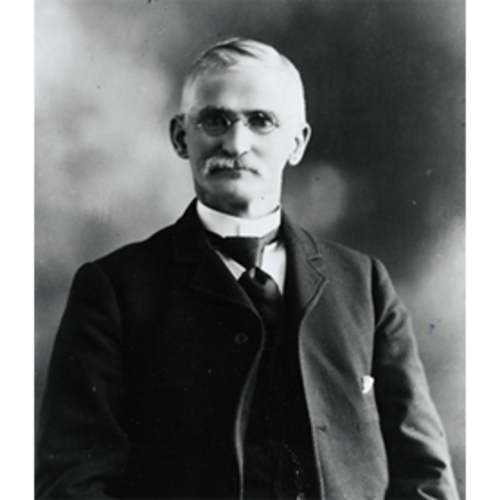

DRUMMOND, ROBERT, coalminer, trade union leader, journalist, and politician; b. 29 Oct. 1840 in Greenock, Scotland, son of Robert Drummond and Elizabeth McAllister; m. 1871 Mary (May) Douglas Alexander, and they had one daughter who died in childhood; d. 26 Dec. 1925 in Stellarton, N.S., and was buried in Springhill.

Robert Drummond was one of the most significant figures of 19th-century Canadian labour history. As grand secretary and pre-eminent spokesperson for the Provincial Workmen’s Association of Nova Scotia, a union whose membership was mainly comprised of coalminers, and later as the mining industry’s voice in the Legislative Council and in his own newspaper, Drummond played an important role in redefining industrial relations and entrenching liberalism in the eastern coalfields.

The son of a grocer, Drummond emigrated from Scotland about 1865. He found employment in the coalmine at Lingan, Cape Breton Island. On his initial visit to the mine he was taken into one of the rooms where the coal was hewn; there he encountered a worker whose misplaced lamp set off a miniature explosion. “This,” Drummond would later remember, “was the stranger’s first acquaintance with an explosive mine gas mixture.”

Nova Scotia coalmining was volatile in every sense from the 1860s to the 1890s. Alongside the venerable General Mining Association, which until 1858 had held monopoly rights on coal, could be found many new American- or central-Canadian-owned mining companies, trying to survive in a newly competitive realm, one that was also influenced by drastic shifts in international market conditions and the policies of a revenue-seeking, increasingly regulatory liberal state. In the absence of adequate safety inspection, and having no union, miners confronted physical danger, irregular work, low wages, and often high-handed bosses. Drummond, like many miners, adapted to these conditions by moving from pit to pit in search of steady work; he also unsuccessfully tried to set up a small shop on his own account. About 1872 he left Cape Breton for the coalfield in mainland Pictou County, where he found employment at the Drummond colliery in Westville; in 1873 it was to be the scene of one of North America’s most deadly mine explosions. After a brief stint as a timekeeper at another Pictou mine, he was offered a position around 1874 as the bank boss, or surface supervisor, at the rapidly expanding mine at Springhill, a flourishing new Cumberland County community whose prosperity was built on selling coal to local industrial consumers and, above all, to the Intercolonial Railway.

Born into the lower middle class, well disciplined in the habits of thought and practice of Scottish Presbyterianism, profoundly impressed by and almost monotonously eloquent about such values as thrift, self-help, and independence, Drummond was, many contemporaries would remark, a bright-eyed and materialistic Scot-on-the-make. All his adult life he spoke with a Scottish accent, peppered his talk with quotes from Burns as well as from Shakespeare and the Bible, ardently defended the values of Presbyterianism, and celebrated the triumph of science and material progress with an enthusiasm worthy of Adam Smith or Horatio Alger. In another context and, perhaps, with a less developed rebellious streak, Drummond would have been remembered, if at all, as one of a vast legion of colonials for whom liberal praxis and identification with the British homeland were two sides of the same coin, inseparable aspects of a Victorian ideology of social improvement and individual self-betterment that had all the force of a secular religion. Yet in the two overlapping phases of his public life – 1879–98 in trade unionism and 1891–1925 in the Legislative Council and in mining journalism – Drummond, operating in an unusual context and with unusual qualities of eloquence and self-confidence, challenged and transformed elements of the transatlantic liberal culture that had so deeply shaped him.

Drummond’s career as a trade unionist began in early 1879, when the Spring Hill Mining Company, after declaring large dividends in the mid 1870s and having invested £60,000 to take over territories controlled by the General Mining Association, imposed a wage reduction of three cents per box of coal cut. There followed a further three-cent reduction in August, which brought the miners out on strike. Neither wage reductions nor strikes were novelties to the industry, which had been shaken by violent clashes earlier in the decade, but the company’s tactic was singularly ill-judged in 1879, when business and coal prices were reviving and the company was conspicuously prosperous. As bank boss, Drummond was in a good position to investigate the merits of the company’s case, and he publicized the unflattering results of his inquiries under the nom de plume “A Traveller” in a Halifax newspaper. He lost his job, but gained a career in the labour movement: when he attended a clandestine miners’ meeting in Springhill, he was hailed as a hero and, on 29 Aug. 1879, he was placed on a committee to draft a constitution and by-laws for the Provincial Miners’ Association. On 1 September he became the salaried grand secretary of the new body. The union’s ensuing victory in Springhill enhanced its reputation: by the end of 1879 lodges had been organized in Stellarton, Westville, and Thorburn in Pictou County. The Trades Journal, edited by Drummond, was established in January 1880 to bring the association’s viewpoint to an even wider audience. That same year the union rebaptized itself as the Provincial Workmen’s Association, to welcome workers other than coalminers, and began to organize in Cape Breton, where it encountered fierce opposition from mine managers but ultimate acceptance as the voice of the miners.

Down to 1897 Drummond would be the storm petrel and main lobbyist of the PWA, but he was not its chief bureaucrat or leader in a 20th-century sense. He was fearless in his irreverent denunciations of managers who would not negotiate, and particularly inventive in conscripting the language of a Presbyterian and Scottish “common sense” in the struggle to show that the new union was not a criminal conspiracy but a moderate force for change within the terms of the liberal order. The association’s ritual, strongly influenced by freemasonry, probably reflected Drummond’s ingrained pragmatism and belief in self-help: prospective members were required to swear, among other things, “not to indulge in visionary theories” or to imagine that there was “a good time coming” when plenty would be easily obtained. They were also counselled that, “in taking a stand against what we consider misdirected impositions of employers, we must not ourselves be unreasonable.” “Our object is not to wage a war of labour against capital, nor to drive trade, by oppressive measures, from the locality; on the contrary, by mutual concessions between master and man, we seek to have it carried on with advantage to both.” Drummond upheld the values of a classical liberal individualism, and “None cease to rise but those who cease to climb” was both the association’s motto and his own cherished belief. They were words of improvement – the PWA would call consistently for mining schools, better training for managers, and more effective mine inspection – but they could also be, when applied to workers, and mine workers particularly, words of resistance, justifying the approximately 70 strikes mounted by the union while Drummond was its grand secretary, one of which – the 1886–87 general colliery strike in Pictou County [see Henry Skeffington Poole*] – was among the largest industrial disputes known in Victorian Canada.

However moderate and soothing its documents, the union had a more radical side: the PWA’s local records reveal hundreds of day-to-day acts of negotiation and resistance in the pits, as managers were forced to bargain with their employees. Drummond’s PWA was not a vast inclusive movement like its contemporary the Knights of Labor, but (excepting a few non-mining lodges) a small, often embattled confederation of coal workers, generally under the leadership of the colliers, the skilled workers who actually cut the coal. The union’s Grand Council, frequently a voice of moderation, was regularly contradicted by the local lodges and (until a constitutional change in 1891) by the autonomous Cape Breton subcouncil. Drummond, ever concerned to present the public with a portrait of a union that was decorous and realistic, capable of seeing both sides of demands for wage reductions and of acknowledging the principle of the managers’ authority, nonetheless did little to interfere with local lodges who fought for their members’ interests. One can often hear him, in the Trades Journal, chastising managers, bureaucrats, and politicians for failing to live up to the liberal ideal of the rational, self-contained individualism he championed. Contrary to the image subsequently painted by his critics, and by himself, Drummond was frequently the defender of strikes, even ones which involved a measure of violence against management, as the only way workers could fight for their rights under difficult local circumstances.

In a sense Drummond sanctioned, and even encouraged, the consistent application of a doctrine of liberal individualism to the coal industry – a doctrine which, because it unequivocally defended the right of independent colliers to a large degree of control over their working lives, not to mention better wages, also entailed recognition by management of the workers’ right not just to organize a union but also to prescribe a good deal of the mines’ day-to-day operations. The PWA’s more famous struggles for mine-safety legislation were linked to this conception of working-class independence: those who inspected the mines should be, in part, answerable to the miners, whose lives were at stake in the pits. Drummond was a brilliant propagandist, a master of Victorian rhetoric and fond of a broad Scottish humour; in the Trades Journal, widely read in the coal communities, including those in which it had been banned by management, he succeeded in making mine managers and servile workers look unmanly and irrational. In these diverse struggles Drummond was consistently and adamantly a radical liberal who believed that in industrial life, no less than in politics, individuals should be treated with respect and accorded power over the most important aspects of their lives. For him, it was a matter of democratic common sense that managers of coalmines, working the “people’s coal,” were public officials subject to public scrutiny. Drummond chastised them with all the subtlety of a Presbyterian elder admonishing errant members of his congregation, or (to use an epithet that was once attached to him) a furiously indignant Scottish terrier. That such a defence of workers’ collective (and at times violent) activism could coexist in a journal that routinely celebrated the mid-Victorian pieties of temperance, respectability, religion, and decorum can only be explained with reference to the radical liberalism which sustained its editor. Drummond saw no contradiction.

Three additional historical developments of great significance can be associated with Drummond as a trade unionist. First, through the PWA he contributed to the democratization of public life in Nova Scotia. Although demands for universal manhood suffrage had been made before the emergence of the PWA, the association did much to push the issue by entering provincial politics and running candidates in 1886, by petitioning the federal and provincial governments, and by pursuing the matter steadily in the Trades Journal. The extension of the franchise in 1889 to the majority of working men was in large measure Drummond’s and the PWA’s achievement. In the 1890s he would be among the most eloquent Liberal voices raised on behalf of full female enfranchisement, including women’s rights to hold public office. Second, with the support of Edwin Gilpin*, inspector of mines from 1879 and deputy commissioner of public works and mines from 1886, Drummond and the PWA pushed hard and successfully for tougher mine laws. Some concerned safety; the abolition in 1891, after a tragic explosion at Springhill [see Henry Swift*], of the use of gunpowder in gaseous mines, perhaps the PWA’s single greatest achievement, undoubtedly saved many lives. Others involved technical education for miners, the appointment of checkweighmen (officials who recorded daily coal production), the setting of a minimum age at which boys (a vital part of the 19th-century workforce) could enter the pit, and the criteria for determining when one was qualified to become a collier (in 1891 these included one year’s experience in the mine). Third, Drummond and the PWA brought about a new recognition of trade unionism as a legitimate force in social and economic life. Written collective agreements, the first signed in 1885 in Springhill, represented an important new approach to industrial relations in Canada. The country’s first compulsory arbitration legislation, passed in 1888, although it never tamed the autocracy of managers to the extent the association had hoped, made a tangible difference in Springhill, where the lodge was able to defeat a stubbornly anti-union employer by drawing not only on the arbitration law but also on the personal mediation of Premier William Stevens Fielding. The coalminers of Nova Scotia were historically among the most creative and radical workers in 20th-century Canada; it is not unrealistic to look for intimations of their dynamism and solidarity in the radical liberal era of the PWA.

In the 1890s Drummond would find himself less and less at home in the PWA, which gradually became more of an industrial union than a craft union implicitly centred on the colliers. Many in the PWA, now increasingly concentrated in a fast-developing Cape Breton, argued for legislation to end company stores and establish an eight-hour day. Drummond, however, opposed any law that prohibited workers from giving orders for supplies in company offices. It was this issue that led him to abandon the leadership of the PWA in 1898, though there had been indications of his frustration earlier in the decade, as he came to realize that he had less influence with the Fielding government than he had hoped.

Drummond’s second career, which can be dated from his appointment to the Legislative Council in 1891, distanced him from the workers whose activism he had once justified. After his removal to Stellarton in the early 1880s, he had begun to acquire middle-class respectability. A pillar of St John’s Presbyterian Church, he became prominent in local politics (he was a councillor and then mayor in 1899–1900) and the proprietor of his own paper, the business-oriented Maritime Mining Record (1898–1924). His appointment to the council had come after he had twice unsuccessfully run for a seat in the House of Assembly, first in 1886 as an independent and then in 1890 as a straightforward Liberal.

It is conventional to write of his second career in terms of unprincipled ambition and opportunism, and it is fair to suggest that by the end of his life Drummond – whose will allocated $19,000 to his kinfolk, church, and favoured charities – had prospered as a result of mining investments, business journalism, and membership in the council. Much of what Drummond said and wrote in this period predictably celebrates the achievements of far-sighted capitalists and the provincial government (although he would become progressively more critical of the latter for its timid approach to mine promotion and development). It was only in his second and last book, his memoirs as a trade union leader written shortly before his death, that he returned to his older radical liberal critique of mine managers, but even here Drummond was concerned to make his union record appear much less combative than in fact it had been.

Drummond in his later years was primarily an apologist for the coal companies. He championed the government’s 1893 deal with Henry Melville Whitney, through which the Dominion Coal Company swallowed up most of industrial Cape Breton, and he would later write glowingly of the British Empire Steel Corporation (Besco), the giant merger which had taken over much of the industry. Speaking in the Legislative Council in 1910, Drummond defended local capitalists: “Now-a-days so much is said against the capitalist that one might suppose him to be a monster, in human form, whose one object in life was to keep the noses of the workmen to the grindstone. . . . The freest, most independent men in the world to-day are the men of our Nova Scotia coal mines.” Far from robber barons, the province’s coal operators were, he maintained in a detailed if somewhat indiscreet speech the following year, mainly involved in unprofitable competitive concerns struggling to deliver dividends to their shareholders. After 1918, when the industry entered into a dramatic crisis, he argued on behalf of further mergers of the coal companies, which were justified according to the laws of industrial efficiency, social utility, and the liberal political order. Non–Nova Scotians who believed that the coal communities were impoverished were victims of labour and left-wing propaganda; even the infant mortality statistics cited by some as an indictment of capitalist oppression were interpreted differently by Drummond. Company stores were a boon to the working-class men and women who used them, and if there were any problems with company housing, Drummond wrote in 1922, they were most likely the fault of the occupiers of the houses themselves, who failed to keep them clean and tidy.

Drummond despised District 26 of the United Mine Workers of America, which had replaced the PWA as the union of the miners in 1917–18. Of all the UMWA’s critics during its long struggle for acceptance in Nova Scotia, he was the fiercest and best informed. He viewed District 26 as a fifth column of American capitalists keen to damage the local industry, or of misguided and perhaps even insane radicals conspiring with the Soviets in a strange and terrible experiment in collectivism. “What a contrast the U.M.W. is to the old P.W.A., whose executive gave no place in their proceedings to mutual recriminations,” he lamented in 1920. A “riot of extravagance” in wage settlements threatened to destabilize the entire industry; workers in pursuit of $80 overcoats and $100 suits were running away from honest labour. “Notoriety is meat and drink to a certain stamp of labour leaders,” Drummond remarked, as he ruthlessly satirized the rhetoric of the leaders of District 26. In the depths of the crisis of the 1920s [see William Davis] Drummond would dismiss “cries of poverty” with arguments that workers had forgotten the habits of “industry, sobriety and thrift” once championed by the PWA. Such vituperative polemics, and they were many, written in the last decade of his life did much to damage his long-term reputation among labour historians and in the coalmining communities of Cape Breton, and made Drummond’s very name an object of contempt for leftists. It seemed that the fearless radical liberal terrier had become a reactionary curmudgeon for whom almost anything designed by Besco was blessed.

Yet this impression, valid in some respects, misses aspects of Drummond’s second career that went beyond a simple acquiescence in the imperatives of capital. Drummond became, especially in the years before 1914, the ranking authority on the development of mines and mining in Nova Scotia. His long speeches in the Legislative Council were studded with facts and figures; his editorials and articles in the Maritime Mining Record were extensively cited, in other newspapers and by politicians on both sides of the House of Assembly. Drummond was highly knowledgeable, and his journal is an indispensable source of insider information. In 1911, defending the interests of the PWA against those of the UMWA, he was able to describe the financial health and future prospects of every coal company listed in the Report of the provincial Department of Mines. More generally, Drummond always argued that such companies were exploiting the people’s coal, not their own. Along with many “new liberal” intellectuals of his generation, who believed the state had a vital role to play in bringing order to an otherwise unstable capitalist system, Drummond defended a greatly expanded role for government in exploration for minerals and in the supervision of mines. He believed that mining fatalities would be understood only if the government undertook a much more scientific and systematic inspection of mine roofs, sides, and faces. As the foremost intellectual defender of the system evolved by Fielding and carried forward by George Henry Murray and Ernest Howard Armstrong*, in which the interests of the provincial state and the mining industry were closely correlated and which saw the coal and steel industries as the vital nuclei of provincial development, Drummond exercised a very real cultural power, down to the crisis of the system in the 1920s. When the province considered limiting hours of labour in the mines, and when the UMWA later demanded an eight-hour day inclusive of the time taken to walk to the working face, Drummond’s replies would draw extensively on the practical difficulties of any regulation of hours in a province which had far-running submarine coal deposits and which confronted not only seasonal and other fluctuations in shipping but also the competition of American and British coal in the vital St Lawrence River market.

Drummond spoke with passion and authority, whether on the need for more efficiently managed and supervised “humane institutions” (he served on and chaired this committee in the Legislative Council), against imprisonment for debt, or on behalf of temperance. He was in fact one of the most eloquent new liberals of his day, who sensed acutely the need for an expansive state to rationalize the classical liberal order. Undoubtedly the core passion of his later life was the development of the province’s coalfields. His Minerals and mining, Nova Scotia (1918) is a hymn of praise to the progress of the mining industries, a work whose boosterism is so extreme that even the events of World War I are seen as illustrations of the marvels of industrial progress. When Drummond died in 1925, the Halifax Herald was not alone in saluting an almost stereotypical industrious Scot, burning with “the unquenchable ambition of his race”; many of his radical contemporaries and successors would argue that his stubborn individualism and his entrepreneurialism were precisely what had ultimately unfitted him as a 20th-century trade-union leader. He nonetheless commanded a great deal of credibility within the state and in society generally.

Nothing was “so repulsive, so offensive, so nauseating to the workingman as to be patronized and patted on the back with the saying ‘Oh poor fellow,’” Drummond had remarked concerning a local assessment law in 1892. “What are we,” he asked in arguing against the abolition of company stores four years later, “free men, or are we cowards? Are we men, or are we weaklings?” To the end of his days Drummond would defend a radical liberal vision of working-class independence, even as its logical and social preconditions eroded around him – mainly as a result of the state-stimulated monopsonies he himself had welcomed and later praised. Since the 1920s historians of Cape Breton and of Canadian labour have routinely denounced Drummond as the opportunistic antithesis of the socialist trade unionist they admire. It could be argued that they have tended to underestimate the staying power of the profoundly liberal approach to industrial life that Drummond exemplified and which, for better or worse, many Canadian workers have historically preferred. For all his contradictions, inconsistencies, and reversals, and perhaps partly because of them, Drummond, one of Nova Scotia’s more interesting new liberal politicians, should also be remembered as a representative and revealing figure in Canadian working-class history. In 1924, when he reminisced about his trade-union career to the Mining Society of Nova Scotia, of which he had been a member – and often an executive member – since 1902, Drummond delighted in reminding his audience about the PWA’s first big strike at the Drummond colliery in 1879. The manager, in Drummond’s fond memory, was completely humbled by the association’s valiant forces. Forced to recognize the union and its representatives, he drew the line at “recognizing” the irritating, offensive figure of its grand secretary, for whom he reserved the Scottish epithet “the clatty little bugger.” It was obviously a memory, and an epithet, that 45 years later Drummond, unrevised and unrepentant, still cherished.

Robert Drummond’s publications include: To the officers and members of Keystone Lodge (Stellarton, N.S., 1896); “The mine and the farm,” Mining Soc. of Nova Scotia, Journal (Halifax), 14 (1909–10): 15–29; The sixties and subsequently; paper read August 31st, 1912 (n.p., [1912]); “Mining fatalities,” Mining Soc. of Nova Scotia, Journal, 19 (1914–15): 49–58; Minerals and mining, Nova Scotia (Stellarton, 1918); “The beginnings of trade unionism in New Glasgow,” Evening News (New Glasgow, N.S.), 7 July 1924 (reissued in Canadian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Trans. (Montreal), 20 (1924): 914–32); and Recollections and reflections of a former trades union leader ([Stellarton, 1926]).

Dalhousie Univ. Arch. (Halifax), MS-9 (Labour union papers), Provincial Workmen’s Assoc., no.27, Holdfast Lodge, Joggins, N.S., minutes. General Register Office for Scotland (Edinburgh), Greenock (West), reg. of births and baptisms, 29 Oct. 1840 (mfm. at Scottish Record Office, Edinburgh). Human Resources Development Canada Library (Hull, Que.), Provincial Workmen’s Assoc. of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, Constitution, by-laws, and minutes of proc. of the grand council, 1879–1917 (typescript). NSARM, Mining Soc. of Nova Scotia, minutes, 1902 (mfm.); RG 21. Pictou County Court of Probate (Pictou, N.S.), Estate papers, will of Robert Drummond (mfm. at NSARM). Eastern Chronicle (New Glasgow), 29 Dec. 1925. Evening News, 28 Dec. 1925. Halifax Herald, 21 Feb., 7 March 1895; 28 Dec. 1925. Trades Journal (Springhill, N.S.), 1880–82; continued at Stellarton, 1882–91. Canadian Mining Institute, Monthly Bull. (Montreal), no.[81] (January 1919)–no.98 (June 1920); continued by the Canadian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, no.99 (July 1920)–no.124 (December 1924). Eugene Forsey, Economic and social aspects of the Nova Scotia coal industry (Montreal, 1926); Trade unions in Canada, 1812–1902 (Toronto, 1982). Dawn Fraser, Echoes from labor’s wars, intro. David Frank and Donald MacGillivray (expanded ed., Wreck Cove, N.S., 1992), intro. M. S. Kirincich, A centennial history of Stellarton (Antigonish, N.S., 1990). H. A. Logan, The history of trade-union organization in Canada (Chicago, 1928). Ian McKay, “‘By wisdom, wile or war’: the Provincial Workmen’s Association and the struggle for working-class independence in Nova Scotia, 1879–97,” Labour (St John’s), 18 (1986): 13–62. Maritime Mining Record (Stellarton), 1900–24. John Moffatt, P.W.A. Grand Secretary Moffatt’s valedictory report (n.p., [1917]). N.S., House of Assembly, Debates and proc., 1906, 1910–11; Legislative Council, Debates and proc., 1891–1922. B. D. Palmer, Working-class experience: rethinking the history of Canadian labour, 1800–1991 (Toronto, 1992). David Pigot, The Mining Society of Nova Scotia, 1887–1987; a history of the society . . . (Glace Bay, N.S., 1987). Post office Greenock directory . . . (Greenock, Scot.), 1864/65. S. M. Reilly, “The Provincial Workmen’s Association of Nova Scotia, 1879–1898” (ma thesis, Dalhousie Univ., 1979). Daniel Samson, “Dependency and rural industry: Inverness, Nova Scotia, 1899–1910,” in Contested countryside: rural workers and modern society in Atlantic Canada, 1800–1950, ed. Daniel Samson (Fredericton, 1994).

Cite This Article

Ian McKay, “DRUMMOND, ROBERT (1840-1925),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/drummond_robert_1840_1925_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/drummond_robert_1840_1925_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ian McKay |

| Title of Article: | DRUMMOND, ROBERT (1840-1925) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 29, 2025 |